M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM From Beginning to End |

See also the episodes 1 to 27 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

Learning to See in Spanish Milan

And:

From Beginning to End

(16.-17.10.2021) With this 28. episode of our New Salvator Mundi History I’d like to add a preface to my book.

This book – comprising 32 ›episodes‹ or ›chapters‹, of which two are ›reprints‹ of texts I had written earlier –

was written out of the momentum resulting from a first find: the crystalline orb that Charlemagne is holding, in

the Crucifixion of the Parlement of Paris. And this detail from a larger picture I have also chosen as a motif for

the title of my book.

The momentum that resulted from this initial discovery (result of browsing a popular book on the Louvre collections)

led me to build the new narrative; the narrative I have laid out in episode one to eight, and particularly in episode

one. In episode two I had laid my finger on the ›Melzi problem‹, one of the many blind spots of Leonardo scholarship.

A neglected problem that simply cannot be ignored, if one does not want to run into error in attribution. Other ›Melzi

episodes‹ continued that thread.

More finds did follow: the Hermitage Blessing Christ (episode nine), which is and will be important, no matter what

exactly it is, because it does show a significant combination of clues that cannot easily be explained (or dismissed); a

drawing by Leonardo of an eye ›eying‹ the bubbles in badly refined glass (which makes much obsolete what has been said

on ›rock crystal versus glass‹ concerning the Salvator Mundi orb. And in addition to that I have tried to clarify

the relation of the Salvator Mundi to other pictures that I consider to be reference pictures. New finds, also in

the area of Leonardeschi and Leonardo, I have presented in a number of episodes dedicated to such pictures (the Columbia

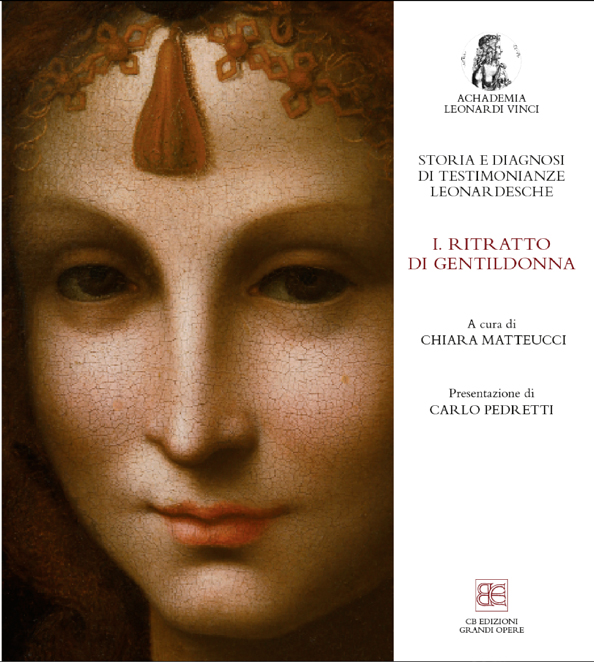

museum’s Portrait of a Noblewoman; the Louvre’s Vierge aux balances).

And while the book lays out a new narrative, a new history, I decided to work with an open structure, allowing me not

only to discuss related problems (such as ›Restoration today‹, which might sometimes be ›Digital Restoration‹), but also

things that make working on attributional problems worthwhile: I have discussed the flow of creativity around Leonardo,

concerning ›landscape‹, and I have related art history to musicology in two episodes developing a fresh view on the

Portrait of a Musician.

A key thread, however, is the thread of episodes dedicated to the Hermitage picture. Because the questions raised by

that picture would not even disappear, if it (I am considering this to be very unlikely) would be dismissed as a forgery.

The questions raised by this picture concern the thumb pentimento in the Salvator Mundi and its interpretation, but also

the general ›family tree‹ of Salvator Mundi pictures which are related to Leonardo or the Leonardeschi. I do consider the

pentimento interpretation of the proponents of an autograph attribution to be untenable, even if the Hermitage picture

had to be dismissed as irrelevant: because the alternative we see in the change of thumb positions Leonardo had already

thought through in the early 1480s. An interpretation that wants to see in this – rather trivial – change a clue as to

›creativity of a genius‹ is overburdening the pentimento with meaning. There is absolutely no basis for that, even if

one does – and I am doing that – consider Leonardo to be the author of the Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand. A crucial

episode lays out the ›History of Gestures‹ we see, in the bigger picture, as in Leonardo and the Leonardeschi.

I have further discussed topics such as the lack of a historical perspective on Leonardo studies, and also the reasons

why we see a crisis of discernment today. This book is not meant to solve all problems or to answer all questions. But

it lays out plausible answers to a number of questions. And in this episode, in this preface, I’d like to explain, again,

my methodological stance: I am thinking in hypotheses (because I do not want to repeat errors, committed so many times,

by prematurely suggesting certainties), but this does not mean at all that, what you can read here, would be wild

speculation. Not at all: Plausibility is the currency we are dealing with; plausibility versus implausibility is the

central dichotomy of scholarly thinking. What I am presenting here in my book, I consider to be carefully reflected

and – plausible. But I would never go as far as to suggesting that ›plausible‹ would mean: this is now the full truth.

Revisions might follow. Perhaps minor ones, perhaps major ones. But I am presenting a carefully designed structure of

observations and historical reconstructions. The logic of ›true or false‹ is decidely a too simple one. More on that

below.

(picture above and in title: detail from the Crucifixion of the Parlement of Paris; picture: Sailko)

One) A New Narrative Built On Three Crucial Finds

Martin Kemp had mused about the possibility that Leonardo da Vinci might have known the orb in Fernando Gallego’s

Christ as Salvator Mundi with the Symbols of the Evangelists in the Prado (picture above; date: c. 1492-94), but

had thought it to be very unlikely (see Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2019, p. 113 and p. 76ff.). Apparently Kemp did not know

the orb in the Crucifixion of the Parlement of Paris, because otherwise he would not have written (p. 115): »His

[Leonardo’s] rather literal replication of the optics of a crystal sphere appears to be uniquely his.«

It seems clear now that it was not. The Paris orb is a rather literal replication of the optics of a crystal sphere

as well. And having mused about the same question, namely if Leonardo might have known it, we also had come to the

conclusion that this might be rather unlikely, too, but: this picture is placed in too prominent a place as to ignore.

As having been placed in the room where the French king was meant to sit in the Parlement of Paris, the High Court, this

orb is to be named as an orb placed at the very heart of French politics. Three kings, during Leonardo’s lifetime, might

have, must have known it. And hence we also had raised the question of who of these three French kings might have

had the most ardent imperial ambition, an ambition literally mirroring what Charlemagne, who is holding this orb, is

symbolizing: being the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. And the answer to that question is: Francis I. Since for the

Empire’s crown, due to a vacancy, only Francis I was most seriously and most passionately striving – in 1516-1519, which

is also exactly the period of time Leonardo da Vinci has spent in France.

No, Leonardo da Vinci, probably did not know this orb, but he was in most intense contact with the court of Francis I in

1516-19, with artists, with the king’s family, and particularly with the king’s mother, Louise of Savoy, who also had

been the person who had wanted Leonardo in France. Who was his, and Melzi’s and Salaì’s actual host. She, most certainly,

also knew the Paris orb (she had acted as regent, while Francis I was away, fighting in Marignano, in 1515), and she

also can be quoted as someone knowing that the Empire was something that Christ was holding in his hands, and she is

transmitted to have said that, after the campaign of her son for the crown of the Empire had failed in 1519. All this

made us conclude that it is plausible to say that the Salvator Mundi orb was meant to correspond with the Paris orb,

and that it is plausible to say that it was painted in 1516-1519, and that it is plausible to say, also due to stylistic

observations and comparisons, that the Salvator Mundi is a Melzi-Leonardo-Salaì hybrid, painted or perhaps

better: produced for the French monarchy in around 1516-1519.

The question, by the way, if other Salvator Mundi versions, with comparable orbs, also do correspond with the imperial

ambitions of French Kings, has to be raised as well, namely, for the Naples version, for example, but also for the

Yarborough version and other ones. The find of the Paris orb was the first of three finds that all have many

implications, but above all: the first of three finds upon which a new narrative can be built. A new narrative as to the

most prominent version, the version Cook, but also as to the history of all the other versions.

A second crucial find allowed us to say that other candidates for the authorship of version Cook can be ruled out, namely

Benardino Luini and Cesare da Sesto. Leonardo da Vinci has transmitted a drawing of (his) eye, eying the optics of badly

refined glass, which means, the bubbles within badly refined glass, and how the light might play in these bubbles. It

would be rather absurd to ignore this find, this drawing (obviously unknown to all leading Leonardo specialists), which

makes more or less obsolete all that has been said as to the question of ›rock crystal versus glass‹. This find limits,

as I have said, possible authorship of version Cook to the most intimate circle, to which Luini and Cesare da Sesto did

not belong. In fact we have no clues at all that whould indicate that these two artists interacted with Leonardo directly

at all, and we don’t see either any specific similarities in style (what has been named, cannot be called specific, and it

would be very naive to build anything in connoisseurship on very general similarities only).

Rock crystal corresponds with special occasions – it is exceptional, one does not see rock crystal on a daily basis – but

badly refined glass does not, a glass of water is as common as a daily meal, and hence I have said that I would not

longer accept the argument that only Leonardo could have painted the Salvator Mundi, because only Leonardo delved as

deep into the sciences. No, we have to refute that: everyone in Leonardo’s most inner circle might have known about what

Leonardo had said as to the colours of the rainbow, being seen in or around bubbles within badly refined glass. And I am

considering, as I have said, my find, the drawing of an eye that is eying badly refined glass, as a proof that version

Cook either must be coming from Leonardo’s or Melzi’s workshop. And, without any doubt and frankly, this is a better

proof that anything we have heard in the past ten years. But a proof as to autograph authorship it is not. Not at all.

Because, on a level of painterly technique, any Sunday-painter, if being supervised by Leonardo, could produce such orb,

and most certainly Francesco Melzi, and also Salaì, if being supervised by Leonardo, could have produced such orb.

The third (chronologically actually the second) crucial find was the picture of a Blessing Christ in the

Hermitage. This picture, literally, raises so many questions that I have to deal with these questions separately in the

following separate paragraph.

Two) Further Reflections on a Blessing Christ

After the October Revolution in 1917 many paintings from Russian private collections were being seized. The new regime

partly sold such pictures (to the West), and partly stored them, also retributing them to museums like the Hermitage (St.

Petersburg) and the Pushkin Museum (Moscow). This history is complicated and also the reason, probably, that we,

currently, have no actual provenance for the Hermitage Blessing Christ. All we know is that it is said to have entered the

Hermitage in 1931, and that it was coming from the Pushkin Museum. And, finally, that, somehow, this process of transfer

was handled by »Antikvariat All-Union Association«, which was the organization that handled the selling and retributing.

If, yet, we had an actual provenance, we perhaps would be able to rule out some options as to this painting. But so far

we only know that the picture is important, no matter what it is exactly, and that, with this pictures, also the shadows

of Lenin and Stalin enter Salvator Mundi history. We can assume that this picture of the Hermitage, before the

Revolution, was in a private collection. But we do not know, at present, which one it was, and what history the picture

might have had.

The Hermitage Blessing Christ is important, no matter what it is. Which means: no matter who the author of this

crucial picture is. Why is it crucial, no matter what it is? Because it shows, and we can see a very specific combination

of clues. It is not about single clues alone, it is about the combination, and the very fact that we see this combination

has to be explained. What clues do we see in combination? We see an inscription with a date (1495), we see the

Leonardesque blessing hand, but shown with the thumb stretched (and not bent), we see a cloak, partly covering a

crossed stole, we see a (rather convincingly done) piercing gaze, and we see a general design which is that of the

Leonardesque Salvator Mundi family. We further see curly hair with lustre, a dark background and an ornamented garment

hem (with the hair, very deliberately, set against this ornament). An orb, finally, we do not see.

To those hoping that this picture might disappear again I can say right now: this picture is also important if it would

turn out to be a forgery, because the combination of clues it is showing is so speficic that it has to be explained why

we see this combination of clues here; secondly, it is rather unlikely that this picture turns out to be a forgery,

because it is rather unlikely that someone, for example in the 19th century, was able, willing or even motivated, to

combine these specific clues; thirdly: the option that this picture might be a forgery might be ruled out, as soon as we

know more about its provenance, and fourthly (last but certainly not least): the questions raised by this picture will

remain anyway, as to the notorious pentimento in version Cook and as to the family tree of Salvator Mundi pictures, and

even if the Hermitage picture would disappear again, these questions stick to and are raised by other pictures,

pictures from Leonardo’s circle, but also by Leonardo’s own pictures, namely the very early Adoration of the Kings,

and the rather early Virgin of the Rocks (as shown in the episode dedicated to a History of Gestures).

I have not claimed to know exactly what this pictures is and by whom it is (neglecting the possibility that it might also

be a faithful copy of an old picture), but I have proposed a working hypothesis. In addition to that, I can say that we

have to consider the mysterious Spaniard that was close to Leonardo in 1494 and 1495, and whose name was ›Ferando‹ or

›Ferrando‹ (Calvi 1925, p. 154). It this Spaniard, who might have worked in the Castello Sforzesco, was Hernando Llanos,

we might discuss, if ›L.S.‹ might be an abbreviation for Llanos. As well as we have to discuss a letter by the duke.

Because Ludovico Sforza was sending a letter to the prior of Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1497 (published in 1874 in the Archivio Storico

Lombardo), naming the embellishments, including paintings, he had envisioned for the convent and church. And apart from

all that we have to consider the possibility that cartoons might have been passed from one Valencia artist to the other.

And in that city, in the first half of the 16th century, we see dynasties of painters: Paolo de San Leocadio (my working

hypothesis as being the author, with L.S. being read as ›Leocadio Santo‹) had a painter son. And Juan de Juanes, whose

father had already been a painter, had a painter son as well. Juan, as someone, who directly is quoting from The Last

Supper (see his Last Supper in the Prado), had been trained in Italy, as earlier scholarship had been assuming. New

scholarship has dismissed this idea, assuming that Valencia painters might have been influenced by Italian pictures.

Also by cartoons that, possibly, passed from one generation to the next?

Finally we have to consider the possibility that duke Ludovico Sforza had commissioned other painters than Leonardo

to do paintings for Santa Maria delle Grazie. We hear of a Battista degli Alberti di Abbiate, for example, who was in

touch with Leonardo, and who worked in the sacristy. We have to consider the possibility that Leonardo might have

assisted his collegues with ideas, and that, if not him, someone else might have realized his ideas. For Santa Maria

delle Grazie.

Three) Revisions Resulting from the Process and Further Research Paths

While writing this book a have revised my opinion concerning the relation of the Salvator Mundi and the Columbia

museum’s Portrait of a Noblewoman. And I have come to accept – or to include – the idea that Salaì may have

contributed more to the Salvator Mundi than I had thought earlier. I am considering this idea now more decidely,

still regarding, as earlier, the picture to be a Melzi-Leonardo-Salaì-hybrid (initially I had mused about the idea, if,

at Amboise, Melzi and Leonardo might have reworked a Salaì Christ, and if, Salaì may have contributed, helping to

finish the picture, the folds).

But I have slightly adjusted my view due to a new find: the Christ with Crown of Thorns that had passed as by a

›Follower of Luini‹ – I am considering to be another picture by Salaì. And I am considering the following scenario:

Since Dianne Modestini has considered the curls in the Salvator Mundi to be one of last elements that had been added

to the picture, it might be that, after Leonardo had died, Melzi and Salaì saw themselves confronted with the question if

and how this picture, being still unfinished, should be finished. And Salaì may have added the curls, since in the

Christ with Crown of Thorns we see, on the left side of the picture, hair that I have referred to as ›vintage

Salvator Mundi hair‹.

This, of course, is a hypothetical scenario and various alternatives exist, but it would explain what we see (and we are

seeing not just single pictures, but a network of reference pictures, at least, if we want to see them). The idea

that Leonardo contributed to the Christ with Crown of Thorns I do consider as being not very likely – why doing

masses of hair at all, as Salaì seemed to like, if this was the one thing he could not do alone?).

The Columbia portrait I am still seeing, as I always have been, in a very close relation to the Salvator Mundi, but I

am considering now this relation to be more complex: the two designs are closely interrelated, because, as I am

supposing, Leonardo was into the exploration of the most direct gaze, inquisitory or unfathomable, and into the

exploration of portraiture based on the idea of alluding to inner movement vs. the idea of avoiding any allusion to inner

movement (which has a face appearing like a mask). If I am right in assuming that the face of the Columbia portrait was

done by Leonardo, and that the blessing hand of the Salvator Mundi is by Leonardo as well, parts of both picture are

by the same hand, while the design of both was thought out by the same brain. As to the rest of both pictures I am

assuming that, on the one hand, Melzi and Salaì were responsible for the main part of the Salvator, while the

Columbia portrait was finished by an unidentified hand (the hand of an assistant of Lorenzo di Credi, for example, or of

young Giampietrino or of Salaì, or, if the picture was finished only much later, of Melzi. But the two pictures served

very distinct purposes: the Columbia picture, perhaps left unfinished after Beatrice d’Este had died in 1497, or after

the downfall of the Sforza, Leonardo might have used for study and for instruction of pupils (it was repeated in another

version, now in Russia, displayed in the Hermitage). While the Salvator Mundi, in my opinion, has nothing of that,

and was – on some level and paradoxically – a very routinely produced picture, but being produced under very

extraordinary circumstances – as the last, or one of the last picture Leonardo contributed to at all.

Several research paths have to be indicated here, paths that might or should be followed. And one of the paths concerns

walnut:

Walnut has also, like the pentimento, overburded with meaning. Leonardo does recommend walnut, yes, but he does not

recommend it in the first place (he names cypress). Not second (pear), not third (service-tree). It comes fourth, and it

is the last kind of wood, actually, that Leonardo names for the making of panels to be painted upon (see Richter, § 628).

Not every picture having been painted on walnut, hence, should, at least not immediately, be seen as a picture

potentially having been painted by Leonardo (the Christ with Crown of Thorns is on walnut as well, to give an

example).

And dendrochronology, as a method to establish rough dating, can be applied to walnut as well. Because also this field is

in development. Walnut can be tested, but it is required that the supposed region also has oaks (to calibrate), because

clusters of walnut trees are rare, and references hence are lacking. But specialists have thought about solving the

problem, only the idea is not yet widespread (the consensus that walnut cannot be tested, was once the consensus of

scholarship). But still one might assume that also this field is in rapid development and will further develop – so that

also paitings on walnut panels could once, potentially, and if this is wanted, be tested.

A further research path concerns ›Naples‹:

The Naples Salvator Mundi version’s history has been a Naples related history from very early. And the only painter

that we see depart from Leonardo’s orbit to Naples is Protasio Crivelli, student of Marco d’Oggiono, while Francesco

Galli had been coming from Naples, initially, to enter Leonardo’s orbit in Milan. Thus it would be possible to consider

the authorship of Crivelli for the Naples version, which Dianne Modestini sees as having been done rather in parallel to

version Cook, as well as having been finished earlier. But if cartoons did exist, potentially even were being multiplied

and spread, he have to consider the possibility that the picture is much more complex. It is also possible that, on the

basis of cartoons, pictures are being realized only much later and somewhere else, and that, seeming connections, obvious

similarities, are not to be explained by direct causality, but by very indirect ones. The picture, decidedly, has to be

broaded. And has to include also a Melzi orbit.

And this is perhaps the most important future research path: we have to think about a Melzi group, after having

identified and established a Marco group (with the significant globe), a Boltraffio group, a Giampietrino group, and now

a Salaì group having been initiated – while a Melzi group, i.e. a group of Salvator Mundi versions that could or can be

associated with Francesco Melzi is still lacking. But is it very likely that such Melzi group would be lacking? We have

pictures that, potentially, could belong to such group: the Yarborough version, also version Cook, of course, but also

Ganay could be a candidate. Further revisions of the sketchy Salvator Mundi family tree are likely, further entrances as

well. But further reflections on how exactly to group these pictures, how to see their relations, wanting.

Four) What Do You Expect?

How might the Salvator Mundi saga actually have begun? And how might it end?

On a level of history I would say that it is likely that even Leonardo da Vinci, as an artist, must have had some things

in petto: routine things, that, from painters of altarpieces, were required to deliver. Such as the addition of a God the

Father on top of a retable, for example.

Since on top of the altarpiece with the Virgin of the Rocks panel a God the Father was meant to be placed, I

would suggest that, here, we have at least a symbolical date for the Salvator Mundi saga to have started. A search

for and a study of God the Father figures on such altarpieces in Lombardy shows that the basic composition is very

similar: God the Father is holding an orb, respectively a globus cruciger, as well as giving a blessing. Perhaps it is

also no coincidence that, after Leonardo had died, a Christ in the manner of God the Father was among Salaì’s

possessions, and that, on another list, this very picture was named God the Father again. Santa Maria delle Grazie I

am considering to be the key location where the Salvator Mundi design is very likely to have had existed, even

if Leonardo never actually realized a lunette with such motive in the convent (we may simply assume that, in his working

space, in the convent, or in the Castello Sforzesco, such design could be seen, a cartoon, as already Maria Teresa Fiorio

had assumed, in the Raccolta Vinciana, in 2005). It is all the more likely since the duke, Ludovica Sforza, was

commited to an embellishment of the convent, and as sources show, he was very comitted. Artists must have had things in

petto.

Occasionally it has been said that the Salvator Mundi saga is only going to end, if a decisive proof will be found,

indicating that the Salvator Mundi is either by Leonardo or not. If only things were that simple (and in a world of

hybrids they are not).

I am suspecting that many people do have an interest in the saga to continue. This might not apply to all people, but the

expectation to find a ›smoking gun‹, potentially deciding the question, is, in my opinion, rather too high. We rarely

have such proofs; what we are dealing with are probabilities, plausibilities (hopefully beating implausibilities, but not

even this is sure). And I tend to say that the expectation of ›either-or‹ is a simplified logic, a logic understood in

the sphere of the big audience, but it is not necessarily the only logic, and usually not the logic scholars have to deal

with on a day-to-day basis. Because things are not that simple. The logic of the wordly farce is not the logic of

scholars, at least it should not be, and the saga will probably never end with such big bang of a final proof or word.

But we have decidedly more that incertainties: we have plausibilities, and I have developed a solution of the Salvator

Mundi puzzle that I consider to be plausible, a solution that takes into account every kind of evidence, and a solution

that postulates that the picture is a hybrid, and, generally, that things are not that simple. Will it be heard?

Five) What Do I Expect?

I rather know what I am not expecting, than what I am expecting or should be expecting:

I do not expect those who have deliberately been ignoring my work, to now appreciate or to approve it.

I do not expect those liking to watch the money, the scandal, the buffoonerie, the clash of egos, suddenly turning to

like something more seriously reflected and earnest.

I do not expect readers still wanting to live in the Gutenberg Galaxis only, to turn to attempts of re-inventing the book

in the age of digitalization (even if this book, deliberately, has not been written for being read on the smartphone).

I don not expect such readers even to recognize this book as a book (which it is: a new kind of book, built out of a

thread of 32 chapters, ›streamed‹, if one likes to say so, while being written, also showing a path of thinking, with this

episode or chapter 28 being the preface; because such structure, being made of text and images, works like a book, can be

read as a book, and could also be unfolded materially, if turned into a PDF and printed).

I do expect perhaps to enjoy a little that I have found a structure that, in several ways, sums up, in a kind of

synthesis, what I have been doing now for many years, combining the study of art and history.

I do further expect to further enjoy the intellectual adventure that I have been committed to for many years now, which

is study, contemplation, but also, yes, intellectual adventure for the sake of intellectual adventure.

I do further expect from scholarship that truth does matter (as an ideal), and that intellectual honesty does matter, as

well as plausibility, being though to beat implausibility, which, if having been identified as such, has to be questioned

and, possibly, dismissed. Because, otherwise, the idea of scholarship as such had to be dismissed. And also the idea of

thruth.

I am sure, finally, that I have found, with the music of the Renaissance, something that serves as an escape route from

many things (in case I should be needing one) and I am sure that I am going to further enjoy the study of the music of

the Renaissance.

And I am sure to turn to new and other things now, while still having an eye on several Renaissance related research

paths and fields, and while still contributing, every now and then, to these fields, if, still, I should have further things to say.

This Salvator Mundi project has delayed other projects, and I am going to be committed to these projects now (more or

less exclusively).

The Bottega of Leonardo da Vinci

The picture of the bottega of Leonardo da Vinci is not as blurred as one might imagine (for details see Seidlitz 1935, p. 530; Marani 1998). We will focus here on the early and middle years (up to 1512), and not on the late years, and one might begin with saying that with Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono we see two figures enter the orbit of Leonardo at the beginning of the 1490s that we believe to know rather well. We also see Salaì enter the orbit, at a very young age, and we have, in addition to that, a couple of names, names of figures that we do not seem to know very well, or not at all (a Giacomo, Giulio Tedesco, Galeazzo). Last but not least we have the Giampietrino problem: Giampietrino enters the scenery, but it is a matter of controversy (as far as this question is debated at all), when, since also Giampietrino is still very young.

It is noteworthy that Marco d’Oggiono, already at the end of the 1480s, seems to have had an own apprentice, and that Marco and Boltraffio did create the Pala Grifi together (a picture today in Berlin; picture above), even before Leonardo began to work at The Last Supper in 1495. Due to the work of Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi we today do know more about Francesco Galli, also called Francesco Napoletano, who did die in Venice as early as 1501. One might imagine that Galli went to Venice with Leonardo in 1501, and if Galli, during the 1490s, for example might have cooperated with Marco, we would have found an interesting perspective: since, if only one single picture of the Marco group would be associated with Francesco Galli/Francesco Napoletano, we would have a picture with hand option 2, a picture that must have been created before Galli died in 1501. Which would mean that hand option 2 must have existed early, and my theory of the pentimento in version Cook as a mere switching from (preexisting) option 1 to (preexisting) option 2 would be positively proven as well as the theory of the pentimento supposedly showing the creative energy of genius (changing his mind) would be definitively falsified.

Brief: in the 1490s Leonardo mentions once that he had paid ›two masters‹ (probably Marco and Boltraffio) for two years; and once that he had six bocche to feed (probably again Marco, Boltraffio, plus Salaì and some of the unknowns).

Below a rather early Marco picture (according to Janice Shell), the Young Christ Blessing of the Galleria Borghese:

And here is a picture (not the only known picture) by Protasio Crivelli, formerly the apprentice of Marco d’Oggiono (picture by Sailko; the date appears to be 1498; location: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte):

In 1501 (3.4.) Pietro da Novellara informs Isabella d’Este that Leonardo seems to live ›from day to day‹ (see Marani 1998, p. 14). And he has seen Leonardo intervening from time to time in portraits done by two of his garzoni (»fano retrati«). But who are these, and which portraits are these (if this would have been about a Isabella d’Este portrait, Pietro would have noted; and after the Sforza had been expelled, portraits of court ladies and courtiers made no sense)? After having written on the picture of a young woman in the Columbia Museum of Art in one of the last episodes, I would now suggest the following:

Leonardo might have done a portrait of a Sforza court lady in the early Milanese years (and still in the Florentine portrait style), a portrait in terms of a drawing or a cartoon. He might have begun also a painting, but since the Sforza court got expelled and exiled after the French invasion, he might not have finished such portrait. He might instead have used it for the instruction of his garzoni: the Columbia picture might have been the one begun by Leonardo (as he seems to have begun portraits with the face, as later in the Mona Lisa), a picture that he might have had a pupil finish, with him retouching it again, adding some lustre. The picture in a private Russian collection might be a second version that he had a pupil repeat (after the first version and the drawing, respectively the cartoon). The Columbia picture shows much gusto for the grotesque, the second version less so, but still to some degree. Thus we would see pictures that have their origins in the first Milanese period (and even in the early Florentine period), but were actually done later (after 1500). And Leonardo might have had a hand in the Columbia picture whose head with the hair as well as the ornated hair net superbly being modelled into the dark is of exquisite quality (as also a single one pearl is, while other pearls are rather mediocre as also the bust and the modelling of the dress is). We see, as I have attempted to show in episode 13, two pictures that fit into the context of Leonardo’s thinking and doing rather than into the context of Boltraffio’s autonomous work:

In 1504 a Jacopo Tedesco, in 1505 a Lorenzo (di Marcho) enter the orbit of Leonardo.

In around 1505 Fernando Yáñez enters the orbit of Leonardo, helping him with the Battle of Anghiari (as also does Riccio della Porta). Yáñez cannot be the author of the Prado Mona Lisa, if the Louvre Mona Lisa was finished only years later, since the dates (showing that Yáñez was active in Spain after 1506) do not allow to postulate it. In works of Yáñez done in Spain, however, we find echoes of Leonardo’s works (see the example below).

Around 1507 Francesco Melzi becomes a pupil of Leonardo (and also a sort of secretary).

In 1511 (or even earlier) Giampietrino is an autonomous master.

In 1511 Salaì seems to have created a (signed and dated) picture of Christ:

In around 1511 we see Marco, Boltraffio, Giampietrino and – Giovanni Agostino da Lodi in close contact, not only because we have a source indicating exactly that – we also have pictures indicating exactly that, and one of these pictures seems to be even dated (but the ›date‹ – ›XII‹ – is rather referring to the ›age of Christ‹):

The Prado Mona Lisa (below) was probably begun at the time Leonardo also started reworking or completing the Louvre Mona Lisa, probably due to Giuliano de’ Medici wishing so, and hence perhaps in around 1511/12.

In around 1517 Marco d’Oggiono is cooperating with Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (see Shell, p. 173).

***

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

I am dedicating this book to my favourite Youtube-clip: Vox Luminis interpreting Susanne, un jour, by Orlande de Lassus; because this is the most outstanding clip I have seen since long; since it is Renaissance music, providing an escape route from many things (if necessary); because it shows what five voices can do (in a chilly church interior); because the mix of casual style and professionality is charming, as is the body language of all of them (with the soprano, elegantly, playing hide and seek behind the microphone pole. All in all: it is breathtaking. Unbelievably beautiful and breathtaking.

See also the episodes 1 to 27 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

Learning to See in Spanish Milan

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS