M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Study

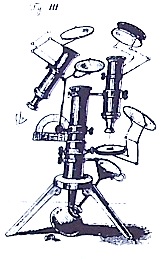

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY Cabinet V: The Future of Morellian Connoisseurship or: Digital Lermolieff  (Source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 252) |

Giovanni Morelli used to refer to the kind of Kunstwissenschaft he imagined as to a new building. The architectural metaphor makes visible what he imagined: something that had to be build, something that stood there solidly in the end, but first had to be built (and it was not yet there). And this implied a process. Over time.

Auguste Compte (1798-1857)

Herbert Spencer (1820-1903)

In how far and in how exactly Giovanni Morelli was a man of his time? Of the 19th century, the age of progress? We have to study how Giovanni Morelli spoke of time. And progress. And the studying of the metaphors, of the language he used show exactly the, broadly speaking, two sides of his nature: his optimistic and his sceptical one.

ONE) A CONTEMPORARY OF JULES VERNE OR: GIOVANNI MORELLI AND THE FUTURE

CABINET V: THE FUTURE

OF MORELLIAN CONNOISSEURSHIP OR:

DIGITAL LERMOLIEFF

(ONE) A CONTEMPORARY OF JULES VERNE OR:

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND THE FUTURE

(TWO) DIGITAL LERMOLIEFF![]()

›Here we see the build of men, that is, of painter and of pen‹

(Illustration by Ernst Fröhlich; compare also

Anderson 1991b, p. 34)

(Pictures: google.books.com)

It is worth mentioning and recalling that the first satirical piece of Giovanni Morelli, his Balvi magnus of 1836 (Morelli 1836), had been based, among other things, on the basic thought that, whatever science might be saying, that it possibly might turn out to be pure nonsense what science was saying.

Because on one level this piece had shown science, very eruditely, interpreting a work of art, while on another level, the satirical piece had deconstructed this erudite explaining to being nothing but pure nonsense. Since the work of art in question showed, on yet another level, the members of the lunch club of young student Giovanni Morelli at Munich.

This construction implied, on the one hand, that absurd meaning could be attributed to any work of art, and by whomever. And on the other hand that science could be terribly wrong (but also to amusing effect).

While on yet another level, it showed that reality could be, the word may be allowed here: romaticized (or poetically manipulated): the picture of a Munich student lunch club on a vessel, that future generations of archeologists were one day to dig out, to finally interpret the picture. Completely wrong, as it may turn out, but in again romanticizing the already charming reality of a lunch club of Munich students, and making something else, something even more charming, more imaginative, more dignified even or something absurdly comical out of it (like Morelli had, in his piece, on his part, and to the amusement of the members of his lunch club and to the amusement of others), made something imaginative out of his beloved lunch club. The Balvi magnus, possibly, being a most amusing, but also a highly philosophical satirical piece. Probably Morelli’s most philosophical piece, in terms of thinking about the science of art history, by means and in terms of satirical literature. And this as early as in 1836. And, in some sense, satirizing Iconography and Iconology.

This all is worth being recalled here because Morelli’s scepticism as to all too stiff and self-opinionated representatives of science never did change much all through his life. He had chosen dignified representatives of science in his early satirical piece to be ridiculed, he later had enjoyed to read how Alessandro Manzoni had given a portrayal of all too serious science in his I promessi sposi (epitomized in the portrait of Don Ferrante; compare GM to Jean Paul Richter, 13 January 1885, for a referring to Don Ferrante), and in his later years, he also casted living representatives of science, namely and preferedly German professors and connoisseurs, for these roles. To demonstrate that, whatever science may be saying – it could possibly turn out to be pure nonsense (and of course it could also be of use to just pretend this, to a mere strategic benefit).

This all has to be taken into consideration, if it is thought about Morelli and scientific connoisseurship, and specifically about renewing, possibly renewing, connoisseurship or scientific connoisseurship in a Morellian spirit. In a word (and put rather mildly): science as such, as seen by Morelli, was never something to be seen as absolute. Rather on the contrary. But not absolutely on the contrary either. It was not about not being earnest at all. But about being earnest, as earnest as one could reasonably be. And to find out about how earnest, about to what degree one could reasonably be earnest, the aid of satire might also do well as a very able finding aid.

And since Morelli saw scientific connoisseurship, in a sense, as being science fiction at his day, because scientific connoisseurship had not yet been realized on earth and yet had to be established in the future, we have to keep in mind how Morelli thought about science in general, if we are reviewing how connoisseurship has developed in the meantime, and think about how connoisseurship might develop in the future. Again as science fiction, but not only as fictional science. Into something Morelli had envisioned, or into something completely else.

Only one thing is clear: if this is to be done in a Morellian spirit, we have to keep in mind that it is, at any given moment in time, also about thinking to what degree one may or might be reasonably be earnest. And about if and when it might rather be fit to satirize reality. To ridicule expressions of scientific culture, that are more serious than one might reasonably be. At a certain moment in time. Be it in the present, or the future. And this all applies, if we are now going to think about scientific connoisseurship at the age of digitization, and if we are going to think about the vision of Digital Lermolieff.

Giovanni Morelli on Time, Future and the Progress of Science

1873: Giovanni Morelli visits the World Exhibition at Vienna (see Agosti 1985, pp. 57f.); in 1872 he had travelled to Spain and during the 1880s (see Münz 1898, p. 88) he was to state that ›after having seen Spain‹ he had becoming aware of the progress – speaking very generally – Italy had made (in comparism with Spain and in its general developing as a country).

1874: With enthusiastic agreement Giovanni Morelli reads an article by French critic and theologian Joseph Antoine Milsand, entitled L’Angleterre et les nouveaux courans de la vie anglaise in the Revue des deux Mondes (compare Agosti 1985, p. 61); the article also deals with various manifestations of positivism and with the risks of an absolutism of scientific reason.

1879: Donna Laura Minghetti, not being inclined to share the opinions of her ›positivistic friends‹, is concerned with the ideas of Herbert Spencer, whom she and her husband Marco Minghetti (both friends of Morelli) also have met; she asks Lord Acton for his opinion, who passes the question to Belgian economist Émile de Laveleye (Laveleye 1880, p. 356ff.).

1880: »Ich halte es mit dem Grundsatze, dass der Zweifel der Grund aller Erkenntnis ist.«

(Morelli 1880, p. VIIf. [the preface being dated as by 20 July 1877])

1880: »[…] um mit der Zeit aus dem leidigen Kunstdilettantismus heraus zu einer Kunstwissenschaft zu gelangen […].«

(Morelli 1880, p. X)

1883: Morelli repeatedly utters the opinion that his method is ›of help‹ to attain sound results in 80 cases out of 100 (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 17 July 1883; GM to Austen Henry Layard, 14 July 1883 (Anderson 1991a, p. 569); this is not to be interpreted as saying that the error margin of the method would be 20 percent (as Anderson has it, and even if Morelli meant to suggest just that), since the method is not to be considered to be complete in itself; as a mere aid (which is: next to other factors like the intuitive assessment, to be controlled by the application of the method), it cannot be credited for 80 percent of sound results either, since also it is only ›of help‹ and not solely responsible for any result; the number, in fact, might rather be interpreted as referring to a general estimation of usefulness, and what Morelli seems to be implying is actually that in every case the method can actually be applied (be it that this is only the case in 80 cases out of 100), it is also of good help (which is: without any error margin, introduced by the application of the method), since he is not explicitly stating that in all 100 cases the method had been applied; but the statement remains ambiguous and, in spite of its seeming numeric precision, does actually state rather little (except that it is expressing suggestive ambiguity); last but not least one had to ask, who would be deciding whose determination of authorship we would have to consider as being the correct one (and here it seems, most questionably, that it seems to be the one who actually does apply the method that he also does recommend to be applied, while watching over the method’s allegedly being empirically tested, although this is, for reasons of logic, simply impossible, since, again and as Richard Wollheim had it (Wollheim 1974), the Morellian method is not a method complete in itself).

1883: »Jeden Tag überzeuge ich mich mehr, dass unsere Experimentalmethode das beste Hilfsmittel sein dürfte, um mit der Zeit zu einer positiven Kunstwissenschaft zu gelangen.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 23 December 1883 (M/R, p. 298))

1884: »Die Erscheinung der Cholera hat uns diesmal einen wahrhaft schreckhaften Blick in die sog. Zivilisation der europäischen Völker, wenigstens jener latinischer Rasse, tun lassen. Statt Fortschritte sehe ich hier nur Rückschritte. Überall siegt die Macht der Unwissenheit über das Recht der Intelligenz.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 8 September 1884; from Milan)

1887: »Was mir natürlich jetzt am Herzen liegen muss, ist Ihre Monografie der Veroneser Kunstschule. Ich lege ein grosses Gewicht auf diese Arbeit, da ich vollkommen überzeugt bin, dass Sie damit den Grundstein legen werden zu einem Neubau der Kunstwissenschaft, die wir beide im Sinne haben.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 2 January 1887)

1887: »Was die Galerien von Dresden und Berlin anbelangt, so scheint mir (und ebenso München) »im Interesse des Fortschritts der Wissenschaft« beinahe eine Notwendigkeit vorzuliegen, dass Sie auf die neuen Kataloge dort eingehen.«

(Jean Paul Richter to GM, 26 September 1888)

1888: ›Vanitas vanitas totum vanitas. Two years after my death no one in the whole world will even know anymore that I had existed. The little I have produced isn’t worth to be talked about seriously, and all this I am telling you with all seriousness of my soul and my mind. If I have been concerned with ancient art, and this with a patience and persistence worthy of approbation, this is because it has given me personally a great deal of pleasure – but that my intellectual diversion will provide a great service to the so-called truth – this thought did never cross my mind! What do we know, poor creatures, of the absolute truth? Few things, actually, since the knowledge that we manage to attain down here is only fragmentary and yet very imperfect. Thus we have no reason at all to pride ourselves on it. Amen!‹

(GM to Austen Henry Layard, 9 June 1888 (Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 285ff., quote: p. 286f.); my translation from the French)

1890: »Zwar gebe ich gern zu, dass der Begriff, den wir uns durch gute Abbildungen und Darstellungen von der Kunst der Aegypter, der Hindus, der Assyrer, der Chaldäer, der Phönizier, der Perser u.s.f., sowie der Anfänge der griechisches Kunst verschaffen können, nicht blos förderlich für unsere allgemeine Bildung sei, sondern ich bin auch Überzeugt, dass dergleichen Studien den Kunstsinn in uns schärfen und erweitern, vorausgesetzt natürlich, dass wir einen solchen haben.«

(Morelli 1890, p. 21f.)

1890: »Ich behaupte daher, und könnte es Ihnen durch hunderte von Beispielen bekräftigen, dass, solange die Bestimmung von Kunstwerken lediglich dem Totaleindruck anheimgestellt bleibt, ohne die Controle einer aus Beobachtung und Erfahrung gewonnenen Kenntniss der jedem Meister eigenthümlichen Formen, wir fortfahren werden mit Unsicherheit uns zu bewegen, und dass folglich die Kunsthistorie wie zuvor auf wankendem Boden stehen wird.«

(Morelli 1890, p. 24)

1890: »In der Zuversicht nun, mich für immer zu entwaff[n]en und für die Zukunft unschädlich zu machen, beruft sich der berliner Kunstgelehrte auf das Urtheil meines verstorbenen Freundes Otto Mündler […].«

(Morelli 1890, p. 245, note 1 beginning on p. 242)

1891: Morelli utters the opinion that three thirds of his determinations of authorship in the Dresden Kupferstichkabinett will stand the test of time (Morelli 1891, p. 379); on the other hand he states that if his method seemed to be of some usefulness, that this also could possibly be an illusion (Morelli 1891, p. 5f.).

**

TWO) DIGITAL LERMOLIEFF

Referring to a computer one has used the notion of ›connoisseur of art‹ for the very first time in 2004 ([gsz.] 2004), referring to machines carrying out routines of the like, machines are better to carry out than men. For the moment it is not yet about machines acting on their own as connoisseurs of art, but about machines, being guided by human beings, carrying out things that by using a machine can be carried out better than without using a machine and by human beings alone, and we would like to discuss a general management, a visual management, of things visual, but not only of things visual, first here; proceeding to a discussing of specific connoisseurial routines carried out with the help of machines, to finally a discussing of the mere presence of our machines – that by their sheer presence force us to think about more precisely what one would do if certain routines, one day, could be carried out with the help of a machine, even if these things never are to be carried out by machines alone (but only by way of interacting of human beings with a machine, which actually might by stunning enough).

And the sheer presence and principal availability of machines has us also, and finally, rethink what exactly we are doing, if applying the Morellian method. What exactly, and not for example: what more or less we are doing. Because if a machine once was to carry out routines, specifically designed after the Morellian method, this could only be done, if fuzzy logic in our acting (without a machine being present at all) would be eliminated, and if we would, one day, be able to precisely tell a machine or a software application (we would be calling Digital Lermolieff) what to do. What, for the moment, but only for the moment, due to a high degree of confusion as to the exact routines comprised by the analogue application of the Morellian method, would (still) present us with difficulties.

The latter might be a Jules Vernian vision, and also the referring to a computer as a connoisseur of art might still have a burlesque element in it, but certainly our present-day technologies are advanced well enough to have computers (what our machines yet are doing anyway) help us in our administration of connoisseurial procedures, resulting also in more transparence in connoisseurship, a higher degree of comprehensibleness and verifiability, in sum: in an advanced culture of verifiability in connoisseurship, compared with the culture at the day of Morelli, because things are done in a more graphical way, arguments are brought forward in a more graphic way, and also: the empirical validity of formal comparison, of the working with formal analogies – and this, in its core, is what connoisseurship, as we understand the term here, is all about – cannot only, by using methods of visual management, be more graphically be shown, but also more rigidly be tested.

And this, using Raphael as our test case, we are now prepared to do, to test something that, apparently, has never been tested before: to test the Morellian telling us about a Raphaelesque type of ear for an actual and empirically being there of such a type. Thus, we are testing empirically no less than the alleged existence of such a type; and by doing this we are testing, whether the speaking of such a type can be named a solid making a case for the existence of such a type, based on solid empirical arguments, brought forward no longer by mere suggestive words, but by using words and images, as both can be combined in our every day technologies.

MODERN CONNOISSEURSHIP AND VISUAL MANAGEMENT (AND RAFFAELLO SANZIO AS A TEST CASE)

Morelli revealing – in Morelli 1893, p. 318 – as much (or as little) about his view of the Raphaelesque type of ear as he wants to reveal

(but is it also enough to verify his claim, and can the existence of such type of ear indeed be assumed, and if yes, does it also matter, and if not, why not?)

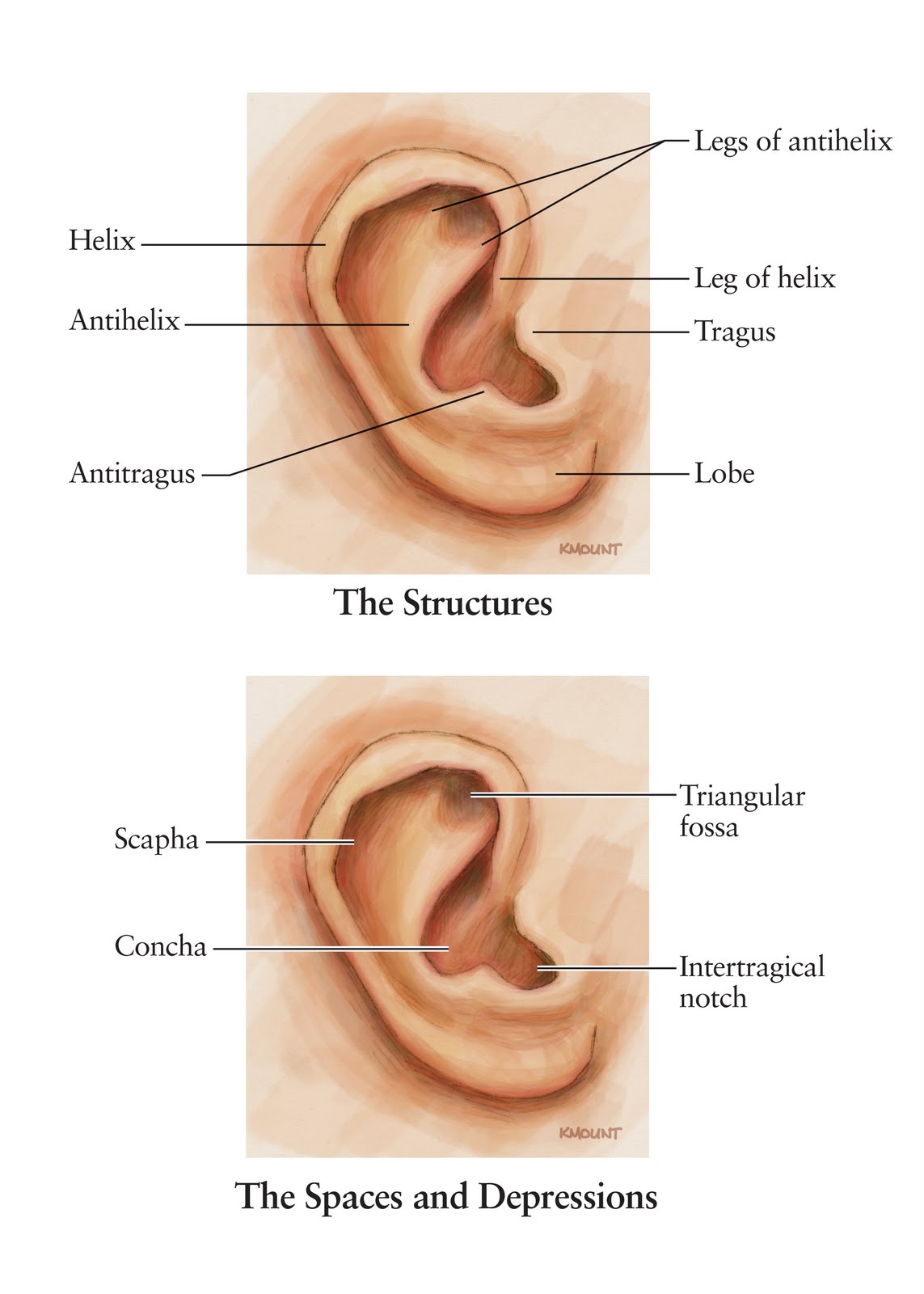

Specialized terminology might help us to see at all, what it is all about

(and this might not be limited at all to anatomical specialized terminology,

but bear on all specialized terminologies, for example of botany, architecture, geology etc.

as far as such terminologies help to designate form of any kind at all,

with ›designating‹ meaning here also and very in particular: helping us, and others, to see)

(picture: anatomyproartifex.blogspot.ch)

A secret hero of The Giovanni Morelli Monograph – the Raphaelesque type of ear

(visualization: DS; sources: Wikipedia and, as to the image in the middle, Morelli 1893, p. 319

(only detail being used here); this visualization draws upon the two examples named by Morelli that,

according to his view, do show the Raphaelesque type even in portrait (Morelli 1890, p. 99f., note 1)

and the one example in drawing that he chose to illustrate his views; see Morelli 1893, p. 319,

and p. 320, note 1, beginning on p. 318; compare also Morelli 1890, p. 60, for a reference to

(and an all too short definition of) the Raphaelesque ear, as well as p. 419)

IN SEARCH FOR THE RAPHAELESQUE TYPE OF EAR: A PERSONAL VIEW

(ONE) DO WE SEE WHAT MORELLI MEANT AT ALL?

The Raphaelesque type of ear is in front of our eyes. But is it to be compared with a purloined letter, nobody seems to be seeing, in spite of its being in front of our eyes? – Not exactly, because things are more complicated here. The speaking of a Raphaelesque type of ear might be in front of our eyes, because Morelli, in his methodological causerie named Princip und Methode and in other places, does speak of a Raphaelesque ear. Art historical tradition seems to know it (at least the speaking of it). But does the Raphaelesque type of ear in fact exist? Because no art historian seems to ever have wanted to check empirically (and publicly) if such type of ear indeed does exist at all (or could someone answer right away the question how the Raphaelesque ear, which means, the Raphaelesque type of ear, in fact does look like? – no illustration, that might be taken from Morelli’s books for whatever purpose is actually available, because there never was, in spite there was a pointing to examples and a naming of examples that show the type of ear – there never was an actual demonstrating of how this type of ear exatly does look like, and an example representing a type might not be enough to illustrate the type itself, and is not to be confused with a basic type of shape as Morelli did understand it).

And this being now and here in search for a Raphaelesque type of ear might be due to no art historian ever have been interested to check empirically if Morelli’s claims were plausible at all (because we would have had the chance to point to earlier discussions); or due to no tools being available to conveniently check it; or due to everybody’s knowing that such type did not exist at all; or to everyone’s preferring to better not touch the question at all (because, for example, there is everlasting confusion as to the shape representing a type ideally, and as to shapes that can be interpreted as realizations of such type, in spite of their not exactly matching the ideal type, a confusion that could aptly being named as the ›Morellian twilight‹, a confusion as to the question if the Morellian approach was about stereotypical shapes, that is: about something exactly and precisely matching, or about something matching ›more or less‹; compare also Cabinet II).

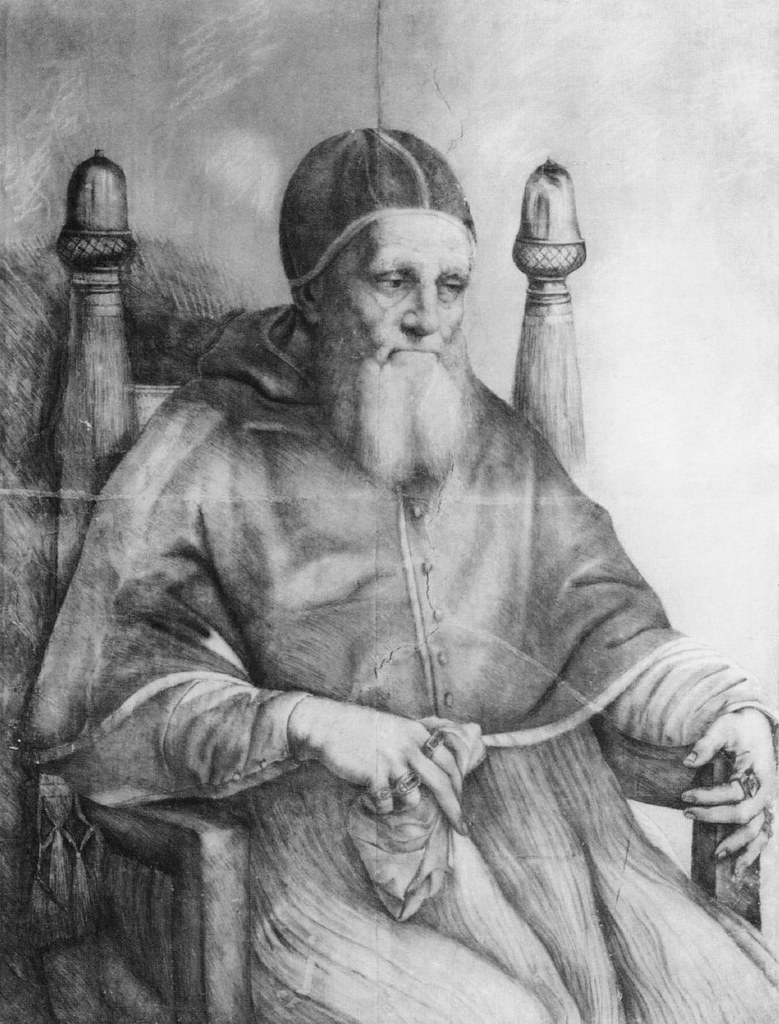

But these excuses cannot be accepted any longer: because for one the tools to check empirically are available (and have been available for a long time); secondly it would be mere ideology to further speak of Morelli as a foundational figure of scientific connoisseurship, if, as to central claims, these claims were found to be totally unfounded, and one would have to turn to speak of Morelli as a charlatan, at least as to this one central claim of a Raphaelesque ear, or at least of him being totally mistaken in this one case, or of him wanting to fool us with speaking scientifically, while actually producing, maybe deliberately, mere nonsense; and for three: the question does matter, at least if we are interested to discern four portraits of Pope Julius II and to find out how these four versions of a portrait might be possibly related to each other. This had already been our concern in Cabinet I (but only marginally), and Cabinet I had also introduced a Morellian situation, which is not to be equalled with any problem of attribution, but with the very specific situation that for example we might been confronted with four versions of a portrait of Pope Julius II.

(TWO) DID MORELLI SAY AND SHOW ENOUGH IN THIS PARTICULAR CASE?

I am developing a personal view here, and I’d like to say right away that I find Morelli not very convincing in his speaking of a Raphaelesque type of ear. This does not mean to dismiss his approach at all (which, anyway, can be regarded as one representation of style criticism with a scientific claim, and it would be absurd to dismiss the one representation or what it does represent, just because in one case we find him not being totally convincing). But I do recall that when I looked at my own visualization, juxtaposing those examples that Morelli does refer to, and, in addition to that, the one example that Morelli did choose to illustrate his words (that he chose instead of saying more, one has to stay aware), I do recall that I actually was rather surprised. Because, on the one hand, it seemed perfectly clear to me now, that Morelli never had spoken of stereotypical details when referring to characteristic shapes, although a mainstream interpretation seemed to have assumed exactly this: that it had been about tiny details, stereotypically rendered. But these ears, at first glance, seemed not to have much in common. And I turned to check what exactly Morelli had said about the Raphaelesque ear that he chose to describe as being round, fleshy, and intimately (or firmly) intergrown with the cheek.

After studying these ears for a while, after searching for exactly those features, it seemed to me that I could at least understand what Morelli was talking about. ›Fleshy‹? Yes, ›fleshy‹ might be an apt description of the distincly sculpturally rendered antitragus structure (I am using this experts’ terminology now, because it is necessary, and one would not understand what I am talking about either if I would not). I can see a fleshy, sculpturally modelled antitragus structure in all three examples; and I would accept if one would now begin to construct a Raphaelesque type of ear, building on this particular feature, and also showing the two other features named by Morelli. But still these features, in real examples might differ rather drastically, and I do find that Morelli, in subsuming three examples under a common type, does accept a rather large variability. As to the fleshy antitragus structure, which might be described three times as being a sculpture, but still as a sculpture varying three times.

But what about the other features? It seems to me that with ›intimately intergrown with the cheek‹ Morelli does refer to all examples not showing a radical being distinct of cheek and tragus; the tragus growing out of the cheek, as the cartilage (which it is) would be simply a passage between ear and cheek, without showing to be a distinct cartilage, but seeming to be rather cheek skin.

What exactly Morelli does mean by saying ›round‹ I do not know. Maybe he is referring to the ear’s contour, or maybe he is referring to an overall round sculptural quality, and it does seem to me that he is not specifying this well enough. As, above all, he is not well enough explaining to his readers that it is not only about discerning painters’ personal styles, but about discerning type and phenotype (the actual realized version of a common type), and maybe he did discern this himself rather intuitively. But on the other hand he instructed people to draw shapes for him, he called (or wanted these shapes to show ›basic form‹, and he wanted this basic shapes even ›slightly caricatured‹, which probably means: exaggerated as to the main elements/features that made the type, but still: all this resulted with a confusion, a mess, that we are trying to entangle here (and this includes, as we already have done in Cabinet II, to ask, if those who did provide illustrations did actually understand Morelli at all). Because, if there was and still is confusion – the problems that are behind this confusion do not disappear if they are simply covered up by confusion. And we go on with naming those problems.

How does the Raphaelesque type of ear, in sum, look like: it does look, which means: it would look like a model made of three main elements, a model that would not hide its being a mere model made of three elements. For everyone to discuss, if an example could be interpreted to be a realization of the type represented by the model (and in a way, this was the theoretical claim, representing the inner notion of anatomy that Raphael had inside his head or mind, and was in the habit of externalizing, assumingly, if he did render ears, according to that notion, according to that type, but at best: more or less stereotypically, more or less according to a common type. Which I choose not to represent here myself, since I am finding that Morelli in his description was not revealing enough of how exactly he thought that type. While the principle of his working method is clear: from observing examples, that seem to show some regularities, we deduct a type (being a mere construction, but showing, above all, these regularities), and new examples, works in question, ears in question, we might compare with that type. To find analogies, and maybe to the whole type as an entirety. Or at least formal analogies as to single elements (as for example the fleshy antitragus structure). And depending on how solid such demonstrations are given to us, we might find this more or less plausible.

Having said that I am finding Morelli not totally convincing in his speaking of a Raphaelesque type of ear (and I believe that he knew this himself), because he is simply not revealing enough (and we might run in danger to think of accidental features as being characteristic features), and because of his working with, I think, all too few examples to finally and convincingly show a stylistic, here: sculptural or morphological regularity, that attributional studies might draw on. He did state himself (compare above) that he had said all too little, and I believe that here, we have to take him by the word. Since the pictures do not speak for themselves (nor unconditionally in support of Morelli).

But it is nonetheless worth considering now the case of the four versions of a portrait by Pope Julius II. To simply understand the proceeding of the method, even if, in this case, we find that the argument, in the end, should not be given much weight. It is about discussing of procedures here (and of becoming aware how shortcomings of method might, in worst case, turn into actual arguments, taken all too seriously), it is about having a test case, and not about deciding that case by playing the card of the Raphaelesque ear (which in our opinion is not to be equalled with an ace here), which, as repeatedly said before, was not Morelli’s claim anyway. It was about finding something that may be of help. It might not be of much help here. It might be of better help in other cases, based on more convincing demonstrations. But the case is still an apt case to see and understand how something might be of help, if, beforehand, it was found, that a stylistic regularity does, beyond any doubt, show in the work of a painter and as to that painter’s rendering of particular details. Whatever detail it may be, (and we should at all times also be prepared to replace ›ear‹ with something else, the ear’s morphology being also a mere test case).

The Städel version: with no fleshy lobe, nor fleshy antitragus structure,

and with little sculptural quality at all

(picture: Google Art Project; detail)

The Pitti version, attributed to Titian (not being particularly dedicated, perhaps, to ear likeness

but maybe rendering his, according to Morelli, characteristic C-shaped ear) (source: Sander (ed.) 2013, p. 75; detail)

(THREE) THE RAPHAELESQUE TYPE OF EAR AS ARGUMENT? – AN EAR PARADE

What it is striking, if now we are looking at four versions of a portrait of Pope Julius II, is that the Pope’s one ear, that we are allowed to see, does differ in every single case. Well, there is only one original, one might say, and at least the one painter who actually did portrait the real person, and being obliged to portrait likeness, did render the actual ear of Pope Julius II, thought of as the real historic person. But if three other versions are to be considered as workshop replicas or copies, we now might say, then Morelli indeed might have a point in referring to the ear as something to make a difference, if attributing these replicas or copies to workship assistants or copyists. Because, obviously, none of these felt obliged to copy portrait likeness of the original to perfection, which means here: to the shape of the ear, which, as said, does simply differ in every case. Does here, we ask with Morelli, painter’s individuality show more clearly than it may show if we only would compare the Pope’s countenace?

We have to stay aware that Morelli did consider quality as well, the informed Morellian in us does remind us, but he indeed would have pointed to the fact that opinions as to the painterly quality that in the Pope’s countenance does show are simply divided (as Morelli would have expected these opinions to be divided), and this exactly had been the reason why he had suggested to look for something to control our general impression as to the painterly quality. Something to check our first glance impression, as our or Morelli’s scepticism does remind us, something to attain a higher degree of certainty.

If only we would know how exactly the Raphaelesque type of ear does look like. Since, as said above, we might compare a relatively vaguely defined type with all four portraits, or only a simple feature like the antitragus structure in all four portraits with what we do think Morelli thought of as being the Raphaelesque type. But, as also said above, this might result also in exactly bringing in the fuzziness of only vaguely defined properties into another discussion. Associated with whatever claim. And it is not the procedure as such that we would suggest here to dismiss, but the introducing of an argument that has not solidly been built (relying on more precise definitions and on a greater number of examples).

If, but only if, we would have come to the result that, unmistakenly, only one portrait of four did show, unmistakenly, the Raphaelesque type of ear, as, what would also be striking, also the portrait of another Pope, namely of Leo X, would show, the portrait of another Pope coming from another family, we would certainly be most impressed. Since this would be indeed, while we are empirically testing the application of the Morellian method, a strong argument in favor of the Morellian claim: that a characteristic anatomical or morphological feature did show even in portrait (and if a painter was committed to portrait likeness), and this, even more impressive, as to the portrait of two Popes, coming from various families. May everyone be invited to check this, and all of the here said, on her or his own, and above all visually, and critically as Morelli does deserve it.![]()

The London version: perhaps a realization of the round Raphaelesque type with fleshy antitragus structure

(also the shape of shell might be compared), resulting with us asking cheekily:

are these two Popes, Leo X (de’ Medici) and Julius II (della Rovere), yet related to each other?

(picture: Wikipedia; detail)

The Uffizi version with a particularly fleshy, sack-like lobe

(source: Sander (ed.) 2013, p. 74; detail; compare also Morelli 1890, p. 69f.)

And another question, an issue that indeed we are neglecting here, but a question that should nonetheless be raised as well (after its having been raised at the day of Morelli): are all ears in one picture, despite their seeming variety, built on the basis of one and the same type? Or might such a mere impression be due to the mere fact that all cardinals were in fact cardinal nephews and thus coming from one and the same, that is from the Pope’s family? Which would, possibly, mean that the alleged Raphaelesque type of ear would rather be a Medici type of ear (for Morelli speaking on the portrait see Morelli 1890, p. 69f.).

*

A (BURLESQUE) VERNIAN VISION: MACHINES TURNING TO BE CONNOISSEURS OF ART

The also debated Chatsworth drawing

(picture: flickr.com)

Detail from a cartoon to/after the Julius II portrait

(see also the small picture on the left),

attributed to the workshop of Raphael (Galleria

Corsini, Florence) (source: Sander (ed.) 2013, p. 76; detail;

compare also p. 52f. (Jürg Meyer zur Capellen)

for the issue of the workshop of Raphael and its history);

whoever might have worked after this scheme,

might also have sculpted out, in painting,

the ear of the Pope in his respective individual way,

providing us, possibly, with a clue;

and with our last example, meant to illustrate

as well as questioning the Morellian way of thinking,

as well as also artists’ workshop practices,

we conclude our ear parade.

(Picture: flickr.com)

According to Jules Verne expert and biographer Volker Dehs, the French writer is less to be considered as a prophet of future technologies than as a careful observer of trends in contemporary technology, that is the technological innovations and projects of his own time, the 19th and the beginnings of the 20th century (Dehs 2005, pp. 247ff.).

And there was something typical in, something characteristic for Verne, who did address issues of the natural sciences as a layman. Again according to Dehs: Verne did ›cautiously extrapolate‹ (p. 259).

Which is what we might be trying here as well: cautiously extrapolating, while observing the advancements in contemporary art historical technologies, in Technical Art History of our day.

Maurits M. van Dantzig (1903-1960),

(more or less) known for a quantitative approach

to applied style criticism and for the purpose of authentication,

but also and particularly for his putting a focal point on

artists’ ›handwriting‹, that is: on brushwork and

on patterns of brushstrokes

(source: Van Dantzig 1973, cover sleeve)

What we can observe is that image processing tools have come into use in recent years, at least in an experimental way, and this as regards the problem of artist identification (see for example Hendriks/Hughes 2008; Johnson, Jr. et al. 2008).

The problem »seems ripe«, we are told, »for the use of image processing tools« (Johnson, Jr. et al. 2008, p. 37). And this sounds as if a scientific community has long dwelled on the problem of artist identification and has now come to the conclusion that newer, better tools would be available.

Resulting with journalists, probably for the very first time in the history of mankind, referring to the computer ›as a connoisseur of art‹ in 2004, since a computer, not all by itself, naturally, seems to be able to recognize (what one has told him to recognize) and to quantify (what one has told him to quantify).

The attention of specialists does focus on the machine and on the new tools, and one cannot help to think also, that it would seem very welcome to hand over as much responsibility as possible to a (seemingly objectively looking) machine.

Only that any problem of interpretation will return (unwilling not to bother the human connoisseur). And it will return in shape of the problem to interpret, whatever the results of comparisons are that one has told a machine to perform, and to draw conclusions from that results.

Style, as it seems and perhaps only for the time being, has been reduced to painters’s style of brushwork, which is, metaphorically speaking, to be considered as the artist’s handwriting; and one does hope to be able to work with ›typical‹ marks, as far the brushwork style of chosen artists is concerned, and put under scruteny, in that wavelet analysis is being applied.

We are reminded of the Morellian age, not by image processing specialist who seem not to be aware that a history of applied style criticism does already exist, and that one could draw on the experiences, accumulated in and by that history. We are being reminded of the particular problems that already the age of Morelli has been concerned with: of what exact nature are these marks, these properties that one does consider as being promising, as regards the identification of artists: are these properties just typical, that is often occuring properties? Or are there distinctive properties to be found? Occuring in one class of objects alone, as exlusively and unique properties?

Because any human connoisseur, confronted with the task to interpret the result of machines seemingly objectively looking, does need to know to weigh the evidence.

And in what situations would one prefer to work with marks found in individual painters’ brushwork style (quantified marks, or qualitative, formal marks)?

Because if it would be about the problem of identification as such, one would not be well advised to give one particular property that much weight, if it would be only a typical property (recurring in many classes of objects and not just in one) (compare Cabinet 2, question/answer No. 17).

And if it would be about the discerning of intimately related styles (that of Van Gogh and that of his imitator Schuffenecker, for example), one would not be well advised to work with something that one has not specified as being ›distinctive‹ or only as being ›typical‹, or ›characteristic‹.

Since we have shown, in our Cabinet II, that what is considered to be ›characteristic‹ by one side, might not be seen as being so by another; also since there are various ways to understand the very term; even if it is, above all, one precise meaning that is on everyone’s mind: the uniquely being characteristic of something; the one property, if being found, being fit to decide, with mighty authority, over questions of attribution or authentication in art; as if this one property was deciding all by itself (without anybody performing any act of interpretation); without the art historical community or the wider audience (nor the other participants of a market, if for example we would be the participant of a market, and if we would claim to have found something uniquely being characteristic) having to raise an objection. Because all would be surrounded by a rhetoric of scientific objectivity.

Which would also be something a connoisseur with a historical conscience might be well advised to consider. In history. And particularly in the history of 19th century scientific connoisseurship.

It does seem striking that no interest at all seems to exist to make use of the experiences with and in scientific connoisseurship, albeit this subculture of connoisseurship indeed has never established institutionally. But this lack of tradition in connoisseurship, all too obvious in that style, all of a sudden, can be reduced to brushwork, probably finds its expression in a suddenly occuring technology oriented, but historically uninformed modernism.

And in the following we would conclude the present Giovanni Morelli Monography in doing three things: We’ll assemble, immediately following, some dates, crucial as to various technological trends that obviously have or could have a bearing on technologically modernized connoisseurship in the near future. Followed by a short Vernian vision, a mildly sarcastic letting our imagination run riot, as to the future options in technologically advanced connoisseurship.

And we’ll come back once more to the problem of style on a representational level, and in the Morellian sense (thought as an individual’s imprint upon realistic representation, and thus serving, possibly, as a clue, concerning the problem of artist identification): We will look at two scenarios of Digital Lermolieff, asking how digital means could possibly be implemented in scientific connoisseurship, but we do discuss two scenarios, because we do not take it for granted that the world of artistic form is actually as the Morellian theory – and the Morellian practice, as far as this practice also might have turned to be an expression of ideology – wants it to be.

As we are completing the Giovanni Morelli Monograph (in 2015),

engineers of Facebook are into the development of a face recognition system called DeepFace;

while Google is coming up with a system called Facenet… (picture: thewestsidestory.net)

C. 1964: early beginnings of automated face recognition systems [whose efficiency, up to the present date, might be called controversial]

1973: philosopher Richard Wollheim, more than 80 years after Morelli’s death, expresses his surprise that there has been ›so little empirical testing‹ as to the Morellian method (Wollheim 1974, p. 190); he also muses (p. 192) about how the illustrations in Morelli’s book were to be taken, interpreted and to be applied at all (›as configurational or phenomenal models‹?)

1987ff.: PC-supported signature verification systems are being developed due to demand of major financial institutions [I am relying here mainly on the notes as to the company history of Softpro that Wikipedia, in 2015, after the company has been sold in 2014, still names as the world leader of this branch of technical solutions; signature verification systems have been developed as to the authenticating of signatures given on paper and, in the mean time also (but less relevant in our context) as to the authenticating of digital signatures]

1994: first automatic signature verification system goes into production

2003: Ivo Widjaja, Identifying Painters from Color Profiles of Skin Patches in Painting Images (University of Singapore, Department of Computer Science thesis)

2004: the computer is being named an ›art connoisseur‹ for the very first time (Neue Zürcher Zeitung; see: [gsz.] 2004) which refers to technologies presented by three scientists of Dartmouth College applying wavelet analysis to analyze the brushwork of chosen painters

2011: the art historian and curator Anna Tummers (Tummers 2011) does refer to the above mentioned technological developments in her The Eye of the Connoisseur [thus the new technologies, at least here, are in discussion also in the academical art historical field]

2012: according to a newsreport (Neue Zürcher Zeitung am Sonntag) researchers at Lawrence Technological University of Michigan have taught a computer to compare paintings by 34 artists [from the one newsreport I got, it does not get quite clear what the machine was actually able to do and why; apparently the researchers were able to teach the machine to recognize similarities [which ones?] in works by Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico; and the press interpreted this as the machine being able to ›recognize‹ that works by these artists show a ›comparable style‹ (to whatever similarities this might bear on); I am including this to show that also informations are given in circulation that I would describe as being rather ›suggestive‹ than really informative, and that probably were made known rather with the aim to entertain than really to reflect what’s happening on this front of technology and why]

2014: wavelet analysis being applied to paintings by Vincent van Gogh is also an issue at the ›Authentication in Art‹ conference held at The Hague

2015: DeepFace, Facenet and The Digital Lermolieff

2015/2016: Christopher J. Nygren of University of Pittsburgh thinks about ›Giovanni Morelli, Or How to See a Renaissance Painting Computationally‹

And now we may allow our imagination to run riot. As we imagine a future fair of technical art history.

And it does seem to look like any other machine park, of any other technology exhibition. And the one or other device we have seen, well, it does remind us of 20th century microwave ovens.

But far from that.

Since we are laymen, one does explain to us that, what is looking like a microwave oven, is indeed a device (using non invasive technologies) to determine when exactly (or approximately) an art object had been in the making. Since, automatically, that is, by automatically comparing materials identified with known timelines of materials knowingly being in historical use, the device does exlude for example that a particular object could be an old object, or an ›that old object‹, if in fact materials were found that only later came in use.

This seems very smart. But another device is now explained to us: that looks more like a 20th century playstation. While, if fact, it seems to be a device that automatically analyzes the movements an artist had been doing, while producing a work of art. And on screen, well, reminding a little of 1980s computer game graphics, does appear a visualization of the artist at work.

This looks funny. If not very enlightening (it does occur to us while speeding up or slowing down the simulation of the artist, actually, as it seems, designed after an old master, at work).

But, as it explained to us, the visualization is meant to be only the show side of the device, while, in fact, it does rely on wavelet analysis and distinctive patterns of artists movements found in paint or drawing.

We ponder the questions raised, as we go on with our walk. And as it is also explained to us – but whom to rely on? – wavelet analysis does not seem to be that reliable as early producers had imagined.

Now we are turning to the more avantgarde side of the exhibition, that is more to the margins. And there a device is shown to us that, allegedly, has stored all the known ear shapes of Popes, and based on that visual database seems at least to be capable (still being in an early stage of development) to determine whether a particular shape of ear is that of a Medici Pope or not.

Another device, but we feel, more and more, like walking around a 21st century Biennale, promises to distinguish works of arts, if shown to the device, at least it does seem capable to name artists. But it turns out that the device is actually being offered by a Biennale artist, and what it does is using a random generator, not only to name artists, but also to associate artists with certain -isms. And the artist being responsible for that is actually to be associated with the very puristic Neo-luddite swing rioter artistic movement, being eager to expel technology from art at all, wherever it might seem to be found (with having also a foot in art connoisseurship, being eager to infuse a similar ideology to art connoisseurship as well, basta vedere, as it appears, being brought to a new level).

A few areas, by the way, we have not been allowed to visit. And it does seem that various – very exclusive new technologies – have been monopolized by, well, either very distinct circles of the art world, or rather very exclusive circles with more worldy aims. And we finish our tour with taking a Bellini.

*

ANOTHER VERNIAN VISION: DIGITAL LERMOLIEFF

Generations of art historians seem not to have been bothered

about the summary of the Morellian method by Sigmund Freud

in his 1914 essay on the Moses by Michelangelo (Freud [2000], p. 207;

Freud [2006], p. 282f.) actually containing three questionable elements.

And one may go as far as saying that Freud actually did misunderstand

Morelli (with many art historians also misunderstanding Morelli):

First of all it is one of the typical misunderstandings to say that

Morelli allegedly had his followers disregard the general impression

(or one’s intuition), to focus on marginal details alone. Which is only true

(compare Cabinet II) as far as Morelli did recommend not to rely

on a general impression alone; but since his method was meant

to control hypotheses won also by intuition, one cannot say that

Morelli had his followers/readers disregard a general impression

(Freud uses the verb ›absehen von‹), all the more one’s attention

may shift between the evaluating of a general impression and

the evaluation of a detail. But as we have said, Morelli did try to dispel

this misunderstanding only timidly (see Cabinet II and chapter

Visual Apprenticeship III of our Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography),

and one has to make him partly responsible for many readers getting

a questionable or false impression by reading him (even if many of them

did read him only partially, not being able to follow his timidly dispelling

of misunderstanding).

Secondly it is rather optimistic to say that

Morelli taught to discern original from copy ›with certainty‹;

at least, if this were so, one had also to ask why the Morellian method is

considered generally as being of no actual relevance anymore by most,

albeit not all art historians.

The third questionable element bears on the assumption

that we do discuss here again (which is also why we discuss

the famous summing up of Morelli by Freud in this Cabinet),

and it is the assumption that distinctive properties exist

that are characteristic for single painters (alone). Freud does

speak of marginal details that every painter does carry out

in a characteristic way; and he does leave it to the reader

to figure out if this means ›exclusively characteristic‹ way.

This is, on a very abstract level, the problem of any

classificatory system, also in the realms of psychology and psychiatry:

is there something telling, something uniquely characteristic, that actually

would allow us to identify something as being part of one class

of objects only, by relying on that telling distinctive property alone?

Or, as we assume here in our second scenario,

is there only fuzziness, upon which a suggestive classificatory system,

redolent of positivism, is forced on a reality, being actually

much more fuzzy than the theory underlying the classificatory system

would actually like to see it to be?

And if we would come to the latter conclusion, we would have to raise

the question subsequently of how much ideology we do find

in Morellian theory and practice, as well as in psychoanalytical

classificatory interpretations, that, because of Freud having found

some inspiration in Morelli, have to be seen, historically, in relation.

(Picture: Serge Melki)

If we assume, for a moment, that the world of art, the world of artist’s practices, and particularly the world of form, was exactly like the Morellian theory wanted it to be – this vision would look like an invitation to conceptualize, to renew the Morellian thinking digitally.

If we would pause now for a second, would come to our senses, to realize that the world of art is probably not exactly like the Morellian theory thought it to be, desired it to be – this might come as a disillusion. But still, it is another invitation to conceptualize the Morellian thinking digitally. Because at least this would help us to find a measure to what degree the Morellian thinking, applied in the individual case, does actually serve the connoisseur in the invidual case.

But we should like to consider the first scenario first: let the world be like the Morellian thinking wanted it to be: artists with distinctive artistic personalities uttering characteristic forms, that is shapes, typical shapes, distinctive properties, because every distinctive form does belong to a particular artist only. A world, if we would put it in modern terms, without fuzzy logic, without fuzziness bothering the connoisseur, and therefore: no fuzzy logic bothering the computer, the machine, the modern connoisseur’s tool.

I am putting the Giovanni Morelli Monograph together at a time when the advocates of technology promise to close the gap. Which gap?

The gap between human beings being able to recognize faces and machines being able to do the same thing.

An attentive reader of the present monograph might now say: wait, this is not the same thing. With the Morellian method it is about the identification of an individual artist’s stamp upon form, and not about the identification of real people. Real people that do not change in principle (except that they grow older, show tired or fresh, fleshy or starving, change clothes, use all kinds of mimicry, remodel their body stylistically and, well, bodily etc.).

Quite right: still the engineers of Facebook promise to close the before mentioned gap, due to face recognition techniques that are based on three-dimensional modelling of faces. And if they show to be able to close the gap as to the recognition of individual’s faces, they show also able to close the gap as to the individual artist’s imprint upon form. In spite of there being a difference between a ›stamp‹ and an individual shape of a face. But this is a matter of what learning routine is being used on the machine. And on what exactly the machine is told to do. If regularities are to be found, formal regularities, unchangable elements (in combination with variable elements), it might be that the gap between human beings working with formal regularities and machines, doing the very same thing (if being told so), is indeed about to be closed.

We speak of learning routines, since the machine has to be said what exactly it is meant to recognize. It has to learn about the individual’s face first (or about the individual stamp); it has to learn about structures and processes that might disturb the learning as well as the subsequent interpretative process; and it does complete its learning process by constructing a model (or in the Morellian language: a basic type); and – again: by using three-dimensional modelling techniques, as probably Morellian connoisseurs were using in their mind as well – it does compare. Resulting with matches, or degrees of matchings, probabilities of matching, depending on how such systems are elaborated and operated.

But now our attentive reader has another objection: With the Morellian method it is not about something remaining (relatively) unchanged as a face; it is about realizations of a particular type (being inherent to the artist’s mind) that the artist indeed does externalize, but in variations, with slight differences, accidental additions differently etc., even if a machine shows being able to work in the third dimension, with constructing three-dimension models from just two-dimensional images.

And quite right and well observed, attentive reader, but: besides the fact that faces do change as well, it is about the machine taking notice of these differences, slightly different interpretations of a type as well. And if the connoisseur is being able to do that, as everyone seems to assume, the machine shows being able as well. Telling the typical from the accidental etc. If the engineers of Facebook (or other engineers) indeed will show being able to close that gap. By, among other things, acknowledging the old problem of variance (for which one has used, since the day of the Renaissance, the metaphor of handwriting, and perhaps one might draw from the experiences with signature verification systems as well) as well as many other problems the art historical tradition has never dwelled on much, apparently taking for granted that connoisseurs might have done all this well, and certainly better than any machine of their day. (While on the other hand one may think that the advance in technoloy, brutally, does reveal, how much has simply been taken for granted, and without having been critically challenged, accepted.)

But there is not a single reason why, if the connoisseur might use the Morellian method as an aid, why a computer application adapting the Morellian method should not be of use as an aid as well, since its capability of making precise comparisons, a great number of comparisons, of storing large number of pictures (in his memory, his inherent connoisseurial musée imaginaire, if one does like so), of going on, day and night, in making continuous progress in his learning routines, eliminating the accidental from the typical, there is not a single reason why a machine, by principle, should not be able to carry out assorted routines (which, again, is not the same thing as replacing the intuitive assessment of a picture).

And this does not mean at all neither that the computer is meant to replace the connoisseur, but: the routines that are inherent to the application of the Morellian method a computer can perform as well. And perhaps: faster, more precise, in one word: maybe even better than a human connoisseur. And perhaps even better if machine and connoisseur show being able to work together well.

All depends, of course, of the quality of a) the material from which the computer is allowed to learn; b) from the quality of the model (or type) the computer is able to create, drawing on the whole body of reference material and c) of human beings telling him how to interpret results.

In simple words: what does it mean precisely if there is supposed to be a match? To what degree a computer has to tolerate variance? What is the exact definition of match, comparing, shape, type etc. on the most basic level?

But this reminds us only of the fact that – this is the question with any Morellian connoisseur as well: do we interpret something as a shape matching, what we believe to be a Raphaelesque or Leonardesque type of shape? And if yes, what do we make of that, knowing that we have just interpreted something as something. We, and not a machine (and perhaps with our wishful thinking interfering). We. Relying on memory capacity, acute looking, and perhaps – on Morellian theory.

If indeed we are relying on Morellian theory (like in the present scenario). Because it is just the fact that one has to tell a machine what to do, that serves us well to remind us that this process is ever about the interpretation of things. And even on various stages of the process.

The big question is the question if stylistic regularities of the Morellian type do indeed exist in art (and as he have said, Richard Wollheim found it rather strange that so little testing has been done).

If regularities indeed do exist – this would also mean that artistic style would be indeed something ›natural‹, allowing – even – a machine to recognize natural regularities, and to recognize regularities that allow to work with formal analogies. Within classificatory processes.

(Picture: molochronik.antville.org; Grandville)

If only artists would show to be that natural.

And one simple criteria might also serve as a measure of how good the Morellian theory actually does describe (or match) the actual artistic reality. Because, one may say, the more often our machine has to ask us how to interpret the result of a comparison, the more often we are being reminded – and now by our machine – how many decisions have to be made. Decisions about interpreting something as something. And the more often such decisions occur, the more vulnerable, the less reliable also, seems to be any working with formal analogies. And particularly: if classificatory processes are at stake (as well as high values, ideals not less than money or other material goods).

If we now go on to envision a second scenario: with the world of form being much more fuzzy than a Morellian connoisseur describes or suggest it to be, we would have to invite a Morellian connoisseur to protest: for example the Bernard Berenson of 1893, suggesting that the new science of connoisseurship, given that photographs would be used, almost attained the accuracy of the physical sciences (Kiel (ed.) 1962, p. 70).

Well then – we use photographs; and as important: we assume that we are disposing of face recognition systems ready to operate, which means also: that they await to be taught what exactly the system is meant to recognize.

We would sit in front of a large screen, and it would be our aim, in cooperation with Bernard Berenson, to create the model of a Raphaelesque ear. Told by Bernard Berenson what exact part of a Raphaelesque ear we would have to consider as being typical, specific, distinctly being specific.

Resulting with, ideally, a three-dimensional model of an ear, showing all the typical features of the Raphaelesque ear, while the accidental factors would have been eliminated; a model, derived from all available renderings of ears, already being considered as being unquestionably authentic.

Thus we would allow Bernard Berenson or another Morellian connoisseur to dismiss our scenario: by showing that stylistic regularities in fact do exist, and by helping the system to learn in its learning process, to be able to perform the routines of recognition as well as a human connoisseur is being able to perform such routines.

Which could be tested in that a face recognition system would be asked to sort Raphaelesque renderings of ears out from a large body of Perugino and Raphael renderings of ears. And if such would be possible, it could be shown that, given the specific Morellian situation (two or more intimately related styles), the shaping of ears indeed would make a difference, and, if not being considered as being a distinctive property all by itself, deciding over a question of attribution all by itself, it still could be considered as being a valuable clue among other clues.

But in fact, as we do assume, Bernard Berenson would never have had accepted our invitation, although he seems to have regarded himself being a Morellian also much later, albeit in an often highly ambiguous way (compare for example Provo 2010, pp. 64ff.).

Since Berenson would not have allowed his reputation as a connoisseur – indirectly – to be tested, in that he taught, and by teaching revealed, based on what sorts of comparisons he did work.

And, in fact, Berenson never granted much insight on what exact comparisons, be them Morellian comparisons or of another type, he based his attributions at all, never providing any documentation. Resulting with many people believing that what made a difference could not be explained at all (which Berenson himself denied), and that it was about quality and a refined sense of quality in the first place (which is actually where Morelli had started, with saying that exactly this was not enough, and that to attain a higher degree of certainty one had to do more).

But it is not about dismissing or not dismissing of the Morellian method here at all. Because our two scenarios both aim at the same thing: whoever does work – and does claim to work with formal analogies – has not only to claim it but to show it. At least in a scientific context. And as one would expect today: by using not only photographs but all the tools available that could improve visual management of classificatory processes.

In other words: if one would assume that stylistic regularities do exist, but perhaps not as the emphatic interpretation of the Morellian method wanted to be – it is still not about dismissing or not dismissing, but about looking at what in the particular case one does got. Series of examples, or only single examples of authenticated reference materials. A large body of examples or only a small one. And it is about looking, a scientific community would be looking, at every connoisseurs comparisons, formal analogies, and interpretations. Discussing subsequently the plausibility, the quality of the arguments brought forth.

With every connoisseur yet claiming to be an adherent of scientific connoisseurship – but now showing willing to reveal his or her actual reasons for or against a particular attribution –, with that connoisseur politely being reminded that scientific standards would expect otherwise. At least a protocol with stating that attributions were based on mere intuition. But if possible such intuitions being explored and explained, and if also checked on any level of style criticism and in detail, one would expect that not only single stylistic analogies would be shown, but also stylistic regularities that such building of single analogies would be based on.

Because this was exactly what, once and at least in its idealistic essence, the Morellian project was about: about finding something that would make a difference, given particular situations, and reminding and establishing of scientific standards, that include a systematic revealing of methods used, that had allowed to have come to a conclusion.