M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM  Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument A documentation |

There are two reasons why I am getting suspicious whenever I am hearing the ›left-handing hatchings argument‹ brought forward as to the attribution of drawings to Leonardo da Vinci. For one: hatchings that begin (or seem to begin) at a contour and are (or seem to be) directed from that ›south east‹ starting point at the contour towards ›north west‹ are such an obvious ›signature property‹ for a left-handed (or ambidextrous) artist that the ›signature property‹ cannot be taken as such anymore (or only with the greatest caution and combined with into-depth studies of followers’, copyists’ and forgers’ drawing styles): because anyone, to the last epigone, pasticheur and copyist (if not to mention forger and faker) is also aware of that obvious property.

For two: as a right-handed person, interested also in drawing, I am aware how easy it is to produce these kind of hatchings with my right hand, and this in even various ways (one of which might simply be to turn a sheet upside down).

Said this I believe that it is about the time to review the history of this ›left-handed hatchings argument‹ and to put together a documentation of uses of that argument, a documentation that hopefully may inspire a general thinking as to this supposed ›signature property‹, as to ›obvious signature properties‹ (and their use in attributional studies) in general and last but not least: as to the possible danger of ›self-fulfilling-prophecy‹.

|

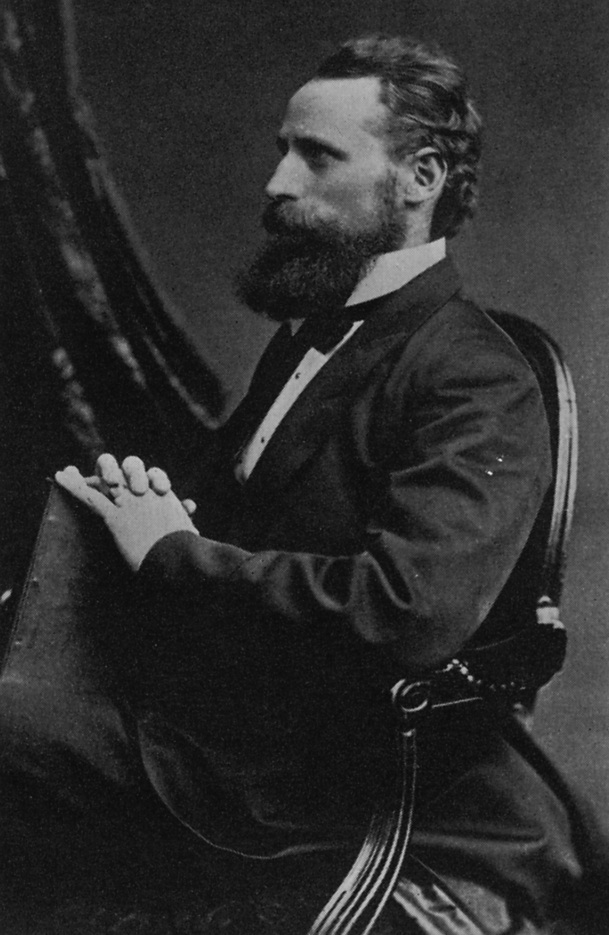

| To set the scene there is no better way than to listen into the conversation between Giovanni Morelli and his pupil Jean Paul Richter in 1879 and 1880. This leads us into the very early days of Leonardo da Vinci-drawings’ connoisseurship (very few drawings, actually, were known at all, at these early days, to the general public). And what is striking in listening into that conversation is, once more, Morelli’s guiding hand but also cautiousness and scepticism on the one hand, and Richter’s enthusiasm on the other, an enthusiasm, in the beginning also sceptical, to have found, or seemingly have found, something to work with that seemingly did/does simplify things: the one exclusive property, supposedly found within one class of works (that by Leonardo) only, and not, or apparently not, or less in works of others. And Morelli, at some point, did stop to flag his scepticism (subsequently marked in yellow letters), the question yet remaining, and remaining up to the present day: ›how reliable is that?‹ Or: ›how illusionary, respectively misleading?‹. |

Giovanni Morelli (October 22, 1879): »Ich entsinne mich nicht mehr, ob Lomazzo oder ein anderer Schriftsteller des 16. Jahrhunderts es erzählt, dass nämlich Leonardo mancino gewesen sei, d.h. dass er sich mehr der linken als der rechten Hand bedient habe. Als ich diese Bemerkung las, lief ich sogleich in die Ambrosiana, um mir dort den »Codex Atlanticus« durchzusehen; darin kommen ja viele Federzeichnungen vor; und in der Tat hatte ich die Freude, jene Bemerkung an allen Zeichnungen im Codex bestätigt zu finden. In der nämlichen Absicht besah ich mir sodann das kleine Skizzenbüchlein Leonardos in der Bibliothek Trivulzio, und auch da fand ich überall dieselbe Strichlage, und diese Tatsache fand ich in den drei echten Handzeichnungen Leonardos, die die Albertina, und in den drei weiteren echten Zeichnungen Leonardos, die die Esterhazy-Sammlung zu Pest besitzt, ebenso in den echten Zeichnungen Leonardos der Uffiziensammlung, jener von Turin usw. Die Striche auf den echten Zeichnungen Leonardos gehen nämlich alle von links nach rechts und von oben nach unten; wo es aber die Form erheischt, gehen die Striche geradeaus, also so: \\\ und =, aber nie, wenigstens in kleinen Zeichnungen nicht, ///, wie die meisten anderen Künstler zeichnen. Damit will ich freilich nicht sagen, dass es nicht auch etwelche Zeichnungen von Leonardo da Vinci geben könne, deren Striche auch von rechts nach links gehen, glaube aber doch vorderhand feststellen zu dürfen, dass die meisten echten Handzeichnungen in kleinem Format des Leonardo (die, wie sich dies von selbst versteht, auch die anderen Requisiten der Echtheit in sich vereinigen) die oben bezeichnete Strichlage von links nach rechts aufweisen. An Ihnen [ist es] nun, mein Freund [Jean Paul Richter], diese meine Bemerkung entweder zu bestätigen oder aber als unbegründet nachzuweisen.« Giovanni Morelli (October 22, 1879): »Ich entsinne mich nicht mehr, ob Lomazzo oder ein anderer Schriftsteller des 16. Jahrhunderts es erzählt, dass nämlich Leonardo mancino gewesen sei, d.h. dass er sich mehr der linken als der rechten Hand bedient habe. Als ich diese Bemerkung las, lief ich sogleich in die Ambrosiana, um mir dort den »Codex Atlanticus« durchzusehen; darin kommen ja viele Federzeichnungen vor; und in der Tat hatte ich die Freude, jene Bemerkung an allen Zeichnungen im Codex bestätigt zu finden. In der nämlichen Absicht besah ich mir sodann das kleine Skizzenbüchlein Leonardos in der Bibliothek Trivulzio, und auch da fand ich überall dieselbe Strichlage, und diese Tatsache fand ich in den drei echten Handzeichnungen Leonardos, die die Albertina, und in den drei weiteren echten Zeichnungen Leonardos, die die Esterhazy-Sammlung zu Pest besitzt, ebenso in den echten Zeichnungen Leonardos der Uffiziensammlung, jener von Turin usw. Die Striche auf den echten Zeichnungen Leonardos gehen nämlich alle von links nach rechts und von oben nach unten; wo es aber die Form erheischt, gehen die Striche geradeaus, also so: \\\ und =, aber nie, wenigstens in kleinen Zeichnungen nicht, ///, wie die meisten anderen Künstler zeichnen. Damit will ich freilich nicht sagen, dass es nicht auch etwelche Zeichnungen von Leonardo da Vinci geben könne, deren Striche auch von rechts nach links gehen, glaube aber doch vorderhand feststellen zu dürfen, dass die meisten echten Handzeichnungen in kleinem Format des Leonardo (die, wie sich dies von selbst versteht, auch die anderen Requisiten der Echtheit in sich vereinigen) die oben bezeichnete Strichlage von links nach rechts aufweisen. An Ihnen [ist es] nun, mein Freund [Jean Paul Richter], diese meine Bemerkung entweder zu bestätigen oder aber als unbegründet nachzuweisen.« |

Jean Paul Richter (November 3, 1879): »Die Aufklärung über »Leonardo mancino« fand ich bei Luca Pacioli. Sie gibt gewiss die plausibelste Erklärung.« Jean Paul Richter (November 3, 1879): »Die Aufklärung über »Leonardo mancino« fand ich bei Luca Pacioli. Sie gibt gewiss die plausibelste Erklärung.« |

Jean Paul Richter (March 12, 1880): »Ich brenne darauf, in Windsor darüber mir klarzuwerden, ob auch solche Blätter von Handzeichnungen, welche mit Beischriften in Autographen versehen sind, immer so: \\\ schattiert sind. – Nach dem, was ich letzthin in Photographien der Grosvenorpublikation sah, scheint mir das zweifelhaft zu sein.« Jean Paul Richter (March 12, 1880): »Ich brenne darauf, in Windsor darüber mir klarzuwerden, ob auch solche Blätter von Handzeichnungen, welche mit Beischriften in Autographen versehen sind, immer so: \\\ schattiert sind. – Nach dem, was ich letzthin in Photographien der Grosvenorpublikation sah, scheint mir das zweifelhaft zu sein.« |

Giovanni Morelli (March 30, 1880): »Mein lieber Freund, Sie haben da eine wahrhaft Ihrer würdige Beschäftigung gefunden, und ich verspreche mir, dass Sie die noch dunkle Frage meisterhaft lösen werden. Ich rate Ihnen, vorderhand noch sehr vorsichtig zu sein in der Anerkennung jener Leonardoschen Zeichnungen, deren Strichlage nicht von links nach rechts geht. Leonardo hatte nämlich in Mailand einige Schüler, die ihn meisterhaft nachahmten, und ihm manches Mal sehr nahe kamen. Er selbst hat jedoch, wie ich glaube, höchst selten sog. schöne, d.h. fein und niedlich ausgeführte Zeichnungen gemacht; handelte es sich bei ihm doch meistens nur [darum], den flüchtigen Gedanken auf dem Papier festzubannen. Auch glaube ich kaum, dass ihm der Einfall kommen konnte, einen Hund bei seinem Abendmahl anzubringen.« Giovanni Morelli (March 30, 1880): »Mein lieber Freund, Sie haben da eine wahrhaft Ihrer würdige Beschäftigung gefunden, und ich verspreche mir, dass Sie die noch dunkle Frage meisterhaft lösen werden. Ich rate Ihnen, vorderhand noch sehr vorsichtig zu sein in der Anerkennung jener Leonardoschen Zeichnungen, deren Strichlage nicht von links nach rechts geht. Leonardo hatte nämlich in Mailand einige Schüler, die ihn meisterhaft nachahmten, und ihm manches Mal sehr nahe kamen. Er selbst hat jedoch, wie ich glaube, höchst selten sog. schöne, d.h. fein und niedlich ausgeführte Zeichnungen gemacht; handelte es sich bei ihm doch meistens nur [darum], den flüchtigen Gedanken auf dem Papier festzubannen. Auch glaube ich kaum, dass ihm der Einfall kommen konnte, einen Hund bei seinem Abendmahl anzubringen.« |

Jean Paul Richter (April 11, 1880): »Sie haben mich gütigst in Ihrem letzten Brief gewarnt, recht vorsichtig zu sein in der Anerkennung der Zeichnung mit Strichlage nicht von links aus. Ich habe bis jetzt von annähernd dreihundert Blättern seiner Handschrift mehr oder weniger exzerpiert, was sich auf die Kunst oder seine persönlichen Verhältnisse und Schicksale bezieht – im Lauf der letzten drei Monate. Aber selbst in den Maschinenzeichnungen und in solchen verwandter Art ist ausnahmslos, wie gewiss auch im Codex Atlanticus die Strichlage von links ausgehend und nicht minder begründet finde ich Ihren Grundsatz, Leonardo könne nur höchst selten fein und niedlich ausgeführte Zeichnungen gemacht haben.« Jean Paul Richter (April 11, 1880): »Sie haben mich gütigst in Ihrem letzten Brief gewarnt, recht vorsichtig zu sein in der Anerkennung der Zeichnung mit Strichlage nicht von links aus. Ich habe bis jetzt von annähernd dreihundert Blättern seiner Handschrift mehr oder weniger exzerpiert, was sich auf die Kunst oder seine persönlichen Verhältnisse und Schicksale bezieht – im Lauf der letzten drei Monate. Aber selbst in den Maschinenzeichnungen und in solchen verwandter Art ist ausnahmslos, wie gewiss auch im Codex Atlanticus die Strichlage von links ausgehend und nicht minder begründet finde ich Ihren Grundsatz, Leonardo könne nur höchst selten fein und niedlich ausgeführte Zeichnungen gemacht haben.« |

Jean Paul Richter (May 1, 1880): »Von Zeichnungen [in Paris] einige wenige sehr fein ausgeführte Figürchen (etwa vier)[,] alles übrige ist flüchtige Skizze, und nicht eine ist //// oder in ähnlicher Lage schattiert.« Jean Paul Richter (May 1, 1880): »Von Zeichnungen [in Paris] einige wenige sehr fein ausgeführte Figürchen (etwa vier)[,] alles übrige ist flüchtige Skizze, und nicht eine ist //// oder in ähnlicher Lage schattiert.« |

Jean Paul Richter (May 24, 1880): »Gestern war ich seit langer Zeit das erste Mal in Windsor, die Leonardo-Handzeichnungen mit dem älteren darauf bezüglichen Brief von Ihnen in der Hand aufs neue zu prüfen. Was sich mir schon in sämtlichen Handschriften, welche Skizzen enthalten, bestätigt hatte, war auch hier das überraschende Ergebnis. Wenn irgendeine Zeichnung auf den ersten Blick den Eindruck möglicherweise unecht zu sein auf mich machte, so waren es bei näherem Zusehen immer solche, die //// und in ähnlicher Lage[,] aber nicht \\\\ schattiert waren.« Jean Paul Richter (May 24, 1880): »Gestern war ich seit langer Zeit das erste Mal in Windsor, die Leonardo-Handzeichnungen mit dem älteren darauf bezüglichen Brief von Ihnen in der Hand aufs neue zu prüfen. Was sich mir schon in sämtlichen Handschriften, welche Skizzen enthalten, bestätigt hatte, war auch hier das überraschende Ergebnis. Wenn irgendeine Zeichnung auf den ersten Blick den Eindruck möglicherweise unecht zu sein auf mich machte, so waren es bei näherem Zusehen immer solche, die //// und in ähnlicher Lage[,] aber nicht \\\\ schattiert waren.«(Source: Irma Richter/Gisela Richter (Ed.), Italienische Malerei der Renaissance im Briefwechsel von Giovanni Morelli und Jean Paul Richter 1876–1891, Baden Baden 1960, pp. 88, 90, 112, 114f., 117, 119) |

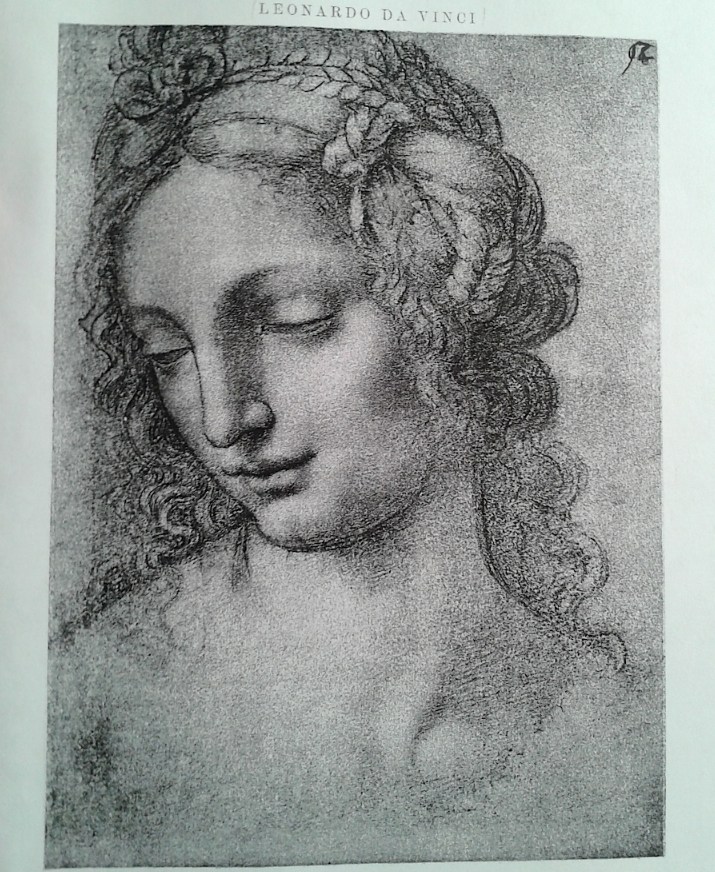

Commentary to the above (DS): Commentary to the above (DS):»Requisiten der Echtheit« (›properties of authenticity‹): Only from the German original text it is obvious that Giovanni Morelli, above, is referring to the world that had been his passion prior to giving priority to connoisseurship, namely the world of the theatrical stage, the theatre, with its props like for example the skull of Yorick that Hamlet muses upon (or, as here, ›properties of authenticity‹); not to the actual actors on scene, he is referring, nor to the stage, or to a spoken text (not to mention an intellectual or spiritual content), but to »properties of authenticity«; and one might be reminded of the fact that Morelli is actually known for shifting the attention of attributional studies from the more obvious ›signature properties‹ towards the margins of a stylistic paradigm where individual authorship might reveal itself more clearly; at the time of writing, however, ›left-handed hatchings‹ were not yet seen as obvious ›signature properties‹ (but, as Morelli had it then, as props, and this among other, equally important props), but in the mean time this may have changed, and, given this evolution, one might be led to think now about hierarchies of properties as such and about the relative weight given to various classes of properties within such hierarchies. Jean Paul Richter, by the way, was the owner of a drawing that he had attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and that he gave to auction as being by Leonardo da Vinci in 1913 (›Head of a young woman‹; »sans doute« a ›study for the Louvre Virgin of the Rocks‹; modern scholarship, however, has either lost trace of that drawing (whose whereabouts are presently unknown to me) or silently decided to ignore it as irrelevant; in the copy of the 1913 auction catalogue an anonymous hand did not accept the attribution either, voting for ›Luini‹ instead; from the reproduction of the drawing I am only able to detect shadings that go /// (left shoulder and hair of the sitter); these, however, might be discussed as well, but are not exactly hatchings of the type that start from a contour, the type that we are discussing here (pictures below: DS).   |

|

Kenneth Clark (source: Kenneth Clark, The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, second edition, revised with the assistance of Carlo Pedretti, volume one, London 1968, p. xvii): Kenneth Clark (source: Kenneth Clark, The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, second edition, revised with the assistance of Carlo Pedretti, volume one, London 1968, p. xvii):»Finally there is the simple fact that all Leonardo’s drawings are done with the left hand and the diagonal shading invariably runs down from left to right. The connoisseur cannot help feeling suspicious of a criterion which reduces all his arts to such an obvious material formula. But much as he may dislike it, he must admit that this criterion has never been proved wrong. Almost every drawing attributed to Leonardo that is shaded from right to left is either unlike him in other respects or is demonstrably a copy.« [note] 2 [as to the above]: »A possible exception is the St Jerome, ’571. But its quality may well justify an attribution to Bramante, as suggested by Professor Suida […].« (cont.) »Two instances in this collection are the famous drawing of a tree, ’417, which has finally been proved to be a Cesare da Sesto, and the study of a horse’s legs, ’299, which I should not have questioned had it been shaded from left to right: but, once suspected and investigated, it turned out to be a copy of a drawing in Budapest. It does not, of course, follow from this that all drawings shaded from left to right are genuine Leonardos. This was a trick which the pupils could imitate; but it was pointless and awkward for a right-handed man, and was done only by the dullest copyists. An example is the copy of the studies for the Virgin and the Cat, ’564, which is so tame that it may have been done for purpose of record rather than deception. […]« |

My commentary to the above: My commentary to the above:With all due respect: but this is typical ›rhetoric of attribution‹: On the one hand ›the criterion has never been proved wrong‹, on the other hand it is never to be used in isolation (so, of what weight is it?). Why not stating, with Morelli (who is more straight forward here, at least in his first statement, cited above), that the hatchings argument does only matter, is only relevant, if all the other ›properties of authenticity‹ are there: i.e. in combination with a set of properties. Now: whatever these other ›properties of authenticity‹ might be, Clark does himself admit that in one case, for him, everything was in the order, and only the hatchings made him suspicious. It comes down to the question, apparently, if these ›left-handed hatchings‹ are easy to produce or not, and as I have said above, from my point of view, it is most easy to produce such hatchings in various ways if needed and, by the way, it strikes me that, generally, it is underestimated the large number of (mostly unknown) draftsmen and draftswomen at all times that actually dispose of extraordinarily great drawing skills. As to ›self-fullfilling-prophecy‹: this phenomenon can be studied here as well: if we assume that all Leonardo drawings were made by his left hand (yet compare what Nicholas Turner has to say, below, that Leonardo could, if necessary, produce ›right-handed hatchings‹), and if we tend to exclude all drawings from his oeuvre that do not show ›left-handed-hatchings‹, this might result in a ›cleaned oeuvre‹. A game of self-confirmation produces as a result what is being expected, a game that is being played despite of the numerous ifs and buts also to be found in these very quotes, from Morelli to Clark and beyond. |

|

| Patricia Trutty-Coohill (as reviewing Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, ed. by Carmen C. Bambach, Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition catalogue of 2003, in: The Sixteenth Century Journal Vol. 35, No. 2 (Summer, 2004), pp. 635-637): »For example, in Verrocchio’s Young Woman from Christ Church, Bambach first examines the entire drawing, then moves into details that show the characteristic techniques of Verrocchio and his studio, then focuses on reworkings in wash and left-handed hatching and finally ›ponders‹ whether the reworkings might be the work of young Leonardo. After drawing us in, she moves us an arm’s length away, so that we can consider the reasons for the reworkings. In this way, she fulfills her primary objective: to provide a context in which ›to look attentively at Leonardo’s drawings as works of art full of telling clues about their making and their use, rather than as abstract illustration of content‹ (8).«  (Picture: chch.ox.ac.uk) (and check out the above mentioned catalogue here: http://books.google.ch/books?id=QwQxDJMKRE4C&pg=PA36&lpg=PA36&dq=left-handed+hatchings&source=bl&ots=Nz6vBuBJJu&sig=7ws9UAZVtgBCiPsf-9jMMQX8vTk&hl=de&sa=X&ei=9vxoVIWsM4jJPcbTgNAE&ved=0CDYQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=left-handed%20hatchings&f=false) |

|

Nicholas Turner (from his 2008 expertise concerning the so-called ›Bella Principessa‹; see: http://www.lumiere-technology.com/images/Download/Nicholas_Turner_Statement.pdf): »Beyond first-hand examination of the Portrait of a Young Woman, an important starting-point for any serious consideration of its quality is the sequence of high-resolution digital scans made early in 2008 by Lumière Technology […]. Introducing this formidable array of technological support is a remarkable colour scan of the whole portrait, which may be enlarged several times life-size, giving the viewer an opportunity to understand – better than with the naked eye – the exceptional quality of the drawing’s execution. Among the more noteworthy elements revealed in this way is the extent of the left-handed shading – the ›signature feature‹ and most visible testimony of Leonardo’s authorship – especially in the face and neck and in the left background along the sitter’s profile. These areas of parallel hatching in pen in the background, behind the sitter’s face, are blocked in to give a contrast to the highlights of her flesh. Similar dense crosshatching is to be found throughout the artist’s drawings. Especially good examples of the type, also in pen, are found among Leonardo’s studies of anatomical subjects, for example the series of studies of the human skull in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle (inv. nos. 19058r & v, 19057r & v, and 19059r; Zöllner, 2007, nos. 257-61, all repr.). The hatching strokes in the new portrait taper from lower right to upper left, just like the strokes defining the left background in the skull studies. Carlo Pedretti’s observation (Abstract of introduction to the monograph Leonardo infinito by Alessandro Vezzosi, published in July 2008, [available as .pdf on the Lumière Technology website]) that Leonardo’s strokes normally went from upper right to lower left applies to the shading on the right side of the skulls, not to the strokes to the left of the skulls. In other words, Leonardo wisely moved the pen from the object’s contour outwards into the background, avoiding any possible stray overlapping back into the finished object. It is thus not surprising that he would have directed the pen away from the sitter’s face and neck towards the upper left in the new portrait. Had there been background shading on the right side of the new portrait, one would have expected the lines to move from upper left to lower right. However, there was no need for any shading on the right side to set off the dark hair against the neutral light background.« |

Pietro C. Marani (as quoted by telegraph.co.uk in 2010, when being asked if he believed that Leonardo da Vinci was the author of the drawing of the so-called ›Bella Principessa‹; picture on left: museoscienza.org): Pietro C. Marani (as quoted by telegraph.co.uk in 2010, when being asked if he believed that Leonardo da Vinci was the author of the drawing of the so-called ›Bella Principessa‹; picture on left: museoscienza.org):»›The fact that one is looking at a drawing by a left-handed artist does not carry any weight: there exist copies of drawings by Leonardo made by imitators which present this particular characteristic – by, Francesco Melzi, for example, as Kenneth Clark and others have already written.‹«  |

|

Further Reading: Alexander Perrig, Michelangelo Studien I. Michelangelo und die Zeichnungswissenschaft – Ein methodologischer Versuch –, Frankfurt a.M/Bern 1976 (the most comprehensive and systematic attempt to conceptualize the techniques of drawing) Further Reading: Alexander Perrig, Michelangelo Studien I. Michelangelo und die Zeichnungswissenschaft – Ein methodologischer Versuch –, Frankfurt a.M/Bern 1976 (the most comprehensive and systematic attempt to conceptualize the techniques of drawing) |

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Thank you for visiting the Online Journal (and think also of visiting the Virtual Museum of Art Expertise…) http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/TheVirtualMuseumOfArtExpertise |

A necessary addendum as to drawing techniques:

In recent times the discussion as to shading techniques in Leonardo and works attributed to Leonardo has also shifted to a microlevel. Which means that instead of discussing the mere directions of shadings one has begun to discuss also curvings of strokes, perhaps being indicative of left- or right-handedness.

In my view we have entered a stage of even bigger confusion, because firstly: connoisseurs of the past, as can be seen above, have only discussed directions of strokes (perhaps taking for granted a certain curving, or not taking it for granted, we don’t know). And secondly: since some of those regarding so-called left-handed strokes (with curving) being indicative of left-handedness seem to have an all to simplified idea of drawing techniques.

By which I mean: one does not necessarily do hatchings with a movement of the arm (having your ellbow fixed on a table); there is also the possibility of a movement coming from the wrist. And again: if I am putting a sheet upside down (just for checking a composition), I can do – as a right-hander and without a problem, namely with a movement coming from the wrist – shadings with a curving which is, according to this simplistic model, regarded as being indicative of left-handedness (and I can also do this without turning the sheet upside down, which, however requires a focus on producing or avoiding curvings).

In sum: we should consider all of these possibilities, various drawing techniques, and also various situations a draftman faces: in terms of size, in terms of having time (or having to work fast), and above all; in terms of what a draftman wants, given a particular situation. To elaborate or not to elaborate a drawing. To work spontaneously and freely. And perhaps also: to play around, with the aim of producing curvings, or not producing curvings. If this does sound polemical: the aim of all the above said is simply: to work against simplification. (DS; 5/2016).

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS