M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

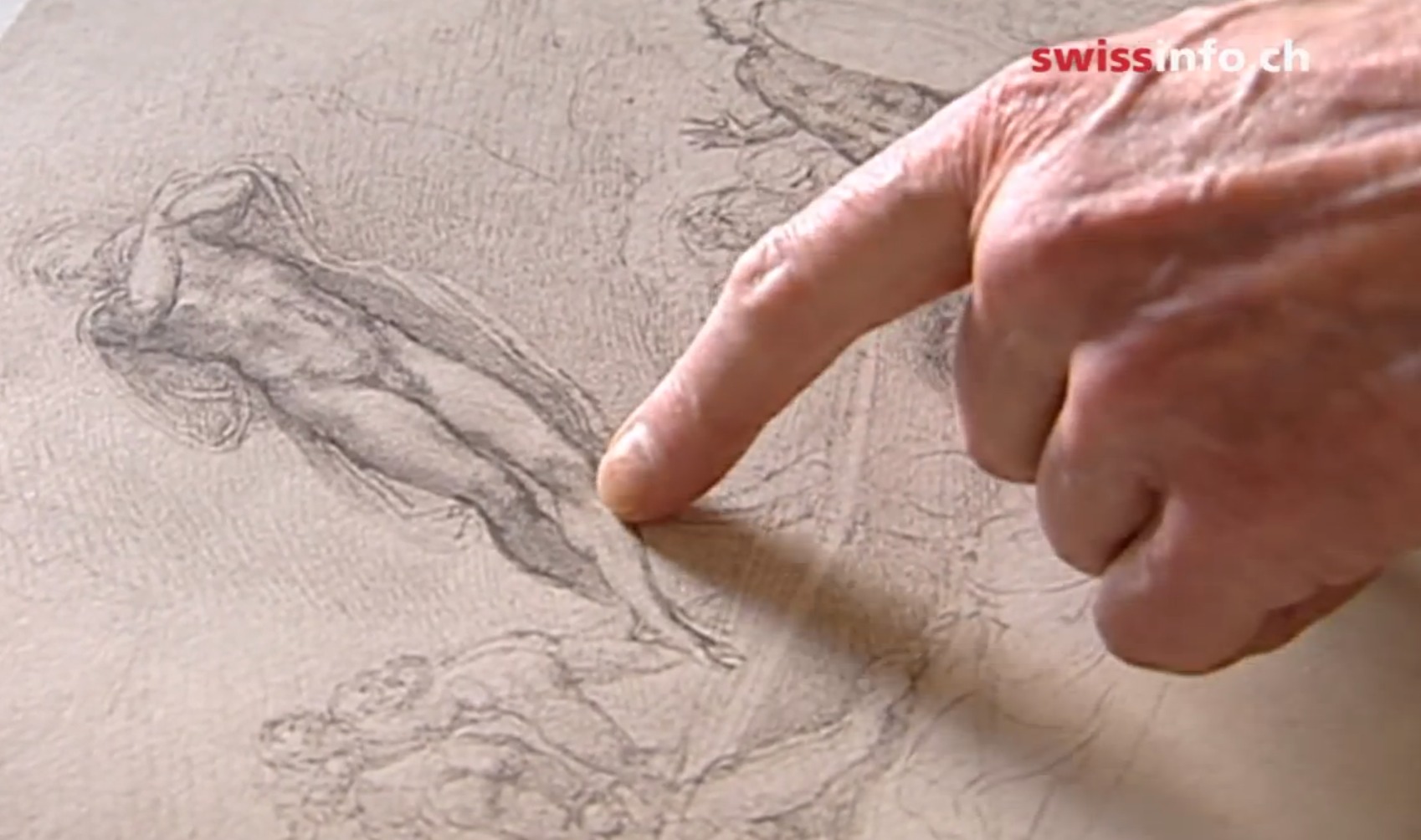

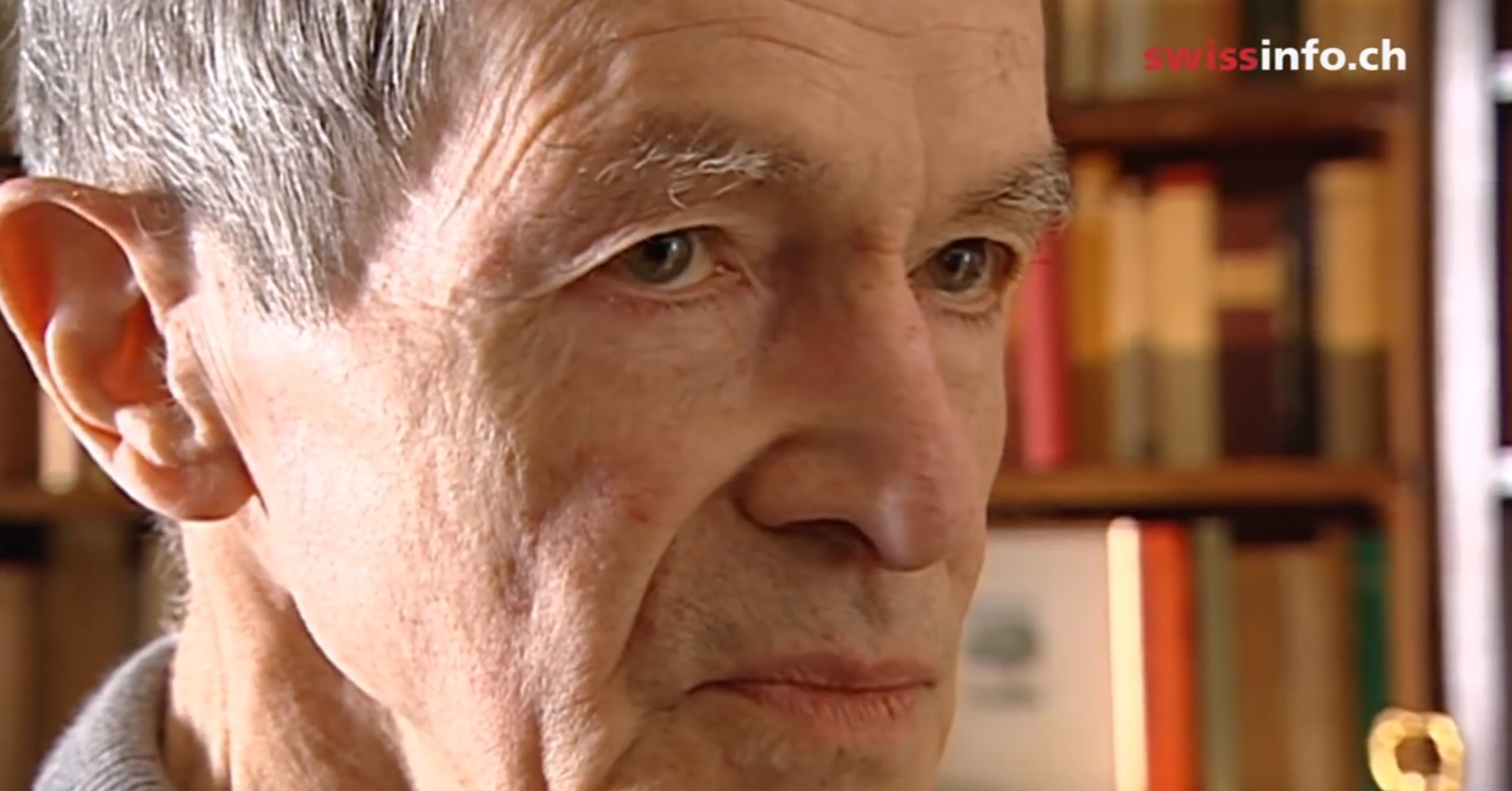

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM  (Picture: cbc.ca; bg picture: yalepress.yale.edu) Alexander Perrig and the Planet of Zeichnungswissenschaft |

