M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Eying Glass  |

See also the episodes 1 to 11 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

And:

Eying Glass

(26.7.2021) ›It can be proven‹, Leonardo da Vinci says somewhere, ›that the sun is warm and not cold (as also has been

claimed‹).

I like this for its ›as also has been claimed‹. One may wonder, if Leonardo here refers to a serious debate or just to a

more or less serious discussion at dinner table. Was this a serious question, if the sun is warm or cold? It was. Is this

still a matter of debate? It is (see here). ›Warm or cold‹, they will ask you, ›compared to what?‹. But this

is not our question here.

What I am interested here is the kind of discussion at dinner table. Leonardo might have raised a glass of water, or

perhaps he stood up, raising a glass of water, eying the glass, and perhaps, as his pupils at dinner table must have

known (we don’t), he then started a longer monologue, lecturing them as regards the colours of the rainbow for example,

or as regards other topics. But perhaps Leonardo was only pedantic as far as artistic quality was concerned, less

systematic in his teaching, as he was less systematic in his notes. In this case he may have stood up, raising a glass of

water, eying the glass… But stop. Is this about the eternal question of ›rock crystal or glass?‹, my readers may wonder.

It is. Here comes the twelfth episode of our New Salvator Mundi History, but this is not only about an eternal question –

it is about a final word.

One) Some Postscripts

I’d like to think the field of Leonardo da Vinci scholarship as a kind of archipelago. There is a main island where

facilities for hero worshipping and infotainment are located (may this island be hit by a torrential rainstorm).

But there are also all kinds of other islands, some of which have never been touched by scholarship. Who thinks, for

example, to write on Leonardo as a maker of lamps? He did use large glass balls – pure glass was required which does

require so-called refining (›Läuterung‹) –, and he had these large glass balls, into which lights were meant to be

inserted, filled with water. This was meant to produce brighter light (see Ms. F 23v).

I am mentioning this as we enter the boat to the main island, but no, we will not set foot on the main island, we will

sail around it, to hit more interesting shores. And yes, I am thinking of myself as the local guide who will show you

some pearls.

But while we are heading to unexplored territories that have never been eyed by mainstream Leonardo scholars,

I’d like to add some postscripts to recent episodes of my New Salvator Mundi History.

As far as the Dominican cloister of Santa Maria delle Grazie is concerned, one should not forget to mention that its

prior, Vincenzo Bandello (uncle of Matteo, the novella author), had been active as an inquisitor. In Bologna, from 1490 to

1493. What exactly he did there, I don’t know. But this is the time in which witchcraft trials were put forward (that

were perhaps even being expected from inquisitors to be put forward).

Bandello seems to have been a man of the establishment, but also entangled into the debate about the dogma of the

Immaculate Conception. So actually a very interesting figure, whether we see him in The Last Supper (as Judas) or

not. Ludovico Sforza once had a debate between Bandello and an unknown Jewish scholar or religious authority staged.

Further we should mention that Leonardo referred to the model for ›the hand of Christ‹ (he is writing ›per la man‹ (sic))

as ›Alessandro Carissimo from Parma‹ – whatever this means.

And thirdly, as we are approaching the island of optics within the Leonardo archipelago, I’d like to draw the

attention to the pearls on the shoulder of the angel Leonardo is said to have contributed to Verrocchio‘s Baptism of

Christ (c. 1475 or even earlier). Don’t these pearls (or gems, or precious stones, I am just refering to these orbs as

pearls for convenience’s sake), don’t these pearls remind of and even anticipate the Salvator Mundi orb (picture above:

wga.hu)?

Two) The Island of Optics

Now we have reached the island of optics, but we will not make a tour around this island, because it is far too large.

We will set only set foot on one tiny shore which bears the name of ›Colours-of-the-Rainbow‹-shore.

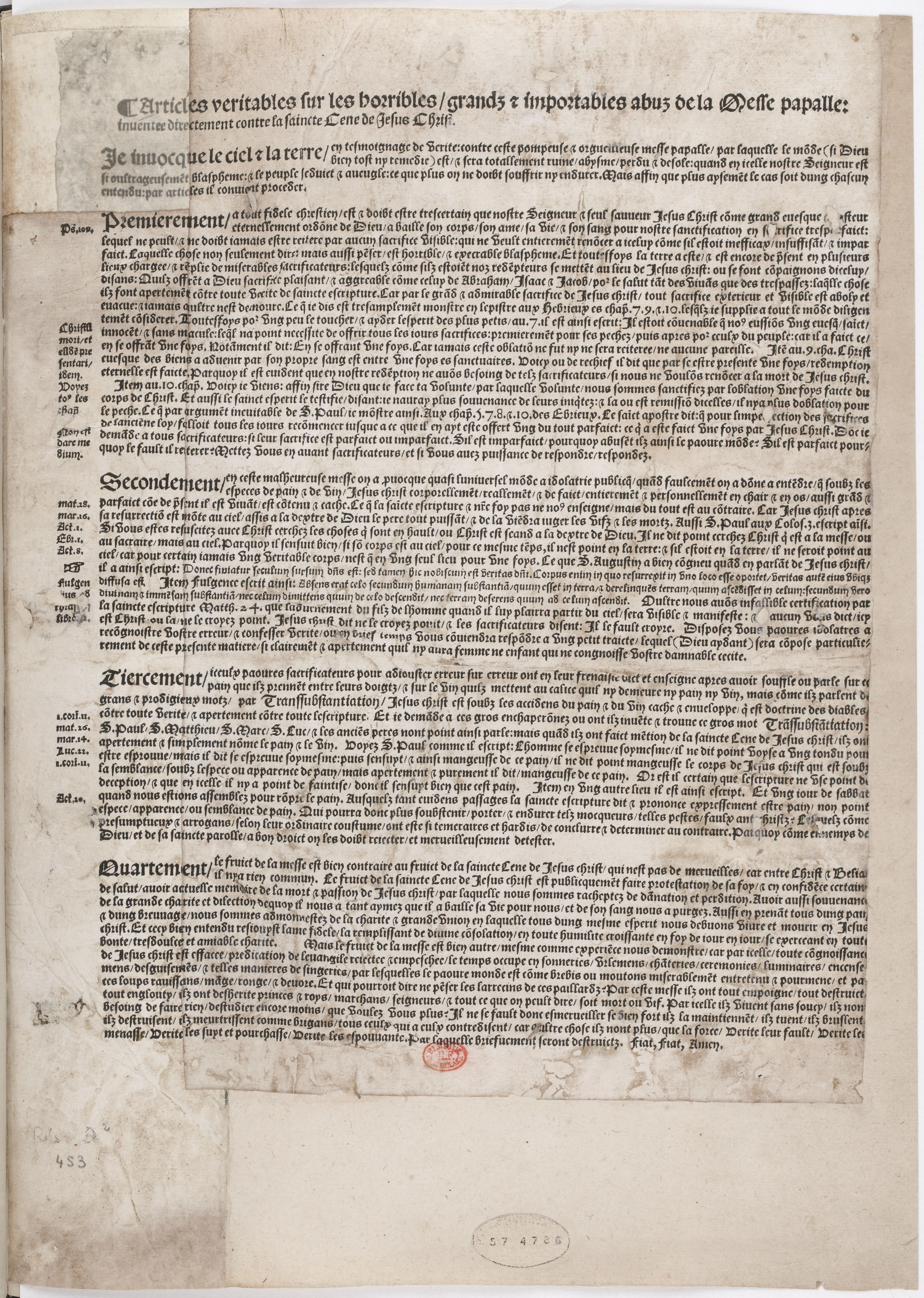

Leonardo da Vinci scholarship, no question, is a complicated field to navigate in. We will see that even the one Windsor

sheet this is about, is a complicated treasure map in itself. It was difficult to find images of the drawing that I want

to show, no, it was not only difficult: I had to produce them myself. And I am reproducing here images from Jean Paul

Richter (who edited Leonardo’s ›literary works‹ for the first time in 1883), from Pedretti’s commentary to Richter

(1977) and from the Kenneth Clark edition of the anatomical sheets from Windsor (second edition, provided with Pedretti’s

assistance). This does make sure that everyone knows that I am not making anything up here, and it does show, at the same

time, how Leonardo scholarship is being done, because these are the actual tools of Leonardo scholarship.

Let’s take a first look at the ›treasure map‹ (picture above: DS; Pedretti 1977); the drawing this is all about is in the

›field‹ on the left below in the picture above):

And now we are zooming in (picture below, also from Pedretti 1977). And what do we see (large picture is from Clark)?

We see an eye eying a glass of water. It looks like an eye eying a glass of mineral water with bubbles in it, but these

are bubbles in the glass. Because Leonardo is, while embarking on talking about the colours of the rainbow, referring to

these bubbles that are to be found in glass which is badly refined.

Leonardo uses a technical term, if he speaks of ›vetri mal purgati‹. The German language has preserved the religious

undertones, because in German the technical term is ›Läuterung‹. One would translate this as ›schlecht geläutert‹ (›badly

refined‹). Which means that there are still bubbles in the glass, which actually, by applying various methods, could be

eliminated – to get really pure glass (as required for the aforementioned lamps, for example).

As I am giving also the exerpt from Richter (1883) – Richter has the passage as paragraph 288 within his anthology –,

one can see that the English translation does not give the technical term ›badly refined‹, it just says ›coarse‹ (picture below).

If one wants to know the date or the approximate date of this sheet or of this passage, one has to consult Pedretti’s

commentary to Richter. The date given by Pedretti is c. 1508(-10).

Finally, while studying all this and above all, the text of this passage, we learn that Leonardo mused about the light

playing in these bubbles. And yes, this is about the natural sciences, but actually this is also about daily life. And

this is why I have said above that I am interested in these debates at the dinner table. Because Leonardo may have simply

raised a glass of water, eying the glass… And so on. And everybody may have listened or not.

Three) Conclusions

I have a whole number of conclusions to draw from all this:

1) First of all I have always found it a bit exaggerated to call Leonardo an ›expert for rock crystal‹.

Yes, he may have eyed rock crystal too (who doesn’t?), and he may have been seen as the expert for everything (but who

if not him?), but I would expect from scholarship to make sure that there is a balanced discussion. And this would mean that

we ask for Leonardo possibly being an expert for bubbles to be found in badly refinded glass too.

Since from all of the above we clearly see that Leonardo did not only work with rather large glass balls himself (as a

maker of lamps), that he did not only make a difference between pure and badly refined glass (he does know and uses the technical

term), but also that he muses about how the light plays in the bubbles to be found in badly refined glass, and on top of

all that: he makes a drawing of an eye (his eye?) eying bubbles to be found in badly refined glass, a drawing on a sheet

that Melzi did preserve (apart from the likely possibilty that all this was discussed at dinner table). If all this is

left away or brushed away, I would not call this a ›balanced discussion‹.

2) I think that all of the above makes crystal clear that there is a very large probability that the artist who painted

the orb of the Salvator Mundi is either Leonardo himself or someone very close to him, someone in his orbit; and I think

all of the above makes it also a possibility which is not at all far-fetched, that, again, Melzi might have been this

artist; Melzi supervised by Leonardo at Amboise in the main place; but since Melzi did preserve that sheet as well as his

personal memories of Leonardo, this could, theoretically also have happened much later; at any rate: I am not accepting

any longer that suggestive pseudo-argument of ›who else but Leonardo delved as deep into the natural sciences?‹ – because

we clearly see: such delving in may have included more or less serious discussions at dinner table, and the reading of

Leonardo’s notes;

3) The find of the above drawing (it could be referred to as a drawing on Windsor 19150r a; r means ›recto‹) does not

change of bit of my argument that is based on the linking of the Charlemagne orb in the Crucifixion of the Parlement of

Paris and the orb in the Salvator Mundi version Cook; what I am thinking (see also the Conques episode) I’d like

to sum up in the following way (and I am speaking of both orbs at the same time):

The average viewer might have seen a crystalline something, and perhaps also have understood the meaning of cosmos and

the meaning of a symbol of rule; the more educated viewer could even see a depiction of the Ptolemaic system in the orb,

with the crystalline sphere on the surface, with representions of stars on the surface; the technically informed viewer

could have mused if this crystalline something might have been inspired by glass or rock crystal (it certainly was

inspired by badly refined glass), but for the average viewer as for the more educated viewer at the time of the

Renaissance, the Biblical assonances probably were much more important; so it is actually a literally technical

discussion if the inspiration was rock crystal or badly refined glass, few people (Leonardo and Melzi among them) were

prepared enough for such discussions at all, so that it also makes sense that impure glass, in this case and despite its

actual ›impurity‹, could stand in for the crystalline sphere of heaven or for the jewels of Heavenly Jerusalem; badly

refined glass did stand in, and it did not matter at all, because no one (exept Leonardo and Melzi) were aware of that

anyway; the important thing – as to (art) history and as to my Salvator Mundi history respectively – is the fact the in

two places a crystalline something replaced a much more common globus cruciger, and that this did, as I am assuming, not

happen by chance.

4) Finally, after we have found that it is rather likely that in the thumb pentimento in version Cook the repertoire

of a workshop does show (and not the creative energy of genius), we see another argument that the Salvator Mundi version

Cook was created by Melzi and Leonardo, because with all of the above we have listened in into the conversations within

Leonardo’s orbit; the orb inclusions were underpainted and accentuated by light and shadow, as Dianne Modestini has

pointed out in her lecture on the Salvator Mundi; Leonardo speaks of daylight and the colors of the rainbow in the

passage given above, but he speaks of light playing in these bubbles, and whoever had painted these inclusions either had

looked, had eyed a glass of water (and thought while looking), or had listened to Leonardo talking while eying a glass of

water. This could also have happened in the workshop itself, and not necessarily at dinner table (picture below is taken

from Frank Zöllner's large-size Leonardo monograph; photo by me after Zöllner).

Selected literature:

See Dietrich Seybold, Leonardo da Vinci im Orient. Geschichte eines europäischen Mythos, Cologne 2010, for a list of

tools of Leonardo da Vinci scholarship (and see also my biography of Jean Paul Richter, which was published in 2014).

1495: At around this date Leonardo da Vinci is supposed to have begun The Last Supper. Giampietrino is documented as an active painter.

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

The 15 November 2017 inscribes into the chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie as well (pictures: youtube.com / Christie’s). Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers as well as the Salvator Mundi have their roots in the Milanese cloister. And there is something else: While the Salvator Mundi might mark the beginnings of serial production of paintings at the time of the Renaissance, Warhols work does practice and selfreferentially comment on serial production and on viral images (it had been a commission by an art dealer; see here). Does it also comment on the Salvator Mundi? How would Warhol have commented on the Salvator Mundi saga? Would he have created Sixty One Plus Salvator Mundi Versions? Perhaps he might have thought or said: why underestimating Leonardo? he did in fact invent the multiple. And perhaps Leonardo was even more furbo than anyone ever imagined – perhaps Leonardo did also invent and practice the selling of serial productions as (more or less unique) originals, each of every member of a series. Do we have a category for such objects, or do we still have to find one (even if just the Salvator Mundi version Cook might have been a gift and not a commercial product)?

See also the episodes 1 to 11 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS