M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

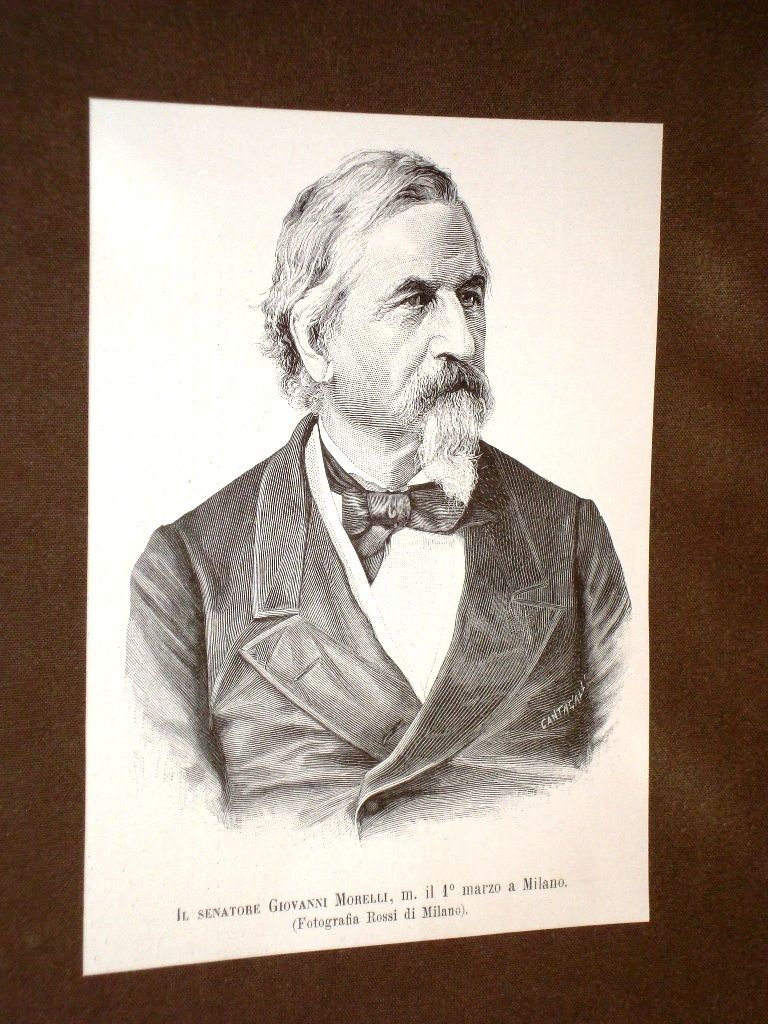

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

A Biographical Sketch in Nine Panoramatic Views  |

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH:

(1816-1826) A BIRDS’ CABINET OR:

A LA RECHERCHE OF YOUNG GIOVANNI MORELLI

(1826-1832) A SCHOOL IN SWITZERLAND

(1833-1840) APPLYING THE SURGEON’S INSTRUMENTS OR:

A YOUNG STUDENT DISCOVERS HIS LITERARY AMBITION

(AND LOSES HIS SCIENTIFIC ONE)

(1840-1847) A RIDER ON A DAPPLE GREY OR:

CRISSCROSS RIDING IN THE LOMBARDIC PRE-MARCH ERA

(1848-1849) IN THE LINES OF THE SHARPSHOOTERS

AND ON AN IMPOSSIBLE MISSION TO FRANKFURT:

MORELLI IN THE EUROPEAN REVOLUTIONS OF 1848/49

(1850-1860) IN SEEMING SECLUSION OR:

NO NEWSPAPERS ALLOWED ON THE BALBIANELLO

(1860-1870) FORGED TO PROMETHEUS’ ROCK OR:

ONE DECADE IN POLITICS

(1871-1873) IN A LAND DEAR TO ONE’S FANCYING OR:

LAST PREPARATIONS

TO BECOME A CONNOISSEUR OF ART

(1874-1891) ›MY LIFE’S FAVOURITE WORKING ACTIVITY‹ OR:

GIOVANNI MORELLI’S LATE APPEARANCE

ON THE EUROPEAN SCENE OF CONNOISSEURSHIP![]()

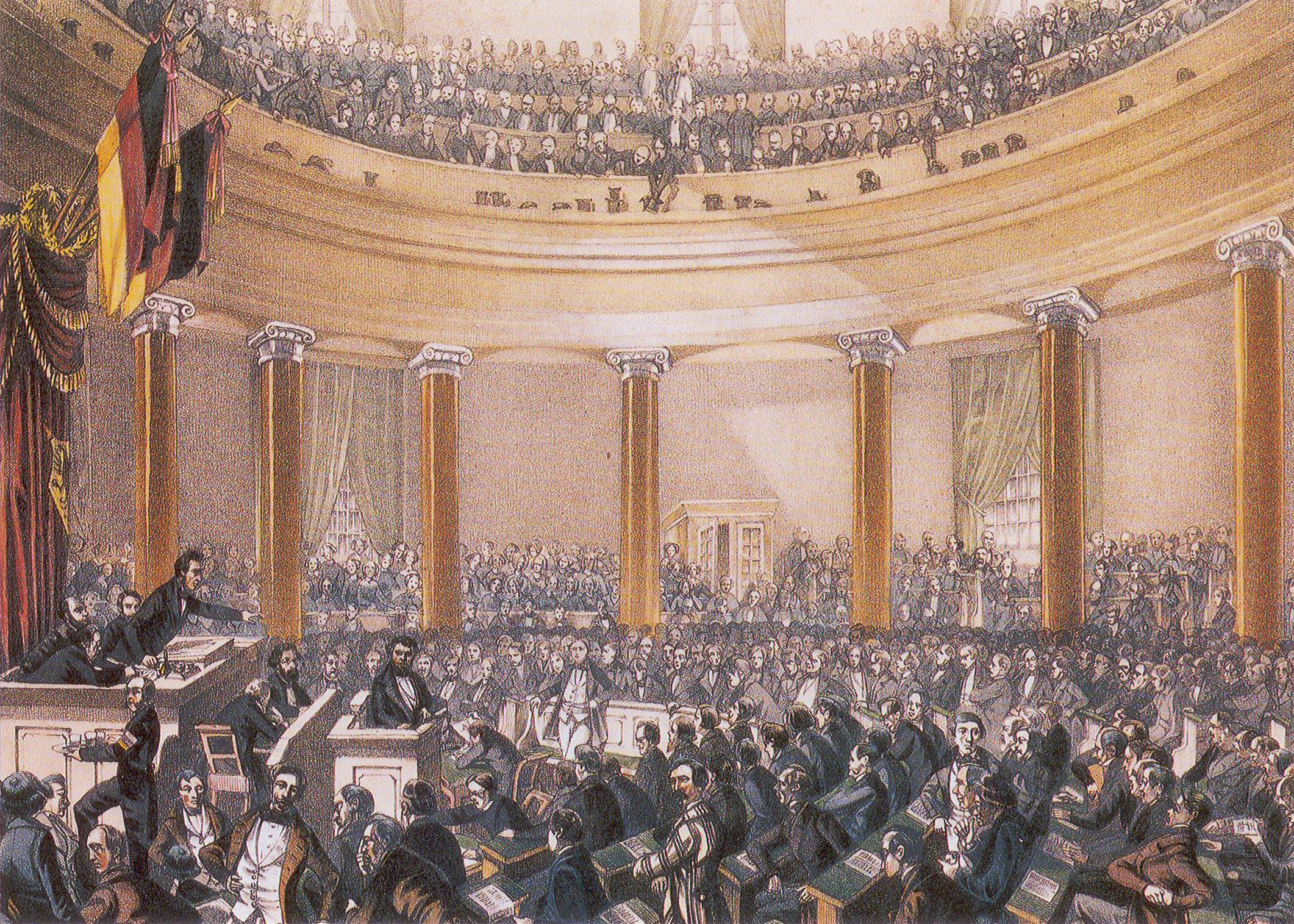

When 32-year-old Giovanni Morelli, in 1848 and as a special emissary of the Lombardic revolution, headed to the German city of Frankfurt am Main where he was meant to convince the members of the German national assembly of the legitimacy of the Lombardic uprisings against the Austrian rule, he could look back at eight years of his life that he had spent almost entirely in the one country that he regarded as his actual home, and this was Italy, more precisely: Lombardy. Writing as »ein Lombarde« (see Morelli 1848), he directed »Worte«, some words, in his unfamiliar role as a political lobbyist, to the elected representatives that were assembled at Frankfurt, coming from all parts of Germany (representatives also, some of which were still regarding Northern Italy as a part of Austria, and by that, even of Germany). His brochure, his Worte eines Lombarden an die Deutschen was written not without a furious passion, and Morelli could hardly keep back and hide diplomatically – although he pretended that he could – his anger, his rage, caused by the Austrian rule in Italy in general, and by recent events, comprising also some atrocities that he had witnessed himself, very in particular. What he could hide diplomatically, however, at least more or less, was the fact that he himself, Giovanni Morelli, was the author of these Worte eines Lombarden an die Deutschen that declared also (wrongly, as it was to turn out) that the Austrian tyranny, after 34 years, had been ended.

Yet if Morelli could more or less hide that he himself was the author of the Worte eines Lombarden an die Deutschen, he of course acted openly when being a special emissary and political lobbyist. And the mere fact that he was such an emissary might have seemed a little mysterious at least to one member of the elected German national assembly, namely to Peter Kaiser, who was not only the representative of Liechtenstein, but also had been young Giovanni Morelli’s teacher of history, and this in Switzerland, at Aarau, where young Morelli had attended school. Maybe Kaiser did also remember that Morelli, at Aarau, had been regarded, at least from the perspective of the school, as a pupil originating from Thurgau, and that, by origin, by official nationality, Morelli was actually Swiss. Not to mention that it had been Morelli’s Swiss nationality that had allowed him to study abroad, that is: at Munich, which, seen from the perspective of an Austrian bureaucrat working in Milan or Vienna, was to be considered as ›abroad‹ (and Habsburgian subjects were not allowed to study abroad).

But there was even another representative at Frankfurt am Main who knew Morelli, the cheerful and at times hilarious student at Munich, from Munich. And this was Ignaz (von) Döllinger, the younger, son of Ignaz Döllinger, the elder, the late professor of anatomy who had not only been Morelli’s teacher at Munich, but even had supervised Giovanni Morelli’s doctoral dissertation, not to mention that Döllinger, father, had been very fond of his cheerful student who – but this had been probably less obvious to Döllinger the elder – was about or already had settled inbetween the German, the Italian, and not to forget: the Swiss culture. If one was to imagine that a Habsburgian spy would have had to clarify the biography of this mysterious passionate Non-Habsburgian subject, and that is also: to disentangle the complicated identity of this mysterious Lombardic special emissary to Frankfurt, this Habsburgian spy, if not entangled himself into complicated questions of nationality and cultural identity, might have come up with a file that we are now prepared to open.

ONE) A BIRDS’ CABINET OR: A LA RECHERCHE OF YOUNG GIOVANNI MORELLI (1816-1826)

Piazza di Citadella, Verona

By an unknown artist

(source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 265)

On February 25 of 1816 this special emissary-to-be had been born in Verona, that is, in the Venetian part of the then Austrian-ruled Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia.(1) His father, who, probably, had been born at Verona as well, had died early, and had been the son of a Swiss emigrant, coming from Wöschbach at Lake Constance, where the Morell-line can be traced back to the era of the Reformation. Giovanni Morelli, or also: Johann Morell, had italianized his name actually, as our Habsburgian spy did also realize, in 1848, only recently).(2)

Morelli’s father had gained fortune and reputation originally as a merchant of silk, and the origin of a fortune that his only surviving son, his only surviving child later had at his disposition (the capital had apparently partly been invested into some manors, but Morelli inherited also capital that he could, in close cooperation with his mother, invest, on his part, into a small manor), the origin of this capital was either obvious to everyone, or, more likely, rather being camouflaged by Giovanni Morelli, who was, although his whole economic existence rested, directly or indirectly, on the economy of silk, rather eager to define himself as not being part of that economy or of the world of merchants, or as the son of a merchant (who obviously had also expanded his professional acticity, in cooperation with a partner, also being a descendent of an emigrant, to banking, and who also had been active in presiding the Verona chamber of commerce). The existence of young Giovanni Morelli had been, from the beginning, an urban one, centered at Piazza di Citadella in Verona where his parent’s house was situated,(3) but it had also been, spoken figuratively, immersed into the mulberry woods of Lombardy and the Veneto. His mother whose family originally was also from Switzerland, namely from Graubünden, was, on her part, the daughter of a producer of silk.

Giovanni Lorenzo Morelli, thus the full name of our special-emissary-to-be, was the child of a marriage in the millieu of the masters of silk, and this marriage had been contracted – in 1813 – yet in Napoleonic time. By confession, or, as Morelli himself had it, who all his life tended to freethinking: by birth Giovanni Morelli was a Protestant,(4) and Protestantism the social space he lived in, in the more narrow sense. Protestantism, within a Catholic country, was the subculture he descended from, moving, all his life, in circles of diligent ›gewerbefleissiger‹ Swiss emigrants who were residents in Austrian-ruled Northern Italy. Thus: In more than one sense Giovanni Morelli, by birth, has to be regarded, socially, as having been an outsider – namely as a foreigner, and not as a Habsburgian subject, and secondly as a Protestant within a largely Catholic country –, while on the other hand he was emotionally and culturally rooted especially in Bergamo, and his relationship with this town and with this country, was a most affectionate one. Giovanni Morelli was deeply attached to the country of his birth, which means here: to the country, its culture and its people, since there was no state, that he could be attached to equally and emotionally and intellectually identify with (and with Switzerland as a state, although Morelli would certainly legally have been entitled to, he apparently never did identify, nor culturally, nor emotionally, although he was also deeply attached to individuals who were, legally, being Swiss).

As the most incisive event of Giovanni Morelli’s childhood days certainly the early death of his father in 1820 has to be named, a loss that occured when young Giovanni was just four years old. His mother, after the event, was to settle with Giovanni, the only surviving of actually three sons, in her home town of Bergamo, and from this early striking of roots in this particular city and its surrounding landscapes Morelli’s attachment to the country and its people was to originate from (his attachment to Verona, a city that he tended to see as the symbol of Austrian rule and especially of the Austrian military whose presence was painfully obvious also at Piazza di Citadella, was certainly less profound). Impressions of how the male youth of Lombardy used to grow up in the first part of the 19th century, impressions informed by, if not penned down by Morelli himself, his fatherly friend, German professor Johann Georg Veit Engelhardt, has transmitted (in direct cooperation with Morelli) to us:

›Moving from early childhood on in free air and under many people, they do not only experience the physically strengthening effect of this life, but their eye is also drawn to the manyfolded occurrings under a free heaven; they learn to observe, and their eye is sharpened in regard to all significant, inasmuch as it is for all weakness and all ludicrousness; yet as boys they learn to bootstrap and to trust themselves, they stand more fresh and with more strength on their hips and do move with more ease in life as such. In free air one does have to talk with more strength, the gestures turn to be more lively, hence the often misinterpreted and apparently fierce gestural movements and the screaming talking of the common Italian which does attract as much attention of the foreigner.‹

························································································································································································································

»Von früher Kindheit an in freier Luft unter vielen Menschen sich bewegend, erfahren sie nicht nur den körperlich kräftigenden Einfluß dieses Lebens, ihr Auge wird auch von den mannichfachen Vorkommnissen unter freiem Himmel angezogen; sie lernen beobachten, und ihr Auge schärft sich für alles Bedeutende wie für alle Schwäche und Lächerlichkeit; sie lernen schon als Knaben sich selbst helfen und sich selbst vertrauen, sie stehen frischer und kräftiger auf ihren Hüften und bewegen sich gewandter im Leben. In freier Luft muss man stärker reden, die Gebärden werden lebendiger, daher die so oft missdeuteten und heftig erscheinenden Bewegungen und das schreiende Reden des gemeinen Italieners, das den Fremden so auffällt.«(5)

(Picture: Sailko: Sala pavoni

in the Museo della Specola, Florence)

In search of actual places of childhood we have to name, as to Verona, the fatherly house at Piazza di Citadella, in direct neighborhood to an Austrian military riding school, and even later Giovanni Morelli recalled and felt the rage, when recalling the corporal punishment of recruits, often stemming from rather poor Italian families, and having been forced into military service under Austrian command.(6)

But as to the Verona house we also have to recall one particular attraction, even known to foreigners, since various sources do speak of that attraction:(7) the ornithological cabinet that Morelli’s father, who, as an amateur, had developed skills in stuffing birds, had put together, and which could be seen in the palace-like house at Piazza di Citadella. As a child, thus, Giovanni Morelli did encounter, already in urban environment, the formal variability of nature – due to his father’s hobby, and due to his father’s manual skills in operating with animal bodies, skills that included apparently also the invention of certain new techniques of animal conservation, beside of his being a merchant, a banker, and beside of being active in chamber of commerce and its relating court. And – this was crucial to know for Giovanni Morelli as a young man – his father had been held in esteem by his fellow citizens,(8) beyond his early death that occured, probably due to an illness, in 1820.

As regards to Bergamo we have, as another crucial place of childhood, to name villa and garden of his mother’s father at Gorle near the actual city of Bergamo, and we have to imagine Giovanni Morelli as a boy, who is recalled as having been a cheerful boy by himself (cheerful as, apparently, also his mother’s nature was),(9) frolicking around in Villa Zavaritt (picture below) and its neighborhoods, and by this getting to know, from early on, also cicadas and cross spiders.

Unknown painter

(possibly Carl Adolph Mende),

Orsola Zavaritt (1795-1867),

mother of Giovanni Morelli

(source: Honegger 1997, p. 61;

and compare Bonaventura Genelli

to GM, 8 August 1844)

Villa Zavaritt at Gorle (source: Honegger 1997, p. 117)

(Picture: Ago76)

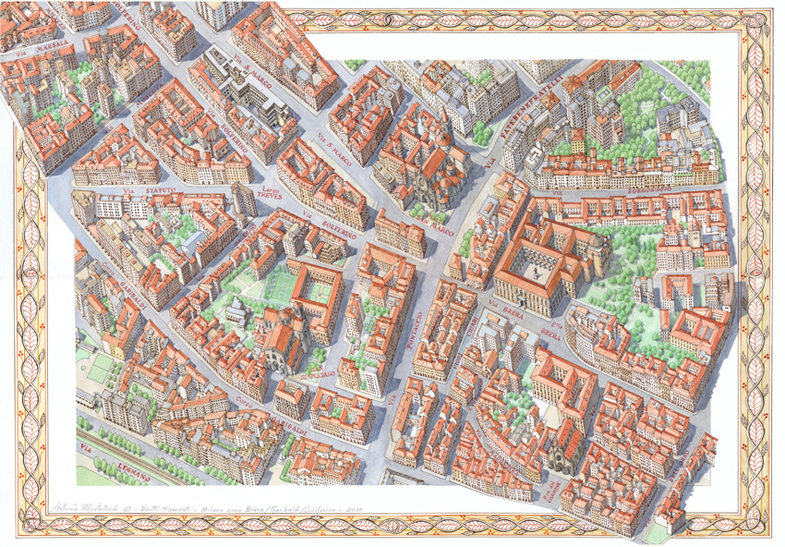

Frolicking around, as we can lively see in our mind young Giovanni Morelli, he also used to at Borgo San Leonardo, also near the actual city of Bergamo, and today being a part of the lower part of the city. At Borgo San Leonardo, very close to the actual site of the Fiera for which Bergamo was famous for, the annual coming together of the silk producers and traders. And one might imagine that young Giovanni Morelli did not only grow up at Borgo San Leonardo, but also with the annual Fiera. And the neighborhoods of Borgo San Leonardo was where Morelli found also friendships for life, namly with two of the Frizzoni brothers, with Giovanni and Federico Frizzoni, whose family did, as the Zavaritt family, belong to the Swiss colony of Bergamo, whose today-municipality is situated in the Palazzo Frizzoni.

To make friendships was a gift of which Giovanni Morelli benefitted throughout his life, and one has to imagine him as a character who was generally cheerful, who could also be passionately hilarious (and at times bullish), but who was, above all and also throughout his life, deeply attached to his friends and those relatives that he loved. Giovanni Morelli was faithful in friendship and in rivalry. And the relation to his mother remained a most profound one throughout his whole life.

If as a place of childhood we can also understand a language we have to take into consideration also that the first language of Giovanni Morelli was Italian. But he must have been familiar with German quite early in his life, since German was also (as was French as another lingua franca) spoken in the Swiss community of Bergamo. Spoken by the pastors of the Swiss colony that the colony had come from Germany or Switzerland.(10) And it might have been in this context that Giovanni Morelli was tutored for the very first time in the second, the second important (and in a certain sense, at times, the most important) language, which his mother did probably understand, but, as Morelli mentioned once, not speak.(11) And as the second incisive moment in Giovanni Morelli’s childhood we have to regard the moment when, among relatives probably, it was decided to send young Giovanni Morelli to school in Switzerland, where he did apparently arrive rather early, namely when he was ten years old, to attend school, not at Yverdon, where two uncles of Morelli had had attended the institute of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, but at the city of Aarau, in a completely different cultural environment, where Morelli was probably to attend the Sekundarschule first, to enter the well-known Kantonsschule subsequently.(12)

*

(Picture: Voyager)

TWO) A SCHOOL IN SWITZERLAND (1826-1832)

(Picture: ag.ch)

If Giovanni went to Switzerland and turned to Johann – knowing Morelli’s character one might suppose that he did so rather unwillingly, but in fact we do know rather little about young Giovanni Morelli’s years in Switzerland. But enough to imagine him living his new life.

The so-called Amtshaus (picture above) in the so-called Laurenzenvorstadt was his school. Maybe not his first school, but the Amtshaus (compare also the small period picture on the left) had been the then-building of the Kantonsschule (and houses today the Kantonspolizei). On narrow trails one might have strolled down to the Rhine, when school was out (and if one was allowed to do so), to go on for a further stroll on a »Philosophenweg«, and under, for example, a milky February sun.

Wherever Giovanni Morelli went to live – he was capable, and this we know, this was his gift – to make friendships, to attach to people, to endear people for him, to live his life, even if he – again, we do only assume – would have preferred to go on living among his Bergamo friends.

Now he was without any doubt expected to speak German, and maybe even Swiss dialect, and this having to settle within a new cultural environment meant the first such move, the first such experience in his life. It was not to remain the last.

Morelli, in later life, has remained rather silent as to his Swiss period. Only occasionally, and rather negatively, he does refer to Switzerland and to the Swiss at all (referring to them, in its typical generally dismissive way, as ›people of mongers‹, of »Krämervolk«).(13) And it was certainly not because he would not have taken something with him from his Swiss period. In truth he did so, and he did even take so many things with him that it is all the more interesting to take a closer look at these years.

Coming back to his Swiss period obviously meant something difficult for Morelli, since the core of his identity was touched on and even in question existentially. He felt being Italian, and he had, if only later in life, to make choices of whom he wanted to be, and where. And one possibility was to define himself as being Swiss, and as belonging to the Swiss culture (as his ancestors).

His later choice, though, was a different one. He did decide not only not to define himself as being Swiss (and rather to remain silent as to his Swiss descent and cultural upbringing in Aarau), he did also find his cultural points of reference, namely also his opponents, mainly in the German culture, also in the Italian, but not in the Swiss one.

And this made also a difference, beside his choice of wanting to be an Italian, respected and loved by his fellow Italians. He did refer rather reluctantly to Swiss writers, art historians, and namely to Jacob Burckhardt (we will come to that), although he did respect them. As he, one might add, respected, and even loved his Aarau teachers. Or at least some of them.

Abraham Emanuel Fröhlich (1796-1865)

18-year-old Giovanni Morelli in 1834,

as seen by Wilhelm von Kaulbach

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 70)

We have to name his teacher of German (and also Religious instruction), Abraham Emanuel Fröhlich (1796-1865), who was also a writer of fables and other literary products, and to whose nature Morelli himself referred to as ›edelstolz‹ (which might translate as ›nobly being proud‹ or: ›proud of being noble‹). Fröhlich was also a friend of Swiss writer Jeremias Gotthelf, and it was Gotthelf who can be summoned as a witness that Fröhlich also represented an example of remarkable, indeed extreme stubbornness (and the material that Gotthelf referred to, figuratively speaking, was granite, and what he meant was that Fröhlich’s head could conveniently be used to grind up granite).(14)

Fröhlich demanded that his pupils did learn poems by heart, and also did inspire his pupils to own literary experiments as for example descriptions. And it was Fröhlich who made known to Morelli those Biblical passages that he would later refer to as the most wonderful descriptions of all: the so-called speeches of the Lord from the whirlwind from the Book of Job (Job 38-42). Namely and very characteristically Morelli was most enthusiastic as to the description of the war horse (39, 19-25).(15)

His teacher in natural history was Johann Rudolf Meyer (1791-1833), also remembered as an alpinist, and it was certainly also Meyer who was capable to arouse or to enhance interest for natural history in Morelli, since we know of Meyer’s book Die Geister der Natur as an item within the art connoisseur’s later own library. With Morelli’s bequest also this book later was given to the city of Bergamo’s library.(16)

But it was probably Fröhlich, who, caused by the political stirs of the 1830s, turned to be a conservative, whose personality indeed did impress young Giovanni Morelli. And we know that, after his time at Aarau was over – Morelli left the school in summer of 1832 –, the cheerful teenager kept on to stay in contact with Fröhlich, and even wished to support him, since Fröhlich had been dismissed from the school for probably (or also) political reasons.(17)

In 1836, and to Morelli’s shock, Fröhlich’s brother Theodor (1803-1836), a composer, who had also taught music at Morelli’s school, but lived an unhappy life, committed suicide by drowning himself in the Aare. Morelli, in a letter, referred to him as ›friend‹.(18)

What Morelli certainly had in common with his teacher of German and Religious Education at Aarau was a certain conservative stance, and Morelli never turned to be a liberal, on the contrary. And if not being directly influenced by his teacher at school, one might still imagine Morelli being at least impressed by Fröhlich’s personality and stance, and to have, with Fröhlich, an example.

One of his teacher’s fables, by the way, is entitled Kennermienen (›The Expert’s Airs‹). And it is rather typical for Morelli, if he remained silent as to influences that rather directly might have affected him. Like for example the example given by his teacher, and namely also the stance that shows and expresses in this very fable:

»Affen, denen, zu erfreuen, / selber noch kein Ton gelang, / kritisieren und verschreien / jeden noch so schönen Sang, / ›Wir sind, sagen sie, nicht Dichter, / aber kunstgelehrte Richter; / uns gelingen breit und lang / alle kritischen Gesichter.‹«

·························································································································································································································

›Apes decrying joyful singing, / even any most delightful tune, / and only overly wise crooning, / we have heard from them so far, / ›Poets we are not, they say, / but called to quibbling excerpts / to excell, if not in art, / in any airs of experts.‹‹ [free translation: DS](19)

19-year-old Morelli in 1835,

as seen by Carl Adolph Mende

(source: Giovanni Morelli 1987, p. 77)

Morelli, at Aarau, was also instructed of how to draw: by the Lucerne-born Kaspar Belliger (1790-1845), and Morelli was in the habit to join those group of pupils which were trying to draw heads and figures, and not the one trying to draw flowers. But, apparently, the connoisseur of art-to-be did not exactly outstand; nor did he in History, and especially not in Swiss History: we do not find him ranking among the first, to put it mildly. Which we do as to Morelli’s being able to win prizes in Latin and Zoology.(20)

Worth noticing is also that Morelli, the later senator of the Kingdom of Italy, might have been among those Aarau pupils that helped, in April of 1832, with the organization of the first Eidgenössisches Turnerfest,(21) but we do not know of this for sure. At any rate Morelli did like, and this also later in life, physical exercises; and some of his friends, with a mix of admiration and horror, recalled walks with Morelli that had turned into several hours-long excursions.(22)

One of Morelli’s best friends in life, the Florentine Niccolò Antinori, was, at least on occasion of a longer stay with Morelli at Lake Como, probably someone to experience what physical education meant for Morelli (and what it meanat to exercise with Morelli).(23) And one might also be inclined to see here again the relation to the Aarau period, and to what Giovanni Morelli did learn also at Aarau, and also for life, although Morelli’s physical vitality does stand in contrast to several bodily ailments that afflicted Morelli throughout his life, namely mysterious pains, to be located obviously only with difficulty, that turned up periodically, especially in times of psychic tension.(24)

At Aarau one was in the habit to ring the bells, the so-called »Uselütete« did mark the departure of pupils from the school, among the sound of bells ringing.(25) If Johann Morell ever did experience this custom, we, again, do not know for certain. He did leave the school, not at the end of the actual term, but in summer of 1832, and it seems that he did not stay for the full four actually regular terms. At any rate he turned back to Bergamo, and it was the year when also his grandfather on his motherly side, Ambrogio Zavaritt, did die.

As to Giovanni Morelli’s own life we see, with his return from Switzerland to Bergamo, a pattern that was to repeat now several times. Coming back to Lombardy, to Italy, he was to depart anew, and now to another German country, namely to Germany, to Munich, where he, at the university, was to study medicine. Maybe already in fall of 1832, to start with the regular undergraduate programme, and appearing, in the regular lists of students, with the winter term of 1833/34.(26)

21-year-old Giovanni Morelli as seen

by Bonaventura Genelli in 1837

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 114)

Morelli, as a student in Munich, smoking while working his study… (source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 266)

…in third floor of Herzogspitalstrasse 9 (picture: AHert;

the house, built in the early 19th century, still being in existence)

THREE) APPLYING THE SURGEON’S INSTRUMENTS OR: A YOUNG STUDENT DISCOVERS HIS LITERARY AMBITION (AND LOSES HIS SCIENTIFIC ONE) (1833-1840)

According to a tradition Morelli’s studenthood began with a minor bombshell, that is: with a severe duel affair. Allegedly due to this mysterious affair he had to appear before the university of Munich’s principal Ignaz Döllinger, who subsequently took Morelli under his wings.(27)

Only that, while in fact Döllinger indeed took Morelli under his wings, there was no principal Döllinger at the beginning of Morelli’s studenthood.

There was a principal Johann Nepomuk Ringseis (1785-1880), whom Morelli was to know also (he was to caricature Ringseis in one of his satirical writings); and several years later, as also again much later, there was a principal Ignaz Döllinger the younger, son of the professor who did take Morelli under his wings.(28)

And since there is apparently only some truth in that tradition, we may be cautious as to believing that there was actually a duel affair at the beginning at Morelli’s studenthood. The only such affair of which we know of, more the idea of such an affair, occured much later, that is: more at the end of Morelli’s studenthood. It had to do with the Catholic culture as also represented by Ringseis. And we will come to that.

If one thing is for sure, it is that Morelli, the cheerful, hilarious, emotional and exuberantly passionate young student knew also in Munich, as in fact everywhere, to charm people. Due to his charming nature, his exuberance, and not the least: also due to his intelligence. Attached to people, he could also make people laugh, and the depicting of a severe duel affair, more symbolically, also does depict the irascible side of passionate Morelli. But, as we assume: also his distinctively waggish sense of humour. Because throughout his life Giovanni Morelli liked to make up, to invent, to rewrite actual events, and he delighted if people were to believe the products of his waggish humour (more examples are to come).

Ignaz Döllinger, the elder Döllinger, became his mentor. But Morelli, the curious young man, socialized with Catholic and with Protestant circles. Namely the Protestant circle, grouped around Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert (1780-1860), the author of the famous ›Views from the Night Side of the Natural Science‹ (Ansichten von der Nachtseite der Naturwissenschaft) of 1808, and the philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775-1854); and the Catholic circle around publicist and historian Joseph Görres (1776-1848). Not to forget poet and writer Clemens Brentano, whom Morelli paid many visits; and artist circles in general.

In brief: Morelli began on the one hand to study very seriously, and at the same time he began to discover, also with his own joy of discovery, a cultural scene, a city, human nature and the world as such.(29)

And it was literature that became his passion, his probably greatest passion at the time. Which meant not only reading and a devouring of an impressive amount of books, but also writing.

He did finish his studies in a formal way. With a doctoral dissertation.(30) And according to the common practice, a young man, willing to become a practical doctor, was now expected to turn to the practice for two years.(31) But it might have been earlier that Morelli had yet decided to follow a path into the theoretical field of the natural sciences, namely into the field of comparative anatomy, which, at the time, meant the study of human anatomy as well as the anatomy of animals.

His actual and even more important detour from a conventional career, however, was yet to more and more develop into becoming a writer.

He began, in 1836, with the spirited portrait of his own lunch club at Munich, which he had joined two years earlier. And in shape of a fictional discussion of a newly found work of art, he did not only portrait, in an fresh and original way, his fellow members of that club, but also himself. And in passing by, one might also say, he made a mockery of art historical analysis of content, describing, superficially, an Etruscan picture, but at the same time making this description transparent, in that it opened a view upon a hilarious group portrait.(32)

It was this early elaborate that made also Munich-based artist Bonaventura Genelli curious as to who the author of this original booklet, named Balvi magnus, was; and this booklet, thus, inspired also the deep friendship between Giovanni Morelli, then Johann Morell, and the Berlin-born Genelli, who, in discussing the Don Quixote by Cervantes, hit it off with each other and remained friends for life, although circumstances of living were too different later, to actually cherish the friendship apart from exchanging letters, largely unpublished letters that are, in being warm-hearted and spirited, the authentic monument to this friendship.(33)

Don Quixote as seen by Genelli, and presented to Morelli as a gift. The dedication

»A Morelli B. Genelli« is the earliest source as to an italianized form of Morelli’s name.

– When Morelli thanked his friend by letter for the gift, he also held out the prospect

to give a reading of the drawing, to have Genelli, whom he regarded as his mentor,

correct him in case he was ›wrong‹ (compare for the reading chapter

Visual Apprenticeship II; and see GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 16 February 1838)

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 115)

Another and somewhat longer satirical booklet Morelli was to publish after the Balvi Magnus: the Miasma diabolicum in 1839. And having left Munich he yet looked back upon his Munich years, and did portrait the Catholic and Protestant circles that he had been associated with.(34)

And he did also draw his inspiration from having been involved into the medical sections of the first victims of the cholera at Munich, sections that had been performed partly by his mentor Iganz Döllinger, who thereby also had become infected himself.(35) Morelli, again using a double perspective, did render a fanatical sect taking absurd, but very scholarly conducted precautions against an evil miasm, and did also study the miasm itself, using the scientific equipment of the day, like for example the modern microscope.(36)

After having passed his doctoral exam, Morelli had stayed in Munich to assist his mentor Döllinger for some time, but in the winter of 1837/38 had turned to Erlangen, where, as we already have mentioned, the bonds of friendship with professor Johann Georg Veit Engelhardt originated. Erlangen meant, for Morelli, also to socialize with another poet, namely Friedrich Rückert, who was charmed by Morelli as most people were charmed.(37)

Travelling to various places, travelling also to Berlin in 1838, Morelli found himself in Switzerland again, when joining, in the summer of 1838, an excursion, guided by the famous geologist Louis Agassiz, to the Mont Blanc glacier.(38)

But this remained another episode within the very turbulent year of 1838 that finally brought Morelli to Paris where he settled for more than a year.(39)

Continuing, with less and less passion and energy, his studies in the field of comparative anatomy. But more and more becoming immersed into the cultural and particularly literary life. And not to forget: finishing new satirical pieces, and also his – also already mentioned – comedy: entitled Kunstkenner, which dealt with the foolish scenery of art connoisseurship of the day (and of course we will come back to this particular work later).

It was in Paris that Morelli also digested what he had experienced in Munich, and recently particularly also in Berlin, where he had socialized with writer Bettina von Arnim, whom he had known to charm tremendously.(40) Bonaventura Genelli in Munich awaited, with impatience, every new letter by Morelli, that was to unfold another panorama of burlesque and also quixotic adventures.

In Paris Morelli went to the opera, the theatres, the Louvre, the circus, and he witnessed the becoming immensely popular of the new invention: the daguerreotype.(41)

A sort of ending of his studenthood brought a visit from Munich, where apparently no one was informed, that Morelli was, although he had joined also Catholic circles, not at all inclined to become a standard bearer of Catholic propaganda of the day (since at Munich, he was though to be an Italian, one simply had assumed that he was Catholic).

And Guido Görres (1805-1852), the son of the before mentioned Joseph Görres, almost had to face a duel with enraged Morelli, who was calmed down by a German named Otto Mündler, who shared an apartment with Morelli close to the Jardin de Plantes, and later, during the 1850s, was to become his mentor in becoming a connoisseur of art. The details of the almost-duel-affair Genelli was also to hear about, and we’ll come back also later to this episode.

Guido Görres (1805-1852)

Morelli, at Paris in 1839, where he also did pay visit to the Salon of 1839,(42) lived in close neigborhood to connoisseurs, but was far from wanting to become himself a connoisseur of art. What exactly he wanted he probably did not know then precisely. Or he felt that he wanted to become a writer, while he was, more and more, neglecting science. And now the time was near that he was meant to return to Italy, after having studied for several years. Resulting with finding many passions, but not exactly with having found an idea of his future career.

He spreaded his wings, in early 1840, and via Marseille and Genoa returned home.(43) Bringing home a doctoral degree, and many rather secret plans and wishes, leaving German speaking countries behind, which also meant: now having to settle anew in Italian speaking lands, that is the country of his early youth, Lombardy. And now: with his joy of discovery, he actually yet was to discover Italy and see it, if one likes so, also with German eyes and through his German Bildung. Because, in poet Friedrich Rückert’s words: he was ›an Italian by birth, a Swiss by education and a German by disposition and mind‹.(44)

FOUR) A RIDER ON A DAPPLE GREY OR: CRISSCROSS RIDING IN THE LOMBARDIC PRE-MARCH ERA (1840-1847)

Paesaggio con alberi e cavaliere by Claes van Beresteyn,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

After Morelli’s actual studenthood had ended, Morelli actually declined to end his studenthood.

In the late summer of 1840 Genelli had heard that his young friend had left his studies be studies; in 1844 it was explained to him by a scholar who knew Morelli from Paris, why (apparently due to the patience and endurance required in comparative anatomy); in early 1846 Genelli was informed that Morelli was still undecided about his actual profession (although he wished to be a playwright); and in the summer of 1845 Morelli had, probably from his heritage, bought a small manor for himself; with the result that, in early 1848, it appeared to Genelli that Morelli had become a lord of a small manor, gardening and having things organized. When the European political scene was about to explode.

Morelli indeed was turning, during the 1840s, from being a student into a man of letters and, to Genelli’s occasional puzzlement, a man of leisure.(45)

On the surface this might have appeared as being a fluent transition. But in truth there was one bigger task that may easily be overlooked: Morelli had to get acquainted with Italy anew and to settle in Italy, after having been, as Genelli had put it, to some degree ›alienated‹ from Italy.(46)

Which meant that he explored the country at first, namely Northern Italy, Florence, Venice and other bigger cities, to finally arrive in the Eternal City, Rome, in 1842. And a giro d’Italia with painter Carl Adolph Mende, another friend from Munich days, was to follow in 1843 as well.(47)

But on another level what happened, happened much less fluent, much less easy than it might appear on first sight.

Certainly: one was to refer to Morelli as being »italiano d’animo e tedesco di studii« in the following,(48) and one may say that this rhetorical formula did replace the above quoted formula coined by German poet Friedrich Rückert (who probably was one of the men in Europe and in the whole world who knew most about passages from one language into another, that is: about translation and about cultural transfer).

But it was the Florentine nobleman Gino Capponi, who was to become another mentor of Morelli and a fatherly friend, and it was Capponi who also referred to Morelli more colloquially as being ›half German‹.(49)

And beside the obvious that Morelli had now to write in Italian if he wanted to settle as a writer, German Bildung was not necessarily, not in every circle something demanded, something welcome, nor was it something that allowed that Morelli was easily understood.(50) As someone displaying, representing German Bildung in an Italian context.

But the Florentine circle of Gino Capponi indeed, to him, meant a new home.

Here it was that Morelli found friends that did understand him, here he found his most intimate friend in youth, the Florentine Niccolò Antinori, and here he found literary friends who demanded something which indeed he could do: translating assorted German writers (Goethe/Eckermann, Schelling, Schleiermacher) into Italian, and by doing that: transmitting German Bildung.(51)

And this he did, if apparently not very regularly, or showing real endurance.

Other interests distracted him, although just one new interest: politics, had also much to do or even was the outcome of his associating now with man of letters. With playwright Giovanni Battista Niccolini very in particular, who was to write the one play that Morelli felt, for some years, most enthusiastic about: the Arnaldo da Brescia. And above all: Morelli also wanted to develop as a writer. And he made, apparently introduced by Capponi, also the acquaintance of the one most prominent Italian writer of the day: namely Alessandro Manzoni (for details and sources see chapter Visual Apprenticeship I).

Giovanni Battista Niccolini (1792-1861)

Alessandro Manzoni (1785-1873), painted in 1841 by Francesco Hayez

But on the other hand: it seems to have frustrated Morelli also to some degree that namely Manzoni was that much concerned with the problem of language. That is: with the unification of Italy on a level of language.

While Morelli simply had other interests, and tended also to be a federalist in terms of language: someone who did just appreciate the diversity of various languages, including the Bergamasque idiom, and this very in particular.(52)

Niccolò Antinori (1817-1882), as rendered by Giuseppe Bezzuoli in 1834

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 102; detail)

The 1840s show Morelli – which is a fascinating sight – discovering Italy, cultural landscapes as well as the natural scenery, with the eyes of a German man of letters, with the eyes of someone being capable to draw on various traditions, the Weimarer Klassik as well as the Romantik, and the Vormärz; and at the same time with the eyes of someone wanting to settle in that country. But still did not know exactly how, and with doing what exactly.

Probably also to the surprise of his relatives, he was to give up, or actually already had given up his scientific studies. Which also meant: the result of him having been a student of medicine for many years had not only not been him becoming a practical doctor –, but he had also given up the scientific study of comparative anatomy altogether (which had been more the mimicry, as one may say, of his existence as a poet-to-be: a mask that was about to be dropped).

And if this reads, again, as something reminding rather of a comedy, in truth this all had a comical side in it, but not only a comical side.

It made Morelli probably laugh that Genelli, by letter, warned him of certain individuals coming from Munich to pay him a visit at Bergamo, individuals keen to win money from Morelli by playing cards with him (if fact these individuals Morelli knew only too well, since they had been members of his beloved Munich lunch club, and caricatures of members of that club playing cards have also remained extant).(53)

But when Morelli did return from his studenthood to Bergamo, he yet was entitled to call himself a doctor due to his dissertation thesis, but one of his uncles, Zaccaria Zavaritt, lay dying then, and it is not known if Morelli was expected to be of practical help as best as he could, or if his relatives actually knew and had understood that he was far from being a medical doctor, far from having chosen something practical as his profession, far from, as one may also add, being a connoisseur of art or something only remotely reminding of this, if to be a connoisseur of art is to be regarded as being a practical profession at all.

His uncle did in fact die, a cousin suffered of depressions, and Morelli actually did try to be of help as best as he could (and throughout his life he did so, being of assistance of those suffering, trying particularly to cheer those suffering up by entertaining them.(54)

And it was his obvious and often helpful flexibility that at the same time was at the origin of his being attracted to many things now, and not at all to one: to travelling, to reading and writing, to discussing of politics, to meeting people and to explore the country on every imaginable level.

With the result of a colorful, if somewhat torn and distracted decade, being the result of Morelli having actually not to decide what to do, since his mother did also support his way of living.

And with the result that what was to happen in the following was not at all the outcome of actual reflected decisions.

Such decisions Morelli was to spare or to avoid actually throughout his life. And the final picture of him being a gardener and farmer, of him having become a landlord(55) is a delusive picture, as many a picture from Morelli’s biography is a delusive picture: because there was more. Behind and in that picture: conflict of identity, unrest, melancholy (in 1840 he obviously, but apparently unhappily, had fallen in love with a woman)(56) and searching. Until the 1848 uprisings demanded, or seemed to demand finally: acting. On various occasions, on various stages. Improvised actions, improvised acting, reflected actions, reflected acting. And acts, at least partly, that only someone with a German Bildung was able to perform.

In 1841, when Morelli,

accompanying Gino Capponi,

again stayed in Munich,

albeit only briefly,

he was to see philosopher

Friedrich Schelling again,

who, at that time, was about

to leave for Berlin

The figure of Arnold of Brescia inspired the political thinking of the pre-revolutionary era:

a 12th century figure between the German emperor on the one hand and the papacy on the other,

and a medium to imagine the putative unification of Italy in various scenarios, involving the two superior powers

and an unconventional thinker of whose historical profile we actually do not know that much at all (picture: bresciavintage.it)

*

FIVE) IN THE LINES OF THE SHARPSHOOTERS AND ON AN IMPOSSIBLE MISSION TO FRANKFURT: MORELLI IN THE EUROPEAN REVOLUTIONS OF 1848/49

After having lived through the two revolutionary years of 1848 and 1849 Morelli did hold out to his friend Genelli to write a comprehensive report as to what he had experienced during these two years, which, according to Gustavo Frizzoni, had meant a shakening of his nature.(57)

And Morelli in fact did write this report, only that, unfortunately, it is not extant.

How might he have begun? Starting off at what point?

And how might he have structured his report? Sticking to a chronological sequence of events? Or was his mind, flexible as it was and as it was used to, turning from one digression to another, rendering episodes, and even anecdotes?

Because we do dispose of letters by Morelli from this period, and these letters, among other things, show him also remaining interested in further developing as a writer, in that he was gathering subject matters, satirized people, and reflected, yet at a time when developments were still in motion, about the possible outcome of things (for details and references see chapter Visual Apprenticeship I).

It does make sense to think of these two years as a chronological sequence of events and as a continuous accumulating of experience. But it also does make sense to emphasize a particular pattern that shows within that sequence, albeit not at first sight.

Since these two years were on the one hand indeed full of events, but on the other also left Morelli with many possibilities, with many pauses to reflect. In-between the events, and even forced by the events to reflect, as for example, as we will see, in Frankfurt.

These two revolutionary years thus show him torn between action and reflection, not torn between remaining an observer and being a participant, since he was willing to be both. Although yet within the course of these two years, he more and more was to become a mere observer, more and more sceptical as to the outcome of things, and thus, naturally, also more and more sceptical as to actually participating.

If Giovanni Morelli was already preparing for action in the spring of 1848, we do not know. It appeared to both Genelli and Capponi that Morelli was living in seclusion in his manor at Lago Pusiano; and a friend, painter Carl Adolph Mende, was with him.(58)

What seemed to be an idyll of a painter and a man of letters living a quiet life, might nonetheless be a delusive picture. Since Morelli certainly did observe the signs of the times, and the Five Days of Milan, that followed shortly after the outbreak of revolution in Vienna, one may not have expected as such; but various events, such as the Milan riots following the so-called ›tobacco strike‹ (›Zigarrenrummel‹) in early January, had been a prelude and shown that the atmosphere was indeed explosive.(59) In a word: If Mende was hunting ducks on Lago Pusiano, one might also think of him as a soldier in peace time, preparing for war. And Mende was indeed with Morelli, with Morelli who joined the Lombardic uprising, and thus a painter was with Morelli while joining the uprisings.

Morelli was to keep a rather positive view of the military in later years,(60) but we do not know exactly what he experienced while joining the military: that is, while joining and apparently leading a group of volunteers to support the Milan uprising, known as the Five Days of Milan.

This group got to the city of Milan via Monza, where a casern was taken, and subsequently put pressure on one gate of Milan, the Porta Comasina (now Porta Garibaldi), while the Austrian troups, led by Radetzky, were already preparing their withdrawal from the city. And Morelli certainly did experience the enthusiasm after the Five Days.(61)

The next act, after a first pause, and after he had been picked by the Provisional Government, was his Frankfurt mission as a political lobbyist or diplomat. Entrusted with the task to better explain the Lombardic events to the German public, and particularly to the political public of the German National Assembly. Which meant also that he was meant to counter the representation of events by the most important newspaper, the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung.

Due to the circumstances, the comeback of the Austrian troops, the victory perhaps bargained away in the summer, this mission was destined to fail, although Morelli had been committed to the task of supporting his home country with all the verve he was capable of. And since he chose to write a brochure, his Worte eines Lombarden an die Deutschen (Morelli 1848), he articulated a Lombardic view. And while articulating this view, he had to rethink what already had happened, including the events he had been a part of himself. And the brochure thus can be read as the articulation of an quasi-official position, but also as a very personal testimony of someone who had lived through the events he was describing, explaining, interpreting and – extrapolating into the future.

A short trip, probably also in diplomatic mission, but a trip that obviously had also to do with the providing of guns for the Lombardic forces, brought Morelli to Paris in the summer; and here, for example, he was also, as already in Frankfurt, to gather subjects matters for his later-to-be-written political comedies, probably in moments he also spent waiting for diplomats and politicians.(62)

The third act, after Austrian troops had regained territory and there was not point in the Frankfurt mission anymore, because one already could foresee the failure of the Lombardic revolution, showed Morelli turning to Venice, to be of help in the defending of the Republic of San Marco. Not involved in any fightings, apparently, that were to occur only later, he yet left Venice, for mysterious reasons, again in the spring of 1849. Perhaps entrusted with a diplomatic mission again, but perhaps also frustrated with the organization of defence and the political struggles within the Republic. He turned, probably after having spent again much time with waiting and perhaps also reflecting, to Genoa, and he seems to have spent time there, also being an observer. Until, apparently, he did join Piedmontese troups, heading to Novara, where the First Italian War of Independence, indeed, did come to an end, with the defeat of Novara, with Morelli arriving on the scene, as one single source (Lady Eastlake) has it, just on the eve of the Battle of Novara.(63)

In the following he headed, again after waiting, to Saint Moritz, for health reasons, and returned home. Where he probably got to know that his friend Giovanni Frizzoni was staying in Milan, due to an eye operation. And Morelli, arriving at Milan, had to face the fact that his best, his most admired friend had just died, after he had become infected with typhus after the actually successful operation.(64)

Giovanni Frizzoni (1805-1849)

(source: Honegger 1997, p. 87)

How may Morelli’s report to Genelli have ended? What might have been his then resumé?

If he had accumulated precious experiences during two extraordinary years, full of events, but also with many pauses to reflect, there was the failure of the Lombardic revolution and of the First War of Independence as such. With subsequent burdens, economic burdens, taxes (or a forced loan), imposed by the Austrian rule, particularly on the possessing classes, to which Morelli did belong.(65) And there was the loss of Giovanni Frizzoni that now added to this misery. A loss beyond measure.

Gustavo Frizzoni, son of Giovanni and then age nine, was, as said, later to write that the two years had meant a shakening of Morelli’s nature. And he was to write this, not the least, because Morelli in some sense did replace, as best as he could, Gustavo’s father. In that he became a fatherly friend and mentor to Gustavo Frizzoni, who was also to become a pupil of Morelli, and a companion.

But this was a future development that, at the time Morelli wrote his report to Genelli, no one could foresee.

As to his outward existence nothing seemed to have much changed in early 1850. We find Morelli reading, writing letters, in tone not very different from the letters that he did write before or afterwards.(66) But the two years must have meant a dramatic incision, albeit that seeds of future developments, in hindsight, can also be identified. Subject materials that Morelli was to develop into comedies, a verve that was to be invested into new political initiatives, an inclination to active life as well as to contemplation, and future friendships that had to do with the tragic loss of one friend.

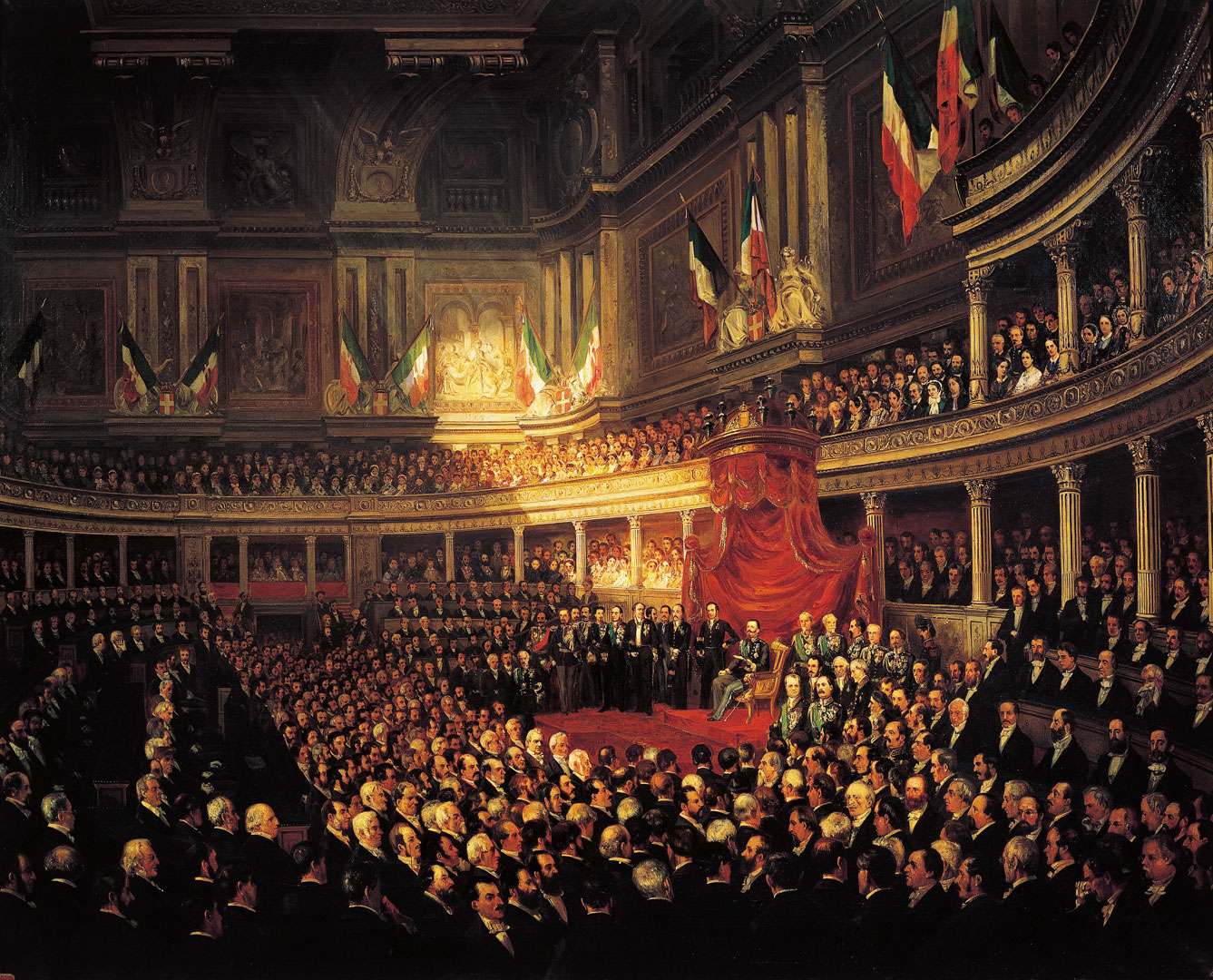

Ludwig von Elliott, Sitzung der Nationalversammlung im Juni 1848

*

According to Giovanni Morelli no newspapers were allowed on the Balbianello, that is: in the Villa Balbianello, when, in 1851, he stayed at this enchanting spot at the shore of Lake Como with his friend Niccolò Antinori, his mother, his aunt and a, perhaps only imaginary servant (compare: GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 12 February 1851 (servant; no newspapers); 7 June 1851; picture: Aloa)

SIX) IN SEEMING SECLUSION OR: NO NEWSPAPERS ALLOWED ON THE BALBIANELLO (1850-1860)

Otto Mündler (1811-1870)

(source: Kultzen 1999, p. 378; detail)

The decade of the 1850s does show a Giovanni Morelli who was fast in regaining his forces. But who still was torn between various, and rather diverse activities.

Genelli heard of a splendid life, the most splendid and serene life that, according to Morelli was possible in these miserable times, and Morelli indeed did spent some time at a castle of dreams: the Villa Balbianello at the shore of Lake Como in 1851, and with his Florentine friend Antinori, who was also, mentored by Morelli, preparing a trip to Germany, translating the play Egmont by Goethe into Italian, and besides that, tracing drawings by Genelli.(67)

One might say that Morelli distracted his forces, sharing his time and energies between too many things, but the decade does in fact show a Morelli who still could afford to be distracted.

Because on the one had his capacities and skills were not yet sought after, and on the other hand, if the economic situation was in tendency deteriorating, due to some newly imposed taxes on property, he still could afford to live on his income as a land owner, and moreover, he could even afford to become a collector (in 1856).(68)

His friend Genelli still provided Morelli, during the 1850s, with insights into the artistic scene,

for example as to painting dedicated to historical subjects like for example the fate

of the Counts Egmont and Horn: Belgian painter Louis Gaillait in fact had even paid Genelli a visit,

and in the above composition (shown here a small version of the motif) Genelli commended

the monk on the left as well as the two Spanish soldiers

(see Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 11 July 1853; 16 November 1852 (visit of Gallait))

But time had passed, and during the 1850s Morelli was concerned with the subject of history like probably in no other period of his life.

One has to recall that two of his beloved mentors, namely Gino Capponi and Veit Engelhardt, did also represent the subject of history, both of them contributing to the historiography of the church and of Christianity.(69)

But of Morelli’s three mentors, Engelhardt was to die in 1855, leaving Morelli in mourning; and as much as he also immersed into the reading of Capponi’s historical writings, and in the writings of other historians: his need of sensuality probably contributed to his being rather attracted to the subject of art than to the eros of archival reasearch and the reading of diplomatic dispatches.(70)

And if he, to a little degree, was to support Capponi, who had become nearly blind in the 1840s, that is: to support the nearly blind Capponi in the writing of a history of the republic of Florence – it is the very little degree, the small number of pages actually being dedicated to art within Capponi’s history that also testify to Morelli not being really inclined to the kind of history Capponi represented, who regarded the Berlin school, and namely Leopold von Ranke as a model.(71)

Morelli’s more or less secret plan was still to one day appear on the scene, providing Italy with a new comedy, but it was at the end of this decade that he also dropped this plan, having moved from Sanfermo to Taronico, nearby Bellagio, a village closer to the villas of his friends.(72)

While on the other hand he had renewed his friendship with Otto Mündler, the connoisseur of art, who, in some sense was to replace Bonvaventura Genelli as a mentor. Because, while the friendship with Genelli was apparently languishing to the end of the 1850s, in 1853 Morelli had met Mündler again, and art studies with Mündler, who represented the role model of living on applied connoisseurship, were becoming a more regular activity.(73)

And while this was happening, Morelli was attracted by the city of Turin and spent considerable time also there. Probably also because he had fallen in love again with a woman, a singer, but also because of Turin being attractive as the political and cultural center during the Risorgimento years; and because also, but probably also less and less, Turin representing, at least in his mind, a possibility to have his own plays, to have his own comedies represented on stage on day.(74)

It did, however never come to that, although in 1856 Morelli was still keen to hear the opinion of Francesco de Sanctis on some of these very plays. Of de Sanctis whom Morelli had also heard lecturing on Dante in Turin in 1853. And whom he had recommended to the founders of the new polytechnical institute at Zurich, who, at first had asked Morelli himself, if he wanted to become a professor in Switzerland, that is: to hold a chair, dedicated to Italian literature and aesthetics.(75)

This offer, fit to embarass Morelli on various levels, his chosen identity as an Italian (who now was asked to return to the origins of his family, that is: to Switzerland); and who had felt, at least felt more being a writer than being a teacher of literature, he had declined, recommending De Sanctis instead, who got the chair subsequently.

And whose opinion, whose mixed judgment he was to hear, a judgment that still seems to have caused new enthusiasm in Morelli. But after a last initiative in 1857, another mission to Turin, also this activity, like years before his studies in the realm of the natural sciences had languished, was languishing. In 1858 he was writing to Antinori (who had married in 1853) that his activity was dedicated to art studies and – collecting.(76)

Many years later, in 1881, when Morelli was supporting

his pupil Jean Paul Richter in putting together an edition

of the notes by Leonardo da Vinci, Morelli won also

the former secretary of Cavour, Isacco Artom, as a

subscriber of The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci

(see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 22 March 1881)

At the end of the decade, in 1859, Morelli did more observe the Second Italian War of Independence, than actually he did join it,(77) having become much more reluctant than, in comparison, he had been in 1848, when his enthusiasm had caused him not only joining the first war but to do something reminding of a Grand Tour, within the revolutionary sceneries, and not only the Italian sceneries.

And in 1859 he actually might have been at a point of not knowing at all what exactly to do in life, when, with the Italian unification, also his abilities were, all of a sudden, sought after by his compatriots, that is: his fellow citizens of Bergamo.(78)

Not, or only in part his abilities of a man of letters, or as a connoisseur of art. Hardly anyone knew of his studies that had become more intense with his spending more time with Mündler, with collecting and – with dealing. But as a politician, as a possible representative of the city of Bergamo his skills, his social skills, his education and probably his charisma, his intelligence was all of a sudden sought after. While the unification of Italy was on its way.

And it had certainly never been his idea to become a politican, but becoming a politician was an idea, after the idea of becoming a scholar in the natural sciences (or a doctor), and the idea of becoming a playwright (or just of staying to be a man of letters, a student) he had dropped.

Circumstances demanded his abilities, and all of a sudden Giovanni Morelli was someone to carry actual responsibility. With him immediately being able to focus, within that position as a representative of Bergamo and a player in the political scene, on questions related to art, his also rather new center of activity.

Staying in touch with Mündler, who was to hear the mourning of a man of letters having turned to be a politician.(79) And also being active, and more and more becoming active on his own account.

In politics, as well as also in dealing with pictures, above all in cooperation with English friends that were also friends and partners of Mündler. That is: in that he was to maneuver between politics and the business of attribution, and to negotiate, as we will see, between these two fields, that were to become, during the 1860s and finally, the two centers of his activity. Of activities, to be precise, that demanded also the skill of virtuoso maneuvering or better: intelligent maneuvering of someone with exquisite social skills and a passion for artistic things.

*

In 1853 Genelli had seen the actor Bogumil Dawison as Richard III

and mused, in a letter to Morelli (see Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 11 July 1853),

about how one was to play that role (shown above the portrait of Dawison as Richard III

by Friedrich von Amerling)

SEVEN) FORGED TO PROMETHEUS’ ROCK OR: ONE DECADE IN POLITICS (1860-1870)

If Otto Mündler, Morelli’s new mentor, was to hear many an outcry of a man of letters, forged to a Prometheus’s rock of politics(80) – also the decade of the 1860s – a decade in politics – showed Morelli as a fast learner.

It is certainly true that Morelli did dislike some aspects of political life and that some of his utterings – as to the stupidity of the masses for example that did not appreciate the politician’s engagement, and thanked him by spitting on him instead – read rather drastic.(81)

But after he had adapted to the fact that he was the elected representative of Bergamo, and after he again had found out that silent diplomacy might, in some cases, be more succesful than a high-profile appearance on the stage of the parliament, he might have become an not completely unsuccessful politician, at least someone who certainly knew how to pull some strings (compare chapter Interlude I).

While it certainly was also true that he, at times, was wishing to return to his much missed quiet private life, dedicated to reading and studying of pictures, like a cultured hermit.(82)

Florence was becoming the new Italian capital in 1865 (picture: lapuntasecca.it)

The decade of the 1860s probably was the most torn period in Giovanni Morelli’s life. Who had now to share time and energy between the two new centers of his activity: art studies and politics.

And new was that he did face actual pressure, even various types of pressure: economic pressure, time pressure, the burden of responsibility and not the least – the pressure of political adversaries as well as the rivalry, or the seeming rivalry of other art historians that he was to regard as his antagonists.

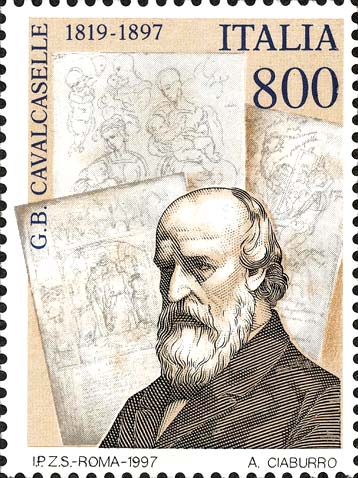

Above all the rivalry with Italian art historian and connoisseur Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle (see particularly, and with a chronicle of the history of a disagreement, chapter Visual Apprenticeship II).

More hidden in all that was also the fact that the becoming aware of the importance of the detail in the context of art studies, of studies that were dedicated to the whole ›forest‹ of art, the entireness of Renaissance painting very in particular, could go along with the becoming aware that connoisseurship had, indeed, also a nightmarish side to it. Especially if one was to enter an embattled field as was – and is – the mere attributing of pictures, of determining of authorship, of giving names.

And while this was happening, while the visual apprenticeship of Giovanni Morelli went through a phase in which the vision of the whole, if juxtaposed to the problem of the detail, might have seemed, at times, simply overwhelming. And it is little surprising that Morelli did, for very long years, not accomplish essays or books, not to mention catalogues or guides.

All the more because he was someone, as he knew, and as also Genelli knew, lacking the patience for systematic studies that only too easily could bore him.