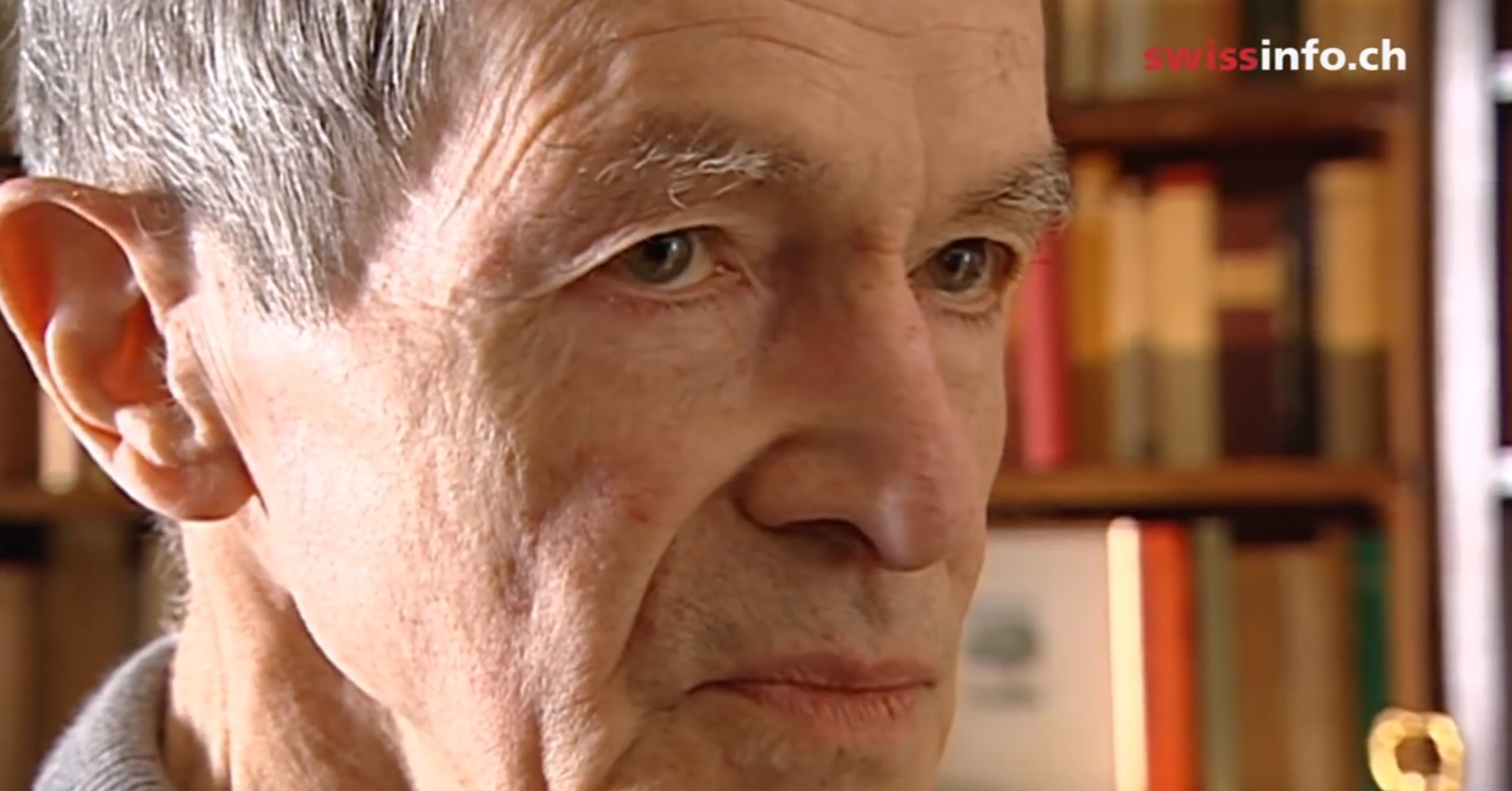

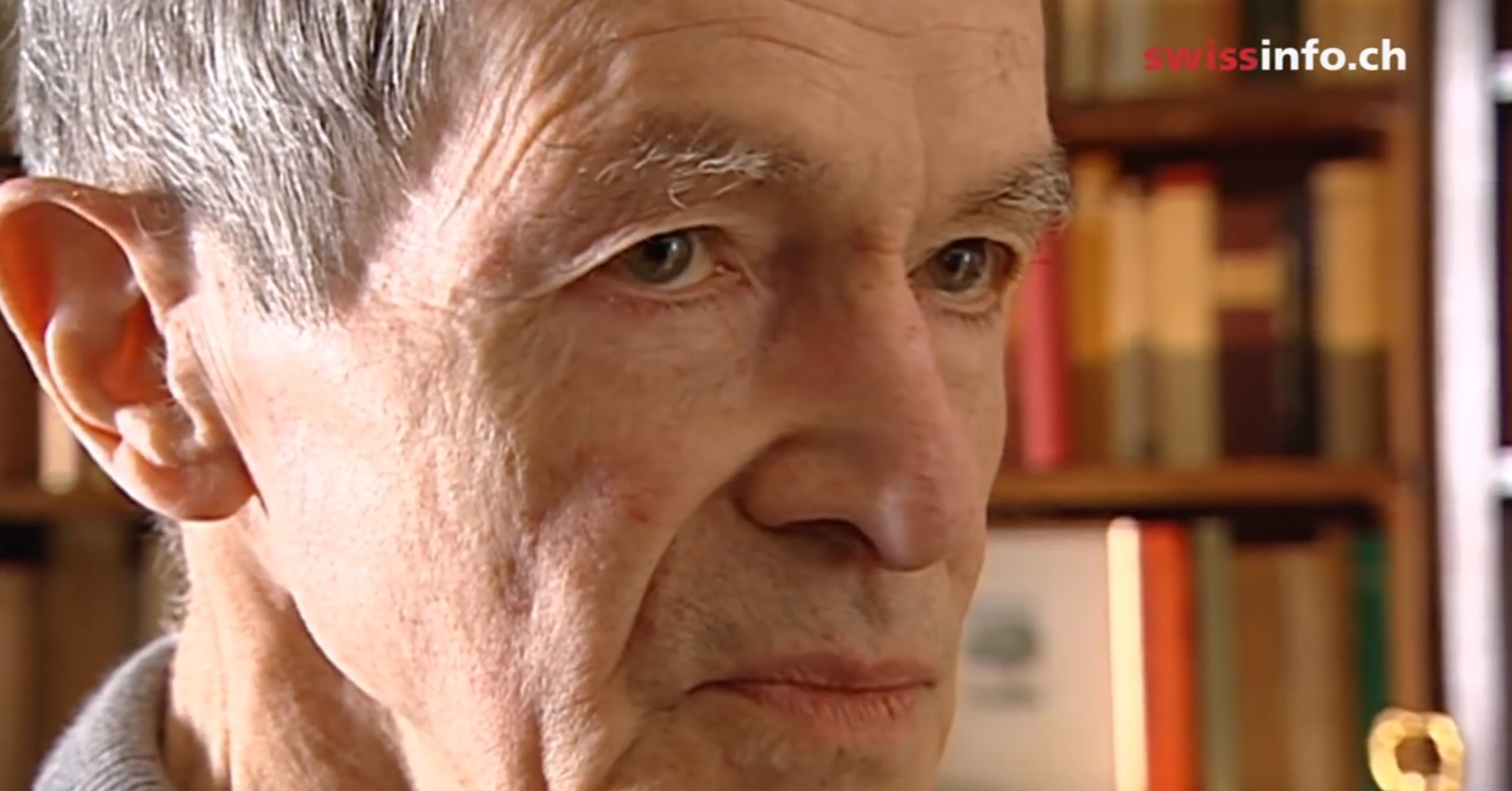

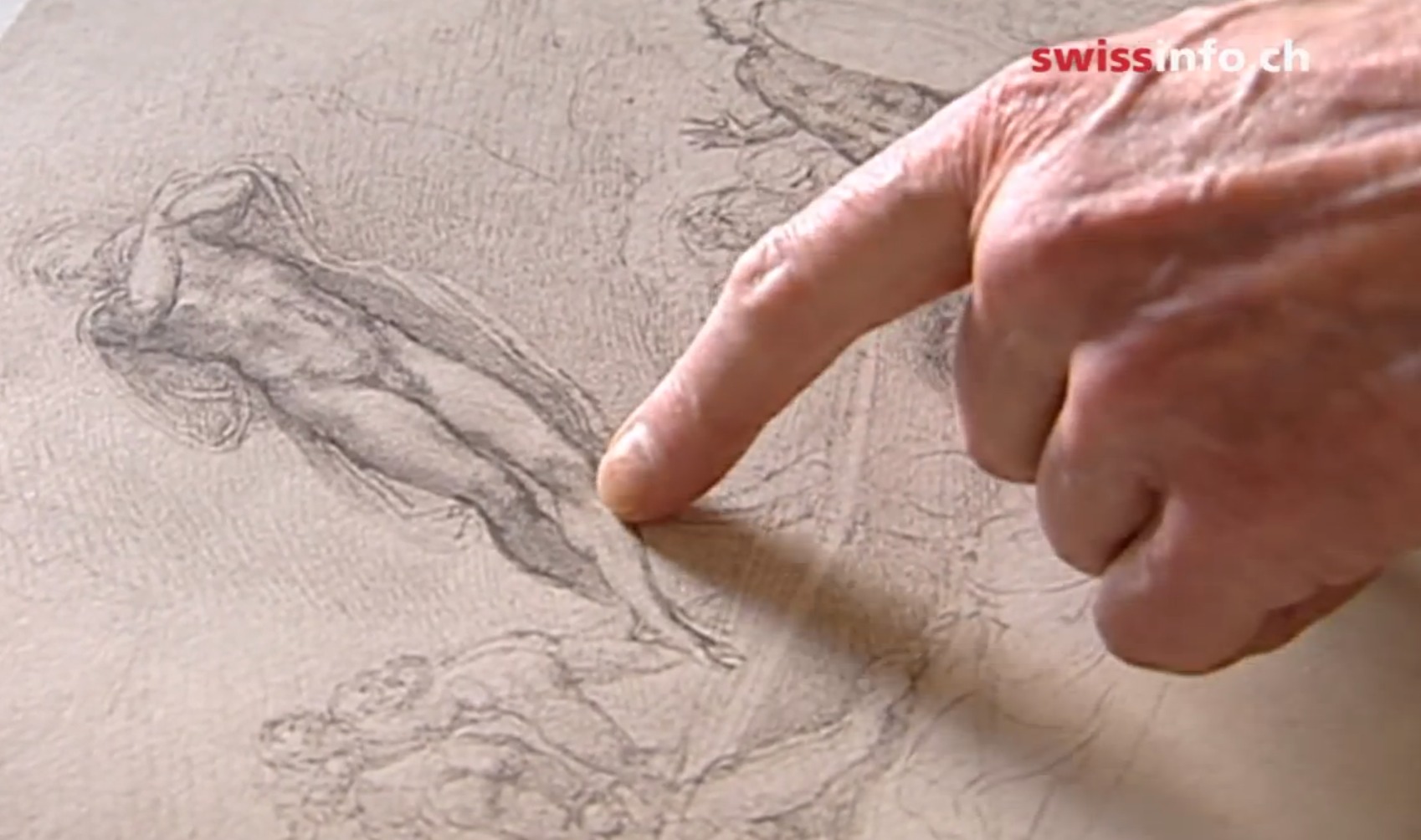

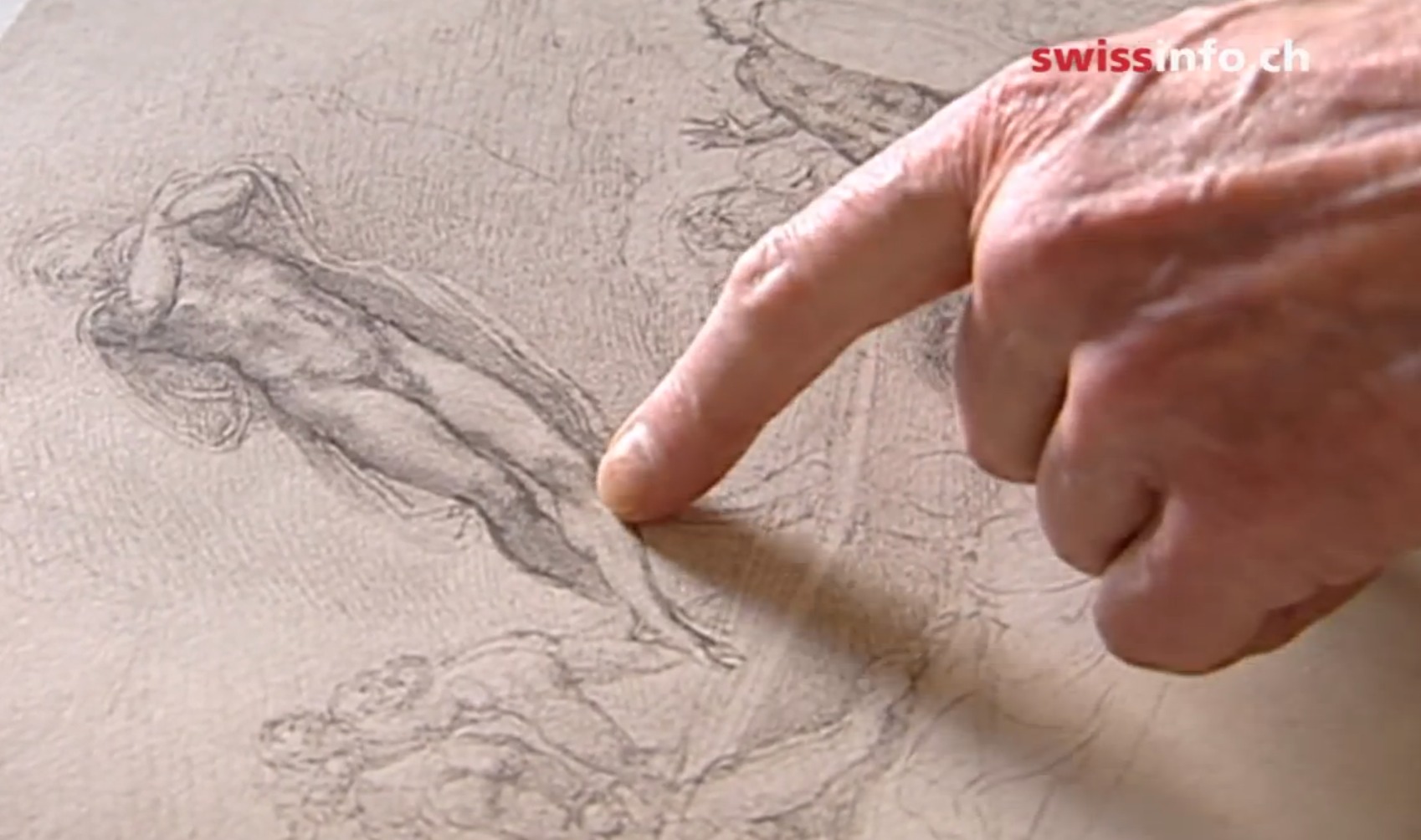

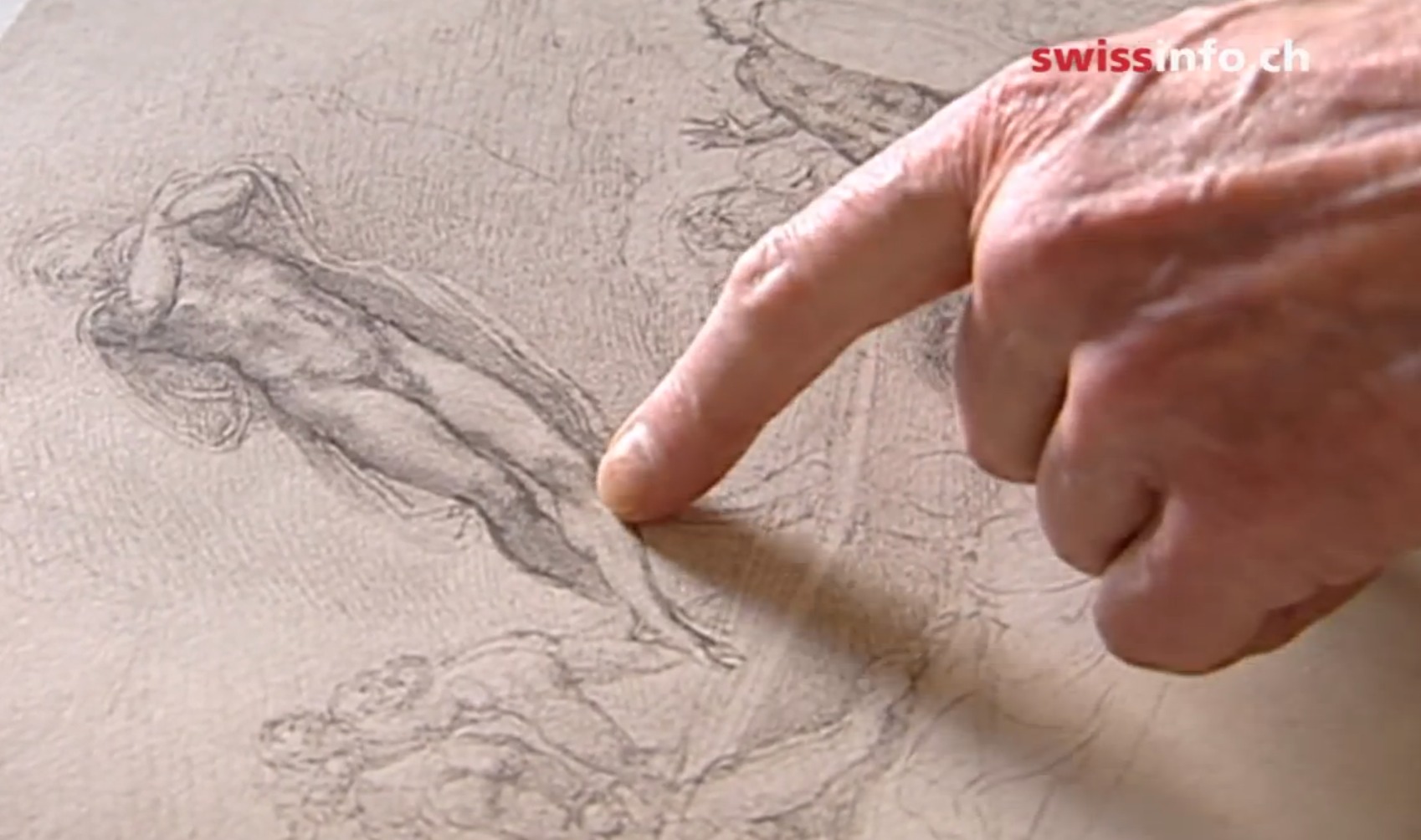

I believe it to be necessary to dedicate a platform to Swiss art historian Alexander Perrig’s attempt to renew (or even to establish) Zeichnungswissenschaft. And this for two reasons: It has become a historic struggle – Perrig’s challenging of connoisseurship. And connoisseurship means here (for the moment: exclusively) old-fashioned connoisseurship as defined less by Berenson than by the Berenson myth: While Berenson is still widely held as having put connoisseurship ›on a firm footing‹, it has been widely forgotten that almost every scientific ambition has vanished from this notion, this ›art‹ of connoisseurship, especially as to the using of an elaborated terminology, a language that would allow experts to communicate and to make this (scientific) undertaking a collective enterprise. And this Alexander Perrig has attempted to bring back, on the field of Old Master drawings, and into that field. Largely ignored (with few exceptions) as to public reception, but this might be the second reason to think more about his mission, and about his ›Rosetta mission‹, his attempted landing on the comet of drawings that go under the name of Michelangelo, and his drilling into that comet very in particular. Thus: another documentation provided by the Museum of Art Expertise in cooperation with the Microstory of Art Online Journal takes shape here. We do not take side, except for methodological issues and thus for a vital and transparent debate on fundamental issues, without hubris and without premature identification with one or with the other side.

(Pictures: youtube.com/swissinfo.ch; see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j92Tsi0bVDY)  |

To set the scene two links: the first (short) review of Perrig’s Opus magnum of 2014: http://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/buecher/wundersame-vermehrung-1.18423586 To set the scene two links: the first (short) review of Perrig’s Opus magnum of 2014: http://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/buecher/wundersame-vermehrung-1.18423586and the probably best introduction to his thinking: a 2012 interview (in German): https://eikones.ch/fileadmin/documents/ext/publication/1099/1099_large.pdf |

ONE) Perrig’s Notion of Connoisseurship ONE) Perrig’s Notion of Connoisseurship»Those individuals with a musée imaginaire in their memory, mounted with an undefinable number of diverse impressions left by drawings, a memory that allows them as the case may be to classify a yet unclassified drawing off the cuff, are referred to as ›Zeichnungskenner‹ (›connoisseurs of drawings‹). The classification – example: ›this drawing is by young Perugino‹ – is per se worthless. If and to what extent it becomes relevant depends on how the connoisseur does support it with reasons. The connoisseur might find enough of justification in other connoisseurs, with other musées imaginaires in their head, supporting him from their heart or due to awe, or in ›running‹ of the drawing henceforth under ›Perugino‹. Considered scientifically this is practice of speech balloons.« »Als ›Zeichnungskenner‹ werden diejenigen Individuen bezeichnet, die ein mit einer unbestimmbaren Zahl verschiedenartiger Zeichnungseindrücke bestücktes musée imaginaire im Gedächtnis haben, das ihnen ggf. erlaubt, eine noch unklassifizierte Zeichnung aus dem Stand heraus zu klassifizieren. Die Klassifikation – Beispiel: ›diese Zeichnung stammt vom jungen Perugino‹ – ist an sich wertlos. Ob und inwieweit sie wissenschaftliche Relevanz bekommt, hängt davon ab, wie der Kenner sie begründet. Dem Kenner mag Begründung genug darin bestehen, dass ihm andere Kenner mit anderen musées imaginaires im Kopf von Herzen oder aus Ehrfurcht zustimmen und dass die Zeichnung fortan unter ›Perugino‹ läuft. Wissenschaftlich betrachtet ist das Sprechblasenpraxis.« (source: 2012 interview; above my translation from the German)  My commentary (DS): Personally I do like Perrig’s ruggedness, but I do not agree with everything he says here: this notion of connoisseurship is indeed a mainstream notion – attributions/classifications based on split-second intuitions, by intuitively having the brain scan a work of art for formal analogies and for clusters of formal analogies, or for impressions or clusters of impressions of whatever kind –, but for one: the hypotheses won by this practice are not worthless, but hypotheses to work with; suggestions, proposals, if one likes so, and it is up to the connoisseur or to the scientific community to test and to harden these hypotheses. This is the crucial point and as to this point I am not only agreeing with Perrig, but praising him for making this (once again) clear. Because for two: the critique of the split-second intuition approach (without explications following) is very old. Waagen, i.e. early 19th century connoisseurship, can be quoted with similar statements, Rumohr anyway; Morelli anyway… And this is one further point: Perrig (in his path-breaking Versuch of 1976) seems to remember only the intuitively working Morelli (that existed as well) and not the Morelli that demanded exactly what Perrig is demanding here: the giving of one’s reasons upon which the classificatory decisions (or the suggestion) are based. It seems to me that not only the tradition of scientific connoisseurship (that does lead to Perrig) has always been a very thin one, but the critique of the intuitive approach to connoisseurship makes clear that not even those who seek anew to establish scientific standards do seem to know this tradition really well. And for Giovanni Morelli intuitive thinking was welcome as a tool, for exactly the reason it is welcome for every connoisseur: for intuition does make suggestions, does propose a name or at least a direction of thinking. And any method of connoisseurship is meant to test that proposal subsequently. The one proposal that does stand the best methods of critique is (not necessarily truth, but) the most solid knowledge that we dispose of, in other words: scientific knowledge, by definition awaiting further testing by better methods that future doubtless will come up with. My commentary (DS): Personally I do like Perrig’s ruggedness, but I do not agree with everything he says here: this notion of connoisseurship is indeed a mainstream notion – attributions/classifications based on split-second intuitions, by intuitively having the brain scan a work of art for formal analogies and for clusters of formal analogies, or for impressions or clusters of impressions of whatever kind –, but for one: the hypotheses won by this practice are not worthless, but hypotheses to work with; suggestions, proposals, if one likes so, and it is up to the connoisseur or to the scientific community to test and to harden these hypotheses. This is the crucial point and as to this point I am not only agreeing with Perrig, but praising him for making this (once again) clear. Because for two: the critique of the split-second intuition approach (without explications following) is very old. Waagen, i.e. early 19th century connoisseurship, can be quoted with similar statements, Rumohr anyway; Morelli anyway… And this is one further point: Perrig (in his path-breaking Versuch of 1976) seems to remember only the intuitively working Morelli (that existed as well) and not the Morelli that demanded exactly what Perrig is demanding here: the giving of one’s reasons upon which the classificatory decisions (or the suggestion) are based. It seems to me that not only the tradition of scientific connoisseurship (that does lead to Perrig) has always been a very thin one, but the critique of the intuitive approach to connoisseurship makes clear that not even those who seek anew to establish scientific standards do seem to know this tradition really well. And for Giovanni Morelli intuitive thinking was welcome as a tool, for exactly the reason it is welcome for every connoisseur: for intuition does make suggestions, does propose a name or at least a direction of thinking. And any method of connoisseurship is meant to test that proposal subsequently. The one proposal that does stand the best methods of critique is (not necessarily truth, but) the most solid knowledge that we dispose of, in other words: scientific knowledge, by definition awaiting further testing by better methods that future doubtless will come up with. |

Two) Brief Chronology of a Historic Struggle Two) Brief Chronology of a Historic Struggle1930: Alexander Perrig born in Lucerne 1958: PhD (University of Basel) 1969: Frederick Hartt, The drawings of Michelangelo, New York 1972ff.: Perrig professor at Hamburg (1980ff. at Marburg; 1985ff. at Trier; Professor emeritus) 1975-1980: Charles de Tolnay, Corpus dei disegni di Michelangelo, 4 volumes, Novara 1976: Alexander Perrig, Michelangelo Studien I. Michelangelo und die Zeichnungswissenschaft – Ein methodologischer Versuch –, Frankfurt a.M/Bern [»Mein 1976 publizierter Versuch wurde […] vom Gros dieser Spezialisten [für ›zeichnerische Altmeisterprodukte‹] fünfzehn Jahre lang ignoriert und dann, als er in abgekürzter Form auf Englisch erschien, als Provokation und überflüssiges Gerede eines arroganten Besserwisserleins empfunden. Aus diesem Grund habe ich […] heute [2012] den Eindruck, dass die meisten Altmeisterzeichnungsspezialisten gar nicht gewillt sind, ihr Métier zu einer transparenten Zeichnungswissenschaft zu entwickeln.« (source: 2012 interview; some specific reasons why Perrig felt slighted are given below)] 1977: Perrig contributes to the multi-disciplinary Amsterdam symposium Authentication in the visual arts with his paper Authenticity Problems with Michelangelo. The Drawings on the Louvre Sheet No. 685 (proceedings were published in 1979) 1988: Michael Hirst, Michelangelo and his drawings, New Haven 1991: Alexander Perrig, Michelangelo’s drawings: the science of attribution, New Haven [abridged English version of the Versuch; reviewed for example, not entirely unfavourably, by William E. Wallace in Renaissance Quarterly 45 (1992), No. 4, pp. 857-859] 2006: London (British Museum) exhibition of Michelangelo drawings (Michelangelo Drawings: Closer to the Master; see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WRxJLB-pEk) 2007: Frank Zöllner, Christof Thoenes, Thomas Pöpper, Michelangelo, 1475-1564 - das vollständige Werk, Köln [In a review the German art historian Horst Bredekamp writes in the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit: »In den Zuschreibungsmethoden der neueren Kunstgeschichte lassen sich, grob gesprochen, zwei Auffassungen ausmachen. Eine vornehmlich angelsächsische Schule, der eine Mischung aus Präzision und Sentiment durch die Präraffaeliten des 19. Jahrhunderts in die Seele gepflanzt wurde, tendiert dazu, das zeichnerische Werk Michelangelos kontinuierlich auszuweiten. Eine deutsch-schweizerische, auf Stilanalyse setzende Schule hat das Œuvre im Gegenzug immer wieder reduziert. Der seit Generationen schwelende Konflikt lässt Golo Maurer, Spezialist der Architekturzeichnungen Michelangelos, von einer »Sittengeschichte der Attribution« sprechen. Die zweite Position, die in Luitpold Dusslers Zeichnungen Michelangelos (1959) markant bestimmt wurde, ist zuletzt durch Andreas Schumachers Michelangelos Teste Divine bekräftigt worden (2007). Ihre Ausformulierung hat der Schweizer Kunsthistoriker Alexander Perrig, Emeritus der Universität Trier und langjähriger Professor der Universität Hamburg, seit seiner Publikation Michelangelo und die Zeichnungswissenschaft (1976) wie kein Zweiter betrieben. Sein einsamer Kampf gegen die sich ausweitenden Zuschreibungen mündete in sein Buch Michelangelo’s Drawings. The Science of Attribution (1991), das eine der besten jemals formulierten Bestimmungen der Zeichnungskunst und der Möglichkeiten ihrer Analyse darstellt. Es ist zumeist auf Ablehnung gestossen, weil die Frage der Zuschreibung bis heute, einer Religion gleich, an die mentale Existenz der Zuschreiber und Besitzer vorgeblicher Michelangelo-Zeichnungen geht. Einen seiner Beiträge, in dem er eine Reihe von Zeichnungen dem Künstler Antonio Mini zuschrieb, hat Perrig mit Mini-Probleme überschrieben. Diese Ironie war eine Reaktion auf die Erfahrung, wie seine Forschung behindert, verdrängt, verschwiegen wurde. Seine historischen und stilkritischen Untersuchungen, durch die er das zeichnerische Œuvre Michelangelos radikal einschränkte, um die fraglichen Blätter anderen zeitgenössischen Künstlern zuzuschreiben, haben ihm eine ihresgleichen suchende Missachtung eingetragen.«] 2009: Frankfurt a.M. exhibition of Michelangelo drawings (»Zeichnungen und Zuschreibungen«; see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D5TRfKU-POQ; for a critical review of the catalogue see here: http://www.sehepunkte.de/2009/05/15965.html; also for a reply and a reply to the reply); an article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung by journalist Kia Vahland, who had been visiting the exhibition with Perrig, arouses other scholars to defend, respectively to justify the exhibition and its attributional policy [»Die vorgeschlagenen Zuschreibungen folgen dem aktuellen internationalen Forschungsstand und sind im Katalog ausführlich begründet, und zwar immer auch unter Einbezug der Position Perrigs. Leider ist er der sowohl mündlichen als auch schriftlichen Einladung zu einer gemeinsamen Diskussion vor den Originalen nicht gefolgt. Er verweigerte sie zu meinem Bedauern auch in heftigem Ton, als ich ihn zufällig in der Ausstellung traf, während er der Journalistin der Süddeutschen Zeichnung seinen Standpunkt erläuterte.« (Martin Sonnabend in the Frankfurter Rundschau) This again has to be seen against: »Perrig weiss z.B. zu berichten (schriftlich, 27.9.09), dass sich im März 1975 die Sunday Times anlässlich der Michelangelo-Jubiläumsausstellung im British Museum bemüht hatte, die Ausstellungskuratoren und andere britische Michelangelo-Zeichnungsspezialisten zu einem Gespräch mit ihm einzuladen und dass sie lauter Absagen erhielt, deren Begründungen in Form von Verbalinjurien gegen Perrig man in einem ganzseitigen Artikel der Sunday Times vom 13. April 1975 unter dem Titel »Michelangelo: How many of the drawings are really his?« nachlesen könne. Zwischen 1964 und 2008 sei er zu keinem einzigen der zahlreichen Michelangelo-Symposien eingeladen worden. 2008 seien dann zwei Einladungen wohl aus Rücksicht auf Berührungsängste anderer wieder annulliert worden.« (Christine Demele on sehepunkte.de, in a footnote to her reply to the reply)] 2010/11: Vienna exhibition of Michelangelo drawings (»Zeichnungen eines Genies«; see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nzr0Euqjnm8) 2011: an (according to Perrig) questionable Michelangelo drawing at auction at Christie’s (as already in 1993, 2000 and 2006; see: http://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/angeblicher-michelangelo-bei-christies-grosser-nacken-kleiner-po-1.1109040 and http://www.art-magazin.de/div/heftarchiv/2000/6/8149419407422161573/Wahres-Genie-oder-blasse-Kopie%3F) 2014: Alexander Perrig, Das Vermächtnis des Miniators Don Giulio Clovio (1498–1578) und die wundersame Vermehrung der Zeichnungen Michelangelo Buonarrotis, München  (Picture: amazon.de) |

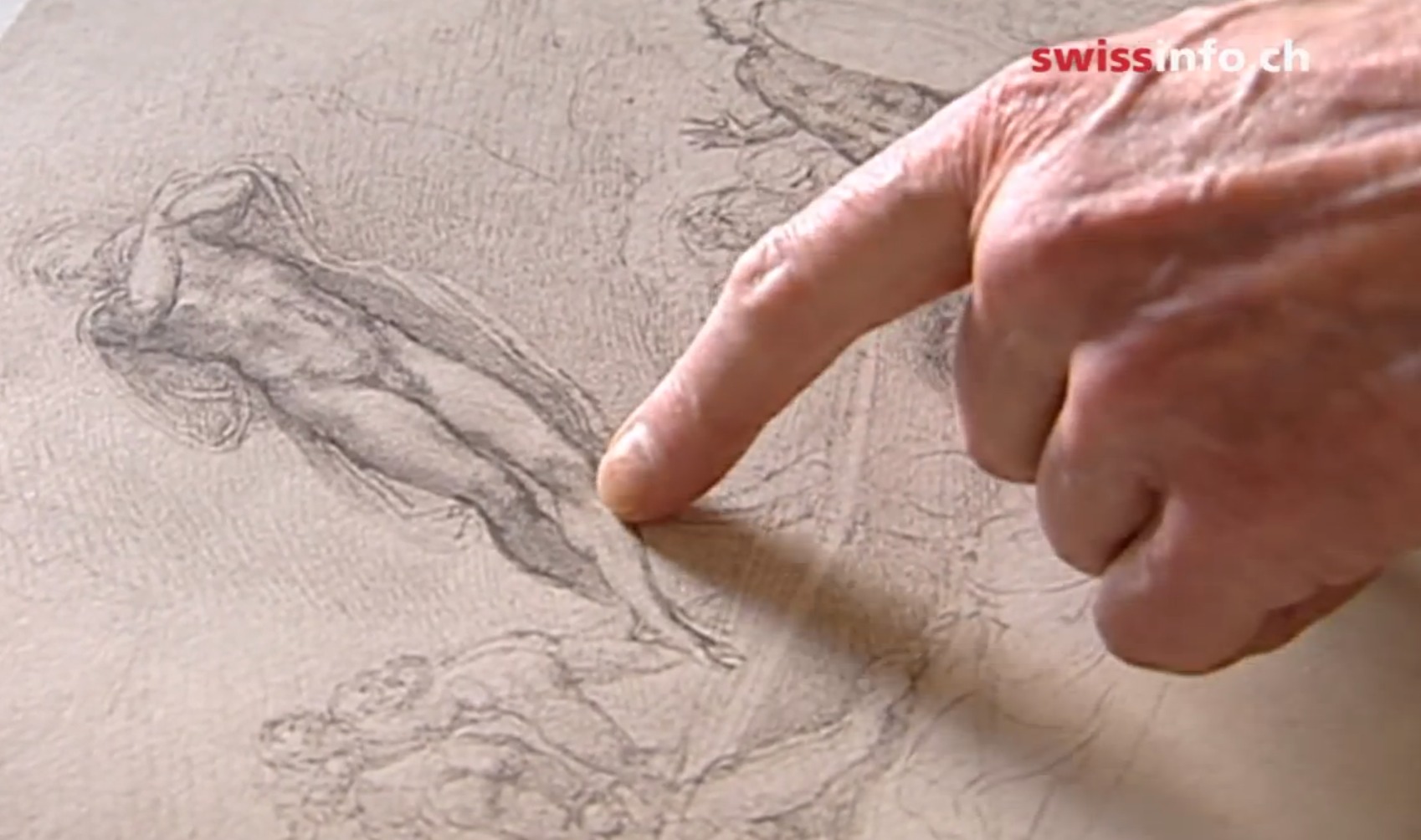

Three) Reading and Re-Reading Perrig: a (tentative) Résumé Three) Reading and Re-Reading Perrig: a (tentative) Résumé»Numbers themselves tell a fascinating story of a wildly fluctuating corpus. At the beginning of this century, Karl Frey’s catalogue of Michelangelo drawings included some 250 autograph sheets, while his contemporary Henry Thode accepted twice this number. Bernard Berenson considered 288 sheets genuine, while Luitpold Dussler included 350 sheets in his still standard catalogue. With Frederick Hartt, the number grew to more than 400, and with Charles de Tolnay, who had previously followed the conservative Frey, it expanded to more then [sic] 630. Now Perrig, brandishing the art historian’s equivalent of Occam’s razor, has slashed the corpus to fewer than 100 sheets.« (William E. Wallace, as cited above, p. 857f.) At the moment I am writing this tentative résumé I haven’t had a chance to look into Alexander Perrig’s new book. And this résumé is not meant to include a review, but to rise some questions that can be rised without actually having read the book (what we would like to provide here is an informed context to read that book). Will the book, for example, include an attempt not only to define, elaborate and to defend an already known position, but to actually answer to the various Perrig critics? And these critics were not, by the way, hostile critics without any exception. One might mention for example that Andreas Schumacher’s study, named above by Bredekamp, is not uncritical as to Perrig’s approach (and one might mention also – or not mention – that Bredekamp’s own expertise as to the connoisseurship of drawings is under scrutiny since an anonymous faker of Galilei drawings was capable to dupe him; and it does not help that Bredekamp admitted that this forger knew minor details as to the drawing style of Galilei that Bredekamp thought that he alone would know). One might mention, finally, that it is not clear at first sight for a neutral observer that one of Perrig’s main opponents is – or was, over the years – British art historian Michael Hirst (and William E. Wallace, for example, in his above brief review of numbers, does not name him). Much is a little bit more complicated here than it might appear at first, and, although frontlines seem to exist, these frontlines, under actual scrutiny, are often not as clearly drawn as one might think at first. Most important it seems to me to ask, if yet anyone has attempted to integrate various approaches that only seemingly do contradict each other, because, frankly, I am much reminded of pointless critique of Morellian connoisseurship that again and again (and simply wrongly) has claimed that someone wanted to replace any other’s approach with his own method. And it doesn’t seem to me that this was the core of Perrig’s struggle (but see my commentary to his notion of connoisseurship, above). At any rate it doesn’t seem impossible to me to think an intuitive approach as the first stage of an attributional process, followed by a testing of a hypothesis found by intuition (or by any other approach). And the tool of Strichbildanalyse offered by Perrig appears to me, like the Morellian method was meant to be (though often misunderstood), as one approach to test such a hypothesis, one approach among other approaches, and not at all excluding a testing for (or questioning of) ›quality‹ (or provenance, materiality, actual artistic content etc.). (The first stage, the intuitive judgment, by the way, might already include the testing for quality; and the improvised expertise by Perrig, given below, includes a testing for quality as well, here, anatomical accuracy) In spite of the metaphor of Occam’s razor the very method of Strichbildanalyse can be challenged, like any other method that works with formal analogies, on at least five levels: 1) On the level of reference material that the method has accepted to work with (it is Michelangelo’s handwriting that does play a crucial role here); 2) on the level of terminology that the method offers (is it differenciated enough to adequately name any sublety in drawing?); 3) on the level of theory as to the practive of drawing that is underlying the very terminology; 4) on a level of actual application of the method (the actual identifying of formal analogies); and 5) on a level of interpreting the findings (weighting the insights and including them within a balanced overall account or protocol). We would like to finish this brief résumé with a warm recommendation to read or re-read the Versuch of 1976. The book is not very voluminous, but very dense, and it offers insights to virtually any phenomena in drawing (the rugged style of Perrig might, more than that, inspire or even invite also to contradict him). As a further lure we would like to include and to give here Perrig’s opinion as to one particular drawing, not only as a lure to read or re-read his other writings (and to debate with him), but also, and not the least, to visit subsequently our Museum of Art Expertise that hereby is enriched with another expert’s opinion that, as usual, within the context of our museum, we would like to turn into and to perceive as an instrument of learning, of learning of how one might see (with someone else’s eyes), and here, of course, with the eyes of Swiss art historian Alexander Perrig.  Why not by Michelangelo? Alexander Perrig (as reported by the Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2011; source/picture: sueddeutsche.com; link above): »Der Künstler [Michelangelo] habe nach dem Leben gezeichnet und seine Modelle nicht wie dieser Zeichner um ihre Köpfe gebracht. Die Anatomie stimme nicht: Der Stiernacken sei im Vergleich zur merkwürdig eingeknickten Taille überproportional mächtig, der Kapuzinermuskel verlaufe inkorrekt über den gesamten Rücken, die Drehung der Schultern passe nicht zur Stellung der Hüften und die rechte Achselhöhle sei im Verhältnis zu dem viel zu schmalen Armansatz zu gross. Michelangelo aber kannte sich aus mit Muskelgruppen und Männerschultern, solche Missgeschicke wären ihm nicht passiert. Perrig schlägt vor, die Zeichnung dem Miniaturisten Giulio Clovio (1498 bis 1578) zuzuschreiben. Typisch für Clovio seien die starken, an manchen Stellen unsicheren und korrigierten Körperkonturen. Auch solch akzentuierte untere Wirbelsäulen finden sich häufig bei dem Zeichner. Das Gestauchte der Figur, ihre mangelnden Proportionen müssten Clovio nicht gekümmert haben, da er seine Zeichnungen später auf Miniaturen übertrug, sie also auf Handgrösse reduzierte. Clovio könnte Michelangelos Rückenansicht des gebadeten Hosenanziehers gekannt und als eine von mehreren Vorlagen benutzt haben.« |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM   (Pictures: cbc.ca; youtube.com/swissinfo.ch; bg picture: yalepress.yale.edu) |

The basic reading: Alexander Perrig, Michelangelo Studien I. Michelangelo und die Zeichnungswissenschaft – Ein methodologischer Versuch –, Frankfurt a.M./Bern 1976 The basic reading: Alexander Perrig, Michelangelo Studien I. Michelangelo und die Zeichnungswissenschaft – Ein methodologischer Versuch –, Frankfurt a.M./Bern 1976  |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Thank you for visiting the Online Journal (and think also of visiting the Virtual Museum of Art Expertise…) http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/TheVirtualMuseumOfArtExpertise |

And this looks like real Viennese, i.e. Albertinese courtesy to me… Thank you, Dr. Gnann

(picture: youtube.com/swissinfo.ch)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS