M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

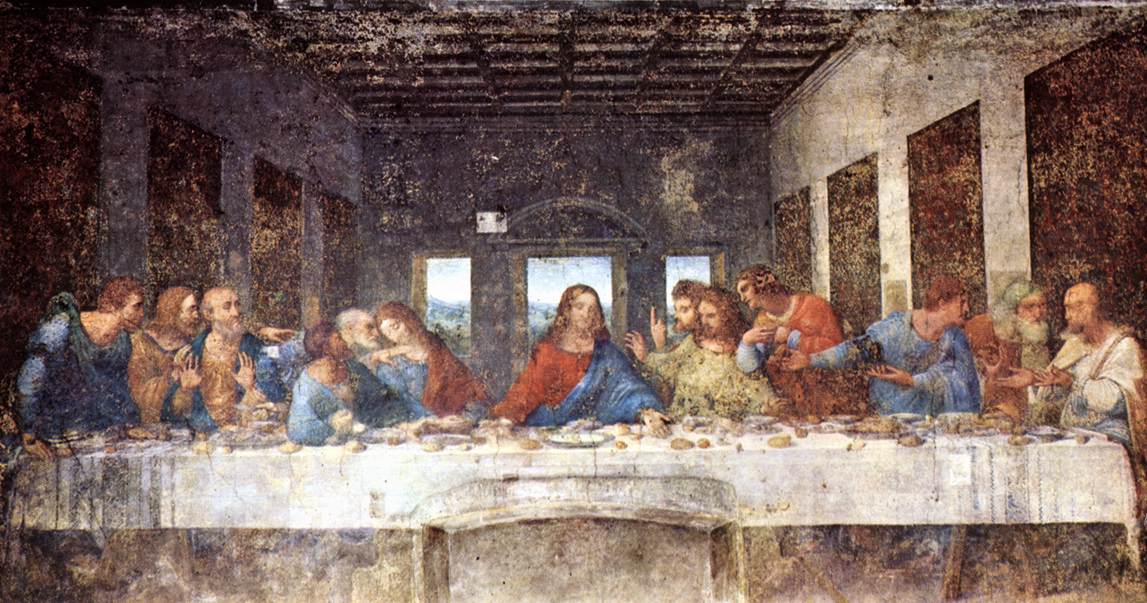

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM How to Tell Leonardo from Luini |

HOW TO TELL LEONARDO FROM LUINI

Isn’t it refreshing to read that there once was a man ten times greater than Leonardo?

John Ruskin wrote that, in his 1869 book The Queen of the Air.

And I can see all the Berensons and Berenson epigones raising their eyebrows.

Here we learn what Michel Foucault meant if speaking of ›discourse‹:

if we are thinking within a certain frame of reference that includes rules how to see things,

how to interpret things, how to speak about certain artists, and not to forget:

how not to speak about certain artists, we end up with stereotype valuations

that become monopolies.

And if I am recalling Ruskin’s appraisal of Bernardino Luini here, this is to remind that discourses

may be acting invisibly; and they become visible and graspable if challenged. By another

discourse. With alternative rules. With alternative valuations and interpretations.

Reminding this is not meant to value Leonardo or Luini, but to remind how different the results

of a Berensonian discourse, compared to a Ruskinian discourse may be. In terms of

what we see (and how we value).

And this is why I am assembling here some views on Leonardo and Luini. On Leonardo

compared to Luini. And on Luini compared to Leonardo.

And we may find – and this may be the wanted result here –, that

often it was – and it is – not that easy to tell Leonardo from Luini (especially if yet

our reference works of art may be mislabelled).

But some authors tried to tell one from the other; and we may use their attempts to come up

with other descriptions.

And perhaps definitions of identifiers. And perhaps valuations. Our own ones.

(On the left only pictures ascribed to Luini, on the right only pictures by Leonardo;

our title image uses a picture by Luini)

John Ruskin:

»[p. 210]

157. The best examples of the results of

wise normal discipline in Art will be found in

whatever evidence remains respecting the lives

of great Italian painters, though, unhappily,

in eras of progress, but just in proportion to

the admirableness and efficiency of the life, will

be usually the scantiness of its history. The

individualities and liberties which are causes

[p. 211]

of destruction may be recorded; but the loyal

conditions of daily breath are never told. Be-

cause Leonardo made models of machines, dug

canals, built fortifications, and dissipated half

his art-power in capricious ingenuities, we have

many anecdotes of him; — but no picture of

importance on canvas, and only a few withered

stains of one upon a wall. But because his

pupil, or reputed pupil, Luini, laboured in con-

stant and successful simplicity, we have no

anecdotes of him; — only hundreds of noble

works. Luini is, perhaps, the best central type

of the highly trained Italian painter. He is

the only man who entirely united the religious

temper which was the spirit-life of art, with the

physical power which was its bodily life. He

joins the purity and passion of Angelico to the

strength of Veronese: the two elements, poised

in perfect balance, are so calmed and restrained,

each by the other, that most of us lose the sense

of both. The artist does not see the strength,

by reason of the chastened spirit in which it

is used; and the religious visionary does not

recognize the passion, by reason of the frank

human truth with which it is rendered. He is

a man ten times greater than Leonardo; — a

»…obschon die Bildung der Hände, die etwas allgemeine Schönheit der Königstochter und ihrer Magd,

die glasige, verblasene Oberfläche des Nackten deutlich auf den Schüler hinwies.«

»…auch selbst schon an der Länge der Füsse…« (picture: Sailko)

[p. 212]

mighty colourist, while Leonardo was only a fine

draughtsman in black, staining the chiaroscuro

drawing, like a coloured print: he perceived

and rendered the delicatest types of human

beauty that have been painted since the days

of the Greeks, while Leonardo depraved his

finer instincts by caricature, and remained to the

end of his days the slave of an archaic smile:

and he is a designer as frank, instinctive, and

exhaustless as Tintoret, while Leonardo's de-

sign is only an agony of science, admired chiefly

because it is painful, and capable of analysis in

its best accomplishment. Luini has left nothing

behind him that is not lovely; but of his life I

believe hardly anything is known beyond rem-

nants of tradition which murmur about Lugano

and Saronno, and which remain ungleaned.

This only is certain, that he was born in the

loveliest district of North Italy, where hills, and

streams, and air, meet in softest harmonies.

Child of the Alps, and of their divinest lake,

he is taught, without doubt or dismay, a lofty re-

ligious creed, and a sufficient law of life, and of

its mechanical arts. Whether lessoned by Leo-

nardo himself, or merely one of many, disciplined

in the system of the Milanese school, he learns

Here we see what Morelli and his pupil Jean Paul Richter mentioned as the Luinesque ›double-ear‹

(»Doppelohr«; see Seybold, Das Schlaraffenleben der Kunst).

[p. 213]

unerringly to draw, unerringly and enduringly

to paint. His tasks are set him without ques-

tion day by day, by men who are justly satis-

fied with his work, and who accept it without

any harmful praise or senseless blame. Place,

scale, and subject are determined for him on

the cloister wall or the church dome; as he

is required, and for sufficient daily bread, and

little more, he paints what he has been taught

to design wisely, and has passion to realize glo-

riously: every touch he lays is eternal, every

thought he conceives is beautiful and pure: his

hand moves always in radiance of blessing;

from day to day his life enlarges in power and

peace; it passes away cloudlessly, the starry

twilight remaining arched far against the night,

158. Oppose to such a life as this that of

a great painter amidst the elements of modern

English liberty. Take the life of Turner […].«

(Picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

(Picture: pinterest.com ; relatively unknown: Luini’s privately owned Boy with a Puzzle)

1838: Johann David Passavant: »Ehe wir jedoch über den Einfluss des Leonardo auf die Maler in Mailand abschliessen, haben wir zuvor noch den Meister Bernardino Luvino [note: »Luvino ist ein Städtchen am Lago maggiore. Vasari nennt ihn irrig da Lupino.«] oder Luino zu erwähnen; denn wenn gleich Lomazzo (Tratt. p. 421) berichtet, dass jener zu gleicher Zeit mit Gaudenzio Ferrari Schüler bei Stefano Scotto gewesen, so zeigen doch des Luino Gemälde entschieden den grossen Einfluss, welchen Leonardo auf ihn ausgeübt. Jedenfalls hat er dessen Werke mit solchem Erfolge studiert, dass keiner der Leonardischen Schüler ihnen in gewisser Hinsicht näher dürfte gekommen seyn, als Luino in einzelnen Werken, die denn auch allgemein dem grossen Florentiner selbsten zugeschrieben worden sind. Auch scheint Raffael auf seine Kunst, namentlich auf die Behandlung der Gewänder eingewirkt zu haben, wenn auch nicht unmittelbar, doch durch die in alle Welt verbreiteten Marc Antonischen Kupferstiche nach dessen Compositionen. Neben dem Hinblicken nach diesen zwei grossen Meistern entwickelte Luino aber auch seine Eigenthümlichkeit, welche durch Naivität, einen grossen Liebreiz in den Köpfen und eine grosse Einfalt in seinen Anordnungen und Compositionen höchst anziehend wird. Tief charakteristisch und energisch ist er aber niemals; hiezu fehlte es ihm an Schärfe. Daher auch seine Zeichnung etwas stumpf ist, was besonders bei den Extremitäten, namentlich den Händen seiner Figuren auffällt. Sein Colorit ist dagegen blühend, sein Farbenauftrag saftig und pastos, aber etwas geleckt. Im Helldunkel ahmte er den Leonardo nach.« (Beiträge zur Geschichte der alten Malerschulen in der Lombardei, in: Kunst-Blatt 19, September 1838 [various issues], p. 295)

»…and dissipated half his art-power in capricious ingenuities« (upper picture: ticino.ch)

1855ff.: Jacob Burckhardt: »Von den mailändischen Schülern hat Bernardino Luini (st. nach 1529) bei seinen frühsten Arbeiten den Lionardo noch nicht gekannt, bei denjenigen seiner mittlern Zeit ihn am treusten reproducirt, bei den spätern aber auf der so gewonnenen Grundlage selbständig weiter gedichtet, wobei es sich zeigt, dass er mit unzerstörbarer Naivetät sich nur das von dem Meister angeeignet hatte, was ihm gemäss war. Sein Sinn für schöne, seelenvolle Köpfe, für die Jugendseligkeit fand bei dem Meister sein Genüge und die edelste Entwicklung, und noch seine letzten Werke geben hievon das herrlichste Zeugniss. Dagegen ist von der grossartig strengen Composition des Meisters gar nichts auf ihn übergegangen; man soll glauben er hätte das Abendmahl nie gesehen (obschon er es einmal nachgeahmt hat), so linienwidrig und ungeordnet sind seine meisten bewegten Scenen. Auch drapirt er oft ganz leichtfertig und gleichgültig. Dafür besass er stellenweise, was keine Schule und kein Lehrer verleiht, grossgefühlte, aus der tiefsten Auffassung des Gegenstandes hervorgegangene Motive.

Über die Umgebung von Mailand hinaus kommen nur kleinere, vereinzelte Bilder von ihm vor. Ausser den genannten (S. 863) ist das Bedeutendste die Enthauptung Johannis, in der Tribuna der Uffizien, lange dem Lionardo beigelegt, obschon die Bildung der Hände, die etwas allgemeine Schönheit der Königstochter und ihrer Magd, die glasige, verblasene Oberfläche des Nackten deutlich auf den Schüler hinwies. Der Henker grinsend und doch nicht fratzenhaft, das Haupt des Täufers ungemein edel. So charakterisirt die goldene Zeit! Der in der Nähe hängende Johanneskopf Corregio’s gehört daneben dem modernen Naturalismus an. […]«

(Source: Der Cicerone, p. 867 (p. 121 in the critical edition))

1880: Giovanni Morelli: »[…] jeder gründliche Kenner wird, auch selbst schon an der Länge der Füsse, in jenen Gestalten [of the Atlas fresco then in the Casa Melzi, Borgo Nuovo, Milan, now in the Castello Sforcesco] die Art des B. Luini erkennen; […].«

(Source: Die Werke italienischer Meister in den Galerien von München, Dresden und Berlin, p. 78, note, beginning on p. 77; Luini, and not that of Bramantino, as Crowe and Cavalcaselle had it)

»Dem Argellati zufolge (Scrip. Mediol. II, 816) war Bernardino der Sohn des Giovanni Lutero von Luino, einem Flecken am Lago maggiore. Ueber das Jahr seiner Geburt sind wir noch immer im Dunkeln; doch würde ich dieselbe jedenfalls statt in’s Jahr 1470, wie man gewöhnlich annimmt, in den Zeitraum zwischen 1475 und 1480 setzen. Auch machen, wie mir scheint, sowohl Herr Direktor Meyer als auch die Herren Cr. und Cav. (II, 43) mit Unrecht den Luini zum Schüler Lionardo’s. In seiner grossen »Beweinung Christi« […], im Chore der Kirche S. Maria della Passione zu Mailand, das wohl das älteste unter den uns bekannten Werken des Luini sein dürfte (etwa zwischen 1505-1510), erweist sich derselbe noch als ein durchaus lombardischer Meister, der auch nicht die leiseste Spur Lionardischer Einflüsse, wohl aber deutlich die Schule des Ambrogio Borgognone, nebst mannichfachen Einwirkungen des Bramantino verräth […].

Erst in seiner zweiten Manier (etwa von 1510-1520) erscheint in seinen Werken die Nachahmung Lionardo’s […].

In seiner dritten, s.g. blonden Manier (von 1520-1529) tritt Luini in seiner vollen Freiheit und Unabhängigkeit uns entgegen. In diese Zeit fallen wohl seine besten Werke, wie z.B. der Freskenzyklus im »Monastero maggiore« zu Mailand; Maria mit dem Kinde, im Besitze der Wittwe Arconati-Visconti zu Mailand; das herrliche Poliptychon in der Pfarrkirche von Legnano; die Fresken in Saronno; die drei Bilder im Dome von Como; die Fresken in Lugano. Vom Jahre 1529 an verstummt alle Kunde über Luini; er dürfte also schon in jenen Jahren gestorben sein. Die Mehrzahl seiner Bilder ist unbezeichnet, ich kenne deren nur vier, die seinen Namen tragen, und alle vier gehören seiner letzten Epoche an […; the omitted note shows that Morelli has done archival research on Luini]. Sowohl er wie auch sein Nebenbuhler Gaudenzio Ferrari sollen, nach Lomazzo, neben der Malerei auch die Dichtkunst gepflegt haben […; the omitted note deals with drawings by or attributed to Luini] […].«

(Source: op. cit., p. 478ff.)

(for Morelli, Luini and Villa Sommariva/Villa Carlotta in 1846 see by the way the introductory essay to my Giovanni Morelli monograph; and for the problem of the Leonardesque shape of ear see here)

(Picture: DS)

1907: Bernard Berenson: »[p. 117] Enough perhaps has been said to justify my want of enthusiasm for such bewitching Leonardesque heads as the »Belle Colombine« of St. Petersburg, and the »Lady with the Weasel« at Cracow, and to prepare the reader for my estimate of Luini, Sodoma, Gaudenzio Ferrari, and Andrea Solario.

Luini is always gentle, sweet, and attractive. It would be easy to form out of his works a gallery of fair women, charming women, healthy yet not buxom, and all lovely, all flattering our deepest male instincts by their seeming appeal for support. In his earlier years, under the inspiration of the fancy-laden Bramantino; he tells a biblical or mythological tale with freshness and pleasing reticence. As a mere painter, too, he has, particularly in his earlier frescoes, warm harmonies of colour and a careful finish that is sometimes not too high.

But he is the least intellectual of famous [p. 118] painters, and, for that reason, no doubt, the most boring. How tired one gets of the same ivory cheek, the same sweet smile, the same graceful shape, the same uneventfulness. Nothing ever happens! There is no movement; no hand grasps, no foot stands, no figure offers resistance. No more energy passes from one atom to another than from grain to grain in a rope of sand.

Luini could never have been even dimly aware that design, if it is to rise above mere orderly representation, must be based on the possibilities of form, movement, and space. Such serious problems seem, as I have said, to have had slight interest for any of Leonardo’s pupils, either because the pictures the master executed at Milan offered insufficient examples, or because the scholars lacked the intelligence to comprehend them. Certainly Marco d'Oggiono’s attempts encourage the conclusion that the others did well to abstain. But the subtlety of Leonardo’s modelling, at least, Luini could not resist; and as he had little substance to refine upon, he ended with such chromolithographic finish as, to name one instance out of [p. 119] many, in the National Gallery »Christ among the Doctors.« His indeed was the skill to paint the lily and adorn the rose, but in serious art he was helpless. Consider the vast anarchy of his world-renowned Lugano »Crucifixion«; every attempt at real expression ends in caricature. His frescoes at Saronno are like Perugino’s late works, without their all-compensating space effects.«

(North Italian Painters of the Renaissance)

And this is by Ruskin: After Luini (in the Chiesa di San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan (picture: ashmolean.org).

(For Luini today see also here.)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS