M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

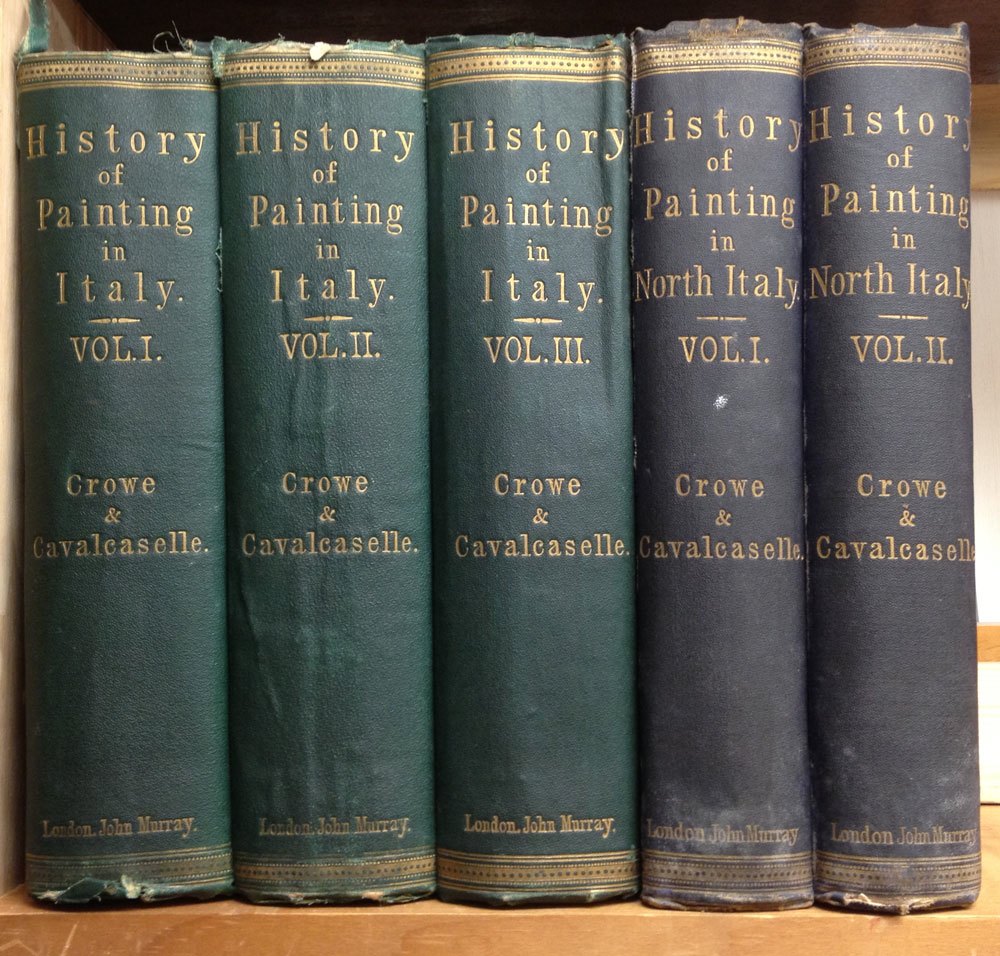

An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

The Virtual Museum

of Art Expertise –

An Expertise by

Crowe and Cavalcaselle

(Picture: doullbooks.com)

»…such a Last Supper as this, where Christ gives the meat to Judas, a common mortal, and outside the cooks clean the dishes near the kitchen fire,

the cat steals the scraps, and the servant points with his thumb in the direction of the supper as if commenting upon the conduct of the guests…«

A Cat Stealing the Scraps or: This Minuteness of Criticism

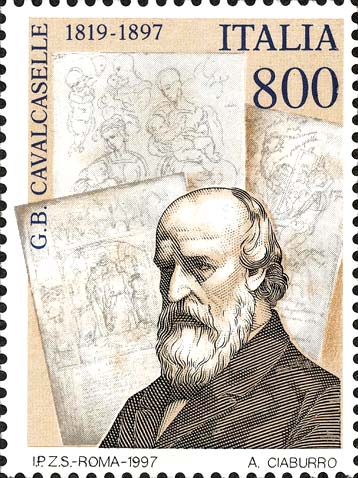

While writing their history of painting in Italy the two collaborators, Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, showed not all too anxious to delve into complicated matters of attribution (and this nonchalence, among other things, worked as a provocation for Giovanni Morelli, their counterpart). At some point, however, that is, in the fourth volume of their monumental work, when discussing Verrocchio, the authors suddenly feel like begging pardon for a sudden outburst of minute criticism (see short text below on the left).

And indeed, their history of painting in Italy is not a collection of expertises, but here and there, as a matter of fact, the two connoisseurs did talk attribution, did name identifiers and thus did join the everlasting debate.

We feel inclined to include two excerpts from that classic history of painting into our book of expertises. And for once it is not about Italian Renaissance painting, but about 14th century art, namely about a cat stealing the scraps (in truth a dog!). In a representation of the Last Supper. In the Lower Basilica of Assisi. And about a sculpture. By Verrocchio.

(Picture: artearti.net)

Joseph Archer Crowe

(1825-1896)

[p. 98] »Ghiberti, who strangely omits to mention Pietro Lorenzetti, dwells with unaccustomed rapture on the beauty of a series painted by Ambrogio in San Francesco of Siena. It is not long since a part of these paintings was rescued from whitewash and placed in two chapels of the convent church. Amongst them is a Crucifixion unnoticed by Ghiberti or Vasari and composed of figures larger than life. The Saviour, a powerful and robust nude, not unnoble in its muscular development, but with a low forehead and eyes like those of Pietro Lorenzetti, hangs on the cross, bewailed by a flight of the usual vehement angels. At the [p. 99] foot of the instrument of torture, St. John grieving and the Virgin motionless in the arms of the Marys, forms the usual accompaniment to the principal figure. St. John, of muscular frame and great size, expresses the most realistic and grimacing grief, with contracted brow, open-mouthed, and disfigured by a pointed chin and massive hair, cut straight across a high forehead. Yet there is such tremendous energy in the head that its vulgarity disappears. The power of Niccola Pisano and the exaggeration of Michael Angelo seem combined in the group of the Marys; and the Virgin, with wrinkled brow and eyes contracted into angles by spasms, has cast her arms wildly over the shoulders of her attendants. Her high forehead, close eyes, and mouth with the upper lip drooping over the lover at the corners, are essentially characteristic of Pietro Lorenzetti, and convey the impression that he studied most masculine female models. Yet the genius of the painter enables him to give interest to a form otherwise disagreeable, by the extraordinary force which he displays. The energy and power which mark this fresco are found equally strong in a figure in the refectory of San Francesco representing the Saviour rising from the tomb. His form is grave and majestic, though the features have no beauty; and the expression is so fine, the drawing so bold in its angular force, the somewhat broken movement of the joints so vehement, that one forgets the defects in the vigour which the master displays.

The variety which distinguishes the Sienese from the Florentine school is now sufficiently clear. It may be noted in a series of frescoes in the north transept of the Lower Church of San Francesco at Assisi assigned by Vasari to Pietro Cavallini.

The Sienese school was characterised from the first by a peculiar mode of distributing the subjects of the Passion. Duccio and [p. 100] Barna preserved it alike, commencing with the Entrance into Jerusalem, to which they gave a double space, and closing with the Crucifixion, to which a fourfold area was devoted. The last scene of the mournful drama thus received additional importance, and was intended in every sense to possess overwhelming interest. The Florentine, it is hardly necessary to say, devoted to each incident an equal space, and their simplicity in this respect may be studied not only in Florence and Padua but in Assisi, by the side of these Sienese frescoes which have so long been assigned to a Roman painter. They are indeed distributed not only as Duccio and others were wont to do, but as was usual with the painters of crucifixes in the eleventh and twelfth century, who made the Redeemer colossal and the scenes of the Passion subordinate. They occupy the sides, the vaulting, and the end of the transept. Beginning on the eastern curve with the Entrance into Jerusalem and the Last Supper, beneath which are the Saviour washing the apostles’ feet, the Capture, the Self-murder of Iscariot, and St. Francis receiving the Stigmata; and continuing on the western with the Flagellation, the Road to Calvary, and the Crucifixion, which with its fourfould size and colossal figure of the Saviour is thus made to face the Miracle of St. Francis and the Stigmata. In two courses on the northern end of the transept and about the arch leading out of it are painted the Deposition, the Entombment, the Resurrection, and the Limbus.

The pictures are parted in the usual manner by ribs of ornament, at the corners of which lozenges contain figures of prophets or apostles, and smaller medallions enclose angels. The character, the type of these apostles and angels, so clearly derived from the examples of Duccio and his predecessors, would alone prove the frescoes to be by a painters of Siena; but looking at the entire series, the impression which it creates is that of a work conceived and carried out by one hand, in general features like the Cappella San Martino of Simone, because it is by an artist of the same school, though stamped with the individuality of another and perhaps greater genius, unlike those of the southern transept or the Orsini chapel, because they are by painters who laboured on different principles and in another spirit. Setting aside, however, all other considerations for the sake of going into [p. 101] the analysis and study of the matter, the frescoes of the north transept are Sienese in distribution and composition, and are the development of the manner of Duccio, Ugolino, and Segna. The types are theirs, the old ones modified by the spirit of a superior genius. The figures, vehement in action, often vulgar in shape and face, frequently conventional, and in some cases downright ugly, are rescued by the extraordinary power with which the movement and expression are rendered. The broad and sweeping draperies are more closely fitting than the Florentine and cut on different models. All this sufficiently characterises a painter whose style can be distinguished even from that of his brother, and that is Pietro Lorenzetti. Passing from the general to the particular and taking the subjects in their historical order, we cannot fail to remark that the Entrance into Jerusalem is conceived and executed as Duccio conceived and executed it, with the same figures, crowd, and edifices, but bolder and more vehement in action, as if the soul of Duccio had entered the frame of Lorenzetti. None but Pietro ever painted such a Last Supper as this, where Christ gives the meat to Judas, a common mortal, and outside the cooks clean the dishes near the kitchen fire, the cat steals the scraps, and the servant points with his thumb in the direction of the supper as if commenting upon the conduct of the guests, whilst the moon and stars symbolically suggest an evening meal. Who but Pietro could impart to vulgar types and attitudes such power and animation as are to be found in the apostles in a room stripping their feet, whilst S. Peter reluctantly permits the Saviour to kneel and wash him? In the Capture we see the illustration of a well-known custom which assigns to the Saviour a superior stature and grave features, mindless in their serenity of the cares of this little world; whilst in the face of Judas, the expressive ugliness which Leonardo da Vinci sought with so much labour proves Pietro’s talent and study of the human features.

(Picture: Ricardo André Frantz)

»This Minuteness of Criticism«

(Verrocchio, Christ and St. Thomas)

»[p. 239]

The Incredulity of St. Thomas at Orsanmichele gives occasion

for a fuller development of flesh parts. St. Thomas, in motion

and probing the wound, is youthful and plump, but the fulness

exaggerated by Lorenzo di Credi is already marked. The figure

is surprising for the advance in art which it proclaims and the

motion which it renders. The Redeemer raises his right arm

and uncovers his side. The figure has some of the rigidity

of bronze. The type is somewhat aged and pinched in the

features, the flesh sparingly covering the skeleton of bone in

the frame; but this is a peculiarity of Verrocchio in painting

in bronze, apparent in the Baptism of the Academy of Arts at

Florence and in Leonardo. Some coarseness and puffiness in the

extremities are also to be noticed, but the group in its totality is

a fine and beautifully polished bronze. The most remarkable

point in the work is the involved nature of the drapery. It is no

longer broken like that of the Pollaiuoli, but betrays the effort to

obtain round and sweeping lines, combined with a method of [p. 240]

closing the puff of the cloth above the eye of the fold. Searching

detail sacrifices the planes of the flesh. The stuffs have the

appearance of being lined, or double like those of Lorenzo di

Credi; and the drapery gains a material form similar to that

which characterises the Umbrians, Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, Perugino,

and even Pinturicchio. The reader must pardon this minuteness

of criticism. It helps us to test the value of Vasari’s assertion that

Verrocchio was one of the masters of Pietro Perugino, and enables

us to admit that he may in this point be correct. Had we not

material proof that Lorenzo di Credi was Verrocchio’s pupil, we

should guess the fact from the analysis of the bronze of Orsan-

michele; and it is possible that Lorenzo, who was twenty-four

years of age when the work was completed, may have been

assistant to the master at that time.«

(Source: J. A. Crowe / G. B. Cavalcaselle,

A History of Painting in Italy, vol. 4

(Florentine Masters of the Fifteenth Century ), London 1911

(ed. Langton Douglas, assisted by G. De Nicola), pp. 239f.;

notes omitted)

In the Flagellation the Saviour appears, as in all Sienese pictures, with His back ot the spectator and receives the stripes from two soldiers. A natural, well studied nude, muscular and energetic in movement, but unnoble in form, reveals as ever the [p. 102] tendency of Pietro Lorenzetti. We note too in the Procession to Calvary the two thieves in long convulsive stride, a soldier galloping on horseback, a guard rudely keeping back the Marys, the Saviour carrying His Cross, the Virgin masculine in the energy of her step, in features resembling those of the fresco in San Francesco at Pisa, St. John Evangelist quite to the left, and the horsemen closing a long array, the whole in a distance with crenelated houses cut square at the embrasures after the Sienese fashion.

The Crucifixion is mutilated by a large stone altar which breaks off the figure of the Saviour at the knees, and agreeably to Sienese custom, He contrasts by His size with the neighbouring thieves. His form is simpler yet still identical with that of Duccio – thin, long, hanging forward, lifeless, low in forehead, with bony brow, nose depressed and mouth drooping at the corners. Terrible grimace, herculean frames, and vulgar grief mark the circling angels about the cross, which contrast, as all Sienese

angels do, with those of Giotto and prove once more how different the ideal of the two schools was. As regards type and symmetry and balance of composition, Lorenzetti shows his inferiority to the Florentines. The good thief with his arms over the cross, as ever, a muscular nude, proves Pietro’s rare talent and study of nature and his successful rivalry with and superiority over the Giottesques. The impenitent, vulgar in face, in agonising pain as the executioner breaks his bones, realises the idea of strong suffering and writhes in every fibre.«

(Source: J. A. Crowe / G. B. Cavalcaselle, A History of Painting in Italy, vol. 3 (The Sienese, Umbrian, & North Italian Schools), London 1906 (ed. Langton Douglas), pp. 98-102; notes omitted here)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS