M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY Interlude I: Threads Intertwining or: The Lombardic Silk Industry in Crisis and the Birth of Scientific Connoisseurship  |

The commonplace that Giovanni Morelli did never practice as a doctor, basically, does match the truth. But nonetheless it is not the whole truth to say that Morelli left his medical studies behind altogether. And here we are explicitly not referring to his later connoisseurial practices, but to his giving advice when his medical advice was sought after, and to his observing what was going on in the world around him.

And in two regards he (as the world around him) had to deal with the paradoxical attempt to observe the unseen. Because the unseen (the seemingly invisible) was causing disaster. Economic desaster and also human desaster: and we are referring to the recurrent outbreaks of the cholera throughout the 19th century; and to the crisis that followed the becoming infected of European silk worm cultures with the pebrine disease. Because Giovanni Morelli got involved, in various ways, in the coming to terms with both crises; that affected him personally because like many of his friends he lived directly or indirectly on Lombardic silk production; and because people he knew became infected with the cholera.

INTERLUDE I:

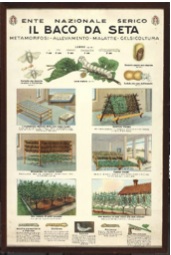

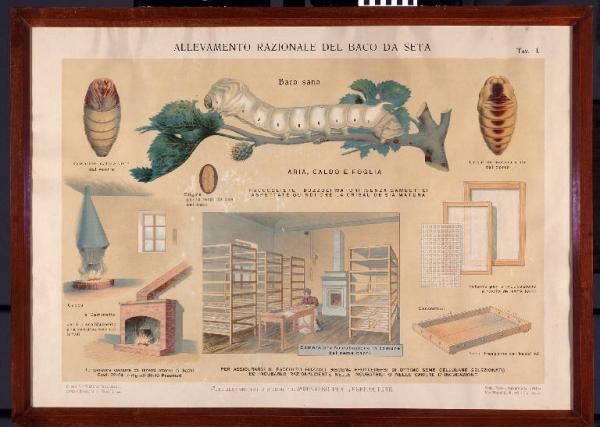

(ONE) THE DOMESTIC SILK MOTH

AND THE CONNOISSEUR

(TWO) THE SMALLEST THINGS, THE UNSEEN

AND THE OVERLOOKED

(THREE) HANDLING ABUNDANCE –

LIVING MODESTLY OR:

A CONNOISSEURS MULBERRY FOREST![]()

(Picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

ONE) THE DOMESTIC SILKMOTH AND THE CONNOISSEUR

THE ECONOMY OF SILK

(Picture: lepiantedafrutto.it)

(Picture: unipv.it; A. Colla)

Mulberry trees Giovanni Morelli noticed in 1861, when travelling with Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, mulberry trees at the shore of the Adriatic Sea, mulberry trees in the Marche.(1)

And one might say: mulberry trees like at home. Like in Lombardy, a land with mulberry forests, and immersed into a particular economy: the economy of silk.

That required whole mulberry forests (or cultures), because the (white) mulberry tree is the food plant of the silkmoth (that shows as a gourmet connoisseur and rejects other food plants), and the economy of silk can also be understood as an economy combining actually two economies: the cultivation of the (white) mulberry tree (morus alba), and the cultivation, the raising – as well as the killing – of the silk moth.(2)

And the economy of silk, one might say, is based on the life cycle of the silk moth, but also on the interrupting of that particular life cycle, because as soon as the silk moth has spun a cocoon, the silk moth, or most of the silk moths, not being allowed to further develop into a butterfly, get killed (for example by boiling). Since the economy of silk is in need of the threads that the cocoon of the silk moth is being made of, and that people wind up, producing a thread. Threads that other people, with

other threads, use to actually spin a thread made out of several, a silk thread that other people work into fabrics. And so on and so forth, until one can speak of a chain of commodities, and until the chain of commodities reaches its end, a consumer, willing to pay for a product.(3)

And innumerable people have found work in this particular economy that encompasses all these various elements and can be seen as a demonstration what division of labour is all about, and also, and already as to the 19th century: what globalization is all about, and only an overall picture does show, how all these elements are interrelated within the system. A system that, at times, might not be visible as such, even if single elements of that system do show, reminding (or just not reminding) that visual education is or might be also about things invisible, about an overall picture that does not show until being made visible, or visibly demonstrated, rendered.

It must have been more than a common déjà vu for Giovanni Morelli, when after his path had led him to become a practitioner of applied connoisseurship, his early scientific studies, as it were, looked back at him.

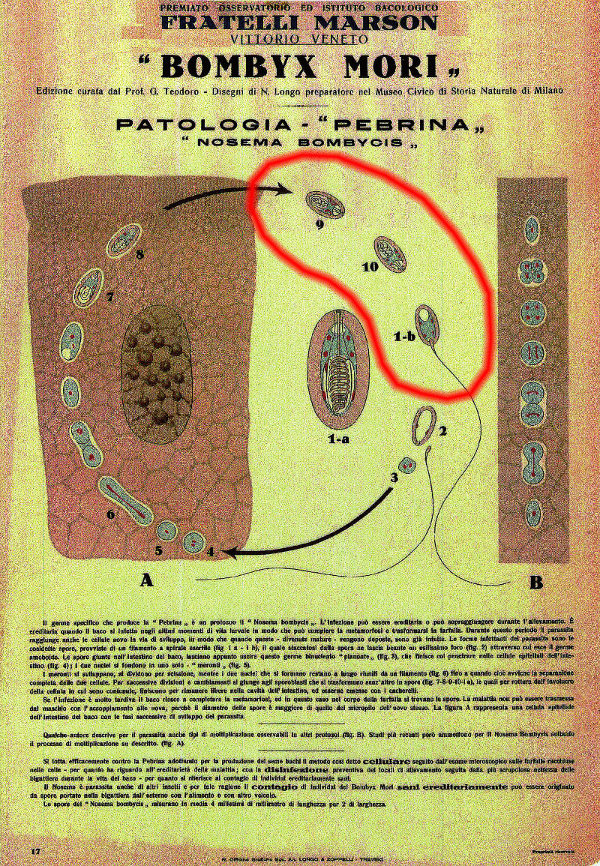

When in 1869 he faced a painting that showed the various developmental stages of the domestic silk moth to him,(4) not something, perhaps that he particularly wished to be reminded of.

And it must have been a déjà vu, because certainly he might have looked at depictions of the silkmoth’s metamorphosis earlier, and even with scientific interest.

Such a depiction was included for example and to be found in books by Georges Cuvier, however important Cuvier might once have been to him (at least his teacher Döllinger had referred to Cuvier as the ›ornament of our time‹),(5) and however important Cuvier was for him now, in 1869. When looking at an example of a Dutch insect still life, rendering the silkmoth’s metamorphosis, a picture that he, tentatively, attributed to Otto Marseus van Schriek.

This picture shows a detail from a picture

Morelli had seen in Cremona, taking also notice that mulberries,

here: black mulberries (stemming from the black mulberry tree,

morus nigra, which is not to be confused with morus alba,

the food plant of the silk moth), are offered to the child,

along with grapes (picture: yelp.de; photo: Martina S.;

painting by Anna Maria Anguissola; compare Morelli 1890, p. 258).

The fruit of the white mulberry tree

(morus alba)

(picture: waldwissen.net)

And it was definitely more than just a common déjà vu, because, for one, Morelli certainly knew also of the Christian meaning that traditionally was given to the silkmoth’s metamorphosis, and he was aware that also in a secular sense one could give a metaphorical meaning, as to a human individual’s development, to the image of a silk moth living through various developmental stages to become, finally, something, for example a butterfly.

And we know that he knew, because, at various stages of his life, Giovanni Morelli actually did use that metaphor to refer to himself, to his having, or to his not yet having become a butterfly (or something else).(6)

All this beared, in a word, on his own identify, and more than that: this very picture visualized also on what ground a large part of the Lombardic economy was based, it visualized how the money was made in Lombardy, and by Lombardic silk merchants, the money that the masters of silk also did spent for culture, and also for pictures. And also for pictures that were being recommended or spotted, or found for them by connoisseurs of art, living on spotting pictures, on buying and selling. Like for example Giovanni Morelli did live, to some degree and ever since the late 1850s, on the buying and selling of pictures.

And of the particular insect still life, tentatively attributed by Morelli to Otto Marseus von Schrieck in 1869, we do only know because Morelli mentioned this (yet unidentified) picture to his relative Giovanni Melli, for whose’s collection Morelli spotted pictures (to inherit these pictures one day, respectively in 1873, be it that there was such an outspoken or unspoken deal as to the matter at that time or not).(7)

(Picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

Here Giovanni Morelli was, and indirectly, although he would have hated to admit it, living also on the economy of silk, partly being represented within that very painting that he saw and when he was living on the economy of the old masters picture trade. And he was indirectly living on the economy of silk, due to these economies intertwining, as he had lived on it before, less indirectly, because he had inherited financial means to acquire property (with silk production that generated an income, for him, as well as for those actually working in an actual sense); and the means to acquire a manor with silk production he had inherited because his father had been a successful silk merchant (who later had combined banking with the trading of silk) and had become a landowner, which can also be seen as a way of dissimulating the fact that someone lived on the economy of silk, like Giovanni Morelli tended to dissimulate the fact. Since he hated, as the man of letters he wanted to be, to be associated with commerce and with (as he used to refer to Swiss people: a »Krämervolk«).(8)

Although his best friends, the Frizzoni brothers, were coming from a family of silk merchants, and represented wealth, also the wealth that was spent on collecting and building, as well as spent on philanthropy, accumulated by being successful entrepreneurs of silk (in production and trade).

In sum: there was no escape from that economy; and in every way Giovanni Morelli was and remained, even as a man of letters, and even as a connoisseur of art, someone who represented the Lombardic economy of silk, and someone who benefitted from it throughout his life.

Even if he did manage, to a remarkable degree, to dissimulate the fact.

An example of a still life (with insects) by Otto Marseus van Schriek,

who might also have depicted the silk moth’s metamorphosis

*

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

We have seen that during the 1850s German connoisseur of art Otto Mündler did replace the Munich-based artist Bonaventura Genelli as a mentor, and that Mündler represented a new role model for Giovanni Morelli.

But moreover Otto Mündler represented other things than merely that: for example the various developmental stages to become, after having been a student of theology, a connoisseur of art.(9) Not something to be foreseen perhaps, but on the other hand, as Morelli was to realize rather fast, a way a man of letters, who also showed a certain propensity for reveries and dreamy musing, could make a living. Securing a certain degree of freedom, that is, of relative independence.

But on the end of the day Otto Mündler, at least for several years, did represent still another thing, and the overall picture does reveal it rather brutally: because this thing was the purchasing power of the English museums, namely the London National Gallery, since Mündler, until he got fired in 1858, acted as a travel agent, meant to acquire pictures for the National Gallery.

And we have, within our overall picture of intertwining economies, take notice not only of English museums and English collectors on the one hand, and of Italian collectors and museums on the other, but also of two national economies, of the purchasing power of the English (and later the German) on the one hand, compared with the purchasing power of the Italians. And this on the market for Italian old master paintings, drawings and sculptures, that at the same time made the cultural heritage of Italy.(10)

And if a Lombardic collector, perhaps advised by Giovanni Morelli, competed with an English collector (perhaps also advised by Giovanni Morelli), a Lombardic economy, particularly, but of course not exclusively, an economy of silk competed with whatever kind of other economy that had resulted in purchasing power.

And within this strategic balance or imbalance, Giovanni Morelli as other Italian and non-Italian connoisseurs had to find their place. And thus in a double sense Giovanni Morelli was sensitive as to how the economy of silk developed, since a) his income on property developed with it (and because it was diminishing, forced him to become more active on the picture market) and b) the purchasing power of Lombardic collectors developed with it (and the more the wealth of Lombardic purchasers diminished the stronger the position of the English, and the more even a patriotic connoisseur was forced to associate with foreign collectors).

In sum: the overall picture does show a situation delicate as it can be, and very sensitive to any kind of disturbance, be it as to the human side of advising and collecting, or as to the economy itself, collecting was based on. And if one did take notice of the arrival of English travelling agents, attempting to carry as much art away as possible from Italy,(11) this caused, naturally, as much disturbance, was, on another level, but still within the same overall picture, one did fear the competition that the Chinese silk production brought into the international market of silk, and as sensitive an observe as professor of theology Veit Engelhardt, did take notice, in his travel accounts, of this very situation that, in the 1840s the Lombardic economy of silk did face.(12)

And things were, as we will see, becoming even more complicated, since influencial English collectors, diplomats, or former diplomats were also being supportive as to politics (namely as to Italian unification), and also, on an economical level, which is why we tend to speak here of political economy, supportive as to the managing of a certain crisis that was to arise within the Lombardic economy of silk. Forcing, in result, upon Morelli a certain loyalty that in a way facilitated things and indeed did help to manage crisis, but on the other hand made, due to competing loyalties that Morelli was to face, things also more complicated (see below).

This, in sum, is the necessary overall picture, necessary to understand how Giovanni Morelli, as a connoisseur of art, was acting, that is, to what degree he was forced and also showed willing to maneuver. Since a crisis showed on the horizon that was going to force him to maneuver. A crisis caused by microscopically small agents, which is why, in the following, we will speak of Giovanni Morelli in regard to the unseen and the (seemingly) invisible, of Morelli being affected by a crisis, and of Morelli helping to manage that crisis by pulling some strings in virtuoso manner, while at the same time, he was developing to the an advocate of scientific connoisseurship.

But first we have to speak again of Giovanni Morelli being confronted with disease, of Morelli being concerned with medicine.

**

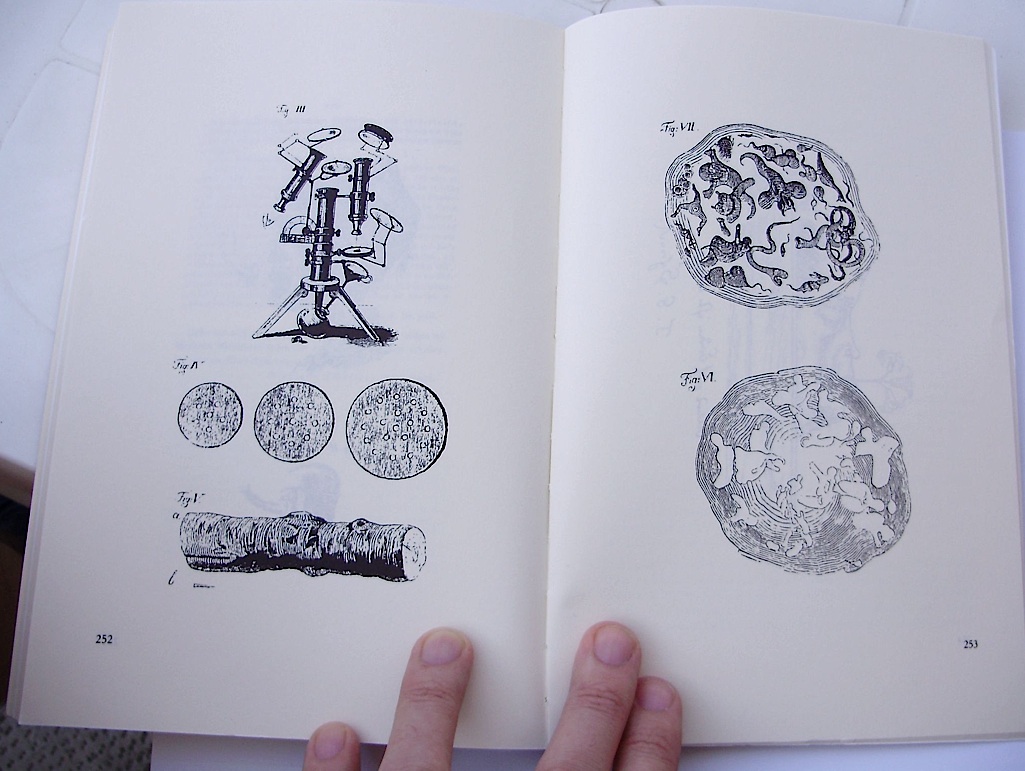

TWO) THE SMALLEST THINGS, THE UNSEEN AND THE OVERLOOKED

MIASM, BAZILLUS AND THE MICROSCOPE

Figures from Giovanni Morelli’s satire Das Miasma diabolicum; on top on the left the so-called Kappelmeier’sche Mikroskop

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a)

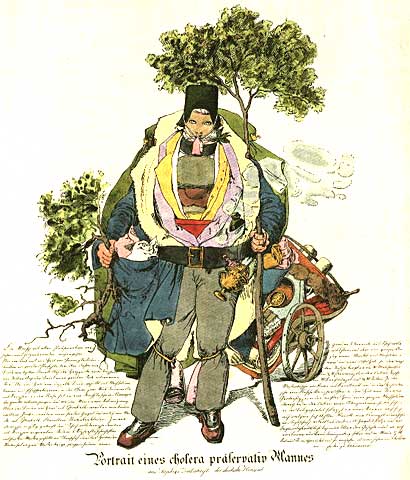

The immediate threat to become infected with the cholera Giovanni Morelli faced at least twice in his life. As hilarious his satirizing of the Munich political confessionalism might read – his Miasma diabolicum of 1839 does, without any doubt, also reflect his experiences as a young student and scholar of the natural sciences, who had participated in the sections of the first Munich victims of the cholera.(13) In explorations, one might say, into the worlds of the unseen, to find the actual causes of a desastrous disease, not yet understood.

And as little as perhaps he might have feared the (seeming) invisible, the unseen, and the danger that became only visible on a microscopic level, as well as the danger to become, on such explorations, infected himself, and as bold he actually did show in case of real, of actual danger – his teacher, professor Ignaz Döllinger the Elder, in fact got infected during or after these sections. And the Munich doctors in fact did connect Döllinger’s death in 1840 with consequences of that having become infected. During or after these sections (see our survey below).

Later in life, during the decade of the 1880s the cholera even entered the house that Giovanni Morelli lived in, in 14, Via Pontaccio, Milan, because his landlord had become infected and brought the disease with him – into the house. And again Giovanni Morelli showed rather couragious and even bold, with returning home and with, apparently, being of help as best as he could. But his landlord, who did overcome the cholera, subsequently died by having become infected with typhus.

The bazillus that caused the disease (the cholera), by that time, had yet been identified, and this by an Italian scholar. But the world of medicine, and also Giovanni Morelli, apparently rather expected German and French scholars to solve the riddle of what exactly caused the disease and how it got spread. And the discovery of the Italian scholar, Filippo Pacini, for mysterious reasons remained unnoticed (and to the present day rather unknown).(14)

Giovanni Morelli, in satirizing, albeit in matters of religion, fusing the imagery of medicine and theology, the adherents of a miasm theory (infection caused by miasms, that is by odours) showed (also) in later years rather as a ›contagionist‹ (infection by a ›contagium‹, a substance), but what exactly happened on a microscopic level might have remained rather mysterious to him as well, who knew, due to his having been a student of medicine, what it was like to look through a microscope, the one tool of modern science that also – on a visual level and in cooperation with his illustrator – he did satirize. By visual means.(15)

Even if the cholera was caused by a ›contagium‹ that was carried around and spread by people, and even if isolation (and not fumigation) might have seemed reasonable to him, he nonetheless (perhaps only being expressive of a general precaution) suggested to his pupil Jean Paul Richter in 1884 to meet preferably in open air, and not in closed rooms (and maybe his scepticism feared that perhaps also contagionism, one day, might be proven wrong, and that it might be about odours too, or about substances in odours and transmitted by odours too).

And as his boldness did show, in relation to the threat of the cholera, his inclination to take any imaginable measure of precaution, his deep and fundamental scepticism also did show here, as it was to show in other areas in life, among them art connoisseurship.

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND THE CHOLERA

(Picture: preussenchronik.de)

According to Adolph Bayersdorfer and Woldemar von Seidlitz (Bayersdorfer 1891, p. 1147; Seidlitz 1891, p. 348) 20-year-old Morelli took part in the sections of the first victims of the cholera at Munich in 1836/37. Which is most likely true (and Bayersdorfer might have heard about this at Vienna in 1873, where the cholera also caused a disaster; see Kretschmer 1999, p. 97): Morelli’s teacher Ignaz Döllinger was participating in these sections (see Kopp 1837), resulting also with Döllinger becoming infected (see Walther 1841, p. 108f.).

Nevertheless Morelli could also treat the subject from its comical side, obviously taking his inspiration for his second literary work, the Miasma diabolicum (Morelli 1839), from the sections as from various measures of precaution against the disease, i.e. from picturesque measures that even at the time could seem ridiculous (compare picture on the left; and compare Bernhard 1983, p. 160).

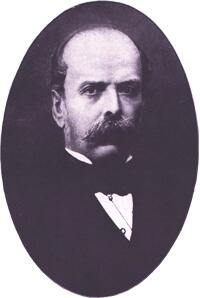

Filippo Pacini

1854: the Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini, thirty years before Robert Koch, discovers the cholera bacillus; the discovery, however, does remain, for mysterious reasons, unnoticed (compare Briese 2003).

(Picture: ph.ucla.edu

1855: »Mein teurer Genelli, die Cholera rüttelt mich aus meiner welschen Faulheit auf, und treibt mich an, Ihnen wiederum zu schreiben. Diese höchst profane u. garstige Krankheit zieht nämlich ihr Netz immer näher um das von uns bewohnte Revier, und da ich mich nicht zu den Unsterblichen zähle, so würde es mir leid tun, diese Erde, wo wir uns beide kannten und liebten, zu verlassen ohne Ihnen, mein verehrter Freund, vorher noch ein Zeichen gegeben zu haben, aus dem Sie ersehen, dass ich trotz meines langen Schweigens doch stets mit Wärme u Freude Ihrer gedachte.

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 15 August 1855; from Taronico)

1867: American writer Mark Twain, according to his The Innocents Abroad (Twain 1875, p. 200), experiences the technique of fumigation at Bellagio.

1884: »Das Beräuchern ist dummes Zeug und nützt gar nichts; das einzige Mittel, das Land vor der Ansteckung wo möglich zu schützen, ist nach der Aussage sowohl der vernünftigern Ärzte bei uns als auch derer in Deutschland, wie z.B. [Robert] Koch und [Rudolf] Virchow, die Isolierung. Wenn man nun bedenkt, dass an 60,000 italienische Arbeiter sich beim Ausbruche der Cholera in Toulon und Marseille befanden, so wäre es wahrlich unverzeihlich gewesen, hätte unsere Regierung das Beispiel der französischen befolgt und, die Hände im Schosse, der Verbreitung der Pest ruhig zugesehen. Ich gebe gerne zu, dass die Sperre an den österreichischen Grenzen unnötig ist – allein die Quarantänen an den französischen und Schweizer Grenzen, durch welche die ital. Arbeiter aus Frankreich in die Heimat massenweise sich zurückflüchten, haben unser Land, wenigstens vorderhand, von der Seuche verschont gehalten. Dass die Tessiner Schleichhändler und Schmuggler laut über die Grenzsperren aufschreien und Skandal machen, ist leicht begreiflich; […]. Mit der Befreiung der Grenzen und der Wiederaufnahme des Schleichhandels werden die Schweizer auch wieder in die alte gute Laune versetzt werden, und wir wollen hoffen, dass dies bald geschehen könne, da, wie es allen Anschein hat, die Cholera in Frankreich am aussterben ist.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 1 August 1884; from ›Crella [San Giovanni] near Bellagio‹)

1884: »Die Erscheinung der Cholera hat uns diesmal einen wahrhaft schreckhaften Blick in die sog. Zivilisation der europäischen Völker, wenigstens jener latinischer Rasse, tun lassen. Statt Fortschritte sehe ich hier nur Rückschritte. Überall siegt die Macht der Unwissenheit über das Recht der Intelligenz. Ich will von dem gegenwärtigen Krieg im Tonchin und in China, von der Verfolgung der Juden ganz absehen, und bloss meine Beobachtungen auf das einschränken, was hierzulande aus Furcht vor der Cholerapest geschieht. Zu keiner Zeit, so viel ich mich besinnen kann, hat man je eine solche Panik, eine solche Erbärmlichkeit der Gesinnung, einen solchen unmenschlichen Egoismus der Gefahr gegenüber schamlos an den Tag gelegt, wie gerade in diesem Jahre, sowohl im südl. Frankreich als hier bei uns, in Sizilien, in Kalabrien und selbst in Spezia. Man glaubt in die Zeiten versetzt zu sein, die Manzoni in seinen Promessi Sposi beschrieben – nur mit dem Unterschied, dass heutzutage bei der Frage der Quarantaine’s nicht nur die Furcht, sondern überall auch die Habgier der Spekulanten ihre grelle Stimme vernehmen lässt. In Kalabrien kam es sogar so weit, dass man einen Eisenbahnzug mit Schüssen empfing und vom Weiterfahren abhalten wollte! So weit sind wir im Jahre 1884 gekommen! Und dabei die Ohnmacht unserer demokratischen Regierung, die es nicht wagt, gegen solche Barbarei mit Entschiedenheit aufzutreten, aus Furcht, unpopulär zu werden. Wahrlich, ich hätte es mir nie gedacht, dass unsere Rasse so tief im Schlamm steckte – oder ist dies vielleicht auch ein Zeichen von Altersschwäche?.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 8 September 1884; from Milan)

1884: »Die Flüchtigen aus Neapel tragen leider das Contagium überall umher und in Rom sind bereits drei Cholerafälle vorgekommen. Die venezianischen Provinzen sind frei vom Übel – ebenso die Ufer unserer Seen; allein[,] wer kann Sie für die nächste Zukunft versichern, dass nicht auch hier in Mailand die Seuche ausbrechen werde?«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 12 September 1884)

1884: later in October Morelli had to face that his landlord Ginoulhiac at Via Pontaccio, a brother-in-law of Gustavo Frizzoni, had become infected with the cholera – which, thus, had entered the very house Morelli lived in at Milan (see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 19 October; from Gorle near Bergamo); on October 20 Morelli planned to go back to Milan to Via Pontaccio to be of help; on October 22 he did inform Richter that Ginoulhiac was doing better (and asked if Richter was afraid of becoming infected if coming to Via Pontaccio as they had actually planned to see pictures); on October 27 Morelli did inform Richter that Ginoulhiac, having overcome the cholera, had died of typhus (see also letter as of October 23); nonetheless Morelli was eager to see Richter at Verona, if preferably not in closed rooms, but only in the open air.

THE PEBRINE CRISIS

(Picture: industriabacologica.it)

Earlier, in the middle of the decade of the 1850s, it was as if the devil in the detail, here a parasite named Nosema bombycis, had known that Morelli was becoming a collector. In 1856. Since this is about the time of the beginning of the pebrine (›pébrine‹) crisis in Lombardic silk industry, caused by the parasite called Nosema bombycis, and resulting with a disease befalling silk moth cultures, and being both infectious and hereditary.(16) And the year of 1856 was the year Giovanni Morelli was becoming a collector.(17)

Again we have to draw the overall picture, to show in what way these two disparate things were – indirectly – connected.

The forced loan, imposed by the Austrian rule after 1848/49, had probably, in addition to general taxes, only had made the situation of landowners like Giovanni Morelli more difficult on an economical level. And it does not seem that Morelli saw of problem, an economic problem, in becoming a collector, that is: in spending money on luxurious goods.(18)

But of course from very early on he might also have seen the buying, in a more playful way, also as a kind of investing. Resulting with a rather smooth transition from being a collector to become somebody who was forced to refinance on the picture market, since at the end of the 1850s crisis had come, since the pebrine disease had reached also Lombardy.

And throughout at least the decade of the 1860s Giovanni Morelli seems to have been rather severely affected by economic crisis, and according to his own stating of facts, his income (and he was referring to cocoon harvest, and to tenants not willing or not able to pay) diminished to less than a third.(19)

In short and as he did state the most clearly if speaking to Mündler: he was in need of money, which is also supported by the fact that after his mother had died in 1867, he had to settle some debts or in any rate was obliged to certain payments.(20)

The crisis forced him to sell pictures as the Lotto double portrait to the National Gallery of London; but the being in touch with English collectors also allowed him to do something that somebody not associating with these circles would perhaps not have been able to do.

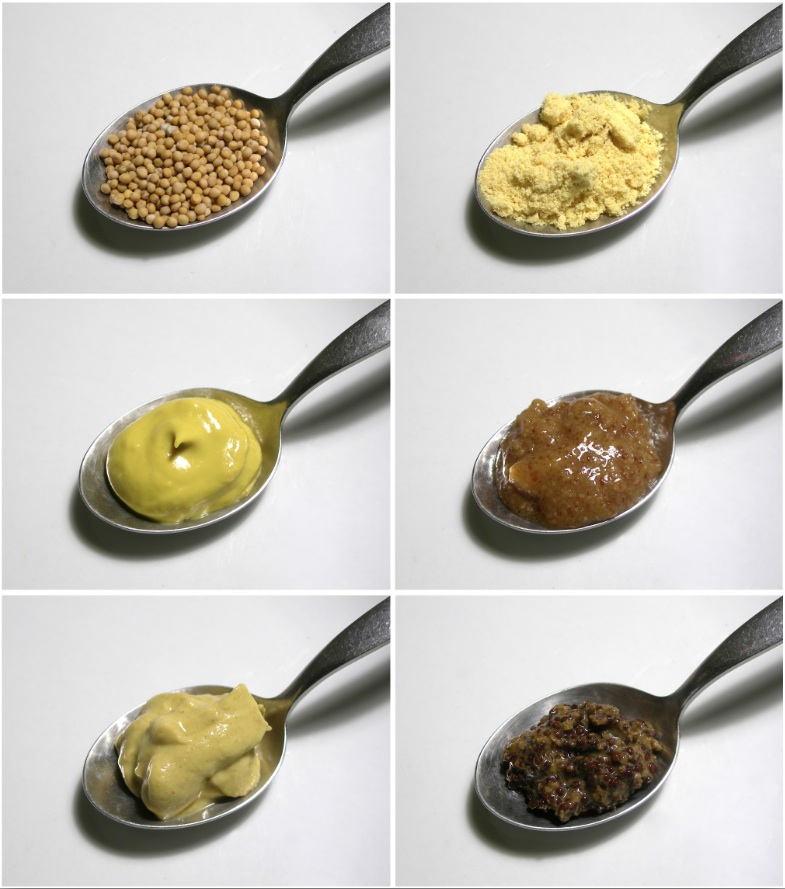

One of the quintessential 19th century teacher on how to look,

namely John Ruskin, in 1872 mused, in front of a glass of diaphanous mustard,

on the chains of commodities ›behind‹ that glass

(picture: Rainer Zenz; for Ruskin musing see Wolfgang Kemp 2000)

*

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP II

(Picture: perfiloepersegni.it)

Because it was globalization that in the end, and according to historians of economy, saved the Lombardic economy of silk. Since it was possible to import sound silk moth eggs from Japan (the country that had been ›opened‹ to commerce during the 1850s).(21)

And what Giovanni Morelli, in his position as a politician and as a connoisseur of art, in 1863 could do, was to secure the support that Austen Henry Layard could provide, Layard, the archaeologist turned politician (later also a diplomat, but at the time working in the English state department), and also a collector of pictures,(22) and it was about English support as to a mission to bring sound silk moth eggs from Japan to Italy. And with Enrico Andreossi, it was a relative of Morelli who actually went to Japan on this very mission, and who – when being in Japan and thanks to Morelli –, could count on the help of the English.(23)

These pulling of strings was only possible for somebody who was at the same time a connoisseur of art (himself supporting and advising English collectors and museum officials) and a politician, whom the elite of Bergamo had elected as their representative in parliament, which also meant that in this mission, this coperative effort to help managing a crisis a whole elite of Lombardic politicians, English politicians and diplomats and Lombardic, particularly Bergamasque silk producers and merchants did cooperate.(24) With culture, next to Risorgimento politics, being one social binder material to bring, to keep this group together.

And while it might be difficult to assess the benefit of this one mission to Japan, and therefore the impact that one man like Giovanni Morelli had within the overall picture, or the impact the help provided by the English actually had – it was Japan, it was in the end globalization that rescued the Lombardic economy of silk.(25)

Giovanni Morelli, as was his habit, did not speak about his role subsequently, resulting with remaining unknown to posterity the share he had had in all this, within a rather spectacular scenery of early globalization and 19th century economy.

**

THREE) HANDLING ABUNDANCE – LIVING MODESTLY OR: A CONNOISSEUR’S MULBERRY FOREST

Lady Layard on picture dealing:

»Henry [Austen Layard] always said that

when once a man took to picture dealing

or to antiquaries he was morally ruined.«

(Lady Layard, Journal, 22 February 1899);

it does not seem, however, that the Layards

ever considered Giovanni Morelli

to be a picture dealer (and morally ruined),

although Jaynie Anderson suggested

that Morelli might have taken 10% commissions

from the Layards (see Anderson 1999a, p. 92)

(picture: britishmuseum.org)

Japanese print referring to the second Perry Mission, resulting with the

›opening of Japan‹ to Western trade in 1853/54

What were the lessons to be drawn, after one had helped to manage a crisis, which now had resulted with the fact that one was, more than one was probably wanting to, obliged to foreign collectors and musuem officials, owing them, in some sense, loyalty or friendship as well as one owed loyalty to one’s home country, a loyalty that demanded to protect the cultural heritage, not allowing, as best as one could, English collectors to carry as much as possible of this heritage away?

Since Giovanni Morelli rather tended to speak about the really important things as little as possible, we can only assume that he was willing to stick to principles, while several principles (his loyalty to his country, his loyalty to his friends) were simply competing inside him. And a third principle was reigning over the two named principles, the principle, if one does like so, of pragmatism. That took the two other principles of various loyalties very serious, but tried to mediate between them as situations demanded.

The perhaps most important lesson as to his own way of living Morelli had probably drawn very early on: that he, himself, was not in need material luxury (except the one or other work of art), and that it could be an elegant, even smooth way to provide for his needs with occasional transactions on the picture market.

The most elegant business model perhaps he was to find naturally: in buying for his relative Giovanni Melli and with the money of Melli, he provided a collection with valuable pieces of art that he would (did he know it from early on?) one day inherit.(26) Being able then, to draw, occasionally on the reselling of single pictures from the collection, to finance a modestly well-to-do way of living.(27)

To be an advisor for various acquaintances and friends probably came also naturally for Morelli, that is, this advising might have been more of his friends’ and acquaintances’ seeking, but Morelli knew also that it was important to radiate an aura of authority. And with beginning to speak of connoisseurship in terms of science, he himself created an ambition that, later, when becoming an art critic who did write on various collections, he had to live up to.

And it may be that he had created expectations, when mentoring, advising collectors like Austen Henry Layard, that grew to be higher, as to scientific standards, than he, later was willing or able to live up to.(28) With his writings. And we have to keep an eye particularly on this dynamic of how an actual rhetoric of scientific connoisseurship developed, while actual practices Morelli never was all too keen to reveal in full.

This was already the pattern, or if one likes so, the business model of the Berensonian world foreshadowed: living on prestige,(29) also on scientific prestige attained by scientific achievements, but forgetting about the ideals that one once had shared: the idea that everything, or at least much, was based on scientific rationality and could, if necessary be explained to the full, and also to the layman.(30)

This, however, remained more of an ambition (also since the layman seldom actually wanted to know everything), and finally remained more of a suggestion, with the connoisseur rarely allowing his clients or his public to exactly follow the reasoning that a connoisseur might be developing in his own head.(31)

This, all in all, was the scenery that developed from a crisis in the Lombardic economy, the economy of silk, and this crisis had a mighty impact on what happened in the seemingly distant field of scientific connoisseurship. Which is why we have kept the picture here, speaking of someone moving in circles of collectors, and moving in the world of the picture market, the museums and also the world of science, of someone moving through a world as abundant as the oceans of Lombardic mulberry forests. Whilst that someone chose to live, as to his own standard of living, rather modestly, combining a displaying of his abilities with also an often very elegant disguising of much of what he did (and enjoying the games of dissimulation also to some degree). Finding his blissfulness not in dealing with pictures, but in living with pictures (and books), and with discussions in small circles of friends rather than in the public arena of science, although also, and also during the 1860s, the ambition was growing, to enter the public arena in days not all too remote from then.

Sir James Hudson

Sir Austen Henry Layard (picture: npg.org.uk)

Emilio Visconti-Venosta (1829-1914)

Ludwig Mond and Henriette Hertz (pictures: Wikipedia; biblhertz.it)

GIOVANNI MORELLI ASSISTING OTHER COLLECTORS – AN OVERVIEW

I. THE YOUNG MORELLI

In 1837 21-year-old Morelli acquires, when still being at Munich, various artists’ drawings for the Frizzoni family (Anderson 1991b, p. 48 (with note 48)); Morelli also later assists the Frizzoni family in their collecting, and particularly Federico Frizzoni in drawing up a catalogue of his collection (Anderson 1999b); moreover Morelli tries to support his friend Bonaventura Genelli in showing works of his to potential Milanese clients as such as an unnamed Milanese lady in 1854 (compare Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 28 October 1854).

II. THE MIDDLE PERIOD

Giovanni Morelli advises and supports a large number of Italian collectors in their collecting; of primal importance is his advising of his relative Giovanni Melli (see Anderson 1999a), because the latter, in 1873, bequeathes his collection, assembled under Morelli’s guidance in 1866ff., to him (and Morelli afterwards chooses to sell again a number of paintings; see op. cit., p. 29f.); Jaynie Anderson enlists, beside this, the names of Enrico Andreossi (another relative), the Marchese Arconati-Visconti (see now Angelini 2013), Baron Giovanni Barracco, Lodovico Belgioioso, Carlo Cagnola, Prince Giuseppe Giovanelli, Donna Laura and Marco Minghetti (for both see here), Carlo Prinetti and Emilio Visconti-Venosta (Anderson 1999a, p. 37);

beside of his supporting of Italian collectors Morelli shows »a very liberal attitude in offering both help and paintings« (Donata Levi) to the London National Gallery’s directors Eastlake, Boxall and Burton, and also to English private collectors such as Sir James Hudson, Sir Austen Henry Layard, Sir Ivor Guest (Layard’s brother-in-law) and John Samuel (see Levi 2005, p. 44; for Samuel see Fleming 1973, p. 9, and also GM to Jean Paul Richter, 28 January 1878 (M/R, p. 27), with Morelli referring to the paintings by Moroni, Moretto, Monbello, ›Bonifacio II‹, Paris Bordone and Salvator Rosa in the Samuel collection); last but not least one might mention that at least in one case Morelli does also advise Bishop Strossmayer (Anderson 1999a, p. 43; compare also Jirsak 2008, p. 46, note 86).

III. THE SENATOR

Beginning in 1884 Anglo-German industrialist Ludwig Mond and his friend Henriette Hertz, the later benefactress of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, are advised in their collecting by Morelli’s pupil Jean Paul Richter; but Morelli himself also begins to support Mond/Hertz on his part (and to interfere with Richter’s advising) (see Seybold 2013); one might mention also Morelli’s assisting of the family of the late Gino Capponi in helping them to draw up a catalogue of the Capponi estate (and to also sell parts or all of the collection; see: Bode [1997], vol. 1, p. 154, and vol. 1, p. 154); and in 1878 Morelli has, moreover, also sold a painting by Hans Baldung Grien entitled Two Witches to the Frankfurt a. M. Städel museum.

One of the paintings Morelli gave away (that is: probably sold) during his last years, namely in 1888: the Saint Jerome in Penitence by Sodoma

(bequeathed to the National Gallery, London, by Ludwig Mond; Morelli particularly did like the background landscape; see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 16 June 1888)

(picture: paintings-art-picture.com)

***

The Giovanni Morelli Collection II: an incoming and outgoing flow of pictures

(compare the list of pictures acquired by Morelli, but not being part of the

Accademia Carrara collection, in Anderson 1999a, p. 210f.)

ANNOTATIONS:

1) Anderson 2000, p. 37. (back)

2) See for example Wunsch 1847. (back)

3) See Federico 1997. (back)

4) Anderson 1999a, p. 76. (back)

5) The importance Georges Cuvier might have had for Morelli has probably rather been exaggerated in the past, since a particular text, containing a praisal of Cuvier, had erroneously been attributed to Morelli (see our Bibliography Raisonné), and in fact had been written by his teacher Ignaz Döllinger, the Elder, and only been copied by Morelli. (back)

6) Compare Morelli 1890, p. 17, as well as Stock (ed.) 1943, p. 97 (GM to the Frizzoni brothers, 10 August 1838: »Da soll sich der Schmetterling [that is, Morelli himself] verpuppen […].«). (back)

7) To Jaynie Anderson we owe a most knowledgeable discussion of the Melli-Morelli relationship with edition also of their correspondence. See Anderson 1999a. (back)

8) For Morelli referring to Bergamo as being a ›dogana‹ of silk see Anderson 1991a (GM to Vieusseux, 3 May 1841). Compare also Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 3 January 1845. (back)

9) See Anderson 1985. (back)

10) For a most knowledgable survey see Levi 2005. (back)

11) For ›carrying away‹ see: Gibson-Wood 1988, p 331, note 36 (William Boxall speaking). (back)

12) For a global view on the history of silk industries see Federico 1997; and for Engelhardt speaking of the situation of Lombardic silk industries, facing Chinese competition, see Engelhardt/Morelli 1846b, p. 2290. (back)

Max von Pettenkofer (1818-1901) in c. 1860

The German chemist Max von Pettenkofer, concerned, among other things,

with finding the causes and ways of how the cholera got spread,

invented also a method to freshen up the varnishes of old paintings by alcoholic vapors

(see Achsel 2012; and see also chapter Visual Apprenticeship II);

the method got introduced to Italy also due to Giovanni Morelli (see Achsel 2012, p. 31),

who helped to organize a demonstration of it in 1865, carried out – in Milan – by Carl Vogt,

whom Morelli already might have met years earlier, while studying with Louis Agassiz in 1838 (see Vogt (ed.) 1847).

13) For detailed references see our survey above. (back)

14) For Pacini and for the history of the cholera in general see Briese 2003. (back)

15) While artist Ernst Fröhlich (compare also Cabinet V) had cooperated with Morelli on the 1836 Balvi magnus, which Fröhlich had also helped to inspire (see GM to Federico Frizzoni, 14 October 1836 (Anderson 1991b, p. 33f., note 32)), it appears to be unknown, by which artist the Miasma diabolicum of 1839 was provided with illustrations (such as the Kappelmeier’sche Mikroskop or the Christliche Luftvisier; for the latter see chapter Interlude II). (back)

16) See Caizzi 1958; and see again Federico 1997, p. 38f. (back)

17) Jean Paul Richter considered the year of 1856 as the year Morelli had started to collect. See Seybold 2014d, appendix. (back)

18) Since we dispose of the letters by Morelli to Mündler, it is possible to observe how the tone of Morelli speaking about business affairs does change, from being playful and rather careless to being very serious (while still being playful on the surface). See Kultzen 1989, passim. (back)

19) GM to Otto Mündler, 6 August 1864 (Kultzen 1989, p. 396). Compare also Anderson 1999a, p. 81 (for a ›good‹ cocoon harvest in 1869). (back)

20) Debts/payments: Anderson 2014, p. 65, note 44, beginning on p. 64. It might be that Morelli inherited obligations in association with mortgages. (back)

21) Federico 1997, p. 38f. (back)

22) For Layard see for example Brackman 1981 and Anderson 1987b. (back)

23) See Malli [n. d.] (Morelli within this paper being confused with his father). For Andreossi see also Anderson 1999a, p. 76; compare also the Morelli-Richter correspondence, passim (Andreossi died in 1884), and see the following important letters (I am grateful to Madeline Lennon for having made available to me her transcriptions): Austen Henry Layard to GM, 30 November 1863 [or 1864] (with Layard writing from the Foreign Office and expressing his will to do everything he could in support of Andreossi); 5 December 1864; 30 December 1864; GM to Austen Henry Layard, 8 February 1865 (speaking of ›our expedition to Japan‹). (back)

24) See again Malli [n. d.]. (back)

25) This is the view of Federico (Federico 1997, p. 38). (back)

26) See Anderson 1999a, pp. 24ff. For Morelli being (or rather pretending to be) surprised to be Melli’s heir and to inherit the collection see p. 25 (letter by Morelli to Layard, dating probably from end of February 1873). (back)

27) For Morelli wanting to resell pictures see GM to James Hudson, 12 December 1874 (Anderson 1999a, p. 29f.). Compare also p. 28 for Morelli moving to 14, Via Pontaccio, Milan. (back)

28) One has to take into consideration that for example Austen Henry Layard first heard Morelli mainly speaking about ›scientific method‹ (with speaking meaning not discussing, but rather lecturing here; compare Agosti/Manca/Panzeri (eds.) 1993, vol. 1, p. 243. (Madeline Lennon)). This must have created expectations in Layard that Morelli’s actual writings might have matched or not (with the first English translation being available only in 1883) (compare also chapters Interlude II and compare also Seybold 2014a, p. 54, note 122 (referring to Kugler/Layard [1887], p. XVI), for Layard as well as Jean Paul Richter occasionally being rather dissatisfied with Morelli remaining rather unsystematic, more envisioning a future science than implementing or sticking to scientific standards himself, and above all to the ideas of systematicity and transparency/verifiability). (back)

29) Compare Rachel Cohen 2013, p. 224f. (back)

30) Morelli, as a writer, is also to be read from the perspective of someone asking how much he did actually reveal as well as how much he actually used to keep back (compare, generally, our Giovanni Morelli Study). (back)

31) For ›expertises by Morelli‹ we can draw partly on Morelli’s actual writings, but partly, and to a significantly bigger part, we also have to draw on Morelli’s letters that actually were never meant to be published (compare, above all, the first expertise, being published for the first time here, that is: in our Cabinet III). (back)

![]()

![]()

| The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography |

(Picture: lombardiabeniculturale.it; Giacomo Ceruti detto Pitocchetto, Ritratto di fanciulla con ventaglio;

from Morelli’s own collection)

»…e i miei cari quadri, schierati tutti in bell’ordine, sorridenti e festosi nel rivedere il loro affezionato padrone e protettore. Fu, ti assicuro, un bel momento, ed io ho avuto per ognuno di essi una dolce parolina, che come tutte le belle paroline di questo mondo, fece forse maggior piacere a chi le disse che non a chi erano dirette…«

(GM to Maria Antinori, 31 May 1876 (Agosti 1985, p. 10, note 15 (beginning on p. 9)))

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH PART I:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship III

Or Go To:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | HOME

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Spending a September with Morelli at Lake Como

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | A Biographical Sketch

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Visual Apprenticeship: The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Connoisseurial Practices: The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | The Giovanni Morelli Bibliography Raisonné

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | General Bibliography

Interlude I

The commonplace that Giovanni Morelli did never practice as a doctor, basically, does match the truth. But nonetheless it is not the whole truth to say that Morelli left his medical studies behind altogether. And here we are explicitly not referring to his later connoisseurial practices, but to his giving advice when his medical advice was sought after, and to his observing what was going on in the world around him.

And in two regards he (as the world around him) had to deal with the paradoxical attempt to observe the unseen. Because the unseen (the seemingly invisible) was causing disaster. Economic desaster and also human desaster: and we are referring to the recurrent outbreaks of the cholera throughout the 19th century; and to the crisis that followed the becoming infected of European silk worm cultures with the pebrine disease. Because Giovanni Morelli got involved, in various ways, in the coming to terms with both crises; that affected him personally because like many of his friends he lived directly or indirectly on Lombardic silk production; and because people he knew became infected with the cholera.

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship III

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet I: Introduction

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet II: Questions and Answers

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet V: Digital Lermolieff

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS