M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Explaining the Twilight 2

(Picture: Andreas Rabending Fotografie)

(Picture: Falkue)

(Picture: Photo after the 1961 Beckett portrait by Reginald Grey)

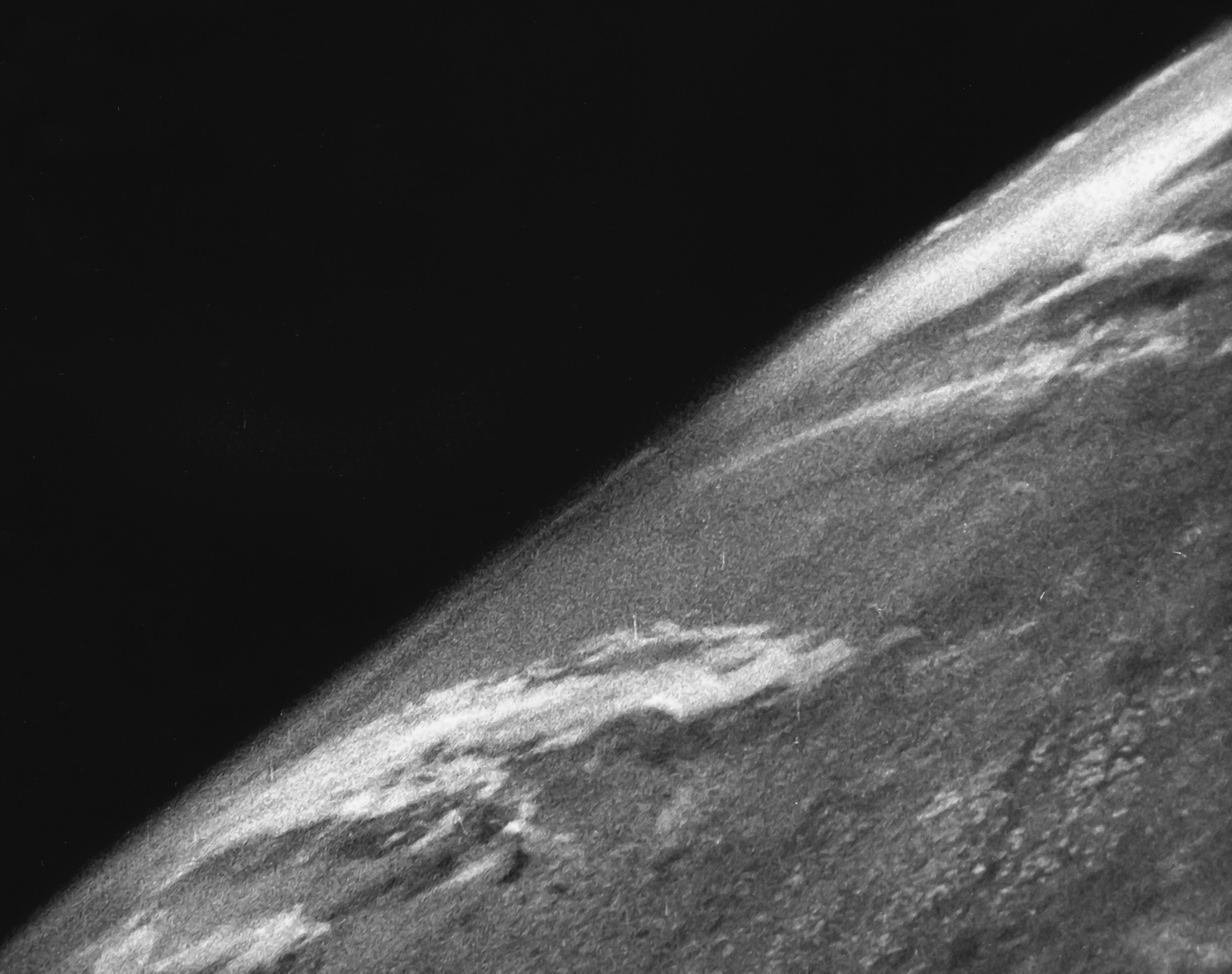

(Picture: U.S. Army)

(1.-2.11.2022) »Will you look at the sky, pig!«, Pozzo says to Lucky in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and Lucky looks at the sky, after which Pozzo goes on to give an explanation of twilight that oscillates between being poetic and prosaic. The one or other reader may recall Samuel Beckett from school – his play was published in 1952, and it premiered in January 1953 –, but who does know Edward Olson Hulburt? Because this scientist actually did explain twilight. Because Hulburt did explain why the sky was blue at dusk, and this in a publication, published only weeks after the premiere of Waiting for Godot. Does this sound absurd? Perhaps. But even more remarkable is perhaps to notice that the scholarship Hulburt represents was also helped by the V-2 rockets, developed by Nazi Germany, and available to US scholarship after the Second World War.

Not every human does want to know why the sky is blue (and why it remains to appear as blue at dusk). Fair enough.

But it seems that you want to know, dear reader, so I am assuming that, perhaps, you have been asked by a child recently why the sky is blue.

Or perhaps you have been asked by an already informed child why the sky keeps on to appear as blue during dusk, and if this is due to the Rayleigh scattering only, or due to other effects (like the Chappuis absorption). Sigh.

Maybe you have not yet had the time to consult the internet, so you chose to turn the child’s attention to other things, like poetry, for example. But stop.

All I am writing here is written from a layman’s perspective, and I am not going to suggest that I, myself, do understand it in other than layman’s terms. But we have to start from the beginning:

Why is the sky blue? Answer: the sunlight coming down from the sun to the earth gets scattered, and various wavelenghts of the visible light (various colors) get scattered in various ways. Result: the sky appears as being blue (it is the Rayleigh scattering, stupid).

But the Rayleight scattering alone is not enough to explain why the sky, during dusk, keeps on to appear as being blue. The theory would rather demand it to turn towards green and yellow, and grey. But there is something like the blue hour, and the theory does not seem to be complete or even correct. Problem: The blue hour is not yet explained.

Various physicists have contributed to explaining it more fully, and Edward Olson Hulburt was perhaps the one to have explained it almost completely (but, as it seems, not yet fully completely). And, in layman’s terms, the blue hour does appear as blue not only due to the Rayleight scattering (also, but not only), but also due to the Chappuis absorption. In simple words: some wavelenghts of the visible light get absorpted high above in the sky (in the so-called ionosphere) – and it is the ozone who acts here as a main protagonist, taking out some of the possible colorings –, with the sky at dusk appearing as remaining blue (and not green or yellow or grey). Brief: it is not due to the Rayleigh scattering alone, but also due to the Chappuis absorption which has to be included to an explanation of the blue hour (I am neglecting here to ask for the relative importance of each factor).

Now we may turn to poetry for a moment, but, as we know, Samuel Beckett yet had a longing for the romantic, but tended to suppress this longing, which may be the background of Beckett having his one protagonist Pozzo explain the twilight in this bizarre manner (and not necessarily as convincing as Edward Olson Hulburt could, by using the language of science (we come to that in the end). Pozzo is oscillating between the more prosaic and the more lyrical. And the performance Samuel Beckett wrote for Pozzo, in Waiting for Godot, reads as follows (in brackets are given the stage directions):

»POZZO:

(who hasn't listened). Ah yes! The night. (He raises his head.) But be a little more attentive, for pity's sake, otherwise we'll never get anywhere. (He looks at the sky.) Look! (All look at the sky except Lucky who is dozing off again. Pozzo jerks the rope.) Will you look at the sky, pig! (Lucky looks at the sky.) Good, that's enough. (They stop looking at the sky.) What is there so extraordinary about it? Qua sky. It is pale and luminous like any sky at this hour of the day. (Pause.) In these latitudes. (Pause.) When the weather is fine. (Lyrical.) An hour ago (he looks at his watch, prosaic) roughly (lyrical) after having poured forth even since (he hesitates, prosaic) say ten o’clock in the morning (lyrical) tirelessly torrents of red and white light it begins to lose its effulgence, to grow pale (gesture of the two hands lapsing by stages) pale, ever a little paler, a little paler until (dramatic pause, ample gesture of the two hands flung wide apart) pppfff! finished! it comes to rest. But – (hand raised in admonition) – but behind this veil of gentleness and peace, night is charging (vibrantly) and will burst upon us (snaps his fingers) pop! like that! (his inspiration leaves him) just when we least expect it. (Silence. Gloomily.) That's how it is on this bitch of an earth.«

After that performace a long silence is to follow.

Edward Olson Hulburt had already addressed the problem of explaining twilight before the Second World War (just as Samuel Beckett had mused about twilight). But Hulburt’s 1953 publication (see below) could take into consideration more data, and this also due to the collecting of data via rocket flights. These data had to be more convincingly explained. And this is, as far as I can understand it, what Hulburt did. At about the same time Beckett published his play. And one may look at these efforts from various sides here: from the viewpoint of history (the history of technology; but also the viewpoint of the history of postwar mentalities that express in Beckett’s play). Or from the viewpoint of someone who just examines various types of languages. More or less willing languages, more or less able to explain twilight (given that humans want to explain it). And this is why why I would like also to quote E. O. Hulburt, although I may not fully able to understand him (one may say maliciously here: just read it as a kind of poetry). The abstract of Hulburt’s first publication of the matter (published in 1938) reads as follows:

»Abstract

With a calibrated Macbeth illuminometer measurements were made of iz the brightness of the zenith sky and of ig the energy flux across a vertical plane from the twilight horizon for the depression Θ of the sun below the horizon from 0° to 13°. For clear sky conditions the iz, Θ; and ig, Θ; curves did not change within 30 percent with the season from October, 1937, to April, 1938, and were the same for evening and morning twilight. Calculation from the Rayleigh theory of molecular scattering and the observed iz and ig data showed that within ±30 percent the densities of the atmosphere from sea level to about 60 km were those of the density-height relation known to 20 km and extrapolated for a temperature of 218°K. It follows that the temperature of the twilight temperate zone atmosphere is 218°±15°K from 20 to 60 km. The influence of secondary scattering, determined from ig, although small for small values of Θ; increased rapidly with Θ; to such an extent that the twilight zenith sky brightness measures gave no indication of the distribution of density above about 60 km.«

[© 1938 Optical Society of America]

See further:

E. O. Hulburt, Explanation of the Brightness and Color of the Sky, Particularly the Twilight Sky, in: Journal of the Optical Society of America 43, No. 2, Februar 1953, p. 113–118

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS