M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY Cabinet I: Introduction  |

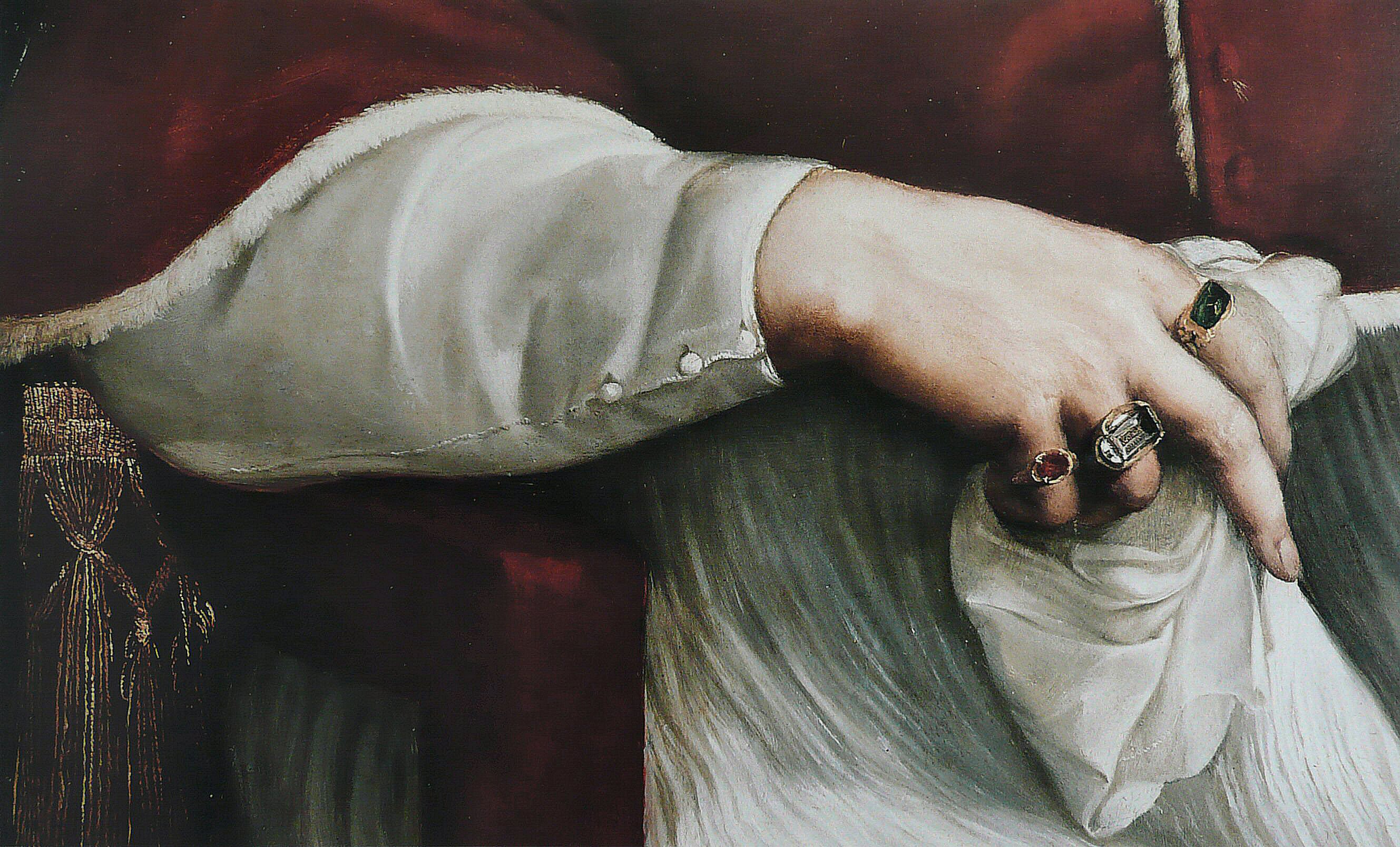

It does not make things easier, curator Stephan Kemperdick said in 2006, that Hans Holbein the Younger, as his father – and as his Basel master Hans Herbst – signed with his initials HH (Kemperdick 2006, p. 12). But on the other hand, Hans Holbein, if it is also true what Kemperdick says as to the artist’s rendering of hands and noses, seems to be an ideal test case to apply the Morellian tests and controls. If, one might add, if the Morellian culture of applied style criticism would be still alive and well, Holbein might be our possible test case.

›Who does juxtapose the portraits must assume that the depicted persons are all related to each other: the nose, for example, is almost in every case identical, und the 70-year-old Archbishop of Canterbury does show the same hands as the young lady with a squirrel.‹

»Wer die Porträts nebeneinander legt, muss vermuten, die Abgebildeten seien alle miteinander verwandt: Die Nase etwa ist fast immer identisch, und der 70-jährige Erzbischof von Canterbury hat die gleichen Hände wie die junge Dame mit dem Eichhörnchen.«

Stephan Kemperdick (Kemperdick 2006, p. 12)

But is, we must ask, and yet in and with this introduction, is Morellian connoisseurship alive and well at all (and has it ever been, since it was meant as a project, to be developed in and into the future)?

Or has it rather sunken into half-oblivion (never having been developed further, as Morelli actually had wanted it to be developed)? While Morelli, nonetheless and without any doubt, has become a symbolic figure. Symbolizing a decidedly rational approach to attributional studies.

But this on the other hand, might be an all too narrow view of Morelli. And with this introduction to our studiolo, we should like to take a broader view, in introducing to our discussion of the connoisseurial practices of Giovanni Morelli, and with giving a sketchy portrait of his intellectual approach. And with suggesting a renewed vision in the end, a compass, designed to recall and to clarify what scientific connoisseurship, at the day of Morelli, was all about and thought to be. And what it might be in the future. To every connoisseur to find out if he or she could be regarded as working in the Morellian tradition or not.

CABINET I: INTRODUCTION

(ONE) THE CASE OF HOLBEIN

AND THE MORELLIAN SITUATION

(TWO) FROM THE MUSEUM OF METHODS?

(THREE) A MORELLIAN VISION![]()

ONE) THE CASE OF HOLBEIN AND THE MORELLIAN SITUATION

When in 1878 Giovanni Morelli imparted some essential knowledge to a man named Jean Paul Richter, who was to become his most dedicated pupil in the years to come, some basic knowledge about how to approach attributional studies, Morelli made it clear that method, as Giovanni Morelli understood method, referred in a very general sense to a rigid study of form (see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 March 1878 (M/R, p. 34f.)).

Given this very general notion of method, Morelli went on to distinguish a more basic study of form, resulting with a connoisseur, after being dedicated with this kind of studies for quite some time, being able to distinguish various schools in painting; and he went on to address the particular problem that we should like to call the quintessential Morellian situation here, something that the connoisseur was only to face on a more advanced stage, namely the problem to distinguish closely related individual styles, the problem to tell master from pupil, master from copyist, in brief: to tell differences where differences hardly could be spotted, since one was facing, in particular situations, manifestations of stylistic almost-similarity.

And in spite of its having become notoriously famous as a brand, as something also with a kind of life of its own, the having become notoriously famous Morellian method had actually been developed not to address any problem of attribution or any imaginable problem, but exactly this: it had been designated to address exactly this very specific problem that we may also call the problem caused by clusters of high-degree similarity.

Distinguishing the almost or seemingly indistinguishable – this had also been the problem that Giovanni Morelli, several years earlier, had been struggling with. This exact problem had caused him to think about how to attain a higher degree of certainty, if one was wanting to know exactly with what one was dealing with.

And the case of Holbein might serve us well to illustrate this very specific problem in a more general level.

A preparatory drawing to the portrait of William Warham, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for example, does exist (compare on the issue for example Bätschmann/Griener 1997, p. 164), a preparatory study, however, that does not show us the Archbishop’s hands. And if now, as is indeed the case, two versions, two high quality realizations of the Archbishop’s portrait do exist (or even more than two), versions that present us with the question of how these versions are possibly related to each other – then we do face exactly what we have called the quintessential Morellian situation. It is about spotting nuances, characteristic traits that might us help to answer the question, if possibly one of these two versions had been realized by Holbein himself, and possibly the other by one of his apprentices. And here also the missing hands come in again, the hands not being represented in the preparatory drawing, so that one might also assume that, if a pupil did realize a version afther the preparatory drawing, his routines as to the representing of hands might possibly give us, given that we know them, a clue as to possible authorship. And if it is indeed true that already authenticated paintings by Holbein do show, as Stephan Kemperdick does say, regularities as to the rendering of hands, we might take our chance here in taking a look at how exactly Holbein did represent hands, compared to how his pupils, as far we know them, routinely did represent hands (in case, for example, on a preparatory study hands were lacking, but still, as we only do imagine here, had to be realized in paint). And in regarding our respective observations as clues, we would be allowed to call ourselves Morellian apprentices – because this would be exactly following the recommendations of Giovanni Morelli, and applying his recommendations to a non-Italian painter, but to a painter who apparently would give us a chance to actually apply the Morellian method, if it is true that his rendering of hands shows distinctive characteristics, and we might possibly result with telling, as Morelli said in 1878, ›master from pupil or copyist‹, if not in any case and necessarily (for example if a particularly copyist did also study the rendering of hands by Holbein; and for such reasons Giovanni Morelli did also prefer to give such formal clues only a relative weight – in context).

Last but not least we have to stay aware that these working with clues does not at all mean to dismiss a sense of quality that we might also dispose of, and the working with clues, according to Morelli, was meant to control what our sense of quality, our intuition might say or suggest us as to the authorship of two (or more) seemingly closely interrelated paintings in question.

The case of Holbein might serve us well as to a setting the scene. But we might now also be wanting to look at some more recent debate as for example the debate about the portrait of Pope Julius II by Raphael (or better: about various versions of such a portrait in regard to the question of authorship), a test case that exactly presents us not with any problem, but with a similar problem, and again with the quintessential Morellian situation. And here we might be curious to know, wanting to know if Morellian practice is actually alive and well, and more specifially: if and to what extent the Morellian approach is still being in actual use.

(Picture: staedelmuseum.de)

It is not at all far-fetched to think of art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli, if he had lived today, as a blogger. An art historical online scene, is not only existing but thriving, and Morelli, who showed little patience and was easily bored if he had to carry out a larger work systematically – he was actually lacking scientific discipline – could easily be imagined to be a blogger in his not representing an academic establishment, and every now and then shocking the (German) academia with sneering comments. And every now and then also complaining that he was not enough taken seriously, and every now and then writing little satirical pieces, to entertain himself, and to deposit somewhere, his thoughts as to a future establishing of scientific connoisseurship.

On the other hand one might also think that a weblog certainly can be an appropriate tool to now and then comment upon certain attributional matters, but it might not necessarily be the ideal platform to unfold, in a larger sense, what Giovanni Morelli had imagined scientific connoisseurship to be. Since it is, it would be about stylistic regularities (and decidedly not about single and possibly accidental likenesses, that easily could be illustrated by showing a minor number of pictures), but about documenting, for example, larger serial developments, or having to put online larger series of reference pictures, especially if it is about the distinguishing of a major painter like Raphael from his various and numerous pupils (many connoisseurial debates seem to be focussed on the central painter alone, because wishful thinking seems to want only a certain hypothesis, an not alternative hypotheses seriously to be tested, resulting in almost classical systematic distortion). And to establish such comparison seriously and reasonably, one had to think about documenting not only characteristic traits of one singular painter, but to have ready and to know about characteristic traits of all the more secondary painters surrounding Raphael, groups of painters that also might be called his satellites. But who, even if being satellites, might dispose of, even if lacking a characteristic style of their own, at least of what Morelli use to call ›habits of the hand‹, features that he considered not to be expressions of a painter’s individual mind, but rather being the result of mechanical routines, yet not lacking individuality, if lacking individual expression of mind in terms of style.

The hand of which version?

SOME OBSERVATIONS AS TO THE

PORTRAIT OF JULIUS II CONTROVERSY OF 2011ff.

ONE) The catalogue to the 2013/14 Städel exhibition

(Sander (ed.) 2013) deals with four versions of the portrait

of Pope Julius II by Raphael: the Städel version, the London

National Gallery’s version, the Palazzo Pitti version

(attributed to Titian) and the Uffizi version; the right ear

of the Pope is rendered very differently in every one of these

four versions, and this observation might lead to the question if,

for one, Morelli indeed got a point when comparing such shapes

of ears (even in portraits), and, secondly, to the question

if Morelli actually ever got taken seriously as to the comparing

of such details, since the comparing of ears did not play a role at all

in the context of discussing how these four versions might be related

to each other (while we have to keep in mind that Morelli never meant

to identify a painter’s hand merely on grounds of such isolated detail,

but regarded the collecting of such observations indeed

as the collecting of clues that might be looked at in context;

compare also chapter Visual Apprenticeship III, with the

presentation dedicated to ›Morelli and Raffaello Sanzio‹),

and we will also come back to the Julius portrait in Cabinet V.

TWO) If the Palazzo Pitti version is indeed to be regarded

as a copy by Titian after Raphael, one might be inclined to ask

if this on the other hand resulted with an imposing of

›Titianesque‹ anatomical notions upon the representional style

of Raphael who, on his part, had imposed his anatomical notions

upon the as-it-were veristic rendering of a real person.

THREE) Concerning the 2013 controversy one might also ask, if a)

the public, and also the European or even world-wide public,

actually did understand what the Städel museum exactly meant

by attributing the Städel version to ›Raphael and workshop‹;

and b) if the public also did get to understand that Raphael expert

Jürg Meyer zur Capellen had built his case to attribute a segment

of the portrait (namely only the Pope’s face) to Raphael himself

in a completely different way than Städel curator Jochen Sander

did built his case to attribute even larger sections

to Raphael (namely based on pentimenti, and partly also on

only assumed pentimenti); because Meyer zur Capellen who had,

on occasion of the acquisition of the portrait by the Städel, supported

the museum by an expertise, did not regard these pentimenti

found in the underdrawing of the portrait to be by Raphael,

but by an anonymous assistant

(compare Sander (ed.) 2013, p. 56-58 and 90ff.;

and compare our presentation here).

If now we would review the recent minor controversy about a portrait of Pope Julius II that, in 2013, was in discussion again, after the Frankfurt a. M. Städel museum had – in 2011 – claimed its version to be by by ›Raphael and workshop‹, we would have to describe a scenery of various art historical platforms, dealing with problems of attribution. The institution of the museum as the one platform, representing art history in the museum, and providing the public with a scholarly exhibition catalogue (Sander (ed.) 2013); while various media platforms, as well as various weblogs rather tended to challenge the new attribution brought forward by the museum, in support of the London version, owned by the National Gallery, being by Raphael and being the original, or discussing the Florentine version (or even the two Florentine versions in the Uffizi on the one hand, and in the Palazzo Pitti on the other). While again on another media platform a professor might intervene in favor of the museum’s claim.

On the whole one cannot help the impression that scientific connoisseurhip had not been unfolded as Giovanni Morelli had once imagined it to be unfolded in the future. Much of the debate focussed on the museum’s relying on pentimenti, interpreted as clues of painterly originaly (in its correcting, its changing of a composition revealing a mental process, not, or less likely to be expected from the work of a more copyist), and of this, certainly, Morelli at his day could know of less. While the rendering of hands and other details was also in discussion, ironically rather on various weblogs (already in 2011), but also an issue in the scholarly catalogue of 2013 (see for example p. 59 (Jürg Meyer zur Capellen)).

But all in all one might still be inclined to ask if the appropriate platform, certainly an online platform, yet is to be established in the future, a platform that would serve all the needs of scientific connoisseurship, as Giovanni Morelli had not been able to unfold himself, but could be unfolded, in developing an adequate visual management, layout and visual resources, and this to the mere benefit of learning.

Weblogs might also have their place on such a platform, and one or the other blogger might also point to the fact, that, while discussing the various versions of the Pope portrait, one had, if only occasionally, referred also to the name of Morelli (but unfortunately one had only repeated the old misunderstanding that he, allegedly, had claimed that painter could be recognized by the rendering of a hand alone; and this exactly had never been his claim, and this had exactly been the view that he had repeatedly dismissed himself (Morelli 1891, p. 4, note 1; Morelli 1893, p. 318 [reprint of Morelli 1882]); and if Giovanni Morelli had listened in into the 2013 debate, he might also have been tempted to upload the one or other page from his books, that had been dedicated to contribute something to a more in-depth discussion of the question how Raphael did represent hands, namely an ›aristocratic‹ type of hand, that, according to Morelli was one characteristic Raphaelesque feature that could be distinguished from other painters’ types of hands (but exactly these kind of comparison actually required a visual management to make such comparison comprehensible, that, at the day of Morelli, simply could only be dreamt of).

Nor an attributional method complete in itself, nor being a ›recipe‹ to be followed from step one to five,

but a recommendation particularly to be taken into consideration in situations like these:

who’s the Julius II by Raphael? Or: a visualization of the quintessential Morellian situation

(picture: staedelmuseum.de; Städel version with the two Florentine versions, one of which is given to Titian)

If now we would turn, in our little survey of conteporary connoisseurship, to Dutch art. To review the outcome of one of the larger projects in recent history of attributional studies, and in our wanting we might encounter one or the other Rembrandt scholar, warning us of crossing the boundaries between Italian and Dutch art. And one Rembrandt scholar might even be as polite as to warn us that the first volume of the famous Rembrandt Research Project indeed, if only briefly, had referred to the name of Morelli (Bruyn et al. 1982, p. XIVf.), but that the methodology of the whole project had been remained rather mysterious, be it, as to its earlier phase, or be it to is more recent achievements. Certainly, to do scientific testings of various kinds had been an ambition, but as to a culture of verifiability and a systematic unfolding of what could be contemporary style criticism, the Rembrandt Research Project, in spite of its many achievements, might not necessarily be the primary example to follow. At least not as to organizing, methodological consistency and transparency.

But perhaps it is just now the time to think about a general renewal, the Rembrandt scholar said also, seeming a little melancholy, but on the other hand not without some sneezing, about a general renewal and newly defining of what scientific connoisseurship (comprising all the various disciplines that have to be associated today with attributional studies) was all about. And recently also a congress at The Hague, had already been held, to discuss such and other matters. Giovanni Morelli and his approach, among other things, had also been an issue, and thus we may go on here in our survey, in quoting from one paper that had also been presented on that occasion, meant to recall, in taking a more broad view, what the quest for scientific connoisseurship, in the late 19th century, had been all about.

**

TWO) FROM THE MUSEUM OF METHODS?

»[…] the so-called science of connoisseurship has receded so far into the distance that it is hard to imagine a time when it seemed a new and invigorating mental exercise.«

Kenneth Clark (Clark 1960, p. 382)

›I delighted […] in your placing of P. POTTER as a landscape painter that high too.

In some of his pictures he seemed to be the most sublime of all Dutch landscape painters to me.

Perhaps no other of his fellow countrymen did know to apprehend the Dutch atmosphere that truly

and to render it that poetically as he knew. A great talent.‹

(»Es freute mich […], dass auch Sie den P. POTTER als Landschafter so hoch stellen.

Mir kam derselbe in einigen seiner Bilder als der feinste aller holländischen Landschafter vor.

Vielleicht hat kein anderer unter seinen Landgenossen die holländische Atmosphäre so wahr aufgefasst

und so poetisch wiederzugeben verstanden wie er. Ein grosses Talent.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 27 March 1882 (M/R, p. 217)))

It was in 1868 that Giovanni Morelli made a brief visit to The Hague. He was fifty-two years old at the time, unknown to a general public, and coming back from his first visit to London. One result of this trip was apparently that Morelli took a liking for paintings of Paulus Potter (which makes an interesting pairing). And as to scientific connoisseurship he was looking ahead to the future, since his ideas were still in the making. It was to take him six years more to appear on the scene and to do what a French art historian has called in retrospect (Damisch 1970, p. 169): a stirring up of the demons of connoisseurship for a longer time.

Giovanni Morelli’s turn to connoisseurship occured very late in his life and only in the second half of the 19th century. And this century had already seen several developments: historical studies had developed towards a science; archival research had become common, in art historical studies as well; connoisseurs with painter’s skills had developed a sense for painterly techniques of the old masters and their materials; and connoisseurship in general had a subjective and intuitive, but also, if informally, a very rational side. To understand Morelli as a connoisseur it is crucial to be aware that he took this whole eclecticism of method that made the attributional studies of his time more or less silently for granted and that he did not mean to replace it, but wanted to carry on with most of its elements (even if he sounded at times more like a revolutionary), and with some new.

Widely considered today as a distant relative of Sherlock Holmes, Morelli seems to represent the triumph of rational thinking and minute observation and not respecting pretensions. But the actual reason why he had began to think about method had been, as he later admitted, his own unsecurity. If he passionately strived to enthrone his own method this is more the proud showside of a fundamentally sceptical individual who was actually much more concerned to enthrone the aspiration for a higher level of certainty in matters of attribution as such, whatever strategies it may require. In brief: the whole traditional eclecticism of method was fine – but for a sceptical individual like Morelli it was not enough. There had to be more. A higher level (or quantity) of certainty, to reduce the uneasiness of someone who could be passionately optimistic for moments. but who also never lost his selfdoubts. And this is not a heroic beginning of scientific connoisseurship, but it is the truth. In the beginning were self doubts (compare GM to Jean Paul Richter, 21 May 1885; referring to c. 1860), and Morelli’s followers, those who really knew him, were occasionally surprised, if not shocked, to hear their revered master belittleling his own achievements.

Morelli had, as was widely acknowledged, great qualities as a man. He was most cheerful, cordial, had a strongly developed, waggish sense of humour and was much loved by his friends. And as a connoisseur, one might say, it was probably and paradoxically one of his qualities that he had and admitted doubts, which, as it were, as a driving force constantly did question his certainties and required this higher level, this ›plus of certainty‹.

Paesaggio rupestre con animali by Roelandt Savery,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

As the first main reason why to come back to Morelli, why to portray him with eyes of today, one might name the fact that he represents the ambition to speak of connoisseurship in terms of science. This was not new as such, but this speaking had all the implications that the notion of science could have at around 1880, when German speaking art history as an academic discipline was in a phase of reorganisation after the first international congress held at Vienna, and while connoisseurship was rather a practice in and outside – or inbetween – the institutions. And this fragmented, little organised and often intransparent field of practice was suddenly confronted with the idea that there could be a new standard, a new level of certainty attainable, a gold standard, seemingly guaranteed be a new tool, but also a standard, possibly becoming the standard for everyone else, in and outside the institutions, and thus challenging everyone else. The kind of idea to produce all kind of tensions and unrest, and it did stir up the demons of connoisseurship, apart from the question how useful, how reliable or how prone to error this new tool turned out to be.

Now: What exactly did Morelli himself understand by science? How would a Morelli inspired checklist as to what scientific connoisseuship was (or is) about look like?

One should name in the first place, and as to the procedural side of science, that Morelli thought that connoisseurship should be organized as a mutual exchange of rational reasons, based on clear theoretical assumptions (and not as a mere competition of authoritative claims), thus a shift from mere claim to its justification; one should name further the ideal of transparency of method; and at least mention that Morelli thought of the institutional side of science as well, if he envisioned a future science of art that was built on connoisseurship and thereby assigned a fundamental value to attributional skills (instead of seeing the connoisseur as a more or less welcome guest, usually coming from a different social world, to be located somewhere inbetween the institutions). Morelli thought this future science to progress, which might include at least the establishing of an institutionalized culture of self-reflection and an institutionalized memory, in that a science can only progress if knowledge and experience is accumulated and not held exclusive to small circles. And the idea of thinking connoisseurship as a scientific community implies as well the ideal of permanent exchange of information (if not to use the fashionable term of ›open access‹). In short: Morelli was not only looking ahead to the future, when briefly visiting The Hague, but generally, and certainly he did consider his project as unfinished and open (while his intellectual heirs tended to either change this project or to consider it as finished by focussing only on pragmatic application). Thus Morelli is representing the very contemporary question to what degree a culture of connoisseurship could or should define itself as a scientific community with clear ideas of rules and standards, be they minimum or maximum standards of quality.

But if Morelli did raise these questions, it does not mean that he presented final answers. A Morelli inspired checklist has its limits and its peculiarities as well. One might ask if a sense of humour does belong to science, and we see Morelli nod and say decidedly ›yes‹. Thus we have to live with the confusions that his ironies and practical jokes did cause (a delicate thing for a foundational figure, but he did enjoy to cause a little confusion here and there).

But speaking of virtues and vices, one should mention above all what is really lacking on this checklist. And this is the criteria or demand of a real systematic representation of knowledge and, above all, its genesis – but this is exactly were his mission ended. Not because he would not have accepted this criteria by principle. It is again something very human and rather trivial that Morelli, who did inspire his pupils to speak of system-building and objectivity (words he never used), most deeply hated to be pedantic in a formalistic-systematic way. He simply had no patience, no persistence, no discipline for expertise in form of accurate protocols of certainties and doubts, for oeuvre catalogues or comprehensive histories of painting (his literary genre being the countercatalogue (compare Penzel 2007, p. 294), the counterattack). His pupils did complain, but this did not help. And it’s a real irony of history that someone who has become an embodiment of minute obervation and rational thinking most deeply hated to be pedantic in a formal way. If Morelli did represent the 19th century of system-building and scientific progress, one might say that he is also representing the 19th century that had no patience to work systems out. And his heritage is not the least a difficult one, just because Morelli did not fully live up to his own ideals, and because he does at the same time represent a new culture and to some degree an old culture, that he meant to renew.

Paesaggio con boscaioli by Jan Tilens (e aiuti),

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

Marina con pescatori e barche by Jan Josephsz van Goyen,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

A second major and probably the classic reason to come back to Morelli might be the fact that he is representing the ambition to rethink applied style criticism. Be it for the sake of reassessing the pragmatic value of a certain tool or for the sake of reassessing what applied style criticism can do at all: with or without Morelli, digitally equipped or not. Although sceptical Morelli had predicted that his name would be forgotten two years after he had died, his ideas have found their way into the digital age; and it seems only a matter of time until the Morellian method, this old silk hat from the museum of methods, resurfaces digitally equipped. Hence: It might be useful to briefly point to a few neuralgic points that have always caused or still are causing difficulties and confusions.

What is known as the Morellian method can simply be thought of as a recommendation to work with a certain class of visual properties, which Morelli called ›characteristic‹ properties. ›Characteristic‹, in this respect, had a special meaning which was often more felt than really acknowledged: it meant ›exclusively characteristic‹, exclusively found in one painter’s oeuvre only. And what resulted was a very suggestive logic of, one might say, biometrical suggestiveness, that seemed to meet the desire for simplification: if found in a work in question a property could be seen as the ultimate link a certain oeuvre. Property found and problem solved.

A common misunderstanding it is however to think that Morelli thought these properties to be stable and recurring in perfectly identical shape, as it were: in literal repetition. This is not the case, although oversimplified and ideological interpretations have suggested exactly this. But for Morelli it was not about a perfect matching or not matching of characteristics. He worked with the notion of type, and the basic operation was to ask, if a shape in question could be interpreted as the realization of a certain type, the type being a mere mental image, derived from a great number of examples. The allknown shapes of hands and ears from the tables in Morelli’s books, often misunderstood as precise representations of characteristic properties to match, represent in truth attempts to visualize this type in idealized form and not shapes that one should expect to recur in perfectly identical repetition as stereotypes. Because in reality the type shows variability like a signature and not stability like a fingerprint. The fingerprint metaphor, a hard science inspired language and a repressing of the fact that acts of interpretations are involved – these are all clues for very ideological interpretations of Morelli, much exaggerating his method’s validity and therefore its pragmatic worth and thus another demons that Morelli undoubtedly did stir up as well.

A second source of misunderstanding bears on a general overlooking how modestly Morelli actually assessed the pragmatic worth of this testing for characteristic properties as a tool: apart from the fact that he did calculate with the possibility that these properties could be copied, he explicitly and repeatedly denied that attributions should rest solely upon this testing, but remained rather unheard. The Morellian method – for Morelli himself, who seemed to consider its suggestive logic as something rather dangerous – was meant to be used in combination with other tools, any tools, and especially one tool that is not exactly generally associated with Morelli, because, again, he did rather take it for granted: intuition, intuitive judgement and and all it involves.

It is a third recurring misunderstanding, that results from isolating the Morellian method from the whole of Morelli‘s working methods, to think that Morelli represents a merely objectivistic position. While in truth he is representing an interesting compromise between a subjectivistic and objectivistic position, since at the moment the Morellian tests, this checking for characteristic properties were applied, intuitive assessment had already been at work and, as it were, exhausted its limits, but narrowed the field. As a prescientific tool, one might say, but encompassing all that intuition embodies, subjective sensitivity, sense of quality, long experience and memory capacity; a very welcome tool for Morelli to find hypotheses. While the Morellian method was meant primarily as a testing aid. Hence intuition and subjectivity Morelli certainly did dethrone, but he did not dismiss them at all (as tradition often, but falsely has it). And this makes again a slight difference of important weight, if it comes to the question of the status of various tools and the question whether to mystify (or even re-enthrone) subjective sensitivity and intuition or not.

All in all Morelli was a rather difficult founding father of method. Eagerly he did observe his various disciples trying to apply his recommendations in practice. Rarely joyfully, in general rather mournfully and melancholy, on the whole: rather silently.

His disciples, on their part, did observe him. And while this whole scenario of mutual observing is not lacking elements of comedy, I would name this the third good reason why to come back to Morelli today: just because he left his disciples with numerous alternatives and difficult decisions to make, and forced or invited them to think for themselves. As another analytic tool, a sort of system of coordinates, and also as a general summary one might name some of these alternatives that were to shape the future directions of connoisseurship after Morelli.

**

THREE) A MORELLIAN VISION

›In another study right beside it

a painter rode on a Raphaelesque hobby-horse

and traced nothing but legs and ears in old pictures.

He was a famous master too, since he carried a large

retinue of pupils with him.‹

·····························

»In einem anderen Atelier dicht daneben

ritt ein Maler auf einem raphaelischen Steckenpferde

und decalquirte Nichts als Beine und Ohren auf alten Bildern.

Er war ebenfalls ein berühmter Meister, denn er schleppte

einen langen Schweif von Schülern mit sich.«

(picture: molochronik.antville.org;

text: Grandville [1979], p. 94;

originally published, in French, in 1844)

The probably most basic choice a follower of Morelli had to face, not without an ethical component, was certainly to decide whether to commit oneself to a future science of art and thus for a collective enterprise being of general interest, or just to focus on the pragmatic usefulness of a certain tool in one’s particular and usually short term interest.

This affecting the question whether to think of method as something ready to be applied or: as something constantly to develop, to expand and to improve (for example in terms of protocols, especially visual protocols, but also in terms of appropriate language to describe visibility: two problems Morelli was much concerned with during the last years of his life).

Morelli’s followers faced choices whether to learn from their master’s virtues or vices; whether to listen to his optimistic or to his fundamentally sceptical self, that would suddenly and shockingly declare that maybe ›everything was just illusion‹ (Morelli 1891, p. 5f.). Whether to learn from what Morelli explicitly did recommend, or from what he rather silently did take for granted; whether to become a specialist or rather an eclectic generalist (or at least someone able to cooperate and to organize help if needed).

And to name one fundamental choice that bears on the mentality inherent to applied style criticism as such: whether to re-enthrone intuition as the pivotal tool (and to consider further testing of hypotheses as pointless, at best explanatory and, potentially, as undermining the authority of genius), or – like Morelli and maybe more compatible with contemporary mentalities – to regard intuitive judgement more as a shy beginning of any process to determine authorship and not as its self-opinionated end.

Apart from all these alternatives and many more – to deal with Morelli’s ironies was, last but not least, one of the most difficult tasks that whoever wanted to be a Morellian had to face, and here is just one example:

In 1874, six years after visiting The Hague, Morelli heralded a classic era of applied style criticism with a number of provocative essays. But it is striking and maybe surprising that the first of this essays speaks briefly and in passing by also of chemical analysis of painting and this in a very peculiar way. It is one of Morelli’s characteristic attacks on the pretentious other connoisseur, his favourite enemy, who, in his view, did claim to be capable of chemical analysis of painting just by using his eyes. Morelli, who did witness some of the beginnings of technical art history and who is showing his eclectic side here and obviously is again looking ahead to the future, does not dismiss the chemical test as such. What he says implicitly and unexpectedly is: Ridiculous the kind of chemical analysis that is done by eye alone (Morelli 1874-1876, p. 8; Morelli 1890, p. 96).

***

A gold standard of attribution? (picture: theguardian.com)

Vulcano by Francesco Raibolini detto Francia (e aiuti),

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

FROM A MORELLIAN CHECKLIST TOWARDS A RENEWED MORELLIAN VISION

(ONE) A BASIC ALTERNATIVE: CONNOISSEURSHIP THOUGHT AS EITHER ART OR SCIENCE

Connoisseurship, if understood as a field of human practice and equalled with attributional studies and above all the practice of attribution (or determination of authorship), can be described either in terms of an art or a science (compare Locatelli 2014). If one thing is certain, then it is that Giovanni Morelli did regard connoisseurship not only as an art, although, for many years, he might have only practiced attributioning, without reflecting upon whether it might be seen as an art or a science. But Morelli, in hindsight, does represent the claim and the ambition that connoisseurship could be developed into a science. And that the science of art (perhaps to be equalled with art history as a discipline, or with a more systematically and less historically operating Kunstwissenschaft as a discipline) should rest upon (scientific) connoisseurship, which Morelli expressed by using the formula, saying that every art historian had also to be a (scientifically operating) connoisseur.

None of his rather small number of pupils, though, took this claim very seriously, and the Morellian ambition has actually to be recalled, since no Kunstwissenschaft, based on his understanding of connoisseurship, did ever evolve (although every art historical discipline is and remains based on attributional studies of whatever kind, on connoisseurship, in brief, whereever and however it may be practiced, and also, usually on an ad hoc basis, within the academia, while, all in all, connoisseurship as a practice has never been fully integrated into academic art historical disciplines on more than just an ad hoc basis).

Thus it can be named as the most basic alternative that an apprentice connoisseur might face, to either commit to a science (thought of as a collective human enterprise, organized by a scientific community), or to commit to a practice that might serve him or her in whatever circumstances (and indirectly perhaps also the scientific community or society at large). Which does not mean that scientific connoisseurship would have no relevance in the practice of an individually operating connoisseur with no claim to apply scientific standards (for example as to standards of certainty), but the commitment to a science is hardly fully compatible with the individual practice of attributing in service of the art trade. Those who knew this best were Morelli’s two most ardent followers, namely Jean Paul Richter and Bernard Berenson, who both chose to leave the vision of a Kunstwissenschaft that would rest on scientific connoisseurship behind, and certainly, if not only due to that reason, also due to the reason that their way of practicing connoisseurship was not compatible with scientific standards such as transparency or verifiability.![]()

(TWO) THE INSTITUTIONAL SIDE OF SCIENCE

Since a culture of scientific connoisseurship never unfolded within the academia, it is here about to name what the vision of a institutionalized culture of scientific connoisseurship would imply: a culture of theoretical self-reflection as to an intellectual framework and as to practices (and also as to continuously updated standards and best practices, including a reflection upon how to deal with what remains unknown in processes of attribution, i.e. how to deal with doubts and uncertainties), an institutionalized memory (i.e. a knowledge as to the history of connoisseurship), and thus: an accumulation of knowledge as to the experiences accumulated within this history of connoisseurship, accumulated by individuals (or groups), theoretically and practially (be it that such knowledge has yet been transmitted or not), moreover a solid knowledge of methods, tools and aids, of shortcomings of methods, tools, and aids, and also of test cases and historic failures, also serving the scientific community of an (imaginary) art historical subdiscipline to progress and to built also on such experiences into the future (instead, as it is common now, only now and then to come back to only fragmentarily known experiences). No journal, one might recall as well, has ever been exclusively dedicated to the history and theory of attribution, serving the needs, also in surveying contemporary developments, of a multidisciplinary progressing field of practices.![]()

(THREE) THE PROCEDURAL SIDE OF SCIENCE

Scientific connoisseurship does, by principle, not accept the authority of mere authoritative claims as to the determining of authorship, but respects the authority of plausibility, that is: of good reasons brought forward by whomever, but explicitly. This does not mean at all to dismiss intuition as being a part of human practices, but claims based on intuition would have to be regarded as mere hypotheses, not yet explained or backed up by reasons (which can also be regarded as a problem of language).

Scientific connoisseurship hence is or would be in need of an appropriate language, expressing how observations have come to turn into arguments (formal analogies as far as style criticism, thought of as a subdiscipline of connoisseurship, would be concerned); but as much the use of language is important within a culture of verifiability and transparency of method, as important is/would be a culture of visual management, not only able to show comprehensibly, on what visual analogies claims as to authorship are based, but also able to show, why certain observations as to stylistic regularities deserve to be regarded as being more substantial than others (such as for example mere single, and perhaps just incidental likenesses). This bears on the problem of common standards (including standards of exchanging informations), constantly reflected upon within a culture of self-reflection, but respected by a scientific community.

And if such standards would be implemented, (concerning for example the use of protocols, guidelines of methods, set up for various fields of practice) one might also think of scientific connoisseurship, though without being institutionalized in terms of an organized discipline, yet organized – and in some sense insitutionalized – by a common complying to such standards, thought as being institutions.![]()

An allegory of connoisseurship? – ›The old wise hermit, who had been thinking of no harm, sees himself all of a sudden encircled and threatened by the devil and his accomplices. Anthony, however, does not lose his composure, but immediately has the pitfalls of the hereditary enemy taped, and thus does look, undauntedly, indeed confident of victory, into his hideous face. Isn’t he, here, to compare with, in his threatening position, for instance with the sharp-eyed and competent art scholar, who does know, with certainty, to avoid the pitfalls that crooks and frauds, on all routes and all paths, aspire to put down for him, be it with fake cartellini, be it with Flemish copies?‹

···········································································

»Der alte weise Klausner, der an nichts Böses dachte, sieht sich hier plötzlich vom Teufel und seinen Helfershelfern umringt und bedroht. Antonius verliert jedoch keineswegs seine Fassung, sondern durchschaut sogleich die Tücken des Erbfeindes und blickt ihm daher unverzagt, ja siegesbewusst ins Fratzengesicht. Ist er hier in seiner bedrohlichen Lage nicht etwa dem scharfblickenden und sachkundigen Kunstforscher vergleichbar, der mit Sicherheit den Fallen zu entgehen weiss, welche Gauner und Betrüger auf allen Wegen und Stegen ihm, sei es mit den falschen Cartellinos[,] sei es mit vlämischen Copien, zu legen trachten?«

(Source: Morelli 1890, p. 356 (my translation; the passage has been omitted in Morelli 1892; compare pp. 271ff.); Morelli: Liberale da Verona; Crowe/Cavalcaselle: Bernardo Parentino/Parenzano; see p. 357 of Morelli 1890)

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH PART II:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet I: Introduction

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet II: Questions and Answers

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet V: Digital Lermolieff

Or Go To:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | HOME

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Spending a September with Morelli at Lake Como

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | A Biographical Sketch

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Visual Apprenticeship: The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Connoisseurial Practices: The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | The Giovanni Morelli Bibliography Raisonné

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | General Bibliography

Cabinet I: Introduction

It does not make things easier, curator Stephan Kemperdick said in 2006, that Hans Holbein the Younger, as his father – and as his Basel master Hans Herbst – signed with his initials HH (Kemperdick 2006, p. 12). But on the other hand, Hans Holbein, if it is also true what Kemperdick says as to the artist’s rendering of hands and noses, seems to be an ideal test case to apply the Morellian tests and controls. If, one might add, if the Morellian culture of applied style criticism would be still alive and well, Holbein might be our possible test case.

But is, we must ask, and yet in and with this introduction, is Morellian connoisseurship alive and well at all (and has it ever been, since it was meant as a project, to be developed in and into the future)?

Or has it rather sunken into half-oblivion (never having been developed further, as Morelli actually had wanted it to be developed)? While Morelli, nonetheless and without any doubt, has become a symbolic figure. Symbolizing a decidedly rational approach to attributional studies.

But this on the other hand, might be an all too narrow view of Morelli. And with this introduction to our studiolo, we should like to take a broader view, in introducing to our discussion of the connoisseurial practices of Giovanni Morelli, and with giving a sketchy portrait of his intellectual approach. And with suggesting a renewed vision in the end, a compass, designed to recall and to clarify what scientific connoisseurship, at the day of Morelli, was all about and thought to be. And what it might be in the future. To every connoisseur to find out if he or she could be regarded as working in the Morellian tradition or not.

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship III

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet I: Introduction

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet II: Questions and Answers

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet V: Digital Lermolieff

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS