M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM A Christ in Profile  |

See also the episodes 1 to 19 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

And:

A Christ in Profile

(21.9.-22.9.2021) While conventional iconography of Christ often gives artists the opportunity – or even demands

them – to depict Christ frontally, there are virtually no iconographical conventions that would demand artists to depict

Christ in profile. Certainly, there are still many occasions and motives to do that (and below we will look at some

examples of how artists have done that). But there does not seem to be a necessity of such representations (rather being

associated with the representations of Roman emperors for example – on coins).

On the other hand we see conventions in art to depict these emperors and other dignitaries in profile, and if an interest

does exist to see Christ represented, as one might say, it is only natural that Christ is also represented in terms

of such conventions. And it is as obvious as it is today that also at the time of the Renaissance such (often ardent)

desire to see Christ represented visually as realistic as possible did exist, a desire which seems to be the natural

outcome of a stance of veneration that produces the wish to see, to recall and to venerate a person that one wishes to

be present as near as possible and ideally also: to always be present (again).

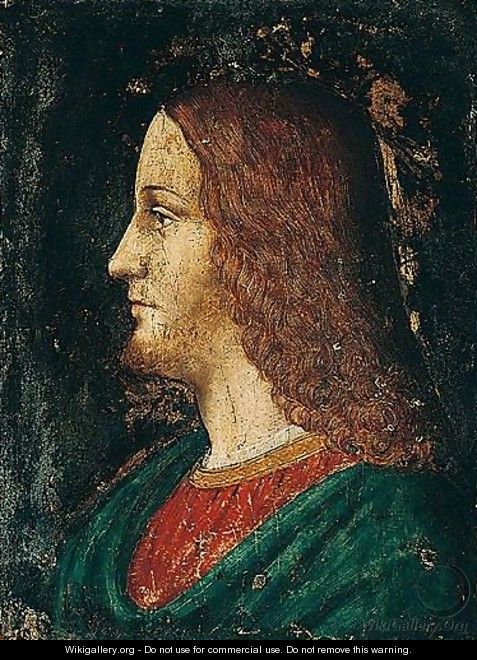

In this twentieth episode of our New Salvator Mundi History we will look at a picture of Christ represented

in profile that Federico Zeri had attributed to Francesco Melzi, our supposed main author (or co-author) of

the Salvator Mundi version Cook. This gives us various opportunities, such as to discuss (and to question) this

attribution by one of the great Italian connoisseurs. But also the opportunity to look for alternative attributions,

and to generally broaden our view as well as to expand our understanding of artistic practices and possibilities. This

will finally lead us also to look at another – in some sense: Leonardesque – representation of Christ that combines the

frontal representation of Christ’s face with a representation of Christ’s body in profile.

(picture above and in title: fondazionezeri.unibo.it; bg in title: Boruah)

One) Choices, Options and Traditions

In social networks of today people have (as I have recently noticed) ›artificial intelligence‹ combine the Salvator

Mundi with the Turin Shroud and other pictures to create images to suggest (to themselves as well as to other people)

how Jesus might have looked like. One might say that, today, people have technical options and choices to – eclectically

– rework any tradition they like, drawing from whatever tradition they like. And Leonardesque representations of the

traditional iconography (as well as authentic works by Leonardo) have become representative. Brief: Leonardo is one major

source to draw from. But how was this, let’s say: in 1517?

The travel account by Antonio de Beatis which is one major source for Leonardist to draw from – because Antonio had

visited Leonardo at Amboise in 1517 – is remarkable in many respects. It is remarkable because this secretary of a

Cardinal had the opportunity not only to visit Leonardo and his workshop at Amboise personally. It is also remarkable

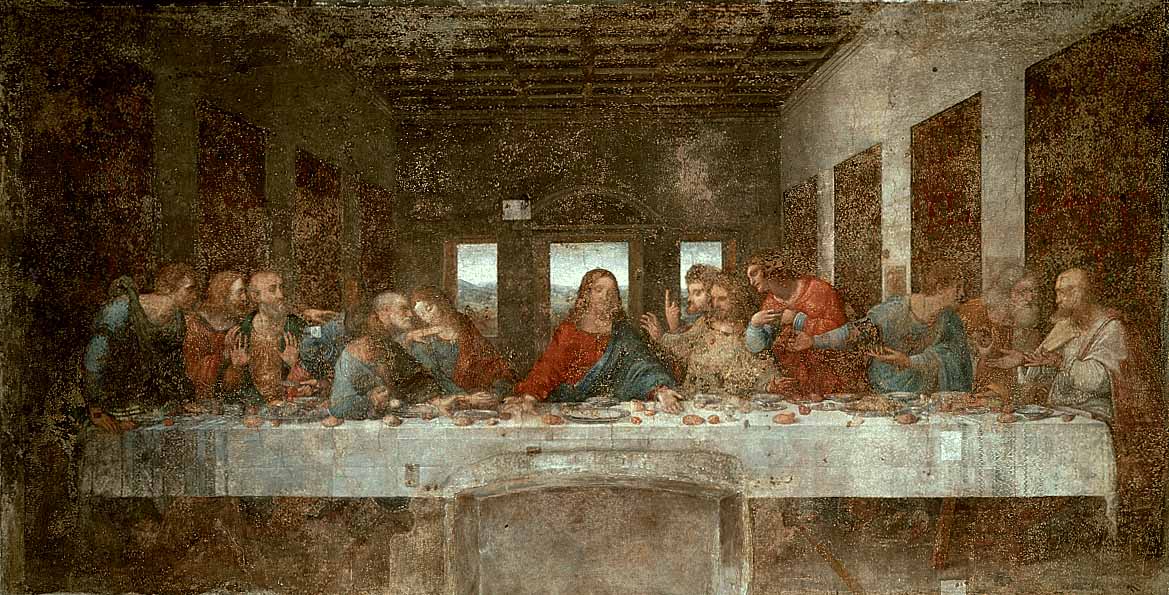

because Antonio could see also other sights on his trip – as for example the Last Supper by Leonardo at Milan, and as

also the Ghent Altarpiece (Antonio de Beatis, interestingly, only refers to the images of Adam and Eve). And there is another,

virtually unknown detail: at Chambéry, in Savoy, the visitors were also shown the now so-called Turin Shroud, and – this

is the crucial detail – the extant manuscript copies of this travel account have either drawings of the shroud or space

left for a drawing (as in one case) and thus include(d) reproductions of this particular image, widely thought to be the one

authentic image of Jesus Christ (see Pastor (ed.) 1905, p. 148, note to line 35). In his mind, one might say,

Antonio could combine all the impressions he gathered on his trip with the Cardinal; but even the space left in one

manuscript seems to show that one particular image was given priority – in that it had to be reproduced in some way. And

this image was not one by Leonardo.

And now we have to ask: how might this have been for Leonardo himself, let’s say: in 1494, when he was about to create

one representation of Jesus Christ that was to become representative, and today, more than 500 years after creation,

still is one of the most representative representations of all? Didn’t Leonardo have to make choices as to the traditions

to rework, as to the traditions to draw from?

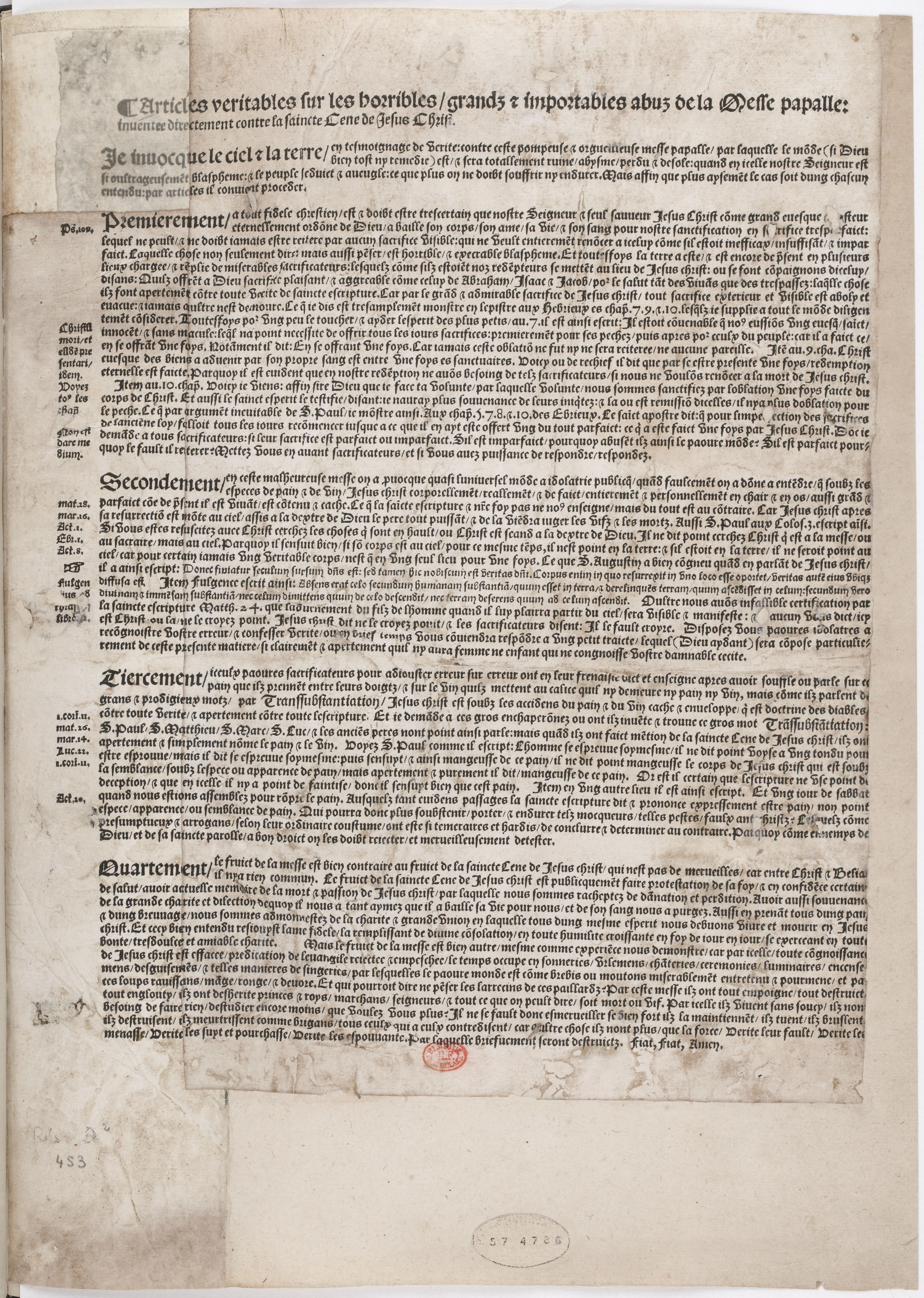

He certainly had. And not only visual traditions. Because in the second half of the 15th century also the so-called

Letter of Lentulus was circulating (see Lüdeking 2014). This apocryphal letter, containing a description of how Jesus looked like,

certainly was known to artists. As the above image does show, it was also combined with pictures representing Jesus (and

here we have another example of a Christ in profile), and the tradition that Leonardo in some sense ›created‹, by creating

›his‹ representations of Jesus Christ seem to have much to do with this text, as they might have to do with other, visual

traditions. In some, more heretical sense, one might even say that Leonardo, by faithfully sticking to an apocryphal text

as the Letter of Lentulus, he actually created a representative tradition whose ›authenticity‹ also might be questioned.

But since the Letter of Lentulus, in some sense, ›only‹ verbalizes an already existing visual tradition, it is virtually

impossible to tell the one from the other. What is interesting, however, is that the Letter of Lentulus names colours (of

hair, of eyes), and these designations of colour, at least as for the colour of eyes, vary in various translations. Did

Jesus have brown eyes, dark blue eyes, or blue-green eyes? Artists had to make choices, probably resulting with

pluralism, with eclecticism, simply because not everyone knew Latin, and because the Latin was ambiguous. But still one

has to say that Leonardo was known to be very faithful as to written sources, very carefully thinking and rethinking how

to translate a literary tradition into a picture (see Marani 2005, p. 139). It is not known if Leonardo ever considered

the now so-called Turin Shroud to be an important source, but his contemporaries did, as Antonio de Beatis did, which

might lead one to say that also Leonardo might have been confronted with eclecticism. And part of this contemporary

eclecticism at around 1500 was the following text (from the Letter of Lentulus; English Wikipedia):

»Lentulus, the Governor of the Jerusalemites to the Roman Senate and People, greetings. There has appeared in our times,

and there still lives, a man of great power (virtue), called Jesus Christ. The people call him prophet of truth; his

disciples, son of God. He raises the dead, and heals infirmities. He is a man of medium size (statura procerus, mediocris

et spectabilis); he has a venerable aspect, and his beholders can both fear and love him. His hair is of the colour of

the ripe hazel-nut, straight down to the ears, but below the ears wavy and curled, with a bluish and bright reflection,

flowing over his shoulders. It is parted in two on the top of the head, after the pattern of the Nazarenes. His brow is

smooth and very cheerful with a face without wrinkle or spot, embellished by a slightly reddish complexion. His nose and

mouth are faultless. His beard is abundant, of the colour of his hair, not long, but divided at the chin. His aspect is

simple and mature, his eyes are changeable and bright [German Wikipedia: ›dark blue, clear and lively‹]. He is terrible

in his reprimands, sweet and amiable in his admonitions, cheerful without loss of gravity. He was never known to laugh,

but often to weep. His stature is straight, his hands and arms beautiful to behold. His conversation is grave,

infrequent, and modest. He is the most beautiful among the children of men.«

Two) Melzi-Attributed

I don’t know on what basis Federico Zeri had attributed the above shown painting to Francesco Melzi, but I suspect that

he had done so, linking this picture (whose present whereabouts are unknown to me) with the above shown drawing,

attributed to Francesco Melzi and showing his master: Leonardo da Vinci.

In my view there is an obvious reason to indeed link these two pictures: because both seem to be the outcome of

veneration. It is about faith as to the painting of Christ and according to a stance of veneration as described above,

and it might be about a loving memory as to the portrait drawing showing Leonardo. The drawing might also have been a

sketch meant to be the basis of a painting. And as to the depiction of Christ, it seems to me that its function might

have been a careful observation of the physiognomy of Christ in terms of a study, probably also drawing from the Letter

of Lentulus, because the having of a Christ in profile might have been of use, in case such portrait was meant to be

inserted in a depiction of Christ interacting with other figures or pictorial elements. Because, as we will see, Christ

appears in profile, if being in interaction with other figures or elements – and not primarily with the viewer.

I am not going to challenge the attribution by Zeri in terms of proposing one particular alternative. What I should like

to do is to broaden the perspective, without actually picking an alternative. But on a general level some things have to

be said first.

First of all I am thinking that the days are over when it was possible to find acclaim in scholarship with giving mere

opinions as to attribution. Scholarship expects someone giving an opinion to back up such opinion with reasons,

arguments, i.e. to substantiate his or her opinion, which is also expected to be worked out in a transparent way (what is

done outside the realm of scholarship is another matter; but scholarship still is, or still should be the reference in

society as far as knowledge production is concerned). While an opinion can be regarded as a hypothesis, i.e. as a

starting point, it cannot be – by principle – the end of a debate, even if the opinion has been voiced by a great

authority such as Zeri (this can only mean that the starting point might deserve more attention than the starting point

of an amateur, but not only this is unddoubted, because amateurs can have good intuitions, while authorities, people

with status, might be blind for the obvious).

Secondly I am thinking that the days are over when it was possible to simply put homeless Leonardesque pictures into

categories such as ›Melzi‹ or ›Salaì‹. As to Salaì many high quality pictures have been put into such warehouse, pictures

that simply do not fit with Salaì as the author of the one signed and dated picture (a Christ, dated 1511). And as

far as Melzi is concerned, the one undoubted picture might be, in case the signature could be traced again, the

Vertumnus and Pomona of the Berlin Gemäldegalerie (a picture that, again, we discussed in our last episode).

But not even this is certain, nor the attribution of the drawing depicting Leonardo. If virtually all is hypothetical,

one should say so – avoiding false declarations of certainy, or the suggestion that scholarship has solved a problem.

Amassing hypotheses might lead to solving problems – but the work of solving problems in a scholarly way still has to be

done. In the case of the Christ in Profile such work has not even begun. Or we might begin it now with some first

steps.

Three) Painters of Reality

In my view it would be interesting to start with looking at Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo. This artist and theoretician speaks with

admiration of a Christ in profile by Gaudenzio Ferrari (an artist who experimented with anamorphosis, and Lomazzo saw this

representation of Christ distorted – as well as undistorted). Since Lomazzo has shown Christ in profile in at least two

of his own paintings (above his Adoration in the Garden; here the ear of Christ is not shown, but covered with hair

as in the Melzi-attributed picture; in the other one the ear can be seen), he might be seen as someone of interest.

Pictures from the circle of Lomazzo even show comparable folds as can be seen in the Melzi-attributed picture, but the

ground seems to remain as shaky as in the case of Gaudenzio Ferrari himself. Comparable elemens can be spotted, but we don’t

have a configuration of clues to offer that could serve as a structure, a combination of elements, to narrow the picture

considerably. Instead we choose thus to broaden the perspective – also because the only comparable element, exept the

very general likeness of hair – is the high front in both the Christ and the drawing showing Leonardo. But is this enough

to base an attribution upon? Without even turning to other Melzi-attributed pictures? Or without realizing that this same

general likeness shows also in this Tullio-Lombardo-attributed relief (below)?

I do think that this is not enough, and that the perspective instead should be broadened, so that other candidates could

be discussed, even if such discussion would – in the end – lead back to Melzi, because we would have come to know him

better.

Above shown is also a recently auctioned work that – with or without reasons – has been associated with Bernardino de’ Conti. But a

cluster of pictures of Christ shown in profile, a cluster as in the case of Salvator Mundi pictures, representing the

whole circle of Leonardo, we don’t seem to have.

Four) Examples Within Pictures

In the above picture, a Road to Calvary with Veronica by Giovanni Cariani, we can observe how a Christ in profile is

interacting with another figure within the picture. And since this figure is Veronica, Christ is even interacting here

with a figure representing a specific pictorial tradition herself – the Veil of Veronica. Interestingly Veronica is, here,

on this occasion, not given frontally, although, to see the cloth with the picture of Christ, would demand it.

But the demand of the viewer, here, may come secondly, because, having identified Veronica as Veronica, we know that, on

the cloth, an imprint-like frontal ›portrait‹, better: a ›true‹ image of Christ can be seen. The ›truth‹, here, is out of

question and, paradoxically, must not be shown. Among the Leonardeschi, it seems, depictions of Veronica are rare, but a

recently auctioned conventional version had been linked with Marco d’Oggiono.

A second example of a Christ in profile within a picture with multiple figures is the above Supper in the House of

Simon Pharisee by Moretto da Brescia. What is interesting here is the smart composition that avoids that a representation

in profile results with something rather stiff and statuesque. If Christ is sitting rather straight here, it makes good sense,

since the iconography is about the lack of hospitality (which concerns the other figures standing as well as one sitting,

whose posture is skipped in various ways, almost as being choreographed as wriggling, with Christ as a reference, which

makes – literally – very good sense) while the second level of interaction happens between Christ and the woman at his

feet, a sinner, but showing the necessary signs of respect, and contrasts with the behaviour of the other figures.

With a third example, perhaps unexpected, we go back to Leonardo himself. With this example, the blessing Christ child

from the Paris version of the Virgin of the Rocks, I want to announce one of the next episodes of this history, which

will be dedicated to the ›history of gestures‹. We will show that the ›worldly farce‹ around the pentimento in the

Salvator Mundi version Cook, is indeed a wordly farce, since two versions of blessing hands – with thumb bent or with

thumb straight – existed long before any Salvator Mundi painting, and namely in early Leonardo paintings (and the

pentimento, therefore, can be nothing but a faint echo of alternatives found a long time before). What we do here, by

contemplating how depictions of Christ given in profile and interacting with other figures or pictorial elements work

within pictures, is also to prepare ourselves to see that visual ideas not necessarily come again literally. We see a

blessing Christ here, with thumb in the so-called ›final position‹ which means that the thumb is bent, but here we see

the hand in profile, and not, as in the Salvator Mundi pictures, frontally. Still it is the same idea: a blessing gesture

– here associated with Christ child – that is not wholly conform to the so-called Latin blessing (which would require

the first three fingers straight). But this can be explained in two ways: it is Christ child here, playfully doing

such gesture, and secondly, blessing means a movement of hands, and the fingers have to be moved into the position of a

conform blessing gesture. This has not fully happened here, as it has not yet fully happened in the Salvator Mundi

series, which, also, makes good sense, because a picture usually shows a moment in time, and this moment can be the

moment a hand prepares for a blessing – with a thumb that is not yet fully straight, as actually would be required.

But the subtle nuance is crucial – a hand preparing for giving a blessing alludes to the possibility of receiving a

blessing. A picture cannot give it anyway, as much a viewer would want it, and it makes very good sense, again, that a

picture works as a sign – referring to what is possible – and not as pretending to be and to offer what it cannot be or

offer. We are observing here a meditation about blessing, if one likes so, inviting a viewer to do the very same thing.

Five) Frontally and In Profile

And finally I’d like to announce a new – and also Salvator Mundi-related discovery here. In 2012, one year after the

publication of the Salvator Mundi version Cook, the above shown picture was auctioned as by ›Follower of Luini‹. Only

in 2017 more broad attention was drawn to the presently undoubted, signed and dated picture by Salaì (above on the

right). Comparing both pictures I find it hard not to think of the same hand (picture above left: artnet.com), and

I dare to propose the hypothesis that these two pictures may be by the same hand: by Salaì.

The supposed ›new‹ Salaì (above on the left) might be seen as a rather bizarre picture at first sight. But it also turns

out to be fascinating – for a number of reasons. A first reason might be that, according to the auction house, the

picture is on walnut. Secondly: we see Christ while being mocked here. And while Christ is being mocked, he turns his

face to us, the viewers, since he is actually standing with his left shoulder turned to us, so that we actually see his

body in profile, while we see his face frontally, as if he would be asking ›who are you?‹, ›are you among those who mock

me? or what exactly is your position?‹. And this is a way to engage a viewer very directly, a way that I also find very

interesting, although or just because this seems to be a picture meant to make a viewer feel very uncomfortably. On some

level, on might say, this is a terribly direct picture.

The third reason has to do with the hair, since what we see – can only be named vintage Salvator Mundi hair. It is rather

excessive, yes, how the artist (possibly Salaì) is representing hair – like water. Like the turbulences of water at the

bottom of a waterfall. But on the left side of the picture the hair is so obviously close to the hair in the Salvator

Mundi version Cook, including the double helix, that I am tempted to slightly correct my earlier position concerning

possible contribution of Salaì to the Salvator Mundi: he might have contributed slightly more to the picture that I

am still considering to be a Melzi/Leonardo/Salaì hybrid, made at Amboise – perhaps based on one of the pictures from the

Salaì group. And I am going to investigate also the issue of hybridity more in depth in one of the coming episodes, named

›A Renaissance of the Hybrid‹.

Selected Literature:

Ludwig Pastor (ed.), Die Reise des Kardinals Luigi d’Aragona durch Deutschland, die Niederlande, Frankreich und

Oberitalien, 1517-1518, beschrieben von Antonio de Beatis, Freiburg i. B. 1905

Karlheinz Lüdeking, Der Leib und die Lettern. Dürers Selbstporträt von 1500, in: Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus 11

(2014), p. 7-40

Pietro C. Marani, Leonardo. Das Werk des Malers, Munich 2005

Further Reading:

Rossana Sacchi, »Oh Blessed, Excellent Mind and Hands!« Lomazzo’s Admiration for Gaudenzio Ferrari, in: Lucia

Tantardini / Rebecca Norris (eds.), Lomazzo’s Aesthetic Principles Reflected in the Art of his Time, Leiden / Boston

2020, p. 18-39

The Bottega of Leonardo da Vinci

The picture of the bottega of Leonardo da Vinci is not as blurred as one might imagine (for details see Seidlitz 1935, p. 530; Marani 1998). We will focus here on the early and middle years (up to 1512), and not on the late years, and one might begin with saying that with Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono we see two figures enter the orbit of Leonardo at the beginning of the 1490s that we believe to know rather well. We also see Salaì enter the orbit, at a very young age, and we have, in addition to that, a couple of names, names of figures that we do not seem to know very well, or not at all (a Giacomo, Giulio Tedesco, Galeazzo). Last but not least we have the Giampietrino problem: Giampietrino enters the scenery, but it is a matter of controversy (as far as this question is debated at all), when, since also Giampietrino is still very young.

It is noteworthy that Marco d’Oggiono, already at the end of the 1480s, seems to have had an own apprentice, and that Marco and Boltraffio did create the Pala Grifi together (a picture today in Berlin; picture above), even before Leonardo began to work at The Last Supper in 1495. Due to the work of Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi we today do know more about Francesco Galli, also called Francesco Napoletano, who did die in Venice as early as 1501. One might imagine that Galli went to Venice with Leonardo in 1501, and if Galli, during the 1490s, for example might have cooperated with Marco, we would have found an interesting perspective: since, if only one single picture of the Marco group would be associated with Francesco Galli/Francesco Napoletano, we would have a picture with hand option 2, a picture that must have been created before Galli died in 1501. Which would mean that hand option 2 must have existed early, and my theory of the pentimento in version Cook as a mere switching from (preexisting) option 1 to (preexisting) option 2 would be positively proven as well as the theory of the pentimento supposedly showing the creative energy of genius (changing his mind) would be definitively falsified.

Brief: in the 1490s Leonardo mentions once that he had paid ›two masters‹ (probably Marco and Boltraffio) for two years; and once that he had six bocche to feed (probably again Marco, Boltraffio, plus Salaì and some of the unknowns).

Below a rather early Marco picture (according to Janice Shell), the Young Christ Blessing of the Galleria Borghese:

And here is a picture (not the only known picture) by Protasio Crivelli, formerly the apprentice of Marco d’Oggiono (picture by Sailko; the date appears to be 1498; location: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte):

In 1501 (3.4.) Pietro da Novellara informs Isabella d’Este that Leonardo seems to live ›from day to day‹ (see Marani 1998, p. 14). And he has seen Leonardo intervening from time to time in portraits done by two of his garzoni (»fano retrati«). But who are these, and which portraits are these (if this would have been about a Isabella d’Este portrait, Pietro would have noted; and after the Sforza had been expelled, portraits of court ladies and courtiers made no sense)? After having written on the picture of a young woman in the Columbia Museum of Art in one of the last episodes, I would now suggest the following:

Leonardo might have done a portrait of a Sforza court lady in the early Milanese years (and still in the Florentine portrait style), a portrait in terms of a drawing or a cartoon. He might have begun also a painting, but since the Sforza court got expelled and exiled after the French invasion, he might not have finished such portrait. He might instead have used it for the instruction of his garzoni: the Columbia picture might have been the one begun by Leonardo (as he seems to have begun portraits with the face, as later in the Mona Lisa), a picture that he might have had a pupil finish, with him retouching it again, adding some lustre. The picture in a private Russian collection might be a second version that he had a pupil repeat (after the first version and the drawing, respectively the cartoon). The Columbia picture shows much gusto for the grotesque, the second version less so, but still to some degree. Thus we would see pictures that have their origins in the first Milanese period (and even in the early Florentine period), but were actually done later (after 1500). And Leonardo might have had a hand in the Columbia picture whose head with the hair as well as the ornated hair net superbly being modelled into the dark is of exquisite quality (as also a single one pearl is, while other pearls are rather mediocre as also the bust and the modelling of the dress is). We see, as I have attempted to show in episode 13, two pictures that fit into the context of Leonardo’s thinking and doing rather than into the context of Boltraffio’s autonomous work:

In 1504 a Jacopo Tedesco, in 1505 a Lorenzo (di Marcho) enter the orbit of Leonardo.

In around 1505 Fernando Yáñez enters the orbit of Leonardo, helping him with the Battle of Anghiari (as also does Riccio della Porta). Yáñez cannot be the author of the Prado Mona Lisa, if the Louvre Mona Lisa was finished only years later, since the dates (showing that Yáñez was active in Spain after 1506) do not allow to postulate it. In works of Yáñez done in Spain, however, we find echoes of Leonardo’s works (see the example below).

Around 1507 Francesco Melzi becomes a pupil of Leonardo (and also a sort of secretary).

In 1511 (or even earlier) Giampietrino is an autonomous master.

In 1511 Salaì seems to have created a (signed and dated) picture of Christ:

In around 1511 we see Marco, Boltraffio, Giampietrino and – Giovanni Agostino da Lodi in close contact, not only because we have a source indicating exactly that – we also have pictures indicating exactly that, and one of these pictures seems to be even dated (but the ›date‹ – ›XII‹ – is rather referring to the ›age of Christ‹):

The Prado Mona Lisa (below) was probably begun at the time Leonardo also started reworking or completing the Louvre Mona Lisa, probably due to Giuliano de’ Medici wishing so, and hence perhaps in around 1511/12.

In around 1517 Marco d’Oggiono is cooperating with Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (see Shell, p. 173).

***

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

»…in the evening at twenty-two o’clock we saw the Holy Sindon or Shroud«, Antonio de Beatis is writing in his travel account, his trip across Germany, France, the Netherlands and Northern Italy having enabled him to recall, as an eye witness, essential sights of the visual culture of Europe in 1517/18. These sights included, as said above, the Ghent Altarpiece, the Turin Shroud and also Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan (picture of the Turin Shroud: Dianelos Georgoudis). Only the now so-called Turin Shroud, however, did apparently stimulate him to include a visual reproduction, a drawing, into the manuscript copies of his account.![]()

See also the episodes 1 to 19 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS