M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Dedicated to Claude Simon

How to deal with the Picasso myth today? One possibility might be to look at Picasso with the eyes of French novelist Claude Simon. Because the latter did include a memorable portrait of Picasso in his 1997 novel Le Jardin des Plantes, inspired by a meeting with the painter that took place in 1956. And while we are exploring this encounter and its literary echo, we will not only meet Picasso and Simon (and maybe Brigitte Bardot as well), but also two Chinese painters, searching for, or at least meeting Picasso in this very same year, not to forget, afterwards, the seemingly largely forgotten Ethiopian painter Afewerk Tekle. And while it might be that Picasso does look less big today, less big as a painter than he did appear, only some decades ago – why not thinking of Picasso just within a newly set frame of references?

A Picture Being Sceptical About Itself

One) The So-Called Issyk-Kul Forum’s Declaration

(Picture: artcritical.com)

(Picture: laprocure.com)

(Picture: contextes.revues.org)

Imagine that you are brushing your teeth in your bathroom. Your mouth full of foam, and your head still swirling of thoughts. And while you are brushing your teeth, while in the mirror you are watching your mistress or lover, seemingly being amused, and sitting on the bathtub’s edge nakedly and sharing the bathroom with you, and, as it appears, also listening to your trying to recall and retell all that weird stuff that you have just experienced in Asia (while your head is swirling of thoughts, and while your mouth’s being full of toothpaste’s foam, your thoughts, though confused, seem to be ahead of your words). – Experienced in Asia while attending a conference that did upset you tremendously, and with you as the conference’s black sheep, because of your not wanting to sign a declaration that was meant to be the visible sign of the conference’s output and the conference’s success, laying out a path into the future of mankind.

But because of your feeling that all of this, the whole conference, was just absurd nonsense, and just pretentious, and you were getting drunk, and you still were not wanting to sign (which might have cost, by the way, one of the interpreter’s his job, your not wanting to sign, and this one interpreter’s getting angry with you etc.

What we are imagining here is what the beginning of Claude Simon’s 1997 novel Le Jardin des Plantes is all about. That is: the author is recalling not only a conference but also his trying to tell his mistress or lover about it, while brushing his teeth and her sitting nakedly on the edge of the bathtub, listening to him with amusement. And Simon proceeds like a painter. And of course as a modern one, because what we are given is in some ways a fragmentary representation of something (the having attended a conference), but even more so a rendering of someone rendering something to someone, which makes the process of creating a picture transparent. And at the same time the textual fragments that we face as a reader, all taken together, still provide us with a fragmentary picture of what was going on at that conference in Asia.

The fragments could yet add up differently, and the past may look differently with every new view point and with every attempt to create a picture, for example if retelling our story while brushing our teeth (the toothpaste’s foam that we have in our mouth is especially significant here in its telling materiality, and one might call the literary techniques used by Claude Simon also a foamy toothpaste deconstructivism).

But what makes the extraordinary quality of Simon’s writing is, of course, that some of his fragmentary descriptions show in itself such a radiance and beauty, such a pictorial quality, that we are still impresssed by what language is still capable to do (with us), even if we find, as modern men, that a picture that would not be sceptical about being a picture would be a questionable picture, possibly wanting to impose something on us, possibly even tell lies, or at least wanting to impose on us a particular version of the past.

View from a Bishkek hotel (picture: tripadvisor.de)

To understand novelist Claude Simon really well, and he is and will remain a difficult writer, it is useful to know what his textual landscapes, being made of single fragmentary pictures, are roughly about. It is useful to know his recurrent references, even if no consistent pictures of what he is incessantly referring to might exist at all.

The conference we are referring to, the so-called Issyk-Kul Forum, was held in Kyrgyzstan in 1986, at the Issyk-Kul lake, just weeks after the Reykjavík summit of October 1986. It might be the Issyk-Kul Forum a marginal and hardly remembered episode of the Perestroika era (beginning in this very year with Gorbachev’s famous Perestroika/Glasnost speech given in April), but it is an episode worthy to recall, not only because it is one of the central motifs of Simon’s novel, but also because the whole episode of Simon being unwilling to be a signataire of the Forum’s declaration is such an interesting motif in itself.

The Forum itself (for some photos see here) has hardly left any traces in history, despite its large ambition, in other words: the world has never much notice of the Issyk-Kul Forum and its declaration, and one might raise the question if Simon wasn’t actually very much in the right in not signing something that in retrospect might actually look rather pretentious. And on a more general level one might also ask what it did mean, to be a responsible political intellectual then, and what it does mean today.

Mikhail Gorbachev, by the way, did welcome the 15 invited intellectuals and artists from all over the world in Moscow, for a short meeting after the actual Forum held at Kyrgyzstan, and we will come back to that episode as well.

A report on the Forum, provided by the Soviet journal Kommunist, was then translated by and for members of the Western »Defense community« (see the document here), and we can refer to this source, being sceptical about any picture, as a source that has been processed repeatedly, but it is still a source worth being taken into account, and be it only for the fragment that we will give below.

With this introduction we are prepared for Claude Simon meeting Picasso. But we still have to prepare for a meeting with the Picasso myth. And this means to go back in one’s own personal memories.

Two) Picasso As Seen By Edward Quinn

(Picture: pablo-ruiz-picasso.com)

(Picture: boekwinkeltjes.nl)

Picasso as seen by René Burri (picture: magnumphotos.com)

In my childhood I probably thought that being an artist meant to live like Picasso did live in his Cannes villa La Californie in about 1956.

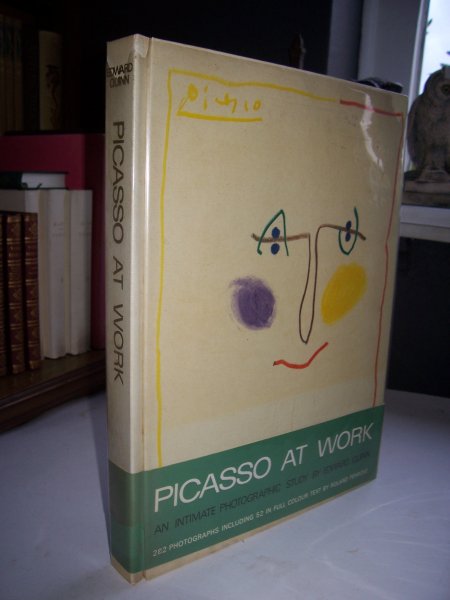

Because my first impressions as to what art was all about were very much influenced by looking at Edward Quinn’s 1965 picture book Picasso at Work (with texts by Roland Penrose). I still think that this is a magnificent book, but over the time I have, naturally, become suspicious as to the Picasso myth (and especially as for the role of children play therein).

But back then it seemed that art as such might as well have been invented at La Californie (and not in Ancient Greece or even earlier times); at La Californie where Picasso did reside (but I certainly did not think of it then as a »residing«), playing with his son and daughter and, all in all, showing himself (or at least seemingly showing himself) like a loving father or, because of his age, a loving grandfather. The image of my one grandfather might, to some degree have melted with that image of Picasso.

In any rate: this whole scenery of La Californie seemed to represent very naturally arts and craft in any imaginable way. And in that Picasso seemed to be a sort of grandfather on his part, a grandfather with a mythical status, as somehow was made clear by the many books and also by the numerous representations of works by Picasso that we had.

But over time a slight suspicion grew, to put it mildly, that all might have been a little different, which is not to say that the biography by Arianna Stassinopoulos Huffington does give the full or anything like a definite picture. But Picasso had other sides, that were not represented in the Quinn/Penrose book. His playing with children might have been very natural, but there’s also that one picture of Picasso bathing with his daughter Paloma, and with Picasso pointing towards – the camera taking that picture (with Palomo looking right into the camera’s lens).

(Picture: iexaminer.org)

And if one gets acquainted with Picasso literature, one does realize, over the time, that everyone who has left a memoir or written a biography, has, in one sense or another, been part of that scenery that seemed, seen by a child, representing what art was all about. Everybody – the Quinn picture book makes it beautifully clear – related to that one unquestioned center. Seemingly, because it now seems that this seemingly simple order was, in reality, full of tensions. And having realized this might be simply the equivalent of growing up (but does growing up mean necessarily waking up in any way?).

How to deal, thus, with the Picasso myth today and as a grown up (and how with the Huffington’s Picasso biography very in particular)?

As far as I am concerned the Picasso myth is still being strong, and my having difficulties with thinking of Gerhard Richter as being one of the bigger painters has probably something to do with it. Because creativity, for me, was identical with a Picasso-like seemingly exuberant creativity, exuberant in creating form, and I still find it difficult to do justice to very different forms of creativity, less exuberantly inventive, but – or also – inviting chance and working with – or reworking – already existing form and style (what Picasso, of course, did do as well, incessantly: inviting chance and reworking the formal languages created by others, and appropriating these or translating these into his own formal language; in that he seems less big today, but still more playful and artistic like an illusionist is being artistic).

When now, in about 1998 I came over Claude Simon’s novel Le Jardin des Plantes, it seems to me now that I did find something that might help to re-adjust a picture. To deal with the Picasso myth. Again. Anew. – Because Simon’s novel contains a description of Picasso’s household at the villa La Californie at Cannes, and it is written in a different tone, and displaying some of the literary tecniques that we have spoken about above. It is a literary memoir, recalling a visit, a meeting with Picasso in 1956, the year of Picasso’s 75th birthday. And it we think of all that Quinn and Penrose depicted in their 1965 book as a particular scenery – we can now think of this scenery as being a mere fragment, taken from one of a great writer and novelist’s textual landscapes. As a single piece from a writer’s landscape garden of memory. That also might have a fictional quality, and possibly hidden, in that here we face retranslations of something into another time’s language. But at least there seems to be a novelist at work who might show us how to shift perspectives and who may show us what it is, creating a picture.

And the following is about a shifting of perspectives. Claude Simon, might appear, for many, only as the Picasso sun’s sun dog in 1956. But we’ll see how this looks like in the end. And Simon’s recalling of his being a visitor at the Picasso household in 1956 allows, yet even demands to call, if possible, another witness: the one mysterious, but seemingly anonymous Chinese painter visiting Picasso, the one of two Chinese painters that did meet Picasso in 1956, this very year when Picasso already did live, if he wanted or not, within his own myth.

Three) A Senator’s Household

Claude Simon (picture: pinterest.com)

(Picture: fembio.org)

(Picture: pictify.com)

How to begin a portrait of Picasso? By speaking about his eyes? About his coal-black diamantine eyes?

Claude Simon does not exactly do this. He begins with speaking about Picasso’s »eye« (not ›eyes‹), about his »coal-black diamantine, alarmed, quasi scared eye« – but only after having compared Picasso with a rabbit.

This is in two ways a subtle strategy, because it goes for the reader’s surprise (by using an unexpected animal comparison), and by immediately going into detail. And this might be called also a slightly manipulative strategy, because what is striking about Claude Simon’s portrait of Picasso is just that it is not a picture that is sceptical about itself, as is the picture Simon gives us of someone’s attempt of giving a picture of the Issyk-Kul conference (while having toothpaste’s foam in his mouth).

With Picasso it is different. This is not about foamy deconstructivism, this is about defining a picture of Picasso. And in some ways, because the Picasso aura is so strong, it might also be called a defensive picture, though, paradoxically, it is not free of aggressive undercurrents.

Within Simon’s oeuvre the Picasso portrait of Le Jardin des Plantes stands for itself. It is possible that this passage that is only a couple of pages long might be the result of many attemps to give a picture of Picasso, but here Simon does not allow us to witness his repeated attempts, his strategies of image production and image processing. This is just it – the final picture that is not showing doubts about its being a picture, nor does it show very obviously how it is made.

At least not at the surface. Because two details make clear that this picture of Picasso – it might also be called a picture of Picasso’s presence – is actually a picture given in retrospect. The actual visit at Picasso’s household had taken place in 1956, but Simon speaks also of a future direction that Picasso’s artistic production is going to take. This is hindsight knowledge (the knowing about Picasso’s repetitiousness; his more and more coming back to the subject of the brothel and the whores).

And the aggressive undercurrent shows (also) in Simon’s (deliberate?) mistake in saying, while still referring to the 1956 visit, that this was the time of Picasso greeting Stalin. Since Stalin died in 1953, three years prior to this visit.

It is obvious that Simon is not very precise here. But what Simon does, is to (maliciously?) remind us that Picasso once sent greetings to Stalin’s birthday. And indirectly he raises the question that also Picasso biographers do raise: why not a more clear dissociation from the communist party, especially in 1956, the year of the Hungarian Revolution?

This is again the question for the artist’s political conscience. And the repetitive coming back to the Issyk-Kul scenario shows that Simon struggles with the very question as well, and faces the question, as a public figure, having won the Nobel prize, and now being invited to discuss issues of world affairs: what is the artist supposed to do, at a Issyk-Kul conference (beside enjoying it, if possible), and if being in the presence of General Secretary Gorbachev (and in some ways Simon struggles not only with Picasso, and with Picasso’s aura, but also with Gorbachev, and also with the conference’s the actual host, with novelist Chinghiz Aitmatov.

But this is not the place to follow the question for the artist’s conscience any further. It is about Picasso that Simon does compare with a Roman senator or patrician, surrounded by his clientele. Courtisans, flatterers, parasites, all in this ambiguous, lascivious, and yes: decadent Mediterranean atmosphere of villa La Californie at Cannes. And the place that Simon gives himself in all this – the place as the observer. Who takes notice that Picasso is visited by an old Chinese painter that Simon does not name. And who does not show actual curiosity to any of these visitors (the names or the no-names). It is about the presence of Picasso, and probably also about the question how to free oneself of this presence, be it as a painter or a novelist.

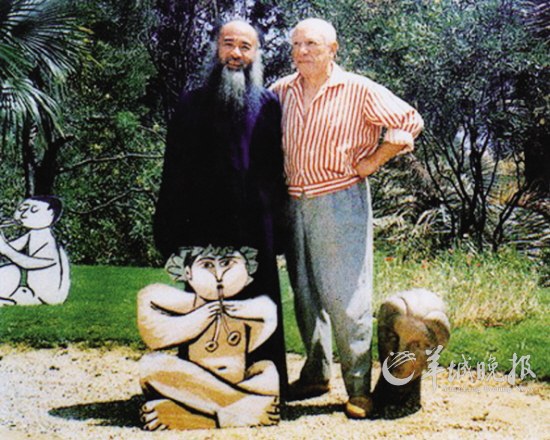

Picasso and Zhang Ding: the Chinese painter whose 1956 meeting with Picasso Claude Simon describes in his Le Jardin des Plantes was probably Zhang Ding who passed away in 2010 (picture above: china.org.cn); yet it remains to be clarified why Simon refers to a »white goatee« while in the picture with Picasso Zhang Ding shows beardless; according to Simon Picasso did welcome the painter only because »they sent him to me from Beijing« (which means: if he had come from Limoges he would have »thrown him out«); as to the gifts Zhang apparently presented Picasso with, some confusion does exist as well (Simon speaks of a »series of Chinese ink drawings« while other sources seem to speak of a work by painter Qi Baishi, whom Picasso is said to have appreciated; but in Simon’s account a bugged Picasso reacts rather aggressively to the gift in showing his own drawings and in saying »moi aussi je fais du chinois!«).

(Picture: szdaily.sznews.com)

Picasso and Zhang Daqian: given an ocean of print as to Picasso it seems no less than a disgrace how little is actually known about Picasso’s encounter (or several encounters: sources speak of Nice, Antibes and Paris) with Chinese painter Zhang Daqian (picture above: french.china.org); tradition, if taking notice of this memorable encounter at all, has usually focussed on the merely symbolical dimension of East meeting West (or vice versa); it is even possible that in some accounts Zhang Daqian and Zhang Ding (see the microportrait on the right) get actually confused; but who was Zhang Daqian, the man who is showing with Picasso on the photograph above? The legendary status of Zhang Daqian might be out of question, while it remains hard, at least for a Western general audience, to see one of the most renowned Chinese painters of the 20th century and the gifted master forger as one and the same person. Further research and expert’s explanations would be welcomed.

If Claude Simon, or the studying of Claude Simon’s strategies as a novelist, helps us to understand that giving a picture is not giving a picture, it is because he uses this two strategies that are obviously extreme opposits. One might deconstruct Simon’s portrait of Picasso like Simon himself deconstructs the image of the Issyk-Kul Forum; and one might define the image of the Issyk-Kul Forum in retrospect, by challenging the idea that a picture has to be at any rate sceptical about itself being a picture.

And if he have understood these fundamentals we might finally turn back to Edward Quinn’s Picasso At Work, because this book offers, we realize it only now, a simple possibility, how to resonably deal with the Picasso myth: by just focussing on what Picasso does as an artist, in any given moment, at work, and maybe – if this is possible – as someone that we imagine as someone being as little known as the two Chinese artists are (in the West) that also met Picasso in the memorable year of 1956 (as to these two see the two microportraits to the left and to the right).

***

Postscript:

A short excerpt from the Kommunist’s covering of the Issyk-Kul Forum attendants meeting with General Secretary Gorbachev deserves historians’ attention in particular, because we find here a variation of the famous dictum (more attributed to the General Secretary; see for example here) that says that ›the one who arrives too late, gets punished by life‹:

»Heidi Toffler said that she was particularly impressed by the equestrian festivities in Kirghizia. She was particularly impressed by competitions in which a man tries to catch a girl. If he fails, on his way back the girl hits him with a lash. This is a rather strange but instructive custom. Perhaps it should be made more popular, she ended in the midst of a general laughter.

M.S. Gorbachev: Let us try to apply this metaphor to politics: if we prove unable to pursue the ideas of peace, progress and justice, we deserve being lashed.«

And see also here

*

(Picture: characterattack.files.wordpress.com)

And our curious readers might also be wanting to know what exactly Claude Simon was unwilling to sign. The declaration of the Issyk-Kul Forum was apparently published in: Soviet scene 1987: a collection of press articles and interviews, edited by Vladimir Mezhenkov, but I do not have a copy of that publication at hand.

And any reader that is into Claude Simon might be wanting to know who the fifteen invitees of that now more or less again famous Forum actually were. The participants, other than Claude Simon and the host Chinghiz Aitmatov (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinghiz_Aitmatov), were Federico Mayor (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federico_Mayor_Zaragoza), Yaşar Kemal (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yaşar_Kemal), Arthur Miller and Inga Miller (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Miller), Zülfü Livanelli (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zülfü_Livaneli), James Baldwin (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Baldwin ; apparently his brother David joined him), Peter Ustinov (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Ustinov), Alvin Toffler and Heidi Toffler (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alvin_Toffler), Lisandro Ortero (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisandro_Otero), Afewerk Tekle (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afewerk_Tekle), Alexander King (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_King_%28scientist%29), Narayana Menon (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V._K._Narayana_Menon) and Augusto Forti (http://www.ateneoveneto.org/structures/augusto-forti/).

For further reading we recommend: Rolf Vollmann, Akazie und Orion. Streifzüge durch die Romanlandschaften Claude Simons, 2004

and Claude Simon, L’invitation, 1987 (a piece of prose that deals with being a participant of the Issyk-Kul Forum more directly)

And Claude Simon did allow that the Picasso portrait within the novel Le Jardin des Plantes was also published separately, in German and in a journal. Read it here.

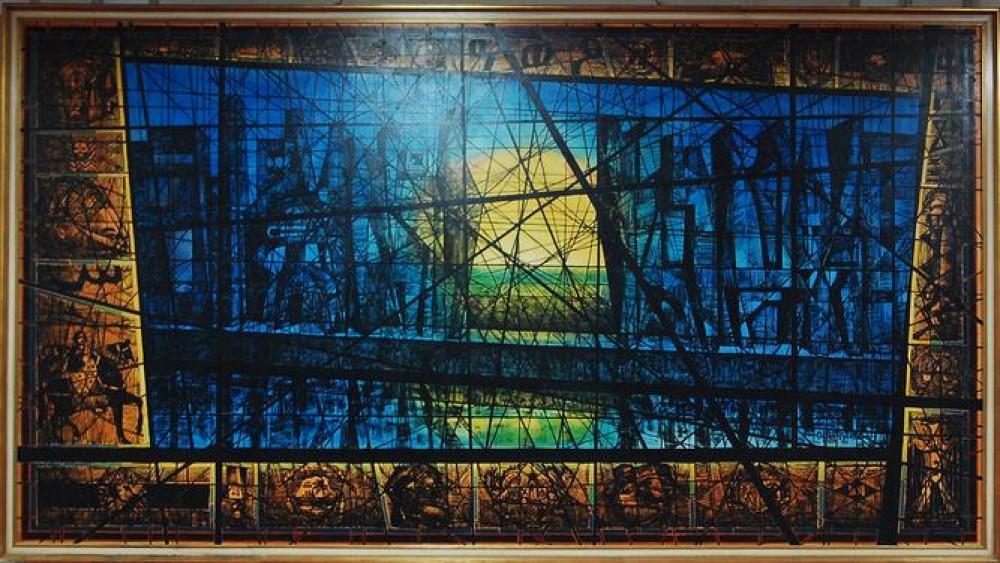

Afewerk Tekle’s African Heritage of 1967 (picture: ethiobeauty.com)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS