M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY Cabinet II: Questions and Answers  Rudolf Friedrich August Henneberg, Wilhelm Bode als Jäger (1868) (source: haum.info/dib) |

Some of Morelli’s followers and friends found that his teaching was not exactly a systematic teaching and they were right. Neither was Morelli inclined to equip every opponent with his skills, nor was he inclined to expose himself more than necessary, and he did expose himself, but more in style of giving examples, and not in being systematic in a rigid sense (in other words: he did not expose himself systematically, as his own intellectual approach, as scientific connoisseurship, actually does demand it).

Questions and Answers

What we are attempting to do here is to stick to a compromise between rigid system-building and mere unsystematically improvising essay-style. We try to assemble, in a coherent way, questions as to Giovanni Morelli’s connoisseurial practices. And we try to answer them as concise as possible, which, in some cases, means that we have to speak concisely about Morelli not being concise, nor systematic, nor decided.

And this cabinet, the core of the second part of the Giovanni Morelli Monograph, is meant to develop as a platform of its own kind. Assembling not only the most important basic questions, but also materials that, ideally, might inspire further study of style criticism and of connoisseurial practices (and hopefully also some innovations). Which we consider to be worth pursuing, not only because it is about attributional studies, but because it is about visual apprenticeship, visual education, and, in brief, about looking and interpreting as such, its problems, ambiguities, its sensual side, but also its intellectual side, in a word, about a possible opening of perspectives onto more than mere attributional studies, but on the world and on human nature. As human ways, the human nature and the human condition do show, to the best or to less than the best, also within the narrower boundaries of attributional studies.

CABINET II: QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

(A) GENERAL QUESTIONS

(B) THEORY AND PRACTICE

(C) HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

AND (INSPIRATIONAL) POTENTIAL

AS FOR TODAY![]()

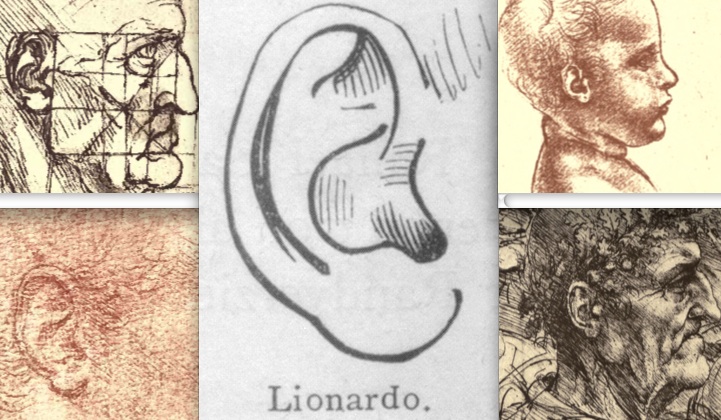

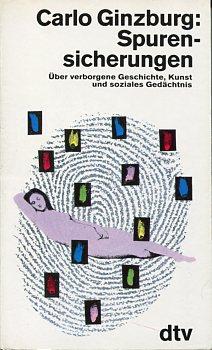

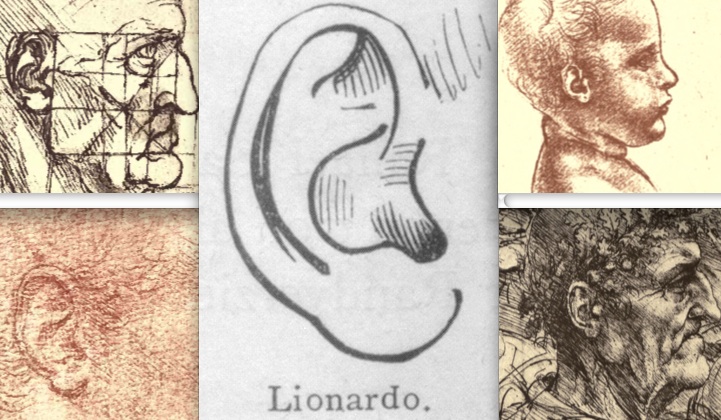

›[…] the proof was virtually absent in my essay on clues. The series, on the other hand, was well present, but as a pure fact, not analyzed critically. For example I emphasized that Morelli identified clues that interested him as differentials within homogeneous series, made of painted nails, ear lobes depicted, etc. … but I was not discussing the procedures that could have led him to a constructing of such series.‹

»[…] la preuve était pratiquement absente de mon essai sur les indices. La série, en revanche, était bien présente, mais comme un pur fait, qui n’était pas soumis à l’analyse. Par exemple, je relevais que Morelli identifiait les indices qui l’intéressaient comme des écarts différenciels à l’intérieur de séries homogènes, composées d’ongles peints, de lobes d’oreille dépeints, etc. … mais je ne discutais pas des procédures qui avaient pu le mener à construire de telles séries.«

Carlo Ginzburg (Carlo Ginzburg 2007, p. 41)

A) GENERAL QUESTIONS

1) Which is the primal and most widespread misunderstanding concerning the Morellian method?

Has Machiavelli been a Machiavellian, Kant a Kantian, Darwin a Darwinian, or Freud a Freudian?

In our more modest context, though, it is about the question if Giovanni Morelli has been a Morellian (as the term is widely understood). And we state that the primal, the most frequent misunderstanding as to the notoriously famous Morellian method is to equal Morelli’s practice as a connoisseur of art with a mechanical, isolated and narrowly understood application of the so-called Morellian method.

In a word: we state that Morelli has not been an orthodox Morellian (as the term is widely understood); but also that such an (wrongful) impression might result from a superficially reading of mostly theoretical texts (text on Morelli, as texts by Morelli himself). But immediately dispels, if Morelli’s actual connoisseurial practices are put under scrutiny. And by this we do not mean, for example, to just ask (in an all too general way), if Morelli was ironical, or dishonest, or sometimes equivocal. But it is done justice to Morelli in that we ask: what exact argument did he put forward in the individual case (chapter three on expertises does discuss three cases in detail)? Because in its core the Morellian approach to connoisseurship meant that arguments had to be brought forward. Which also means that it was and it is not about the debating of mere general impression alone (as to a painting in question, or also, one might add, as to the actual proceeding of a connoisseur of art). Also about a general impression, but not alone (compare Morelli 1891, p. 4, note 1).

[the primal misunderstanding as we do call it here, to think of Morelli as an orthodox Morellian in a cliché-laden sense, exists in various variations; for example it does exist as the (wrong) belief that Morelli ›recognized painters by the ear lobe‹, that is that he allegedly had said/thought that paintings could be attributed by looking at such details as hands and ears alone; because exactly this he might have sometimes (unintentionally) suggested (for example in Morelli 1880, p. 2), but knowing of this misunderstanding he explicitly did state the contrary: that it was not about the attribution of works of art, based on such pointing to Morellian detail alone; also, but not alone (compare again Morelli 1891, p. 4, note 1; and compare the even earlier statement: Morelli 1893, p. 318 [reprint of Morelli 1882]); and one might also say that another variation of the misunderstanding consists in the taking of a working with Morellian detail out of its respective context; another misunderstanding, one may go on to proceed, consists in that it is often thought that the Morellian method was to be applied as such in any context; while, in truth, its reasonable application had meant to be limited to very specific contexts (see introduction); nonetheleses, and naturally, one might also ask, if the use of the Morellian method could also be generalized, in a sense that one could work with Morellian details reasonably in various, and maybe also in any given context (compare also answer to question 11)]

[for most important thoughts about ›mythology of doctrine‹ (inspired by Quentin Skinner) see Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 222]

[rightly sceptical observers, by the way and in spite of their also being under the spell of the misunderstanding, have referred to Morelli’s methods as being, occasionally, ›the least Morellian which there could possibly be‹; see Haskell 1978, p. 86: »les méthodes les moins morelliennes qui soient«]

[as to another primal, or second primal, or the second primal misunderstanding see question No. 15 below]

2) How does one attain a comprehensive picture as to Giovanni Morelli’s connoisseurial working methods?

Paesaggio rupestre con figure by Pietro Montanini,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

One may think that the best way would be to read Morelli’s own books, but we do recommend here rather a more diversified approach. Since Morelli did not show to be inclined to reveal systematically every reason that his attributions were based upon in his books. He did so in some cases (compare again chapter on expertises), but if one does look more systematically for a Morelli being inclined to put all (or most) of his cards on the table and to reveal his argument more fully, more frankly than he might appear by just checking his published books, one does find this Morelli also and rather occasionally in his books, but more so in letters to his pupil Jean Paul Richter, who over many years was the one pupil Morelli liked and did enjoy also, in a more relaxed way, to discuss attributions and reasons for or against certain attributions more frankly that he did discuss attributions or deliver expertises in his books (Jean Paul Richter himself was also aware where exactly in his books, Morelli had revealed his practices more fully: see Seybold 2014a, p. 70, note 163; and compare Morelli 1890, pp. 258ff.).

This being rather inclined to secrecy, of course, could and has also to be criticized, because Morelli’s approach to connoisseurship implied that reasons had to be put forward and arguments had to be revealed fully and transparently (compare Morelli 1890, p. 42; Morelli 1891, p. 16; M/R, p. 75). To guarantee a culture of verifiability and, in a modern sense, falsifiability. But it is fair to say that Morelli himself not always, not at all time, and not at all in every single case, had lived up to this implication of a wanting to establish a culture of scientific connoisseurship (although Morelli was in the habit of reminding his readers occasionally (or his pupils), that it was about putting forward of rational arguments).

[as the more symbolical expression of Morelli not being inclined to lay all of his cards on the table might be seen that he enlisted, as in the case of Giorgione, distinctive properties that he did consider to be characteristic for Giorgione, but stopping to enlist these properties all of a sudden, by saying simply ›etc.‹ (namely »u. s. f.«; Morelli 1891, p. 280), as if it was clear in itself what he was talking about, or if one was meant to find out on one’s own, on what exact reasons Morelli had based or was basing his Giorgione attributions; and in a sense, that is, actually, one was indeed; and perhaps to the benefit of practicing more intesely to think like Morelli might have been thinking (he had for example chosen to dismiss the again naming of a characteristic Giorgionesque cloud; compare Morelli 1880, p. 196f., note 1), but not necessarily to the benefit of a better, more transparent and concise understanding of Morelli]

3) Is there a concise definition of the so-called Morellian method (being understood here as being part of a wider set of connoisseurial working practices)?

San Bonaventura nello studio by Pseudo Giovenone,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

Giovanni Morelli recommended to check a work in question for sets of properties, thought of as being characteristic for certain painters, to attain in the end, also relying, but not solely relying upon such tests, a higher degree of certainty than was, in his eyes, to be obtained by checking a work in question merely intuitively, or by relying solely on documents.

[This one-sentence definition of the Morellian method, in spite of its shortness (or length) refers actually to a set of practices that could also be thought of as a five stage process: a) definition of a problem from with an intellectual framework (guiding further actions results, be it in the field of style criticism or in any other area of connoisseurship, which is historical studies, more specific (interpretive) art historical studies, or material tests); b) it is about to have, i.e. to know about characteristic properties of relevant painters (which is also referring to an ever ongoing process of gathering (knowledge, visual knowledge as to) such properties); c) it is about observing/finding formal analogies upon which an argument can be built; d) it is about to assess the worth of such observations in context (the weight of arguments, some of which being more substantial than others); e) it is about to make such arguments, within the context of a complete assessment of the situation as a whole, comprehensible, i.e it is about to tell about and to show convincingly, upon what exact stylistic regularity one is inclined to base one’s judgment, and why one is inclined to give what weight to what detail (which means that one also has to show that an alleged regularity indeed is one (and not only, for example, a simple likeness without having any value as a distinctive, relatively distinctive or, ideally, exclusively distinctive property)]

[the above one sentence definition can be regarded as being based on the recommendations given in answer to question No. 2, and it can also serve as a backdrop to go back to Morelli’s own introducting of his ideas, namely in Morelli 1874-1876, pp. 7-10 [1874]; again in Morelli 1890, pp. 93ff., the latter volume also comprising his ›methodological causerie‹ Princip und Methode; from there one may start to collect also all the scattered statements in other volumes, particularly prefaces to other volumes, and also translations, and statements in letters, publications of pupils etc.]

4) On what kind of stylistic marks or properties did Giovanni Morelli focus (when applying his method)?

On a level of individual artists Morelli distinguished two separate classes of properties. But his approach will become more transparent, if we are going to speak about three basic distinctions at first:

1) Morelli made a distinction between properties that were common to groups or schools of artists (›school‹ referring to either artists literally working together or, in a more broad sense, like in ›Lombardic school‹, to whole regions), and properties that could serve to distinguish individual artists, that is: not found in whole groups, but only in individual artist’s oeuvres. Common properties he also did refer to as ›Familienzüge‹, ›features common to a family‹ (see Morelli 1880, p. 9), more metaphorically using a terminology rather being associated with the natural sciences, but in doing so, applying this terminology to art and indicating a thinking in analogy.

For Morelli the paradigm of a hybrid artist:

Francesco Ubertini, named Bacchiacca

(shown here a Saint Sebastian and

The Preaching of Saint John the Baptist)

2) On a level of individual artists Morelli made a distinction between artists with a distinct or strong artistic personality, and artists being less or not equipped with such a distinct mind, thus being rather imitators or epigones (or ›hybrid‹ artists, ›Zwitterkünstler‹, as Morelli also used to name them, and as one example of such a hybrid artist he did explicitly name Bacchiacca; see Morelli 1890, p. 131).

3) As to artists with a distinct artistic personality Morelli made a distinction between properties wherein this artistic personality, the artist’s mind, did show (and these properties included the famous types of hands and ears, the individual imprint, as it were, that the distinct artist’s mind left upon anatomical form, while representing anatomical form), and properties that he regarded as being rather accidental, more habits of the hand (mannerism; ›flourishs‹ like the ›flourishs‹, i.e. ›Schnörkel‹ of a handwriting) than of the mind (see Morelli 1890, p. IX, 58, 68, 94f., 122 etc.; Morelli 1891, p. 7, note 1; Morelli 1893, p. 361).

If Morelli was now confronted with the archetypical Morellian situation, which is: with the problem to distinguish closely related styles, he checked for these two classes of properties. Assuming that, if a work in question was by a master with a distinct artistic personality, this personality would show in the general impression, but also – and at this point the Morellian method comes in, helping the searching mind of the connoisseur – also in his characteristic properties (and thirdly: in his habits of the hand).

If, however, the general impression left room for doubts that the work was indeed by a distinct artist’s personality, if also an individual work did not allow for a checking of known characteristic details, the connoisseur could also shift his or her attention more to the habits of the hand. Because, as Morelli was assuming, a copyist would neglect the exact copying of marginal detail (a lacking of such detail, thus, could also serve as a clue); and an artist without a distinct artistic personality could also show his own characteristic habits of the hand (even if lacking an own artistic personality), which were, according to the Morellian taxonomy, not an expression of his mind, but accidental. But still, possibly, something to built upon one’s reasoning.

If Bernard Berenson was, later, to argue that, the more important the artist was, the lesser important the Morellian detail, this was nothing but putting in other words: if there were no such thing as a Morellian situation, there never would have been a need for a Morellian method to be applied, because Morelli had never made a case for a attributional method, to be applied generally, as such. And if his attention shifted between two classes of properties and also a general impression, it did show that Morelli did evaluate artistic personality in a more broad sense and in the most narrow sense, as good as possible, calculating also with the possibility that properties, actually expected to be characteristic for one individual artist only, could also be copied (compare M/R, p. 214, with Morelli referring to a Leonardesque ear in drawings that were, in his opinion, copied after Leonardo; compare also Ffoulkes 1911b). And if this seemed to be the case – all the more important it was to avoid a schematic and mechanical proceeding, and to prefer a constant re-evaluating of a situation. Which could also mean: going back to a new evaluation of artistic personality and: of general impression.

What might seem to be rather theoretical, or to be even of theoretical importance only: the distinction of various, which is: two classes of properties, is actually of a very practical revelance. Since the distinction of these classes, as the other two distinctions mentioned above, helps to tentatively evaluate and to define deliberately a problem at hand. And depending on how a situation might be defined, or newly be defined during the attributional process, a proceeding might be organized, or changed, and newly be organized. In other words: theoretical assumptions with what kind of problem one is dealing with, do organize the connoisseurs proceeding, in that these assumptions open perspectives on possibilities to work with, respectively help to focus on properties to check. And the three distinctions mentioned above might help to direct one’s research, rationally, into one or the other direction. To look for reference materials to compare the central work in question with other works, already named, and to more deliberatly organize comparisons, as flexibly as needed, including changes of perspectives and alternative tentative definitions of the problem at hand. Thus the Morellian method, understood as a testing, is not to be regarded as a linear method, proceeding from step to step in a mechanical way, but rather as a frame of reference, that allows to adjust the exact proceeding to the individual problem at hand.

[examples for characteristic properties are easily to be found in Morelli’s books, since all anatomical shapes that he worked with do belong, by principle, to that class of properties; his speaking of painter’s anatomical ›defects‹ might cause some confusion, since it is strange to think of defects as the outcome of great artist’s minds, but this term, occasionally used by Morelli for example in relation to Titian or Perugino, is probably to be understood in its referring to an (in itself irrelevant) academic naturalism, accurate in terms of anatomy, that, here, serves Morelli as a measure and enables him to speak, for example, of Titian’s exaggerated ball of thumb as a defect (and characteristic property, not to be found in other artist’s works); examples for habits of the hand can be found in Morelli’s enlisting of properties in relation to Bacchiacca (Morelli 1890, p. 131f.; a particular type of light grey rock, a type of hand with pointy fingers, a city with many towers, predilection for the color blue, etc.), since this painter Morelli regarded as an hybrid artist, not characterized by a distinctive artistic personality of his own, which, literally, does not leave room for characteristic properties in terms of an expression of the artist’s mind: all enlisted properties, thus, must be interpreted, in consequence, as being habits of the hand (although, one might add, a type of hand would rank here among the habits of the hand and not among characteristic properties, being an expression of the artist’s mind); Morelli does also discuss ›Schnörkel‹ at lenght in Morelli 1893, pp. 361-364 [reprint of Morelli 1887], as regards Pinturicchio and Raphael]

[at the beginning of a melting of the two above named classes of properties into one (more vaguely defined) class is, by the way, German art historian Anton Springer; and Morelli did notice this, not to his liking, himself (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 November 1881), referring to this kind of simplified reinterpretation as ›superficial‹; nonetheless this tendency of simplifying Morelli or of confusing the classes can be observed throughout the 20th century as well, with few art historians, like for example Henri Zerner, rightly contradicting it and trying to setting it aright (see Zerner 1978, p. 213, note 13)]

[in later years Morelli tended also to see an artist’s technique as something containing (and also revealing) characteristic properties (compare for example GM to Jean Paul Richter, 10 June 1886), but remained reluctant to develop his thinking more into this direction, staying probably aware that his knowledge as to artist techniques was not as vast (and also more second hand acquired) than the knowledge resulting from his own long-term observing of artist’s leaving an individual imprint on representational form; and if his attention, in later years, shifted more to painterly techniques, his attention shifted also away from color as belonging also to characteristic properties to work with, for example in terms of a painter’s favourite color (compare Morelli 1891, pp. 72 and 333, for a respective ostentatious self-critique)]

5) Why was Morelli much less inclined to trust and to follow the seeming inherent logic of the Morellian method than were some of his followers?

Morelli jokingly stated to have learned two things

from statesman William Gladstone (whom he met once

at a dinner table, when sitting next to him, probably in 1882 or 1887,

when Morelli visited London): firstly never to go out

without taking an umbrella with him, even if the sun does shine;

and secondly to chew one’s meal at lenght,

before actually swallowing it (see Münz 1898, p. 99).

Both maxims do read, naturally, as expressions

of Morelli’s innate scepticism and therefore cautiousness.

The Morellian approach to connoisseurship did once produce extremely high expectations, and this due to its smelling of simplification, of unequivocalness, of certainty, of objectivity, uniqueness, easyness, and last but not least: it seemed that is was easily and immediately applicable. In a word: apprenticeship time to become a connoisseur in the Morellian sense seemed to be, at least to some, or to some for some time, being rather short.

Morelli, however, who knew of these expectations and hopes, remained rather ambiguous. Which means here that on the one hand and occasionally he seemed to support the view that his approach was able to nurture high hopes, while on the other hand and in his own practice, he remained cautious and sceptical. As sceptical as a connoisseur of art might possibly be at all. And he tended to dull enthusiasm, and even was in the habit to stress that it took a long, long time to learn to see and to become a connoisseur at all, although he also did have Lermolieff state that some Morellian practices were immediatedly or after only a short time applicable, namely the excluding of attributions, based on not-finding characteristic properties (for the stressing of the necessity of patience see Morelli 1890, pp. 13, 15, 18; and for Lermolieff becoming aware of the yet limited, but still off-the-shelf applicability of the just learned see p. 75). And why is that? Why was this ambiguity, this mix of illusion and disillusion possible?

Parrots, according to Morelli 1890, p. 56, do occur often in paintings by Girolamo da Santacroce,

but are they to be considered as a characteristic property? (Morelli does admit a misattribution

on the very same page, having also to do with a parrot in the gallery of Munich…)

We may identify two core notions that played a role in Morellian thinking and Morellian practice, two notions that played a double role, in fueling enthusiasm on the one hand, and in disillusioning on the other. The one notion being the notion of ›characteristic‹; the other notion being the notion of ›distinctive‹.

The problem with the notion of ›characteristic‹ can be seen in its extreme malleableness. It is possible to speak of something as being characteristic, even if we possess only of one example for its being characteristic. For something. If something occurs often, we may also speak of its being characteristic for something, and of course, if something occurs all the time, in relation to something, it is characteristic, very characteristic, for that something too. The more often something occurs in relation to something, we might assume, the more valuable of that something to determine authorship. But the point is that, if something occurs often in one class of objects or even in relation to any object within that particular class, it is not said at all, that this something does not also occur in another class of objects. In other words: what the connoisseur is looking for are preferably, and above all, characteristic properties that belong to one class of objects, to one painters oeuvre exclusively. Only. And if we would speak of characteristic properties only in that sense, we may also replace that term with the notion of distinctive properties. And if such properties indeed would exist, in art as they may exist in nature, in human bodies etc., if one would know them and may have a chance to work with them – this would, naturally, simplify things tremendously. And this was exactly the hope that the Morellian approach did nurture. This was one way, Morelli was indeed understood. Although, one has to say, Morelli did work with all kinds of properties, with characteristics that (in a painter’s oeuvre, as Morelli saw it) occured often (compare M/R, p. 171; referring to Raphael and Perugino), and also with properties that he probably had seen only once or in very few works (like in the case of Giorgione), but still was inclined to regard as being characteristic. Matching a painter’s artistic personality, as he tended to see or to imagine it.

A somewhat hidden reference and metaphorical analogy:

botanical classification according to Carl Linnaeus

The second notion that can be regarded as an offspring of ambiguity is the notion of ›distinctive‹. Because the very notion does imply that, in the world of art, the world of form, distinctiveness does reign. That indeed, if one type of property does occur only in one class of objects and can be regarded as being a distinctive property, this distinctiveness is, as it were, guaranteed. And not disturbed by fuzziness, able to undermine the clear distinction between single artists, artist’s schools etc. The Morellian approach tended to suggest that it might be possible to tell a painter from another, by differenciating clearly distinctive properties that belonged to one class of objects respectively, but failed to show comprehensibly and verifiably that the world of form was indeed ruled by distinctiveness and not by fuzziness. And failed to say, to what degree fuzziness was also acceptable, and failed to say what the connoisseur was supposed to do, if the world of form did not seemed to be like the Morellian thinking theorized (and wanted) it to be. A thinking that had suggested, at least to some, that uniqueness was to be found, uniqueness, like for example in botany was to be found, uniqueness that one could, apparently also rely on, since a tree, a plant, did produce leafs and fruits with some regularity to rely on.

While it remained unclear to what degree the world of art actually could be seen in analogy to botany (compare, for the analogy, for example Jean Paul Richter 1883, p. 3; and compare also Wölfflin 1968, p. 7, with note 1). Did the single painter behave like a tree, producing leafs and fruits, that is, characteristic properties, with a similar regularity to rely on? That one could build on the observation of such regularities in determing authorship? Relying on the Morellian approach like a botanist might be inclined to rely on a classificatory system to determine the identity of a plant?

And if so: why did Morelli allow exceptions, for example by saying that only ›almost every painter‹ showed ›habits of the hand‹ (Morelli 1890, p. 94)?

Given all that, given several sources of equivocalness within the Morellian thinking and inherent to the practice, it is little surprising that, given also the high hopes nurtured by the very approach, various connoisseurs and art historians responded very differently to it. Some with being rather overwhelmed by the vision to conceptualize the study of art in analogy to botany. Others scared by the very vision, fearing that other interests, other methods also, and a more intuitive approach very in particular, would be outshadowed in the near future.

And in the middle of all that, of hopes and fears, remained Morelli himself. Rather remaining ambiguous, not knowing exactly (as we may assume) to what degree high hopes were actually justified.

Still, if Morelli was in the habit of saying that to become a connoisseur long apprenticeship was necessary, he was probably very serious with it (although he did like also to dull the enthusiasm of proud young man that he sensed would not respect him as a master), because if one thing he had learned proceeding rather slowly in comparing works of art with scrutiny (a practice also slowed down, since travelling remained necessary), it was probably that every single case was different, requiring the connoisseur to make long series of comparisons, infinite series actually, since one could never be sure at all to have found all the necessary to determine authorship with certainty, a Morellian apprenticeship, all in all, not resulting with a readily applicable method that indeed could serve as a simplification (and if there had been such, Morelli would probably not have liked young people using it to outshadow himself, who had acquired his skills only in long practice over the years).

Morelli tended, according to his sceptical nature, to stress the relativeness of certainties, the relativity also of any methodological concept. Since there were many different situations, many different problems that a connoisseur could face. And certainly there was not the single one golden rule, to get rid of any unequivocalness, of any situation that confronted the connoisseur with a problem the Morellian thinking had not yet prepared him for.

Does the peacock point to Pisanello or to the school of Stefano da Zevio?

(compare Morelli 1893, p. 103)

Morelli’s attributions, in sum, did rest on systems of comparisons, on constructions built on ›if and then‹, like any other connoisseurs attributions were. If the working with Morellian properties seemed to simplify things, it was also due to a general ignoring that the general impression in front of an individual work of art remained important as a reference (as the something that had to be checked by Morellian controls). And even if it might have seemed to some that a vast knowledge as to artistic personalities was not longer required, since the working with distinctive properties could replace a long apprenticeship, necessary to really get to know the artists and their respective personalities, this was due to an easily turning of the Morellian thinking into Morellian ideology.

With Morelli, to some degree, fueling such tendencies, but, all in all, remaining, sceptical and rather ambiguous. While two of his actual pupils or heirs, namely Jean Paul Richter and Bernard Berenson, went, in their collaborating, but also individually, through a phase of high hopes, associated with the Morellian approach (compare Seybold 2014a; and see particularly Kiel (ed.) 1962, pp. 70 [Berenson in 1893], 113, 285 [Berenson in 1949]). Both sympathizing and identifying with an extremely positivistic interpretation of it, and each of them leaving also, without any doubt, this initial phase behind, and finally regarding the Morellian approach as something more ambiguous that initially it may have seemed to be.

But neither of them – this phenomena also might be seen as being significant, tragically significant – did ever acknowledge the experience of having worked, guided by Morelli directly or indirectly, over many years, if not over many decades. None of them reflected about respective illusions and disillusions concretely and publicly. In other words: no one felt responsible for a critique of ideology that also had been part of the Morellian phenomena. That had been, speaking psychologically here, an amalgam of high hopes and bitter disappointments, all associated with a central figure, who had known of his ambivalent reception very well, and had chosen rather to observe what others made of his approach, than to comment on any phenomena of reception. Remaining rather secretive as also was Morelli’s habit. And here probably due to his sensing that there was no way to better direct or to redirect such a complex phenomena as the response to his envisioning of scientific connoisseurship was. And probably also due to a not being very certain in the end, in relation to what degree one actually could, with or without reserve, rely on the approach associated with his own name.

To find out, respectively to test empirically the validity of the Morellian method, remained to posterity. Who chose to ignore the problem and the leave the whole approach, including high hopes and disillusionings of all kinds, behind and to proceed rather like one had proceeded before: combining intuitive and more rationally reflected practices ad hoc, without sticking to a rigid methodology nor to a classificatory system, nor to procedural standards of science or a culture of verifiability or falsifiability in general. Dismissing the vision, without a differenciating between justified hopes and relative usefulness on the one hand, and unjustified ideological language, guiding questionable practices, on the other. And dismissing also the chance to learn from history in terms of a learning from both.

6) Did Giovanni Morelli ›invent‹ the Morellian method (or even ›modern connoisseurship‹)?

Morelli did, occasionally, speak of his predecessors. But if he – at least indirectly – speaks of these authors that also might have influenced him, and of which he even – horribile dictu – might have borrowed some original ideas, that, later, were rather being considered as his ideas, we have to keep aware that he did not acknowledge his predecessors as one would expect a today scholar to acknowledge influential authors and sources. This has not only to do with Morelli’s pride, his (rather secretive) eclecticism, his essayism, but also with his prejudices and deep dislikes.

Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774)

Luigi Lanzi (1732-1810)

»It was customary with the ancient artists to elaborate

no portion of the head more diligently than the ears. The beauty,

the execution of them is the surest sign by which to discriminate

the antique from additions and restorations…« (quoted after

Spector 1969, p. 70: Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768)

Carl Friedrich von Rumohr (1785-1843) as painted by Friedrich Carl Gröger

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND THE CONNOISSEURIAL TRADITION I: ANTECEDENTS

I. MORELLI AND 18TH CENTURY CONNOISSEURIAL TRADITION

If Morelli repeatedly mentioned Pierre-Jean Mariette, namely as ›certainly one of the greater, if not the greatest connoisseur of drawings and etchings in France‹ (Morelli 1890, p. 190, note 2, p. 412; compare also M/R, p. 315), he remained rather silent as to Luigi Lanzi, of whom he directly borrowed or adapted ideas, but accepted in the end that Lanzi could be seen as one of his antecendents (see Morelli 1890, p. VIII, with the naming of »Pater Lanzi«; see Pfisterer 2007, p. 98 for a crucial passage in Lanzi).

But Lanzi was a (former) Jesuit, and Morelli most deeply hated the Jesuits and all that they (the ›Jesuitenpack‹, as he called them also; see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 11 March 1885) did represent (for him). The duty to acknowledge influences properly here, obviously, collided with Morelli’s prejudice as to the Jesuits (which, ironically, has Morelli, to some degree, appear being a ›Jesuit‹, as he himself understood the term).

One has also to take note of Morelli’s very early mentioning of Jonathan Richardson in his early satirical writing Balvi magnus of 1836 (see Morelli 1836, p. 3, and compare Anderson 1991b, p. 37; possibly Morelli has just grasped the name due to an early reading of Winckelmann; for Winckelmann compare Spector 1969, p. 70, since the checking of ear shapes is foreshadowed in Winckelmann, if applied here to ancient sculpture). But most of all one has to mention the possibly most important source as to Morelli’s theoretical thinking: the Raccolta di lettere sulla pittura, scultura ed architettura: Scritte da’più celebri personaggi dei secoli 15, 16 e 17 by Giovanni Gaetano Bottari (in the edition of 1822, the first edition having been published in 1754-1768).

Enrico Castelnuovo had been the first to point to this work as a possible inspirational source for Morelli and the Morellian method (see Castelnuovo 1968), and namely to one letter from this collection (Luigi Crespi to Giovanni Gaetano Bottari, 25 September 1751; from Bologna). But one has to add also, and this as a supplement to Castelnuovo, that Morelli indeed and explicitly (if in another matter) referred to the very volume of this collection that contains this particular letter (see Bottari 1822, vol. 4, pp. 382-385, particularly p. 383; and compare Morelli 1891, p. 182, referring to p. 368 of Bottari 1822, vol. 4, with Morelli also naming Luigi Crespi).

And if it seems plausible (due to this referring to the same volume and to both names) that Morelli was probably, at least at the end of his life, aware of his predecessors and that he probably and also had taken some inspiration from them earlier or even borrowed key ideas from them, it also seems plausible and fair to say that he missed or failed to acknowledge this influence properly and during his lifetime.

It is not about to prove such an influence here (which, lack of sources, cannot be proved anyway, but just made plausible), but to put Morelli into context of a larger tradition of connoisseurial thinking. And not the least it is about stating, since we are observing Morelli working with Bottari 1822, that Morelli most likely knew much more of his predecessors’ ideas than he did like to acknowledge, and that due to a probable secretly borrowing and adapting key ideas, he generally appeared – at least to his contemporaries – more original that he probably was, with Bottari/Crespi being – then and today – rather being read only by specialists.

This however, does not change much as to Morelli’s role in history (it is rather about nuances), because ideas of his predecessors had probably not become that influential, if they had not become influential through Morelli, adapting them and synthesizing them (with other influences) as a brand, commonly known as the ›Morellian method‹ (and this was what Morelli, explicitly was admitting/pointing out in Morelli 1890, p. VIII). His role, thus and as for today, appears to be more that of a mediator, eclectic synthesizer and above all: as the quintessential representative of a quintessentially rational approach to connoisseurship, and less or not only as that of an innovator or inventor, creating, seemingly, out of nothing, and this due to a tradition being little known or, as one has to recall again in this context, all too little made known by a particular follower of this tradition.

II. MORELLI AND EARLY 19TH CENTURY CONNOISSEURIAL TRADITION

Morelli’s strength was not originality but his all-sided receptiveness. Because the Morellian method was nothing but a composit, a synthesis. If four man, four antecedents would have had cooperated – they could have come up with this particular synthesis as well. And a synthesis can still be called an invention or an innovation, as long as one does stay aware that that particular invention can also be called a synthesis.

Carl Friedrich von Rumohr has to be named here. He was, as to art, also a mentor of the Frizzoni brothers, Morelli’s friends. And since Morelli was engaged in affectionate rivalry with the Frizzoni brothers, Morelli would never have stressed that he did also did read books by Rumohr, and that he also did learn from Rumohr all too much. The ›Morellian imperative‹, as one may call it, does apply here very well: do learn – as secretive as possible – from those that you also – as ostentatiously as possible – do criticize. And Morelli did discuss/wrangle with Rumohr in his books (see Morelli 1880, pp. 290, 293, 300 etc.; Morelli 1893, pp. 150, 153, 157 etc.), but he did also learn from Rumohr and find inspiration in Rumohr.

What particularly did Morelli learn? Among other things (he probably took his notion of ›Angewöhnung‹ (›habit‹) from Rumohr) he learned – and he even did hear Rumohr demonstrating it in person – that making attributions was about giving reasons for attributions, or at least to explain attributions by giving reasons (see GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 24 April 1839; compare also Agosti/Manca/Panzeri (eds.) 1993, vol. 1, p. 368 (Gabriele Bickendorf)). In a word: Rumohr did represent the scientific stance as such (as also Waagen did), and Rumohr, in a more broad sense, did also represent German art historical culture that was already on a path of rationalization and modernization (in parallel to the German school of historiography), primarily as historical critique of tradition, a culture of Quellenkritik was concerned (and as, for example, the reliability of Vasari was concerned).

And if Rumohr was one of the four fathers of the Morellian method (or one of four influences that added up to ›one Morelli‹), philosopher Friedrich Schelling was another, who delivered the theoretical backdrop of the Morellian method, the view that artists bewusst-bewusslos externalized their mind in producing works of art and imposed their inner notions of form, being part of their mind, upon form.

The other two fathers we have already named: Luigi Lanzi who did also recommend the shifting of one’s attention to marginal properties, and also in Bottari Morelli might have found a similar idea. Last but not least one might again mention Winckelmann, who recommended the checking of ear shapes as to ancient sculpture.

To this four (or five) main influences that added up in the Morellian method, several other factors might also have been important in shaping Morelli’s thinking: physiognomy, particularly as to his early years (compare for example his description of poet Friedrich Rückert in chapter Visual Apprenticeship I, as well as his discussion of Genelli’s head of Don Quixote, given in chapter Visual Apprenticeship II), his being a sitter for various Munich artists, an experience that might have made him realize how these artists imposed their notions of form upon the representation of his body; and also and particularly his dialogue with Genelli and with the Frizzoni brothers, that, as we have shown in the introductory essay, led Morelli to think about the being important or not being important of small defects in drawing.

It was also Genelli, by the way, who directed Morelli, in 1841, towards the theory of ›automimesis‹ (see note below).

Last but not least: unlike Morelli was to suggest later – many connoisseurs were also working with distinct properties and also more or less rationally (and were not exclusively, as Morelli suggested repeatedly, relying on a general impression only): Rumohr had for example stressed the unique drapery in Giotto (Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 159), but if we would go farther back and would review tradition, we would also find more and more writers, attempting to conceptualize a working with distinct properties. And as a contemporary of Morelli we would find Adolph Bayersdorfer (compare chapter Visual Apprenticeship II and III) and Ludwig Scheibler (whom his teacher Carl Justi also explicitly did compare with Morelli; see Carl Justi to Jean Paul Richter, 26 December 1889, Bibliotheca Hertziana). And when Morelli had heard that one had compared his working, his method, with for example Lanzi, and with even the Goncourt brothers’ making of observations in works of art, he did not even energetically defend himself (see again Morelli 1890, p. VIII; and compare Pica 2004), but stressed what he have said above as well: it needed someone to actually do what he was doing, even if others had had similar ideas (like for example Luigi Lanzi). Morelli had made himself an advocate of scientific connoisseurship (and this nor Rumohr, nor any other connoisseur had done). And if someone did synthesize and conceptualize ideas that also were ideas of others, ideas that this someone did reinterpret in terms of 19th century scientific culture, one may still call this someone an inventor or innovator. Morelli certainly was one, even if he did not invent out of nothing, even if all – all ingredients of the Morellian method that made a synthesis can also be traced back in history to other thinkers. And namely also to some thinkers whom Morelli did not particularly like to give them more credit than actually necessary (and in fact, he gave them less, at least as far as Rumohr and Schelling, but also as far as Bottari was concerned). As to Lanzi he did, at least in some sense, give him credit: in not contradicting the view that ›Pater Lanzi‹ actually was his antecedent (implying that the Morellian method had – also – grown out of the ideas of a member of the Jesuit order).

And an allegory of misleading art historical traditions (compare Morelli 1890, p. 113, note 1):

›How often one is being reminded, if reading books of art, of the parable, having been represented so delightfully by the splendid old Brueghel, in his picture in the Museo of Naples.‹

»Wie oft wird man nicht in Büchern über Kunst an die Parabel erinnert, die der treffliche alte Brueghel auf seinem Bild im Museo von Neapel so köstlich darstellte.«

This version of Herakles und Omphale (or Herkules und Omphale) by Bonaventura Genelli gives an impression of what Giovanni Morelli and his

friend Giovanni Frizzoni did look at in 1846, when quarreling over a rendering of a ›singing Hercules‹, and over ›to look or not to look

at minor defects, when looking at art‹ (compare the introductory essay to the present monograph)

(source: Ebert 1971, p. 45; it is theoretically possible that the here reproduced work was coming from a Frizzoni collection and actually was

the then discussed work, but this can not be ascertained; Genelli, in 1862, painted his better-known painting of the subject;

and as to the subject in general compare Nielsen 2005, pp. 35ff., and again Ebert 1971, pp. 163-165).

[if the theory of ›automimesis‹ (see Zöllner 1992) is to be counted among the intellectual origins of the Morellian method is a question that deserves particular attention: in 1841, in writing that he was complying to 25-year-old Morelli’s wish to have a portrait of Genelli, that is: an autoportrait, Genelli did also say in passing by (Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 30 November 1841):

»Mein Wesen soll leider in allen meinen Figuren liegen, so sehr ich mich auch mühe, es zu verleugnen – ein Fehler, den, wie es scheint, kein Künstler ganz abzustreifen vermag.« (›Unfortunately my nature is said to be in all of my figural characters, as much I am dedicated to deny it – a defect, that, as it does seem to me, no artist is capable of casting off completely.‹)

And in 1874 Morelli was to refer to the theory of ›automimesis‹ as it is to be found in the ›Treatise on Painting‹ by Leonardo da Vinci (Morelli 1874-1876, p. 8; again in Morelli 1890, p. 95; compare again Zöllner 1992, referring, in passing by, also to Morelli); it is not known, however, when Morelli did read Leonardo for the first time (nor do we know what exactly happened in Morelli’s mind in 1841 and afterwards); it may be that, much later, Leonardo was to be, for Morelli, a high-profile voice or the high-profile voice he needed, confirming the general direction of thinking, to be associated rather with Schelling, whom Morelli – this is also particularly noteworthy – just had met, accompanying Gino Capponi to Munich, earlier in 1841; and whose Rede über das Verhältnis der bildenden Künste zur Natur Morelli was going to translate subsequently (Morelli 1845); again: what exactly happened in Morelli’s mind, when clarifying his own thoughts as to connoisseurial method in around 1860, that is: only several years later, and when synthesizing thoughts of others that we have named above, remains unknown; but what we do see here is, as it were and at least, the pre-historic context of the Morellian method in its originating in Morelli’s mind, with Morelli certainly drawing on many inspirations of others, including that of his friends, Genelli and the Frizzoni brothers very in particular]

7) Which was the more ›revolutionary‹ implication of the Morellian approach?

If science, as far as any discipline might be concerned, cannot be thought without a culture of verifiability and falsifiability, scientific connoisseurship cannot be thought without it.

Since a culture of verifiability and falsifiability that actually would deserve that name did never exist in connoisseurship, scientific connoisseurship did only exist as an idea (and this although Morelli is sometimes thought of as having caused an actual revolution, in terms of establishing scientific connoisseurship, and in establishing positivism in the discipline of art history; compare Schlosser 1934).

Which is why we designate the idea of a culture of verifiability and falsifiability (an idea that Morelli himself did not fully live up to) as rather being an implication of his envisioning scientific connoisseurship and a positivistic science of art, and of his demanding of a general giving of reasons for, and explanations of any attribution of a work of art to a respective author, very in particular (compare Morelli 1890, p. 42; Morelli 1891, p. 16: »wie sich dies von selbst versteht«; M/R, p. 75). A revolutionary implication, because the realization of it would have had, if it had occured, changed connoisseurship, equalled here with attributional studies, fundamentally. But this was never the case.

8) Under which historical and biographical conditions Giovanni Morelli did develop his approach?

If it has been said that Morelli ›did invent connoisseurship to save the cultural heritage of Italy‹ (Anderson 1999b, p. 233), one has to say that Morelli himself never did explicitly link these two things, although he was also concerned with Italy, at his day, being a country in development, and with protecting and better caring for its cultural heritage.

In fact Morelli did explicitely link his seeking for a method with his own being rather uncertain as to the determining of authorship of works of art (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 21 May 1885). And in not limiting the context where such uncertainty would have mattered, Morelli leaves us with raising the question what these specific contexts were. And if fact, these were as diverse as connoisseurship, in its applied version, was and is a diverse field of human practice. Plainly speaking: Morelli did make a living, from the later 1850s onward, also with, which means: to some degree, with dealing with works of art, as far this seemed useful, possible, reasonable and not all-too unpatriotic to him. While he was also concerned to help inventorizing and protecting the cultural heritage of his home country. The background of his rethinking connoisseurial methods, thus, was ambiguous. And if one stresses only single aspects of it, one does run in danger to simplifiy that ambiguity. To the better or worse. But it remains also useful to remind that Morelli had its own moral standards, and one can observe him struggling with his own standards and with his own ambiguity. Which means: it is actually not necessary to measure Morelli’s practices with later moral standards (of posterity). All the more since his own moral standards were high and rigid. But this means also that one should not ignore his occasional struggling with his own values either.

9) In what wider programmatical context the Morellian approach to connoisseurship has to be seen?

With renderings of the Madonna by Raphael Morelli did see the Holy Mother

›leaving the church‹, becoming simply mother (see Morelli 1893, p. 253):

given here are renderings of Madonna and Child – from Morelli’s own collection

(source: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

A most ingeniously rendered swan…

…if compared, for example, with Hondecoeter…

…or with Asselijn (see Morelli 1890, p. 194).

Morelli did not only envision scientific connoisseurship, but scientific connoisseurship as being the basis of a science of art (Kunstwissenschaft). This raises the question what Kunstwissenschaft, for Morelli, might have been all about in general. And scattered in his books we find remarks that, for example, art showed man in his passions (»den Menschen in seinen Leidenschaften«; Morelli 1893, p. 140; reffering to Boltraffio who, in his view was lacking this ability), or that, what made a great artist, was, again in his view, an exeptional ›power of invention and a talent for original representation‹ (»Erfindungskraft und originelle Darstellungsgabe«; Morelli 1891, p. 311). His most frequently used adjectives, in describing art that he liked (and he did not, as Aby Warburg did imply (Gombrich 1992, p. 182), admire ›without using adjectives‹), were probably ›aimable‹ (›liebenswürdig‹; see for example Morelli 1893, pp. 93, 191, 212) and ›spirited‹ or ›ingenious‹ (›geistreich‹; see for example Morelli 1890, p. 194; Morelli 1893, p. 252, note 1).

Beyond this personal and more subjective relation that Morelli had and cherished with individual artists and individual works, he was also interested in the evolution of art as such, and also to observe and to understand evolution within the whole vast panorama of a history of art, written and organized upon scientific principles; and this is to be regarded as the more hidden, more implied relevance that scientific connoisseurship, as being the basis of a future Kunstwissenschaft, also might have had for him: only the most solid and rigid classification would one enable to perceive how art developed, in analogy to nature (and maybe also, according to the Naturphilosophie of the romantic era, as creative nature or natura naturans), and, as one must add, in analogy to natural evolution. And any attempt to think the history of art as the result of artists exerting influence on each other, that is according to a ›Beeinflussungstheorie‹, Morelli could only see as an undermining of his, of the evolutionary approach (see for example Morelli 1890, pp. 166, 169, 220, 375; Morelli 1891, p. 165; Morelli 1893, pp. 71, 99, 110, 155, 291).

Beyond that Morelli, if only once and in his typical impulsive way (and while he was probably aware that he was more the man to inspire than to carry out any undertaking demanding a large amount of discipline), he did suggest to his pupil Jean Paul Richter to write a treatise on the history of taste, focussing on the psychological factors working and revealing themselves in appreciation of art (which is: in social history, a field of history, not being equal, but corresponding with a history of artists, artist’s practices and works of art) (see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 11 June 1885).

10) What had Giovanni Morelli in common with Sherlock Holmes? And in what way these two figures do differ?

If one does compare Giovanni Morelli with Sherlock Holmes, the latter thought as a symbolical figure of global imagination, representing the triumph of close observation, the power of deduction and insight into human nature, in sum: representing the triumph of reason, a reason that manages to re-establish order in the world (after order had, by a crime, been disturbed), then Giovanni Morelli and Sherlock Holmes have rather little in common.

We would have to set the relative triumphs of Giovanni Morelli against the overwhelming triumphs of a symbolical figure representing the triumph of reason as such. And as we show in this section, the relative triumphs of Giovanni Morelli can, moreover, not necessarily traced back (in every case and fully) to his full and only applying of reason (compare also answer to question 21).

Nonetheless also Giovanni Morelli is and can be regarded as a symbolical figure, not of global imagination, though, but as a figure representing a quintessentially rational approach to art connoisseurship. His followers might have wished that he represented also the triumph of reason as to this field of human practice, and some traditions indeed tried to create a respective image of Morelli. But Giovanni Morelli, thought as a historical person, can certainly not be interpreted, without any reservation, as representing the triumph of reason in connoisseurship. Moreover: Morelli was far too sceptical to think of himself, in earnest, in such a way, and would have thought a respective claim to be pretentious and ridiculous (even if he did enjoy to some degree, if he was admired and praised; but too much praise, nonetheless, resulted in wild outbursts of scepticism, which did represent, again, one side of his highly sensitive character, but not his character as such).

Museum director Henry Edward Doyle (1827-1892),

whose acquaintance Morelli made in 1887,

was an uncle of Arthur Conan Doyle

(picture: libraryireland.com)

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) in 1890

If one does compare Giovanni Morelli with the Sherlock Holmes of the Sherlock Holmes-stories and -novels, who is a more complex character than his relative, the symbolical figure of global imagination, these two characters, who also inhabited one and the same historical space, one and the same historical epoch, have much more in common. Both disposed of irony, of observational skills, and the power of deduction, and both (we have, as to this matter, also to rely on Dr. Watson) were not able to solve every case they were being confronted with at their day (Dr. Watson explicitely does state, in fact, that he, Watson, did not find those cases, wherein Holmes did fail, worthy of being transmitted (see The Five Orange Pips); and also in art historical traditions we find such manipulative strategies of respective politics of memory, however, less successfull strategies than in the case of Holmes). Last but not least one may add that Morelli was, in tendency, rather Anglophile (compare Münz 1898, p. 98f.; also as to Morelli’s encounter with Gladstone) and had, with some reservations, a generally positive image of English civilization (his English was probably as good that he could read English texts, but he could not speak English as fluently as for example he spoke French).

If one, thirdly, does compare Giovanni Morelli with Sherlock Holmes, the literary character, that is: one human character with another human character, one can hardly ignore that Giovanni Morelli, unlike Holmes, was a man with abundant emotions, emotions that he was (with few exceptions) not entirely capable of hiding or controlling, even if he aimed to do so. His passionate nature showed and that was that.

While Holmes, if he was a more emotional character than he did show (even to Dr. Watson), he must have been capable of controlling his emotions and thus of hiding them, even as to those next to him, from being revealed. Both, by the way, Holmes and Morelli, were living their lives as bachelors.

(Picture: youtube.com; small picture above: theguardian.com)

(Picture: youtube.com; for references to films and actors see here)

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND SHERLOCK HOLMES

1868: Morelli, for 24 days, visits London for the very first time (compare GM to Jean Paul Richter, 25 May 1878 (M/R, p. 60f.); and see Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 187).

1876: Cesare Lombroso, L’uomo delinquente (1887 translated into German).

1878: Morelli recommends to his pupil Jean Paul Richter, not without a trifle of irony, to look at pictures – and to interrogate pictures – like a former police inspector (»Inzwischen aber fahren Sie fort viel zu sehen, aber jedes Bild vorerst mit den Augen eines vormaligen Polizei-Kommissärs sich anzusehen und auszufragen.«) (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 22 April 1878 (M/R, p. 54; compare also p. 57)).

1882 (June): Morelli visits London for the second time.

1886: Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab is a world-wide bestseller, even outselling Arthur Conan Doyle.

1887: in February Carl von Lützow includes an ironical note in his Kunstchronik (the supplement to the Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst), according to which the Berlin police has adapted the Morellian method (see [r.] 1887); in the summer Morelli visits London for the third and last time; he is also presented to Queen Victoria (see chapter Visual Apprenticeship III), and he makes the acquaintance of Henry Edward Doyle, Director of the National Gallery of Ireland, who is also an uncle of Arthur Conan Doyle (see Carlo Ginzburg 1979b, p. 64, note 10); Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet.

1890: Arthur Conan Doyle, The Sign of Four; Alphonse Bertillon, La Photographie judiciaire.

1891: Morelli dies at Milan (28 February). – According to his ficticious biography (compare timeline in Doyle 2005-2006, vol. 3, p. 859), and according to Italian sherlockiano Enrico Solito), Sherlock Holmes, after his seeming death in Switzerland, gets to Florence in May (and this via Milan).

1892: Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes; Carlo Placci, Un furto; 1892/93: Arthur Conan Doyle, The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes.

1897: Cesare Lombroso contributes an article on the Belgian artist Antoine Wiertz to the journal Emporium to which also Gustavo Frizzoni does contribute.

1901/02: Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles, wherein Sherlock Holmes poses ironically as a connoisseur of art (and relies on portrait likeness in his looking at art and not on Morellian detail, that is: not at anatomical notions, possibly imposed by a painter upon the representation of a real person, and also, according to Morelli, realized if a painter might have been indeed obliged to portrait likeness in his rendering of a real person); various other Holmes-stories show the detective seemingly working as Morelli did (see Zöllner 2009, p. 57, referring to Ginzburg and to the Holmes-story The Adventure of the Cardboard Box of 1893), when in fact Holmes’ working with clues is operating on a comparable (since it is also about likenesses of ears and about identification), but different level (since it is about real family likenesses and about identifying individual persons as relatives, thus about likenesses not guaranteed by artist’s deliberate-unvoluntary habits – as far as the Morellian theory does stand –, but by nature, or: by biology and its laws; the distinction being important since not making this distinction might result with implying that alleged artists’ habits might be as reliable to make formal comparisons, as are or might be laws of nature).

1902: at the London Lyceum Theatre Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter with his family sees the performance of a Sherlock Holmes play (see diary of Jean Paul Richter, 9 January 1902; and compare Doyle 2005-2006, vol. 3, p. 241: play by William Gillette/Arthur Conan Doyle).

1903/04 (September 1903-April 1904): Bernhard and Mary Berenson travel to the United States to promote the ›new science of connoisseurship‹, which, according to Mary Berenson (as she says for example in a lecture given at the Pennsylvania Museum on February 2, 1904), is to be compared with the detective work of Sherlock Holmes (David Alan Brown 1979, p. 18).

1913: Hans Tietze associates Morelli with Bertillon (compare Vakkari 2001, p. 49).

1927: The American Magazine of Art refers to Bernard Berenson as a ›Sherlock Holmes of the world of art‹.

(Picture: polizeimuseum-stuttgart.de)

Questions and Answers

(Source of small picture above: Honegger 1997, p. 91 (detail))

B) THEORY AND PRACTICE

11) Is the application of the Morellian method limited to, for example, Italian Renaissance art?

Jackson Pollock scholar Francis V. O’Connor can be named

as one modern connoisseur, dedicated to abstract painting

who did refer to Giovanni Morelli in his writings

(see O’Connor 2012ff.)

To think about an application of the Morellian method in its narrow sense makes sense under the following general assumptions:

a) the art work in discussion does comprise a realistic component or dimension that leaves room

b) for an artist to leave an individual stylistic imprint on this representational dimension (like for example on the morphology of human anatomy) beyond the more obvious stylistic paradigm an artist is working in (the work of art, thus, does in a sense allow to shift one’s attention to marginal detail, where individuality might – might – reveal more distinctively than it might reveal in the main features, regarded as being part of the more obvious stylistic paradigm an artist is committed to);

c) the existence of characteristic stylistic regularities can also empirically be shown and verified, in its being characteristic (for a particular artistic personality), and in its being clearly distinguishable in relation to other artist’s personalities (and stylistic properties); in other words: the method is applicable if fuzziness and lack of distinctiveness do not undermine its reasonably being applied (corresponding to the also necessary acknowledging of any general impression, as regards the artistic personality revealed in a work at hand).