M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

A Fox on Seeing with the Heart (Visual Ideologies I)

A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

(Picture: mnn.com)

(Picture: pinterest.com; Mr S)

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry might be called an iconic book of our time. Less visible perhaps is that one particular wisdom, one particular message from that book might also be called common knowledge. And still art historians, at least until now, have never taken the challenge of that particular lesson. The challenge of ›It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye‹.

But this is exactly what we do here: an exhibition, dedicated exclusively to a discussion of that wisdom, that message, that provocation, from an art and cultural historian’s perspective.

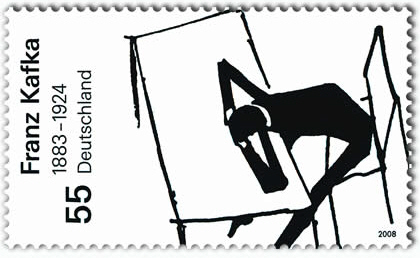

(Picture. philatelie.deutschepost.de)

Castle, The:

Some interpreters say that by reading Kafka’s The Castle and Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince you would be reading the quintessential two books of the 20th century. This is an interesting perspective, but perhaps this is also another bold simplification (see Simplification, Boldness of), with Kafka representing the Black and Saint-Exupéry the White. Keep in mind that The Castle remained unfinished as a novel, and it might well be that Kafka had had in mind to finish that novel with the castle, i.e. the power of the castle showing also some grace towards the alleged land surveyor K. (as the castle is, in the beginning of the novel, showing a sense of humour, or at least sportsmanship, by accepting to enter into a sort of game with K.).

In any rate it is long due to dedicate also an exhibition, especially from an art historian’s point of view, to these charismatic two draftsmen: Saint-Exupéry and Kafka.

Ford, Richard (novelist):

According to a recent interview (NZZ, 19 December 2015, p. 47) shaken by finding that among writers was a great deal of consensus as to the basic properties of literature. Asked for examples Ford quoted Emerson and then our classic (albeit here inverted): ›what is essential is invisible to the eye; it is only with the heart that one can see rightly.‹ Thirdly Ford quoted Octavio Paz, to sum up in the end that the sources of literature were invisible. And more than that: they do not even exist. One has to create them, by power of imagination.

(Picture: rauserbegins.com)

French Teacher:

If your French teacher at school happened to torture you with the Little Prince; if, today, you need medication if you only are hearing the words ›dessine-moi un mouton…‹; if you got into a lifelong, but seemingly pointless fight with the French language that first seemed to welcome you, but then only frustrated you, here is what you need, here is the best medicine that I am able to give you:

First step: you must become aware that your French teacher, he or she, did not teach you the Little Prince.

No, she taught you The Castle.

Because what you experienced is exactly what the land surveyor K. is experiencing in the Castle novel, a lenghty fight with a superior power that first seemed to welcome you, but then… well, then you got entangled into a lenghty fight with that power, from which resulted your Little Prince neurosis.

The second step would now be to a) forgive your French teacher at school, no, even to thank her that she taught you the Castle; and b) to forget about your neurosis and to take a fresh look at the Little Prince here with us.

(Picture: storyboardthat.com)

Fox (in popular culture), The:

See here.

Heart, Eyes of the:

An early source is Ephesians 1:18:

I pray that the eyes of your heart may be enlightened in order that you may know the hope to which he has called you, the riches of his glorious inheritance in his holy people,

(Picture: goodbibleverses.org)

Invisible, Iconography of the:

What a lure it would mean to write a history of art along this principle:

›It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.‹

Is it a principle? And is there, perhaps, a counterprinciple? As for example: ›What you see is what you get; all essential is on the surface‹?

We might say that all great art has a visible side and an invisible side. If we think of Symbolism, of Action Painting, the visible refers to the invisible, to someone thinking (and symbolizing), to a subject leaving a trace.

(Picture: DS)

(Picture: wikimedia.com)

But if I had to come up with only one example that indeed embodies the principle that the more essential is invisible to the eye, I would come up with this painting by Rembrandt. Since visibility, here, does indeed relativize visibility. At least this is one way to read this painting:

A couple in conversation; he, a Mennonite preacher, she, his wife, and while they are seen in conversation, we see that, while being immersed in conversation, they do not exactly look at each other (he perhaps, if rather indirectly, while his hand is making a gesture that seeks for her eyes, but she certainly is not looking at him, and perhaps she does know his gesture, and it is enough that she hears). And still: this couple seems to be immersed in vital conversation. And this is the vitality of Rembrandt’s art.

Visibility points us to the world of the mind, of the intellect. To the possibility of connecting via language. And this is one step towards making a case that what is essential is invisible to the eye.

But this is not all.

The not looking at each other points to a deep, and hopefully heartfelt mutual understanding of these two souls. Who, apparently, can bear to be together, in conversation, and this while their eyes do not feel a need to look at each other here.

And this would be our second step towards making our case: because they do know each other well, which means here: that they are, as a couple should be, capable to see each other with their heart, and the bond of speaking, of discussing, does not need the bond of looking at each other anymore. This is deep understanding, trusting, relying on each other.

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in Bed (1983)

(picture: metmuseum.org)

Compare this with the more modern couple shown by Nan Goldin. Visibility, here, also does relativize visibility. Since her gaze, in a sense, is nothing but a question mark. And the whole picture is, essentially, nothing but this one question: have they found each other or not; or shall they? And where is he at this very moment? Immersed in introspection? And looking at what?

And the answer, if it can be found at all, lies in the invisible, in the beyond of this picture. In that world where human souls may find each other, touch each other (as we are touched by music, as the expression of human souls’ life), or not find each other, knowing that the essential, the ability to find heartfelt relations with persons, with living beings, with works of art, can visibly be alluded to, in works of art as in life, but always will remain invisible. Because it is an inner ability. Our inner sensitivity, our soul, that allows us to make sense of each other emotionally and intellectually. And of works of art.

(Picture: DS)

Museum, The:

The big museums like the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Hermitage can easily be misunderstood as common museums. But these are not. The big museums are rather encyclopaedias with a museum café attached to it. We face a similar situation as the little prince faces when realizing that there are millions and millions of roses in the universe (as there are thousands and thousands of pictures in our universe, here: the art universe, or the universe of the one big museum).

But the task is rather easy. It is about developing a personal relation with chosen objects.

Choose objects to look at that have something to do with you. As an individual.

And you will have relations with chosen objects that also will develop. Into friedships, and sometimes lifelong friendships. You will know that also in the big museums there are friends. That await your visit again. Because they know that this is not about the history of the big museum itself, not about the aura of famous objects (being famous for being famous), not about the history of the work of art as such (which means: without you).

But about what is between you and the chosen object. As it is for the little prince about the relation between him and the one rose (see: Rose, The) about which he really cared, or about him and the fox, with whom he spent time with, and whom, by doing that, he (as Saint-Exupéry has it) ›tamed‹. Which means: he really got to know the fox and developed a personal relationship with him.

(Picture: uni-marburg.de)

Plane Crash:

Opinions as to whether Saint-Exupéry was a great pilot himself seem to be divided (consensus might exist as to him often having other things on his mind than piloting, and this also whilst piloting…). But in our context ›plane crash‹ might read, on a metaphorical level, as ›crisis‹ anyway. On this level the Little Prince is about a crisis in life. And crisis might read as: a time in your life when it might be necessary (and hopefully fruitful) to rethink principles, to be reminded of principles (and the prince himself does exactly that: reminding).

In other moments this, the rethinking, the reminding, might be less good a strategy (see: Simplification, Perils of). In other words, after crisis has been dealt with, it is about implementing principles in real life. Which might require compromises (see again: Simplification, Perils of), and also sharp-eyed looking.

ps: Kafka attending the Brescia air show (see here): »Ordnung und Unglücksfälle scheinen gleich unmöglich.«

Renaissance, The:

A Renaissance Reader of the Little Prince?

›It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.‹ What would a Renaissance artist have made of this? Well, the less pagan might have felt like reminding us that indeed the ›scripture was the better picture‹. But the more pagan might have nodded in a different way, saying: ›yes, we are focussing an the physical body and its precise representation in picture now. But we do this not the least, for example in portrait, to represent the inner life of people. So our looking (and showing) aims at the invisible as well. Since we all know: it is about soul. In other words: about the essential, our inner living.

ps: we choose as our example the beautiful representation of a female reader of Petrarch by Andrea del Sarto: what’s on her mind? Do we all know it? Essential it might be, but is it visible?

ps 2: yes, the more pagan artist also did remind us that the Renaissance was about precise representations of space as well. All contemporary Pokémon Go people do know that. And they also do know: Pokémon Go presupposes exactly this, and something else: the wish that not everything is yet visible, that reality, at least in games, might be augmented (if cute little monsters are to be counted among the essential, we don’t know; perhaps they only exist to remind us that something might be visible and invisible at the same time, leaving us undecided what indeed is essential).

Rose, The:

(Picture: Picture: cmoa.org ; René Magritte)

(Compare also the meaning of the name of Nasrin (wild rose) within Navid Kermani’s great and monumental 2011 novel Dein Name; and for this novel see also here)

Simplification, Boldness of:

The reminding of principles might have something bold and heroic to it, if circumstances seem to demand rather pragmatism and realism (see also: Simplification, Perils of). But the more absurd it might seem to remind of principles, the more creativity might be the result. Because principles need being implemented in life. And implementing of principles does require creativity (including as to how to fight, or to avoid obstacles).

As to our imagined ›Art history of the invisible‹ the same applies: it might be refreshing to look at the history of art according to just one principle, and to speak about the unseen (in principle). Knowing that there is much (visible), and knowing that also a history of the invisible is about creativity (and, fortunately, yet might make it visible).

Simplification, Perils of:

›It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.‹ Even people who basically have understood this principle can find themselves in situations where they have responsibilities for other people, including for their financial wellbeing (see: World of Numbers, The). Don’t annoy these people with reminding them of the principle: they already might know it. And they might know something else as well: it is not possible to deal with life according to just one principle. Because mere understanding of our principle does not mean that your responsibilities (your caring for other people) does allow you to act according to the one imperative: ›more emotion, please!‹, ›more empathy!‹ (or just: ›listen to your heart!‹).

So be careful. Under certain circumstances it might be necessary to remind the principle itself, but under other circumstances realism and pragmatism might be required. And this means: sharp-eyed looking.

Visual Person, A:

Franz Kafka is supposed to have said ›I am a visual person‹. Only that this is the Kafka of Gustav Janouch and Kafka scholarship tends to dismiss, if not unanimously, the conversations with Janouch (the quote on p. 215) as a source. What we know for sure is that Kafka wrote to Max Brod that the ›natural state of his eyes‹ was that they were ›closed‹. ›Closedness is the natural state of my eyes‹ (see Gerhard Neumann, Franz Kafka. Experte der Macht, Munich 2012, p. 73). What a fox-like Kafka! And compare!

World of Numbers (world of the adults), The:

The world of numbers, the world of the adults (and their visual ideologies), in sum: the Global Financial Crisis, we already have discussed here.

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM The Virtual Museum of Art Expertise Thank you for visiting |

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES | FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS | HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION | ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

I. Löffler, The Little Prince as Seen by Franz Kafka

(Picture: DS)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS