M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM A Renaissance of the Cartoon |

See also the episodes 1 to 13 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

And:

A Renaissance of the Cartoon

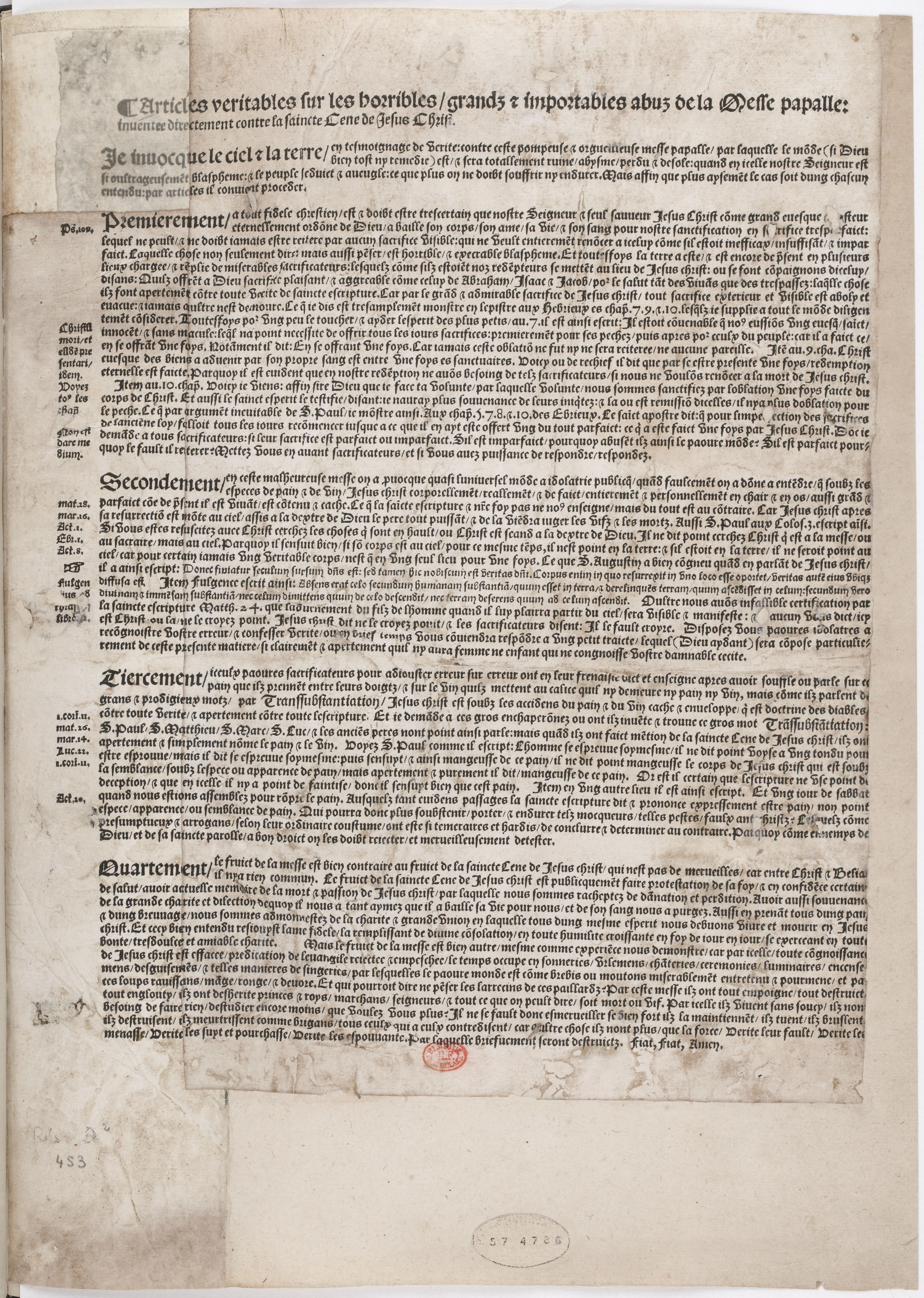

(4.8.2021) How about thinking the Renaissance in a whole new way? We may take away some of the beautiful princesses

and we may take away some of the warlords – replacing them with some lawyers, male and female: some copyright lawyers,

hardened and merciless as warlords, but also clear-eyed and well-informed as to the newest fashions and trends.

As far as I can see only Leonardo scholar Pietro C. Marani has briefly touched upon this sensitive issue (Marani 1998,

p. 23): how exactly did Leonardo da Vinci handle copyright? And yes, it is rather about him being copied, but we may also

think of him as copying somebody else, just theoretically (above picture bears the attribution: circle of Luini).

We may think that copyright is rather a modern concern, something that has to do with the age of mechanical reproducion.

No, this is not quite true. First of all: think of Dürer and of how enraged he was, when others sold copies of his

prints. And it is not about mechanical reproduction only anyway. Think of the cartoon, and of how a cartoon (having a

cartoon) does allow serial production, reproduction as well as new (edited) production; and here all the nuances are

coming in that, actually, we modern people do know and are familiar with. We only have to think of memes, appropriation

art, Warhol and the like. I am not allowed, by the way, to put a Picasso here, but I am allowed to put old masters here.

Because they are out of copyright. Two-dimensional reproductions of two-dimensional objects (not true, strictly speaking,

I have to say, developing now a lawyer stance) are allowed, as far as Renaissance paintings are concerned (it is different

with photos of architecture, for example).

And Marani actually pointed to Sforza Milan as also having rules (to break them). There was the guild of painters, and it

seems that rules, some formal, some informal did exist: one did agree on having copies made, but how to do them

technically? By sitting in front of a large altarpiece, taken down and having been brought to a workshop? In some cases

perhaps. But in other cases it must have been about the cartoon, the preparatory design; and the Renaissance is full of

cartoons. We have a Renaissance of the Cartoon, and this perspective, here, is our perspective: we may think the

Renaissance, for once, as a period not being full of spectacular colourful beauty, but rather as a period of less

spectacular, less imposing preparatory designs (being the nourishment of lawyers). This would help us to see several

things more clearly. For example: that beauty, illusionistic and colourful beauty was reached on a path that began with

sketches, preparatory designs and cartoons. But also, and this is our goal here, we may better understand the connoisseurial

problems that are posed by the existence of cartoons, the questions of copyright, but also the questions of authorship

as such (and of identifying authorship). Here comes the fourteenth episode of our New Salvator Mundi History, and we will focus on

three specific problems here.

One) In Search For Characteristic Traits

The above picture is interesting. It shows a painting in the Ambrosiana, a painting that is attributed to Bernardino

Luini. I am not familiar with its history of attribution, but this is not necessary here, since I only want to highlight

some questions. And the first question here is: do we recognize Bernardino Luini here, or do we only know that this picture

must be by Luini? What exactly are the pictorial elements, the characteristic traits that make us say that: this is by

Luini? Do such traits show here? Or other, perhaps material identifiers? Or is this attribution rather based on

documentary evidence (someone else, in the past, has said that…)?

Well, I said that I am not familiar with this picture’s history of attribution; but there is something else I know: I

know that Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo says that the cartoon of the Saint Anne (›Cartone della Santa Anna‹) by Leonardo

was with the painter Aurelio Luini (fourth son of Bernardino) in Milan. This could refer to the above shown cartoon,

the so-called Burlington House Cartoon, but it could also refer to another cartoon, perhaps, of which we don’t know.

At any rate: the question is raised: how could it be that, after Leonardo had died, Aurelio Luini was in the possession

of a cartoon by Leonardo? And now we come full circle: Could it be that the above shown picture is attributed to

Bernardino Luini, because we know that his son Aurelio was, perhaps after Bernardino had died, in the possession of a

cartoon, based on which this picture was made? And: Could it be that this picture shows rather Leonardesque traits than

Luinesque traits, which raises exactly the questions we actually want to highlight here: if a picture is being created on

the basis of a cartoon, to what degree we can, in such case, still recognize characteristic traits? Are such traits being

preserved? Perhaps in less important parts of the picture, as Morelli had proposed, in background landscapes or in

details such as ear lobes? Or do we have to concede: if a picture, perhaps a Salvator Mundi picture, is being created on

the basis of a cartoon, it becomes more difficult, and it could even become impossible to still identify characteristic

traits, exclusively characteristic traits of its actual maker. While we still may be able to identify the basic idea of

its inventor.

Brief: we may be able to identify the song, but not the singer. Which is only tragic, if we ask for the singer, the

actual interpreter, and not the song. But this analogy is perhaps a wrong one, because it is about the voice. And it is

exactly the voice we may be able to identify here (but we do not hear a voice). So let’s say: we may recognize the lute

tune, but not the luthenist (or the lute). If yet the luthenist is what we are asking for. If we do know of the danger of

confusing the composer with its interpreter, this may not cause a problem. But in Leonardo studies we face the problem

that the luthenist is always, necessarily and at every moment in time: Leonardo (as I have defined the first and most

problematic law of Leonardo attribution, the first law of ubiquitous, but for mysterious reasons always unseen and

ignored confirmation bias).

Two) Facing Multiple Cartoons and Complex Chronologies

Leonardo da Vinci has left many notes on painting that have been transmitted to us in various ways. We do know him, on

some level, as a teacher. But one thing we do not seem to know: if his pupils started with drawing – did Leonardo have

his pupils also copy cartoons? Maybe he did not have them in the early stage of their instruction, but what if a pupil

or collaborator, who had been involved in a particular project, a painting – did Leonardo perhaps allow that such cartoon

that had been the basis for a painting was copied by his collaborator afterwards? So that the collaborator could, also

much later, draw on such tools and develop his own ideas further from there?

Unfortunately we don’t know such details, but again the question is raised: how to deal with the complexity of cartoons

multiplying, and how to deal with the complex chronologies (and geographies) that are possible, if cartoons are

multiplying. We may be confronted with a highly complex tradition of a motiv, and hence we have to develop an equally

complex philology of the cartoon.

I am speaking, of course, indirectly of the Salvator Mundi design here, but the case we had been discussing in our last

(thirteenth) episode of this New Salvator Mundi History, is equally interesting and somewhat less complex:

We had seen that there are two versions of the portrait of a noblewoman, and that we may assume that a cartoon existed,

upon which these two versions had been created. This case seems simple, but even if only a cartoon and two versions of a

painting do exist, the chronologies possible can become very complex.

We could assume that one version had been based on the original cartoon, and one on the copy of a cartoon, and even if it

had been created on the basis of an original cartoon, such production could have happened much later. As we have seen,

tools pass from one painter to another, from one workshop to another, from father to son perhaps, and if a cartoon was

produced at some moment in time, this does not necessarily mean that a corresponding painting was created in the same

period. As we had seen, it could also be that a corresponding painting may show the whole biography of a painter, while

the original cartoon shows him in one particular and rather early moment in his career. If such complexity is only seen

in terms of original painting and assumed copies, we would impose a dichotomous model of interpretation on a complex

reality, an overly simplified model that simply is not adequate to interpret the Renaissance of the cartoon. And we do

know for certain that at least one, and in all probability rather many cartoons of the Salvator Mundi design did exist.

We will attempt to develop an adequate philology of the cartoon in our next episode to come.

Three) Various Hands May Handle Copyright in Various Ways

Looking at the above picture by Luini (in the Louvre) we may think that, for this picture Leonardo da Vinci might not

have been entitled to claim his copyright. But again this is not as simple as it seems: this Christ is in movement, and

as the blessing hands seems to be in movement, also the body of Christ seems in movement of an analogous kind. The same

scheme, the representation of a figure in a multiple and seemingly circular movement, we find also in pictures by

Giampietrino, with less robust representations of Christ, and we may ask, if, in the picture shown above, we see a

robustly Luinesque interpretation of a Leonardesque idea that we may also find in Giampietrino.

At any rate we are entering the world of post-1519-Leonardismo, and as interesting as is the question of how Leonardo did

handle copyright, is the question of how the Leonardeschi did. After 1519, among themselves, thinking of their common

master, and perhaps not all agreeing on how copyright should be handled. The central figure, again is Melzi, and

unfortunately we have little direct information as to how Melzi did handle copyright, as the person who had control over

all the cartoons left, because Leonardo had bequeathed everything, and we have to add: also the cartoons – everything

that had to do with Leonardo’s call and profession as a painter, to Melzi. How exactly did Melzi handle that? If only we

would know.

But we have indirect information, ambivalent information that has to be deciphered and interpreted, as has the

information transmitted to us by Lomazzo, saying that Aurelio Luini was in the possession of a cartoon by Leonardo (did

he get it from Melzi?). We can assume that his fellow-Leonardeschi knocked at Melzi’s door, sooner or later, and we may

also assume that, having lost their master, after 1519 they somehow might have got together to commemorate. Perhaps this

did not happen at all, perhaps they were all in conflict over Leonardo’s heritage, if only we would know, but we still

can see that designs by Leonardo do reappear in what has been called ›belated Leonardismo‹. If the picture shown above on

the right had been attributed earlier to one of the Spanish Leonardeschi, this picture (in Berlin) has now also been

attributed to Girolamo Figino, who can be seen as a pupil of Melzi. Perhaps future scholarship will find out if he was

and in what way (how long and to what consequence and so on), but for the moment we are left with the crucial question of

how Francesco Melzi, perhaps commemorating Leonardo, perhaps not, did handle copyright. Copyright in a sense of

interpreting informal, perhaps also formal rules of how one was to deal with the ideas of other people.

(Below the more refined blessing Christ by Giampietrino in the Pushkin Museum; Wilhelm Suida had another picture of a

Blessing Christ attributed to Giampietrino that is, in his robustness, somewhat more closer to the Luini above; it is No.

147 in Suida, Leonardo und sein Kreis, Munich 1929, p. 86); below on the right again Luini (picture:

fondazione.zeri.unibo.it).

Selected literature:

Pietro C. Marani, The Question of Leonardo’s Bottega: Practices and the Transmission of Leonardo’s Ideas

on Art and Painting, in: Francesco Porzio (ed.), Legacy of Leonardo. Painters in Lombary 1490-1530,

Milan 1998, p. 9-37

1495: At around this date Leonardo da Vinci is supposed to have begun The Last Supper. Giampietrino is documented as an active painter.

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

Giampietrino’s Kneeling Leda is just another example of a painting having been created on the basis of a cartoon (see Leonardo biography by Charles Nicholl, German edition, p. 541)

See also the episodes 1 to 13 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS