M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Ende Pintrix

When the Swiss publishing house Urs Graf-Verlag prepared for a facsimile edition of the so-called Gerona Beatus, one of the marvels of medieval illuminated manuscripts, it was arranged that this commentary to the Apocalypse was actually brought to Basel, where it resided with the »Reproduktionsanstalt« Fridolin Schwitter AG to photograph the codex. It might have been around 1961 that the »Druckermeister« Othmar Disler, responsible for the printing of the facsimile at Olten, lay awake at night for hours, according to the testimony of Titus Burckhardt, because of mixing colors in his mind, to get »the hue that we need«.

And if we go back now no less than about a thousand years we find the artists responsible for the production of this codex and its colors: an abbot named Dominicus who had it made; a priest named Senior who did write it; and a woman artist named Ende (or En), who, in cooperation with a Brother Emeterius, did provide for the illuminations.

This latter fact presents us with a particularly interesting problem of connoisseurship – the division of hands in early medieval art, the division of hands between a women artist and a man.

Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames or A Case of Gender-Troubled Connoisseurship

(Picture: elclubdigital.com)

(Picture: herstory-

pena.blogspot.ch)

Setting the scene might not be useless here: it is the time of the beginning Reconquista, the winning back of Muslim ruled Spain for medieval Christianity. At least: that’s one possibility to take a point of view. And the codex we are talking about might even be seen as one small element within the whole scenario of Christianity preparing for the Reconquista, or at least: of contributing to define the cultural athmosphere at the time of the first milennium.

But this is only one point of view, and, as we will see, this is also about things that might not exactly be as they appear at first sight. Yet the question might be allowed (it must be part of our setting the scene): how did it feel to be part of such an undertaking, as a woman, to participate in the genesis of one illuminated codex (like, as we know today, although the subject has been much neglected for very long, Muslim women artists, in their role as calligraphers, did participate in the genesis of some marvels of Muslim calligraphy.

But in the end we are left with setting the scene, because he know hardly anything about this woman: En or Ende. Was she of aristocratic birth? Was she familiar with divergent cultural traditions? Was she aware to be part of an undertaking that, even after a thousand years, is still being worth of being recalled. And: Was she, in any way, or in any particular way, familiar with Islam?

Well, as a matter of fact, we can’t answer a single one of these questions. And En (or Ende) will remain a name for us. But, at least and beyond question, it is the name of En depintrix (or: Ende pintrix), a name referring to a woman. And that’s it. Or is there still more?

Well, a few facts might be assembled, to set the scene a little further. To be part of the undertaking of winning back Muslim ruled Spain for medieval Christianity was probably not how it did feel, to contribute illuminations to a codex at the cloister San Salvador de Tábara in the region of Castile and León (which is where the codex was being made, and it is only kept by the Gerona cathedral and therefore named after this city). Because it is the time, when the codex was being made, at around 975, of numerous raids led by Almanzor, raids into Christian ruled territory. And in 985 the city of León was actually sacked.

And one detail is worth noticing: according to the calendar of the makers of this codex the year 1000 had already passed. They counted the year 1003 and it is the codex itself who says that these were times of war. It was finished, again according to the maker’s calendar, on a July 6, a Tuesday. Was this a day to celebrate and to rejoice?

Another question but no answer. And we won’t go any further into the history of Almanzor and the raids he led, but at least the question, again, must be allowed. How did it feel to be threatened by these raids? Is this a story that seems to fade away in the far distance of the first milennium? Or is this a story, very much reminding of the presence, i.e. is it an almost contemporary one?

(Picture: amazon.de)

Titus Burckhardt and his wife Edith (picture: DS)

I have come over this subject only by accident, because of finding a book by Titus Burckhardt, entitled Von wunderbaren Büchern, in an antiquarian book shop at Basel, a fine little book containing some recollections of a particularly interesting personality. And I would think of this charming book about the editing of facsimile as belonging to any basic bibliography of connoisseurship, just because Burckhardt does not speak as an academic (which he was not) but as a bibliophile, as a scholar of wisdom literature and not least: as the director of the Urs Graf-Verlag he does speak about the editing of illuminated books facsimile, not to forget the cultural encounters and also some adventures associated with this doing.

One does not realize, this might be added, that it is a Muslim speaking from this book. Because this is one side of Burckhardts personality (and also the reason why this personality worthy of being portrayed in a full biography has not yet found a worthy biographer): Titus Burckhardt, son of an artist, chose to convert to Islam (and in Protestant Basel this meant also a choice to live as an outsider, and the journalist Beat Stauffer, an expert for the Maghreb region, recalls, in his fine Burckhardt portrait of 1999, how Titus Burckhardt, whose Muslim name was Sheikh Ibrahim, did once enter the Confiserie Tea Room Schiesser (as the Café is officially called today) at the Basel Marktplatz – wearing turban and djellaba.

Basel understatement, however, does not directly react to such an appearance (except of, possibly, raising its eyebrows), but of course one did take notice that a son of the famous Burckhardt family had chosen to become not only an expert (or connoisseur) of the mystical strains within Islam, of mysticism, of sufism, but to become a Muslim himself, and not only that but a member of a sufi brotherhood.

Stauffer, who is very fair in his portrait, does not omit some critical questions as to Burckhardt’s maybe idealized image of Islam, but also reminds us that being a specialist for sufism does mean, from the point of view of radical, dogmatic and fanatic Islam, to be an expert of heresies. And at the time Burckhardt had actually turned to Islam, the radical and fanatic strains of Islam yet did exist, but played only a minor role as to the public perception of Islam as a whole.

Al-Azhar Mosque of Cairo was commissioned in 970, and the eponymous university founded in 975/988 (picture: islamic-arts.org)

When the Gerona Beatus arrived in Switzerland in the very early 1960s, the book was being brought to Switzerland by a member of the Gerona cathedral chapter, and being brought within a simple battered suitcase (and without any custom officer obviously taking notice of it or being informed).

The encounters with the members of the cathedral chapter are, by the way, just one example of why this fine little book by Burckhardt is still worth reading: Not because it would be about the up-to-date scholarship as for the history of these illuminated manuscripts, but the travelling across postwar England, for example, to prepare for a facsimile edition of the Book of Kells, allows to speak about these marvels of illuminated books as what they actually are: achievements of human civilisation, of human culture, that have, despite times of war and disruptions of human civilisation, survived, and in surviving all that was and is horrible in human mankind’s history, they represent human civilisation, and in a way that associates human civilisation with an immersing into texts and images, be it to produce these codices, or to respond to them as a reader and beholder, or – be it to reproduce them in shape of facsimile. And the following picture can be reproduced here, because it was part of Burckhardts book mentioned above, which, by the way, was also meant and being produced as a gift to the friends of the Graphische Kunstanstalt Schwitters AG, as a gift for Christmas of 1963.

(Picture: DS; source: Von wunderbaren Büchern)

(Picture: iconosmedievales.blogspot.ch)

Would Titus Burckhardt have been interested in the division of hands within the Gerona Beatus?

I guess that he would have not, but one can never be sure. The artist En (or Ende) who has been part of, as it were, the team to create or produce this codex does represent all that we choose this codex to represent. And of course, because of the participation of En/Ende, because of the participation of a woman, the codex itself does represent the question for the place of women within any tradition of human civilisation (and as mentioned above, this question, in regard to the traditions of Muslim calligraphy and the participation of women artists therein, have, after having been neglected for long, only recently been raised).

What we face here is a problem of connoisseurship, embedded in, of course, a major question. And if one likes so, one might also study the major question as to the place of women in art (and about their being allowed to participate, or their own chosing to participate) by beginning to study this very particular question of connoisseurship: is it possible to isolate the contribution of a woman artist within this cultural artifact that obviously was the result of collaboration? Or are we, while this is actually impossible, only confronted with attempts to set the scene, attempts that, by setting the scene, turn this setting the scene, due to preconceptions about the nature of women and man, into questionable historical truths about the nature of art, being made by a man, and the nature of art, being made by a woman?

In only raising the question here, we would also like to point to dealing with the question of a woman art historian. It is to be found within the En/Ende entry of the Dictionary of Women Artists which turns out to be, in this particular case, as containing a sort of tutorial on how to deal with this particular question of a division of hands, and it does, by the way, refer to a multitude of rather dissatisfying attemps that were obviously biased because of the before mentioned preconceptions:

»In spite of the fact that the Girona Beatus colophon names Ende specifically as a painter«, Pamela A. Patton writes in the Dictionary of Women Artists, »disagreement has persisted regarding the extent of her work on the manuscript. Many scholars have assumed that Emeterius, a male artist known to have worked on a previous Beatus codex, was the work’s primary illuminator, and have ascribed to Ende those illuminations displaying appropriately ›feminine‹ qualities, such as decorativeness, delicacy, and even spelling and grammatical errors […]. A more effective attempt to distinguish Ende’s hand, however, may be made through comparison of the Girona manuscript with the fragmentary Tábara Beatus of Emeterius and Maius, so that any contrasting features found in the former codex might be evaluated as the result of Ende’s intervention.

Whereas the Tábara illuminations are characterised by a predominatly warm palette and a restrained and delicate handling of form, the Girona codex often displays an exuberant colourism and formal vigour that might well be attributed to Ende. The Christological cycle that precedes the Girona text […] includes […] scenes showing the Flight into Egypt […], Illness of Herod, Christ Before Caiaphas, Denial of Peter, Crucifixion, Holy Women at the Tomb with Christ, Judas Hanged, Holy Women at the Tomb with Joseph of Arimathea, Descent into Hell and Resurrection, which are not found in other Beatus texts of the 10th and 11th centuries. These non-traditional scenes, apparently inspired by northern European precedents, thus constitute an innovation for which Ende might be credited. Although these suppositions necessarily remain speculative, they suggest that Ende’ significance stems not only from her status as one of the first known female artists in Europe, but also from her achievements as one of the most expressive and innovative painters of her era.«

The »more effective attempt« results with a speculative construction of an image of the painter Ende, responsible for the »exuberant colourism and formal vigour«, as well as the iconographical innovations. And while there is nothing to say against the mere logic of this passage, the author, Pamela A. Patton, knows that this result remains speculative. What, one might argue, if not the men stayed conservative, in other words, what if the men felt to do something new with the Girona Beatus? And where are the other works by Ende, to ascertain that the character of her work was indeed exuberant colourism and iconographical innovation?

Still one might say that this speculative construction of a hypothetical artistic personality was necessary, simply to oppose traditional constructions, based on mere preconceptions regarding to ›appropriate‹ male or female qualities. And to point to the danger that speculative result might in the end become fact means only to stay aware of a hypothetical danger. Because we have here, in nuce, the problem of a division of hands along or not along the construction of gender roles laid out. And one may summing up the problem (that probably is not to be solved in the end) with another hypothetical question: What, if the exuberant colourism and formal innovations were the result of a vivid interaction between all the individuals involved?

Travelling to Ireland in 1946: a Supplement

»Thus in the summer of 1946, together with the excellent photographer Rico Polentarutti of the Reproduktionsanstalt Schwitter at Basel, I drove to Ireland. Both of us won’t forget the journey across England, still lined by the war, since we had two heavy boxes full of devices and plates with us that, despite all of the government seals that shut them, we could get only with much labour through the United Kingdom.« Picadilly Circus in 1946 (picture: twicsy.com); below: Holyhead Port (picture: holyhead.com); Dublin Trinity College in 1946 (picture: pinterest.com; background picture: deaconcast.com) |

|

|

(Picture: pinterest.com) »I opened it and experienced something similar like a diver, discovering under water, in enchanting light, a whole world of coral trees, sea anemones and colorful fishes […]. Like the trace of a steadily rolling wave in the sand the script is sliding, and the smaller colored initials and ornamental letters stick to it like pearls, like rare shimmering shells and like gems that a royal ship, sunk in the sea, would have scattered there.«  |

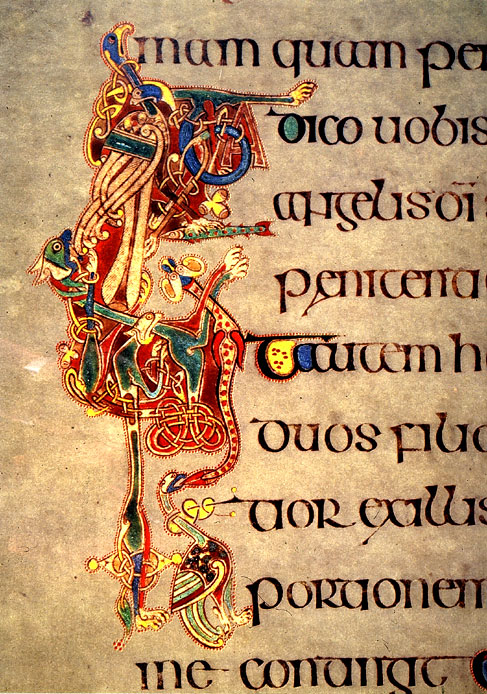

A decorated initial from the Book of Kells

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS