M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

An Expertise by Berenson

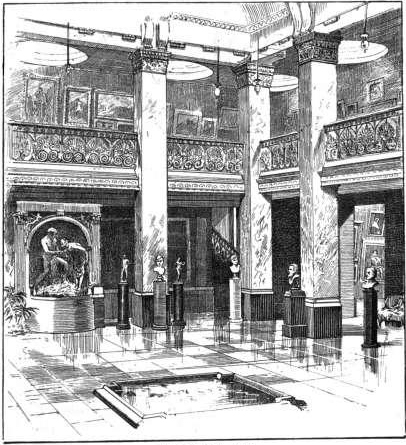

The Virtual Museum

of Art Expertise –

An Expertise by Berenson

Berenson in 1891 (picture: npg.org.uk)

»More Morellian« – An Expertise by Bernard Berenson

For once Mr. Bernhard Berenson was keen to be verifiable. Which means that, in this particular case, he laid open all his reasons, all his reasoning for vindicating a picture to a particular painter, in this particular case to Giorgione, and this in his 1895 ›counter catalogue‹ to an exhibition of Venetian Painting in the New Gallery.

But who would have dared to contradict him? Since this was about a picture in Her Majesty’s collection. (And still one ought also appreciate, while perhaps not all too much admire, all the relativistic mannerisms and magic tricks to be found in this opinion, and, last but not least, the Berensons’ – in some sense: openly declared – confirmation bias.)

Mary Costelloe (picture: npg.org.uk)

[p. 38] »Of the remaining works attributed to Giorgione, only one is a painting, the rest being drawings. But that one is, in my opinion, by Giorgione himself. It is the Head of a Shepherd (No. 112) from the Hampton Court Gallery. [original note: A mediocre but still adequate reproduction of it will be found in my Venetian Painters of the Renaissance] A recent writer on the pictures of this collection [Mary Costelloe, the later Mrs Berenson, who wrote under the pen name Mary Logan] has spoken of it in words that I cannot do better than quote: — »The face is so radiantly beautiful that even retouching and blackening have not been able to hide the fine oval, the exquisite proportions, the warm eyes, the sweet mouth, the soft waving hair, and the easy poise of the head.« [original note: Mary Logan, Guide to the Italian Pictures at Hampton Court, The Kyrle Society, 1894 (Price 2d.), p. 13] This is not too enthusiatic a description of the supreme beauty and poetic charm of this wonderful head. I can scarcely hope that many of those who see it in the wretched place given to it in the New Gallery will feel so ecstatic about it as I do; but then they have not had my good fortune of studying it under the full light of the sun [note the importance of particular lighting in all the testimonials of seeing that picture, see also our note below, with reference].

This picture, whose first discoverer was Morelli, is no longer accepted as a Giorgione by the Morellians [probably: Gustavo Frizzoni, Jean Paul Richter; note that, here, Berenson does not associate with them]. If their master, they say, had seen it in a good light, he never would have taken it for a Giorgione [in fact Morelli very likely did see it in a good light, but only declared himself not to have seen it properly, questioning the attribution to Giorgione himself in the revised edition of his studies on the Dresden gallery, a fact Berenson probably did not know]. It is easy to say such a thing now that Morelli is dead; but its being disputed compels me to defend it. Let us in the first place turn to a morphological comparison of this head with those few pictures by Giorgione that are least called in question.

Now attributed to Titian (picture: wikimedia.org)

Perhaps the most striking resemblance of all is that of this head to the head of the Sleeping Venus at Dresden, the same broad face, broad brow, the same modelling of the lids, the same shape of nose and mouth. With the Knight of Malta in the Uffizi it has in common the broad brow, and the precise way of opening the eyes, and of modelling the lids; with the Loschi Christ bearing the Cross (at Vicenza), it has in common the eyelids, the mouth, and the folds of the drapery; with the Castelfranco and Madrid Madonnas it has in common the mouth; with the Berlin portrait [the so-called ›Giustiniani portrait‹] there is also [p. 39] a great likeness in the folds (cf. particularly the R. sleeve), and in the mouth; and, finally, the Hampton Court Shepherd shares with all of Giorgione's universally-accepted works, the dome-shaped cranium.

The Ex-Lochis Christ. Now ›Circle of Giovanni Belini‹

(picture: gardnermuseum.org)

Detail from the Pala di Castelfranco

What, then, is the fatal flaw in this picture? Alas! it is the hand holding the flute, which, as it happens, is not at all unlike Giorgione's hand — he, by the way, has a number of characteristic hands — but which is, unfortunately, in the opinion of some critics, more like Palma’s hand, and, in the opinion of others, more like Pordenone’s. Therefore, despite the diametrical opposition in every other morphological detail, and, above all, in spirit, between this head and any and every authenticated work by either Palma or Pordenone, the fatal hand condemns it to be a work of one or the other of these inferior painters. This, truly, is being more Morellian by very much than Morelli himself!

Vienna

But let us enquire a little more closely into this question of the hand. In so far as Giorgione has at all a stereotyped hand, what is its most peculiar characteristic? It is the tendency to give great prominence and looseness to the forefinger, as we see in the Knight of Malta, and, to an exaggerated degree in the lulus of the Evander and Aeneas (alias the »Three Magi«) of Vienna. Now, what is the greatest peculiarity in the hand of the Shepherd ? Precisely this looseness and prominence of the forefinger. In so far as the hand is unsatisfactory in other respects, I think it is due to the condition of the picture. There is, at all events, nothing surprising in the fact that people who exploited Giorgione so much as did Palma and Pordenone, should have adopted some [o]bvious mannerism — always the easiest thing to imitate — of the supreme master [this is exactly the opposite of an orthodox Morellian view which assumes that imitators just neglect these mannerisms and have their own; but Morelli himself was not that orthodox in that respect and assumed at times that also such mannerisms could be copied].

Budapest

Cariani’s hands

Examples of Palma Vecchio

Cremona

But if we really must make the hand the palladium of identity, what shall we say of the now universally accepted Portrait of a Young Man at Buda-Pesth? That masterpiece has a hand quite unlike any other in Giorgione, but very close to Cariani’s most characteristic hand, and closer still to the hands in such a Pordenone as the altar-piece in the Cathedral of Cremona. Were one to go by the hand, the Buda-Pesth portrait would certainly be a Pordenone, particularly as in no other accepted work do we find Giorgione so grey in tone and so self-consciously melancholic as in this portrait, while this spirit is close to Pordenone, and this grey tone is singularly like the Cremona altar-piece. Nevertheless, I cannot let myself be run away with by these outer resemblances, nor [p. 40] even the resemblances of spirit, because I know Pordenone, and I know that great though he was, he was utterly inadequate to such an achievement as the Buda-Pesth portrait. Its likenesses to Pordenone I account for in this way. Of the

various sides of a supreme master, each follower finds one that appeals more strongly than any other to his own temperament. Pordenone, inclined to be haughty and over self-esteeming, found himself set in vibration by the Buda-Pesth Young Man, and naturally said to himself, »This is what I want to say about things, and this is therefore the way to say it.« And thereupon he began to exploit that one segment of Giorgione's art.

Now that I have done what I could to prove by internal evidence of a morphological nature that the Shepherd with a Pipe is by Giorgione; now that I have explained how it may happen that the hand should remind some people of Palma and some of Pordenone, let us see what outside evidence there may be for the authenticity of this picture.

(Picture: wikiart.com)

That subjects akin to this were treated by Giorgione, we know well from the Anonimo, who saw in the Palace of Zuane Ram »the head of a boy who holds in his hand an arrow,« and »the head of a shepherd who holds in his hand a flute.« [original note: Anonimo, ed. Frizzoni, p. 208] But we have something even more precise. The self-same head that occurs in the Hampton Court Shepherd, is found in a picture in the Imperial Gallery at Vienna (No. 243), which represents »the young David whose luxuriant hair falls down on both sides of his face. He wears a breastplate« — the catalogue continues — »and holds the sword of Goliath in his R. hand, while with his L. he places the giant’s head on the parapet behind which he is standing.« [original note: E. v. Engerth, Vol. I, p. 171] Now this picture is obviously a copy (let anyone who is tempted to think the Hampton Court Shepherd only a copy, compare it, by the way, with the Vienna picture!), but it is an old copy, for we find it mentioned in the collection of the Archduke Leopold William at Brussels. Yet, copy though it be, it is of interest to us, for if we have the imagination to supply this copy with a quality of execution adequate to the quality of conception, we arrive at nothing less than a masterpiece by Giorgione himself. And here Vasari comes to our aid. Among the pictures he saw in the house of the Patriarch of Aquileia, he mentions as being by Giorgione »a David with a shock of [p. 41] hair, such as used to be worn in those days, down to the shoulders, lively and coloured, so as to seem flesh and blood. He has an arm and the breast covered with armour, and holds the head of Goliath.« [original note: Vasari, ed. Sansoni, IV, p. 93] Allowing for the difference in exactness between the casual Vasari and the scrupulous accuracy of the modern cataloguer, Vasari’s and Von Engerth’s descriptions certainly apply to the same picture. The Vienna David is, therefore, indubitably a copy after a Giorgione. Now, as the head in the Vienna picture is identical with that of the Hampton Court Shepherd, it follows that the latter is also an original, or a copy after an original by Giorgione. As to which of the two it may be, that is no longer a matter of quantitative reasoning, and argument concerning it is, therefore, useless. All that can be done is to beg the competent in this matter, as I have already done, to compare the one with the other, and to note the gulf between the quality of the David and that of the Shepherd, giving them only this further hint, that Giorgione, while always supreme in his conceptions, did not live long enough to acquire a perfection of draughtsmanship and chiaroscuro equally supreme, and that, consequently, there is not a single universally-accepted work of his which is absolutely free from the reproaches of the academic pedant.

(Picture: britannica.com)

And here is Kenneth Clark’s description of Bernard Berenson’s working procedures from The Burlington Magazine No. 690 (September 1960), to be assessed not only for its content, but also for its suggestive style: I would call it a suggestive rendering of something meant to be suggestive:

»Mr Berenson's own procedure when considering a picture rather added to this feeling of magic. He used to tap the front of the picture with a delicate finger and then listen intently as if expecting an almost inaudible voice to speak to him. Then after a long pause he would pronounce a name. I hardly ever knew him explain or give his reasons - quite rightly, because they would have been full of complexities and imponderables. And of course he tapped the picture in order to find out if the panel was in good condition or if the canvas had been relined. All the same I can well understand why people without his visual memory and rapid processes of deduction thought there must be some trick. ›I soon discovered‹, he said, ›that I ranked with fortune tellers, chiromantists, astrologers - and not even with the self-deluded of these, but with the deliberate charlatans.‹«

In my eagerness to vindicate for Giorgione this wonderful head, I forgot to speak of a portrait bust attributed to this master, of exquisite quality, but deplorably bad preservation, which belongs to Mr. A. H. Savage Landor (No. 15). It may have been a work by the young Titian, or else only a copy after such a work, the copy by Polidoro Lanzani.

Of the seven drawings ascribed to Giorgione only one is really by him, the early sketch for the martyrdom of a saint, from the Chatsworth collection (No. 319), reproduced in

Morelli. [original note: Italian Masters: Munich and Dresden Galleries, English translation, p. 225 (N.B. – The drawings from Chatsworth, Nos. 838-883, are not referred to in this essay, having been added to the exhibition at a date subsequent to the writer’s visit to England] Of the remainder, Nos. 312, 334, 342, and 348 are nothing in particular; the red chalk sketch for a Death of Peter Martyr (No. 320, also from Chatsworth) is Pordenonesque, and a Saint Preaching (No. 321, from the same collection) is of the school of Gentile Bellini, possibly by

his follower, Benedetto Diana.

[p. 42] We have now ended our survey of the pre-Titianesque works exhibited in the New Gallery. A detailed examination of the sixteenth century Venetians would reveal an even greater number of questionable attributions, and would entail the resuscitation of many wholly or half-forgotten painters — the real authors of a large proportion of the pictures here which pass under the ringing names of Titian, Bonifazio, Palma, Paris Bordone, and Paolo Veronese. Such a study would require not a pamphlet but a book, and as it would chiefly concern artists whose names thus far have been but seldom heard, it could not hope to have the least interest for any but specialists.

BERNHARD BERENSON.

February 7th, 1895«

(Source: Bernhard Berenson, Venetian Painting, Chiefly Before Titian, at The Exhibition of Venetian Art, The New Gallery, 1895, London 1895, pp. 38ff. [some original notes slightly adjusted])

Compare also the first hand testimonials as to Morelli seeing the Hampton Court picture here. For a bunch of alternative attributions see here, and for Morelli searching for Giorgionesque and Titianesque characteristices here.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS