M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM A Salvator Mundi Provenance |

See also:

Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

Some Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts

Some Salvator Mundi Variations

How To Tell Leonardo From Luini

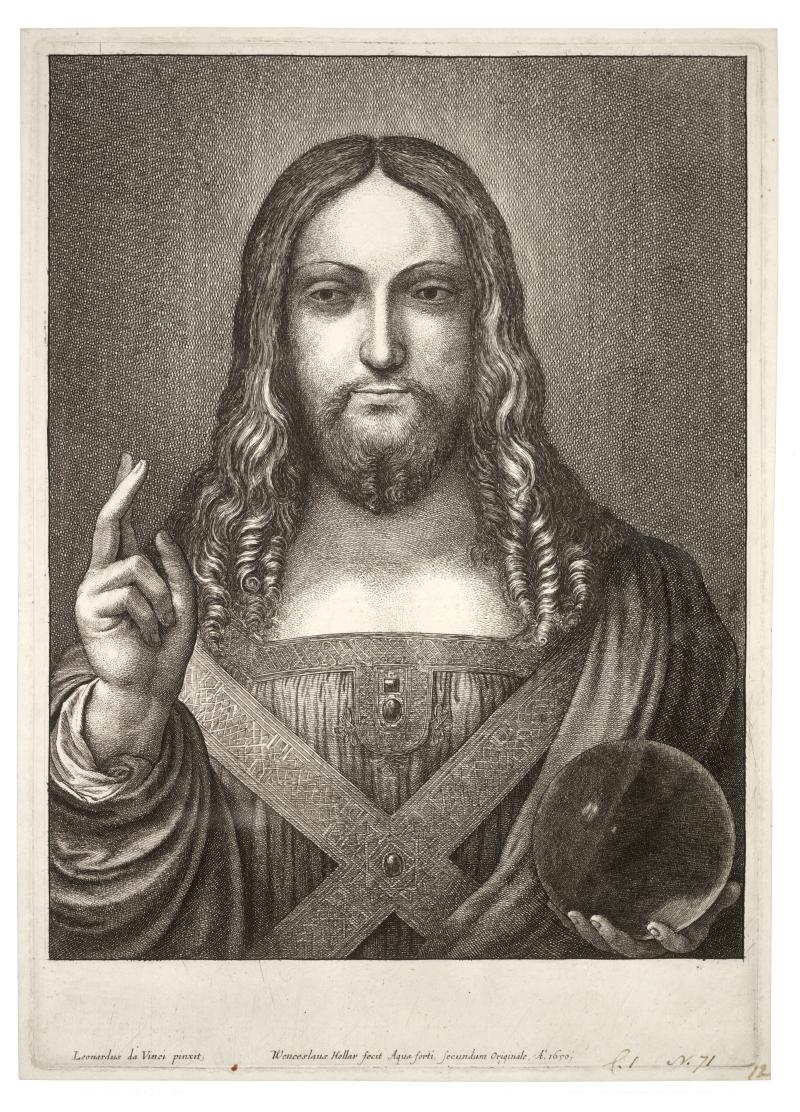

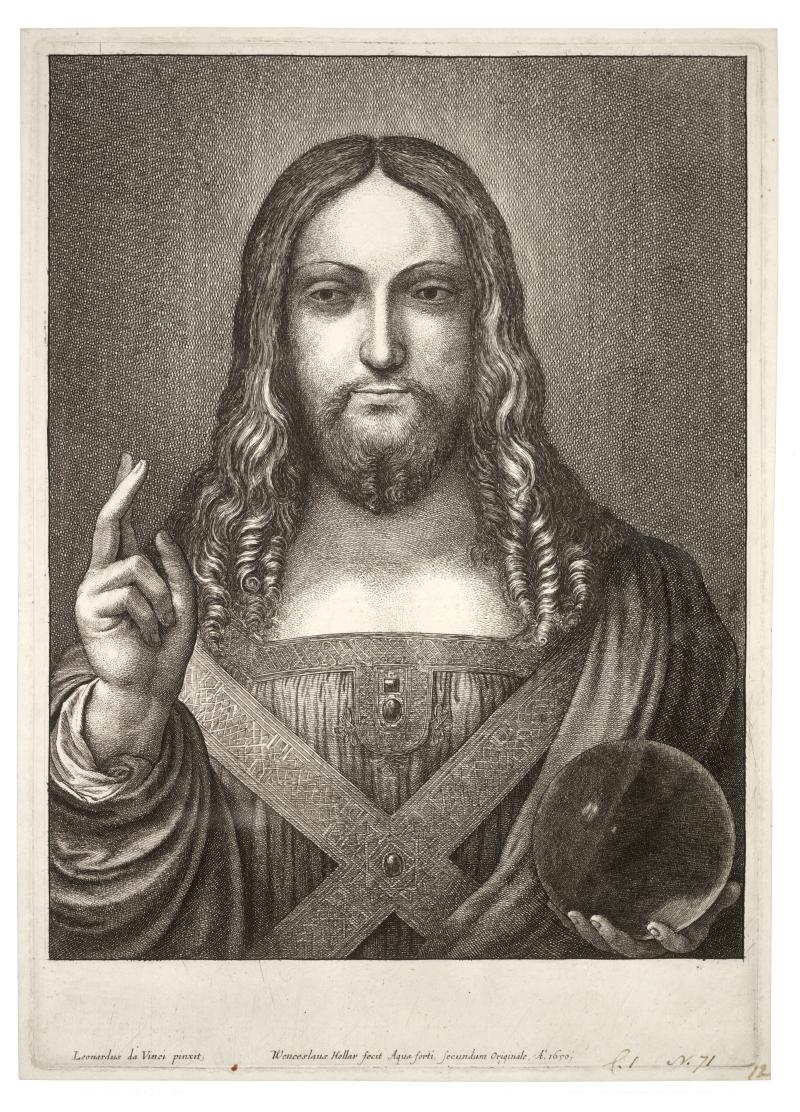

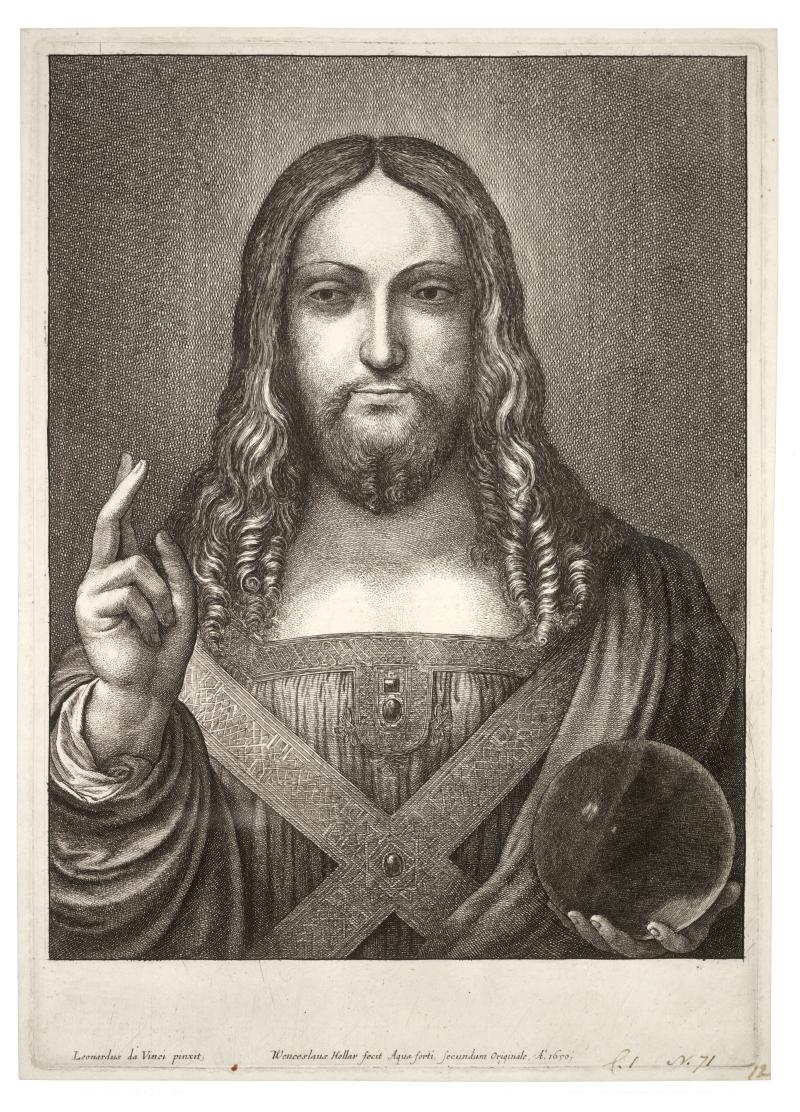

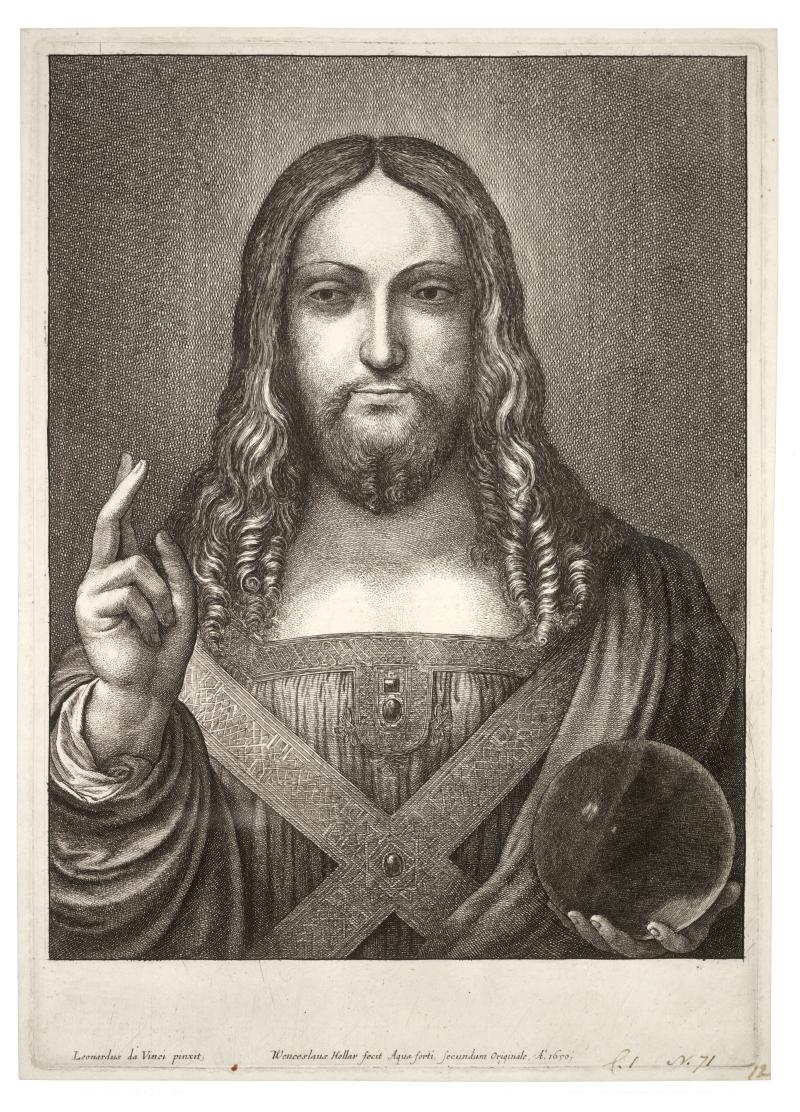

A SALVATOR MUNDI PROVENANCE

This is meant to offer a historical frame of reference

for Salvator Mundi provenance studies in general.

Here on the left we follow the story of just one version;

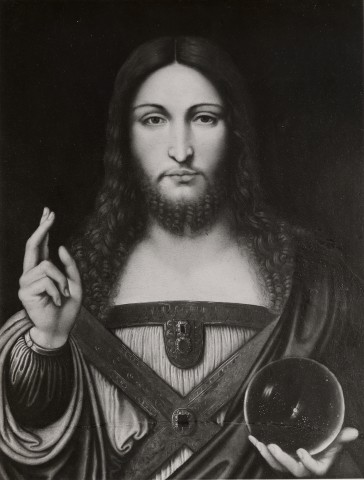

the one version (picture above) now in the Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

On the right we have assembled dates as to the history

of the whole Salvator Mundi-family (whose ›members‹

in some way or the other have been associated with an assumed

Leonardo da Vinci-prototype, in what form this prototype may have existed

or not have existed at all.

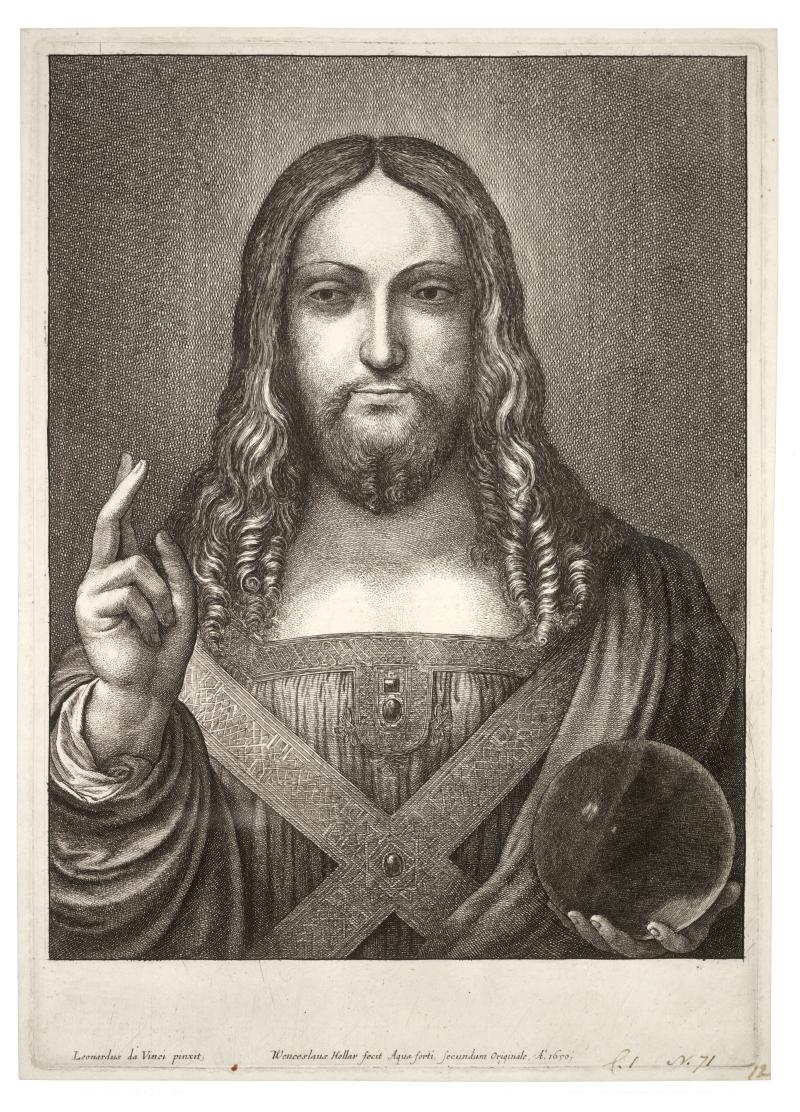

This story begins with my stumbling over an etching in the 1822

catalogue of the pictures at Leigh Court near Bristol (below on the left):

Also a Rio de Janeiro version is known (Museu Nacional de Belas Artes,

apparently from the collection of Joachim Lebreton):

However I linked this etching to the Salvator Mundi version now at Houston

and tried to confirm the hypothesis that the Houston picture is the one

once at Leigh Court near Bristol (picture below: leighcourt.co.uk).

And here is what I could put together as to a provenance:

At the end of the 18th century the Leigh Court picture was, according to

the 1822 catalogue, purchased at Paris by Mr. Bryan;

brought to England; soon after disposed to Rev. Mr. Hamilton,

brother of Sir William Hamilton and uncle of the Earl of Warwick;

sold (with five other pictures) to Mr. Troward for six thousand guineas;

referred to as Creator Mundi – and alternatively as Salvator Mundi –

and being regarded as a work by Leonardo da Vinci;

No. 38 of the Leigh Court collection (Sir William Miles);

shown in the library room of Leigh Court near Bristol,

seat of Sir William Miles, and later of Sir Philip Miles,

who seems to have taken the picture also to his Bristol residence.

1818: exhibited at the British Institution.

1822: Catalogue of the Leigh Court collection (Sir Philip John Miles)

by John Young (with etchings).

1835-1852: Georg Kaspar Nagler (Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon)

associates the picture with two other Salvator Mundi versions

in British collections (Earl of Leicester, Holkham Hall; this version still at place;

and Mr. W.-G. Coesvelt, London; this version now in the Hermitage of St. Petersburg as by Giampetrino)

and suggests that all three versions might have been derived of a picture by Luini

(below the Hermitage Giampietrino with Christ holding a triangle, symbol of the trinity;

several other versions/derivatives of this composition are known).

1844: the above shown engraving ›After Leonardo da Vinci‹ is published

(picture: royalcollection.org.uk)

1851: according to testimonies visitors of Leigh Court are allowed to see

the Philip Miles owned picture.

1875: not shown in a Royal Academy exhibition (but missed

by a critic of The Saturday Review, who also mentions

that some believe the picture to be by Boltraffio); Lady Eastlake is

questioned about a supposed Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci.

1877: exhibited at Burlington House.

1883 (August): the collection of Sir Philip Miles is seen

by Jean Paul Richter who believes the picture to be a 17th century work

and writes accordingly to Giovanni Morelli.

1884: Leigh Court Sale (as by Leonardo da Vinci);

bought by the London based art dealer Lesser Lesser.

[possibly a gap in provenance; if it can be filled, our hypothesis would be confirmed;

if not, it has to be revised; the Rio picture, however, cannot be identical

with the Leigh Court picture, since Lebrun already had emigrated to Brasil,

before even the etching after the Leigh Court picture was made]

Mr. Harris Masterson III (1914-1997) and Mrs. Caroll Sterling Masterson.

Today location: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Rienzi collection

(gift by Mr. and Mrs. Harris Masterson III.),

(as by a ›Flemish Artist‹, third quarter of 16th century).

(Picture: goldennumber.net)

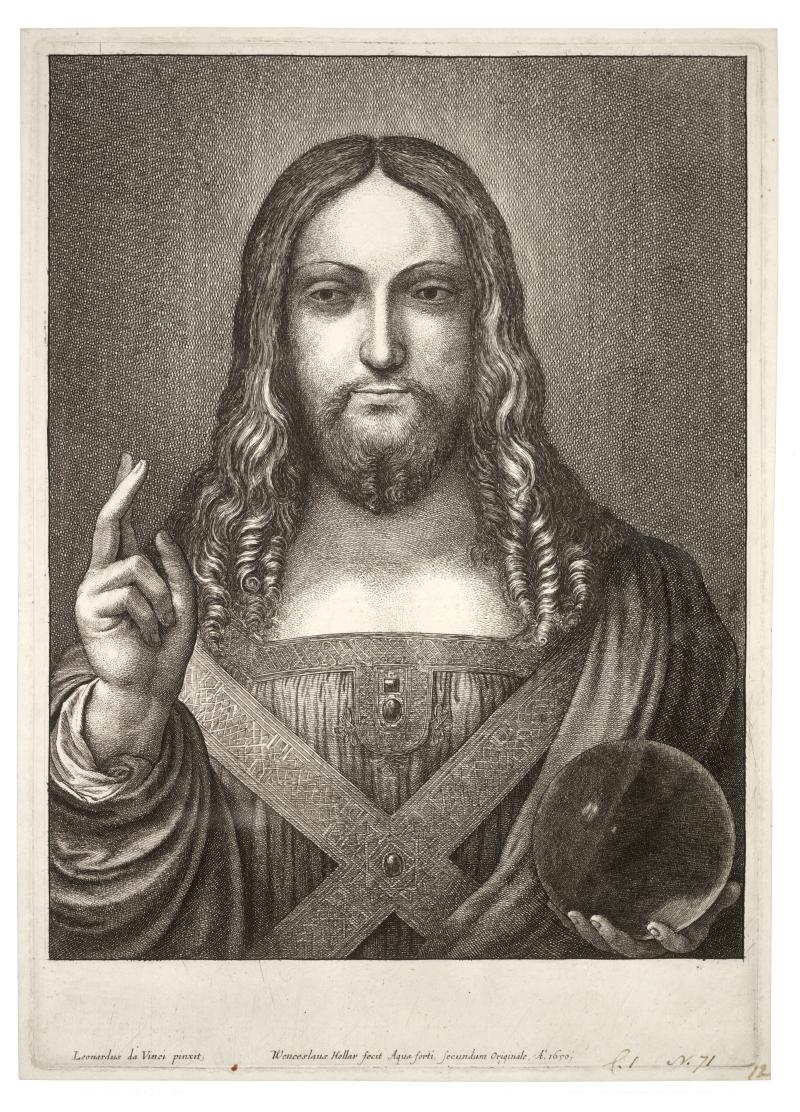

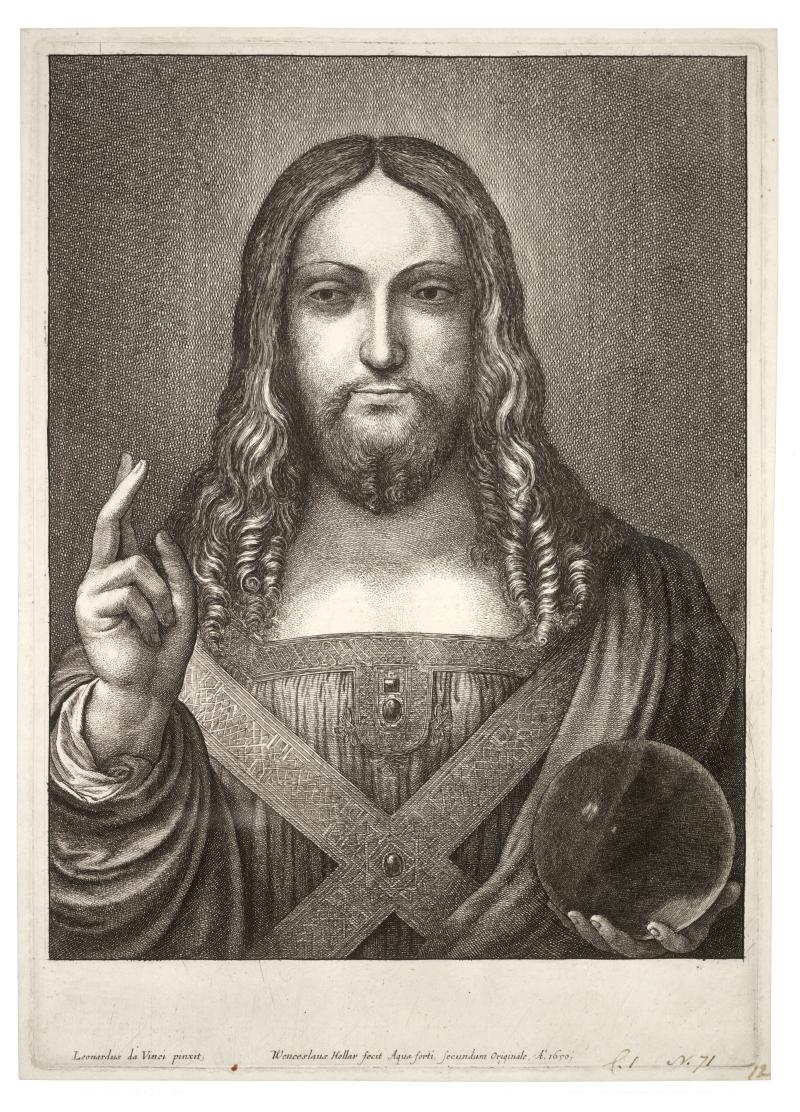

1650: Due to the above etching by Wenceslaus Hollar we face two everlasting questions: firstly, after which painting was it made? and: was the painting it was made after indeed, as the etching does say, a work by Leonardo da Vinci? This said, it might be, at least theoretically, that this etching was reproducing a picture not-made by Leonardo, and: that no actual prototype in terms of a finished painting by Leonardo did in fact exist (any more), even if the painting the etching was reproducing, indeed can be identified (see also below, sub 1915).

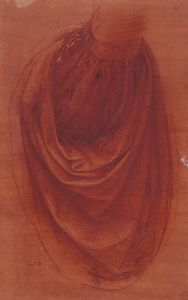

Two sheets with drapery studies from Windsor (pictures: lucyvivante.net) are to be considered as the other crucial reference works of any Salvator Mundi debate:

1651-1763: A Salvator Mundi of the Royal Collection which is ascribed to Leonardo da Vinci (and which is probably the picture after which Hollar had worked) can be followed from the Royal collection to a 1763 sale (more details here).

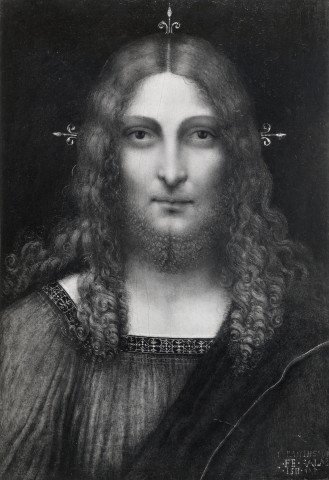

Early 19th century: three Salvator Mundi versions in English collections, all of them linked with Leonardo, are known (see texts on the left; none of these are discussed by Heydenreich in 1964); moreoever: another version is in possession of the Earl of Yarborough (picture below: fondazionezeri.unibo.it; note here, as in chosen other versions, the also crucial Ω-shape (›omega shape‹; picture below: via.lib.harvard.edu) in the drapery, and compare with the one windsor sheet above on the right; present location of the picture is unknown).

1869: John Ruskin, The Queen of the Air [with epoch-making praisal of Bernardino Luini].

1889: a Salvator Mundi (now ascribed to Giampietrino) is given to the Detroit Institute of Art (picture: dia.org):

1891: two Salvator Mundi versions, both from the collection of Giovanni Morelli and one of them depicting a young Christ, come to the Accademia Carrara of Bergamo (pictures: lombardiabeniculturali.it ; lacarrara.it):

1898: ›Masters of the Milanese and allied schools of Lombardy‹-exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club (with catalogue)

1904: as a work by Quentin Matsys the later Zurich Salvator Mundi (see below) turns up at a sale at Cologne (Vente Bourgeois Frères at Heberle-Lempertz)

1907: Bernard Berenson, North Italian Painters of the Renaissance [with epoch-making dismissal of the Leonardeschi].

1915: Francesco Malaguzzi Valeri (La corte di Lodovico il Moro, vol. 2 (Bramante e Leonardo da Vinci), p. 558) points to a still all too little known 18th century source: Padre Vincenzo Monti, librarian of Santa Maria delle Grazie of Milan, speaks of a lunette painting done by Leonardo above a door in Santa Maria delle Grazie, a painting depicting the Saviour, and a painting which, according to this source, had been destroyed in 1603, due to an enlarging of this door. It may be that Salvator Mundi studies in general have neglected this source, blinded by the existence of the Hollar etching. Since it may also be that, if this lunette in fact did exist (and perhaps also a cartoon), all other derivatives might have been done by Leonardo pupils, which means that the whole Leonardesque Salvator Mundi family, including the model for the Hollar etching, might stem from this lost lunette. Italian scholars (P. C. Marani; C. Pedretti) have occasionally mentioned Monti’s testimony, his Catalogus, but Santa Maria delle Grazie has not especially been in focus of Salvator Mundi studies, all the more, of course, since the existence of minor works by Leonardo might have been outshadowed by the Last Supper.

1929: Wilhelm Suida, Leonardo und sein Kreis (see also for the Italian subgroup of Salvator Mundi versions).

1964: ![]() Ludwig H. Heydenreich (picture: faz.de), Leonardo’s »Salvator Mundi« (Raccolta Vinciana, Fasc. XX; without mentioning, by the way, of the Monti testimony).

Ludwig H. Heydenreich (picture: faz.de), Leonardo’s »Salvator Mundi« (Raccolta Vinciana, Fasc. XX; without mentioning, by the way, of the Monti testimony).

recalls also a Warsaw version:

and also a Zurich version (then: Stark collection; present location unknown; picture: DS, after Raccolta Vinciana):

1982: Joanne Snow-Smith, The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo da Vinci. And we may speak of a end of 1970s and 1980s hypothesis that this is the painting the Hollar etching was made after (Salvator Mundi ex De Ganay; dismissed, by the way, by Berenson as the work of an inferior pupil of Leonardo; addition as of November 2017: Italian media have more than once assumed that Carlo Pedretti has been supporting the attribution of this version to Leonardo; Christie’s, in 2017, lays weight on the claim that Pedretti, as they believe, never asserted this; in 2011 Pedretti referred to the de Ganay picture as ›probably [by] Giampietrino‹ and dismissed the 21st century hypothesis (see further below), based on mere judgment by eye:

21st century: the 21st century hypothesis that this is the painting the Hollar etching was made after (Salvator Mundi ex Cook; addition as by November 12, 2017: as is, largely, the serious testing of alternative hypotheses; which means: as long as the former hypotheses – «by Luini», «by a follower of Boltraffio», «by Boltraffio», as well as the more recent hypotheses «(perhaps) by Boltraffio and Leonardo da Vinci» and «perhaps by workshop and Leonardo da Vinci (?)» – have not seriously been tested, this is not exactly an example of state-of-the-art scholarship, but a now worldwidely known example of biased research; updates forthcoming; Pietro C. Marani has now expressed his opinion more specifically in an interview: according to him the ›better parts‹ are by Leonardo, which means: the parts around the face; not the face itself, though; thus: a ›faceless‹ Leonardo…, according to this one expert; others seem to disagree in this very point; thus we actually cannot speak of a ›consensus of experts‹:

Some open questions that remain:

– Why does the Christ of the painting show beardless, if it is supposed to be the model for the Hollar etching

(some seem to assume that the paint layers of the face are intact, and some don’t)?

– Is exclusive optical knowledge absent or present in the painting?

– Is the lapis lazuli used for the robe of »extraordinarily fine quality« (Nica Rieppi, as quoted by Time)

or »rather coarse and contains particles of quartz« (restorer Dianne Dwyer Modestini; online brochure as provided by Christie’s, p. 71;

and Modestini goes on to say: »I have wondered whether it was made by merely crushing the mineral rather

than being the product of the elaborate process of extraction used in Tuscany.«)?

- Are the pentimenti to be interpreted as more than mere corrections or as mere corrections?

– Can it be excluded that the picture mentioned in the inventories of English Royal collections

is the painting of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (see below)?

– Why is the ›omega-shape‹ in the drapery, to be found in the preparatory sketches,

lacking in the New York painting, while it does show in other versions, supposedly derived from or later as the New York version?

– How do the experts who do not mention the Vincenzo Monti-testimony interpret it?

And finally a version (picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it), derived from…?

(According to A. Vezzosi on canvas and in a private collection; angels added in 1843; in 1844 this work was donated to the Versailles Cathedral by archevêque Louis Blanquart de Bailleul)

See also (especially as to ›biased research‹):

The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

A SALVATOR MUNDI IN THREE REVOLUTIONS

Why are there Leonardeschi at all, Leonardesque painters, that is?

One answer might be that the influence of Leonardo da Vinci on certain painters,

certain painters with a less strong artistic personaliy,

was so strong that these painters could not but imitate Leonardos’s style

and follow his ideas.

But with a grain of salt we may also say that there are Leonardesque painters,

because Leonardo da Vinci employed doubles.

But, good gracious, why would he have done that?

Well, for example because Leonardo might have felt saying ›I have so many other things to do,

please leave me alone!‹, for example if Isabella d’Este again felt like pestering him,

because she wanted him to produce something for her studiolo.

And this is why Leonardo might have produced a drawing and – this is our point here –

might have agreed with a talented follower of his (with less strong an artistic personality)

to actually produce a painting in his name. Or even – why not? – under Leonardo’s own name.

And this is what we mean by saying doubles. His follower might have been happy,

and Leonardo himself might have been able to turn to other things that interested him more.

This, of course, is said with a grain of salt. But fact is that almost all

productions of Leonardesque painters, at some point or other,

including the above shown Salvator Mundi from the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Art,

went under Leonardo’s name (and this painting, now ascribed to Giampietrino – picture: Sailko –

might even have come from the art collection of the Gonzaga of Mantua, which is why

we felt entitled to mention Isabella d’Este’s name here; picture below on the right: wikiart.org).

But be it as it may (and of course there are Leonardeschi of various kinds

and also manyfolded reasons why there are Leonardeschi)

and our aim here is something else anyway.

We would like to trace back – and this on the right side – the biography of the above painting,

which is a biography that leads us through the history of – at least –

three revolutionary eras.

And this is particularly interesting, because Renaissance art is (perhaps all too) often

taken out of context and enjoyed for simply being harmonious and beautiful,

while it tends to be rather ignored that being harmonious and beautiful might mean something

in times that are full of tensions (like revolutionary eras, and like also

the very torn era of the Renaissance),

and something else in times that are saturated and know little of what it means to have something

harmonious and beautiful to look at in times of uncertainty, or even terror and civil war.

And this Salvator Mundi’s history might be fit to remind exactly this: the meaning of context,

the meaning of spiritual paintings (in various historical times), and the meaning of beauty,

in relation of context. And beautiful an example this is as well to show

that tracing back provenance does not only mean to trace back the context of social history,

but also the history of perception, various perceptions, as various as social context can be.

A Revolutionary Past – Provenance Studies as Revolutionary History

I. From the age of Charles I to the Glorious Revolution:

»Provenance: in the collection of King Charles I of England in the 17th century; it had possibly been in the Gonzaga Gallery collection in Mantua prior to that, which Charles I acquired before 1627; […].« (Source: Pushkin Museum: italian-art.ru; picture: italian-art.ru)

II. The French Revolution:

»[…] as legend has it, the painting was in the Louis XVI Gallery which was plundered during the French Revolution; […]«

III. The Russian Revolution(s):

»[…] in the Mosolov collection (Moscow) in the 19th century; donated by N. S. Mosolov to the Rumyantsev Museum in 1914; in the Pushkin Museum since 1924.«

»In the Mosolov collection this was considered to be a work by Leonardo da Vinci; it was attributed to Giampietrino by N. I. Romanov.«

THE ITALIAN SUBGROUP OF LEONARDESQUE SALVATOR MUNDI PAINTINGS

Regalata da Papa Paolo V al nepote Scipione Borghese in 1611 as

– no surprise – a painting by Leonardo da Vinci:

the Galleria Borghese Salvator Mundi, now ascribed to Marco d’Oggiono

(picture: tumblr.com).

No picture is available (for the moment) of the Salvator Mundi

by Agostino da Lodi (in a private collection),

showing a young (and at the same time old-looking) Christ.

No picture either of a Salvator Mundi that was seen in the (probably early 1960s)

Milan art trade and endorsed as a work by Leonardo da Vinci by Coletti

(mentioned by Angela Ottino Della Chiesa, Wissenschaftlicher Anhang,

in: Das gemalte Gesamtwerk von Leonardo da Vinci, Milan 1967, p. 112).

---------

As already mentioned above: 1891: two Salvator Mundi versions, both from the collection of Giovanni Morelli

and one of them depicting a young Christ, come to the Accademia Carrara of Bergamo

(pictures: lombardiabeniculturali.it ; lacarrara.it):

---------

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it):

Private collection (ex Trivulzio; picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it;

Zeri: »›Mâitre de la Vierge aux Balances‹ (Salaino)«):

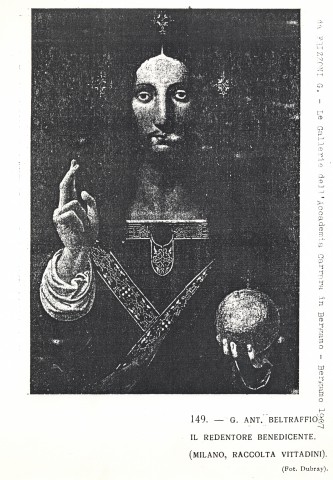

Arcore near Monza (?): (ex Vittadini; picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it):

Naples, San Domenico Maggiore, Cappella Muscettola (picture: pinterest.com;

note the above mentioned ›omega shape‹):

Further Comparisons

Above: Antwerp: Quentin Massys (Matsys), Christus Salvator Mundi

(picture: Riopelle).

Might this be the Salvator Mundi seen by Winckelmann

in the Liechtenstein collection?

(Another version at Christie’s in 2014, see here)

Representing the (earlier and contemporary) Venetian subgroup

we choose Marco Basaiti (picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it)

›Lombard follower of Leonardo da Vinci‹. – At auction at Sotheby’s in 2016:

From the estate of Ludwig Mond

(but not mentioned in the Jean Paul Richter catalogue of the Mond collection;

which makes us assume: probably once belonging to Frida Mond,

and as such not regarded (by Richter) as being part of the Mond collection)

Now Pinacoteca Ambrosiana: the Head of Christ (?),

according to the signature, by Salai (picture: ilgiornaledellarte.com ;

fondazionezeri.unibo.it).

No picture available of: Albrecht Dürer, Salvator Mundi, formerly Kunsthalle Bremen (but see it here).

See also:

Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

Some Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts

Some Salvator Mundi Variations

How To Tell Leonardo From Luini

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS