M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY Interlude II: Dall’Ermo Turns Lermolieff or: Comedy, Comical Sense and Connoissseurship  |

We may imagine the visual biography of Giovanni Morelli also as the biography of a spectator, who did not only act on many stages, but joined also, and preferredly also in incognito, many audiences to watch.

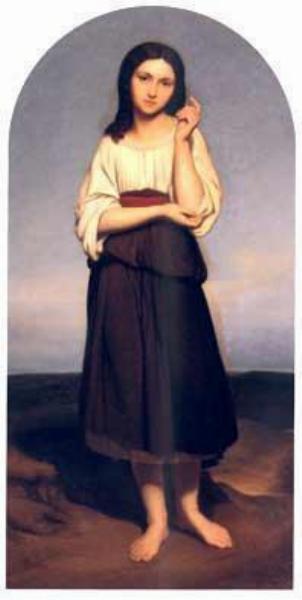

And he certainly did watch audiences as much as he did observe what was going on on stage. As a child we may imagine him having been a spectator at the Bergamo fair (the famous fiera), which, as he later did suggest once, he did not much like. But still we may follow the various kinds of stages that played a role in his life. Because he played a role on them (or preferred to watch audiences and actors from inside the crowd). (On the right a figure of the Bergamo teatro dei burattini: Pacì Paciana, a brigand; picture: Giorces).

ONE) LIFE AS A COMEDY

INTERLUDE II:

(ONE) LIFE AS A COMEDY

(TWO) A SECRET CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ REVEALED

(THREE) ENTER LERMOLIEFF![]()

21-year-old Giovanni Morelli as drawn

by Bonaventura Genelli in 1837

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 114)

›[…] and these circles of high society, besides that, where one does have to play a boring role in an even more boring comedy, have come to be anathema to me in the extreme. One’s better self one cannot render, and one must not, and one doesn’t want to, and the rest only someone might like who, himself, is nothing but a stuffed skin, lacking all flesh and all blood. […].

Here, judged neutrally and without prejudice, it is all about the exterior pretence; the dew of human emotion is being plucked and twitched to Charpie, and everything is brought to the boil – this, at least, I have found in all circles, except in the better ones. But where would’t one find this?‹

»[…] & abgesehen von dem, sind mir diese hohen Zirkel, wo man eine langweilige Rolle in der noch langweiligeren Komödie spielen muss, im höchsten Grade verhasst geworden. Sein besseres Ich kann u darf man nicht geben u mag es auch nicht, u an dem übrigen kann nur der Gefallen finden, der selbst nur ein ausgestopfter Balg ist u dem alles Fleisch u alles Blut abgeht. […].

Hier geht doch, unparteiisch u vorurteilsfrei geurteilt, fast alles nur auf den äusseren Schein aus; der Tau des menschlichen Gefühls wird hier zu Charpie gerupft u gezupft u alles auf die Spitze getrieben – dies hab’ ich wenigstens fast in allen Zirkeln, die besseren ausgenommen, gefunden. Dch wo wäre dieses nicht zu finden?«

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 14 June 1838; from Berlin)

›HE LOVED TO MAKE FUN AND TO DISGUISE‹

The Giovanni Morelli Collection IV: mirroring a comedian’s and satirist’s mentality

Rissa di contadini – a ›peasants’ brawl‹, by Hieronymus Bosch (manner of),

and from Morelli’s own collection

(picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

Giovanni Morelli could see life as a comedy, which is obvious because he could show life as comedy. Many of his letters make the impression, in unfolding large burlesque scenarios and telling of quixotic adventures,(1) that life was all comedy to him, but this was not the case. In fact we have to distinguish various types of comedy to come closer to what comedy and human comedy meant to him.

Giovanni Morelli did use the very notion of ›comedy‹ repeatedly, as in the above given quote, to designate human social life as such, but very significantly and also more specifically: to designate experiences that were going beyond a joke.(2)

This double meaning, the traditional referring to human life in terms of a stage, and to the suddenly turning of everyday scenarios into unpleasant scenarios, is at the origin of Giovanni Morelli developing a sense of comedy and the wish to reflect human comedy in terms of comedy, and this obviously beyond his love of fun that was being part of his nature. Comedy, as elaborated in prose writing, or in more dialogical writing, or even in comedy, to be represented on stage, was not meant simply to entertain and to respond to someone else’s love of fun, but to reflect about, to deal with the comedy of life, using appropriate means.

To the latter, however, it never did come in Giovanni Morelli’s life, although – we will come to this – at several occasions he seemed to be near to turn himself into an actual playwright, who was to renew – this was the outspoken ideal – the Italian theatre, in terms of giving Italy a good, new, contemporary comedy that was also to foster patriotism, and certainly was also to be an expression of Morelli’s own political ideas and ideals, especially after 1848/49.(3)

But at the origins of Giovanni Morelli’s rather secretive career as a writer was naturally also his general sense of comedy, that is: his comedic sense, being part of his nature, fit to exploit situations, events, people’s appearances, like one could also do in letters, in terms of comedy. In terms of funny descriptions, and in terms of elaborating comical ideas or comical effect playfully, and also, and not the least, in terms of practical jokes.(4)

Prometheus with Echo, echoing Prometheus’ clamour (painting version):

Genelli’s letters to Morelli imply that the latter had not seen the

Prometheus drawing before (compare Bonaventura Genelli to GM,

29 August; 28 October; 11 December 1854)

Tradition, for example, has transmitted that, allegedly, the sitter or model for Bonaventura Genelli’s Prometheus had been Giovanni Morelli. While, in fact, when Genelli informed Morelli about having worked out a respective drawing, he did not seem to remember any connection between the alleged sitter and the motif.(5)

Rather it does seem that Morelli, who attempted to support Genelli in that he tried to find collectors wanting to buy works by Genelli, attempted to have a certain lady from Milan buy drawings by Genelli. Which seems also to be the context of his suggesting – or pretending – of having been the sitter for the rendering of this particularly athletic Prometheus. Knowing or assuming already at that time that artists were in the habit of imposing their inner notions of anatomy on representations of real people (Morelli in fact had been portrayed by Genelli); and why shouldn’t one elaborate on the very idea also ficticiously and frivolously?

Hence: What we seem to face here is simply one origin of the later so-called Morellian method: an ability to reflect upon the artist’s mind, expressing itself in form – and also the comical effect resulting from just frivolously pretending that, in a particular case, the artist had imposed his athletic notions of anatomy on the actual (and also athletic) body of someone who, already for quite some time, had lived, away from the artist, in Italy, and, in all probabiliy, had not been the sitter at all. But had liked to pretend just that – and perhaps also to the before mentioned, but unknown Milanese lady.

At a soirée with Ludwig Tieck reading aloud at Dresden in 1838

Giovanni Morelli had suggested, to test him, that Tieck should

read the Alcestis by Euripides (and he also heard him read

Shakespeare, Kleist and not the least: Goldoni)

(picture: gutenberg.spiegel.de)

How avid a reader of comedies young Giovanni Morelli has been, can easily be demonstrated just by naming what he read. But he seems to have read everything, from Macchiavelli to Molière; from Goldoni, of course (whom he heard also being recited by Ludwig Tieck, as he heard comedies by Heinrich von Kleist being recited), to Ludvig Holberg.(6) And instead of enlisting every comedy that Giovanni Morelli ever read here, we may also point to the fact that among his books, later, was to be found the ›History of comical literature‹ by Karl Friedrich Flögel (as well as the ›History of the court jesters‹ by the same author), a summary, an actual summa of comedy, that provides its reader also with something rather unexpected: because the book, displaying overwhelming pedantry, does read extraordinarily funny, because of its being written that pedantically.(7)

This, certainly, was something according to Giovanni Morelli’s taste, who, above all, found human pretensions of all kinds something to be ridiculed.(8) Something to be satirized. Or to be mocked within actual comedy.

The more serious background of this all might also have been that the life of Giovanni Morelli also showed to be, occasionally, but not actually rarely, to be a book of comedy. That is: his life, his biography was producing comedy, and not always to his liking.

This was due, on the one hand, to his all-sided receptiveness and wide intellectual horizon, but on the other hand due to the fact that the conventional roles that life provided for someone like him, someone displaying all-sided receptiveness, were mainly roles that could not fit. Not to mention his scepticism that made him question again everything he seemed to have attained.

One might, again, enlist the situations, that showed Morelli as a doctor of medicine (being rather inclined to make fun of foolish doctors and foolish medicine);(9) or situations that showed him thinking whether he should become a professor (being rather inclined to make fun of professors, especially of German professors);(10) or situations that showed him as a diplomat (hardly being able to control his temper, and besides that rather inclined to mock certain other diplomats, he had observed in Paris).(11)

And as we will see Giovanni Morelli turned out to be a connoisseur of art who, still, did not refer to this activity as to his actual profession, his métier, remaining inclined, as we will see as well, to observe the great comedy of connoisseurship that he, that life was to produce with him, rather at the end of his life (and with him, occasionally, disliking what he was doing, what he, himself, had chosen to do).(12)

For the moment, however, it seems appropriate to begin a review of the career of Giovanni Morelli, man of letters, with a discussion of his earliest attempts to write comedy, or here: with life producing, seemingly, comedy, but not always a comedy to his liking, with him.

*

THE CARL BLECHEN AFFAIR

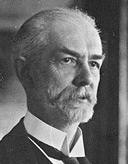

Carl Blechen (1798-1840)

At least two times in his life Giovanni Morelli was confronted with the phenomena of mental illness. This subject, certainly, does not appear as the most able subject to deal with in terms of a comedy. Moritz Thausing, the professor at Vienna, who was not only a dear friend of Morelli but had also encouraged him to write on connoisseurial matters, was to become mentally ill during the 1880s.(13) And Morelli had not the slightest reason to deal with this fact in terms of a comedy. In fact he was to try to be of help as best as he could, he was to speak with doctors, he was to correspond with Thausing’s pupils, and he was to worry about Thausing’s family.

This had been somewhat different when, as a very young man and more than forty years earlier, Morelli had been confronted with the phenomena of mental illness for the very first time. For the very first time in real life – because even earlier, in 1836, he had found the inspiration for his first satirical piece in a comment by Guido Görres on the Narrenhaus by Wilhelm Kaulbach, a picture that had dealt, as a work of art, with the phenomena of mental illness and with the inhabitants of a madhouse.(14)

But this hardly could be seen as something preparing for what 22-year-old Morelli experienced, in 1838, when he got involved in – and to some degree also got responsible for what evolved as, and what we should like to call here – the Carl Blechen affair. Which refers to the well-meaning, if rather chaotic and in the end failing attempts to organize help for painter Carl Blechen who had become mentally instable and seemed to be in need of help.(15)

As the driving force behind these attempts the Berlin-based writer Bettina von Arnim has to be named, but the role of Morelli, according to his own account, was a rather active one – with him stimulating and inspiring the actions of Bettina von Arnim. And all of a sudden young Morelli had found himself being part of something that he tried to deal with in terms of a comedy. But even though his accounts are certainly not lacking a burlesque element, this attempt did also fail. And what happened, in hindsight, does read as a rather tragic story (and not even as a tragicomedy).

In the end Morelli had also been rather fortunate to have escaped (with the indirect help of his mother) from Berlin. And in some sense he had also been lucky to have been able to escape from Bettina. Bettina that he actually had liked as well, but that also had tended to monopolize him, and this was something he did not like at all.(16)

He got away and did escape from something that has not remained unknown to history, although a complete history of that affair has never been attempted. If though novelist Theodor Fontane had actually realized his plan to write a full biography of Carl Blechen, he might, when researching the events of 1838,(17) actually have wondered who this young student named Morell had been. Who obviously had been a part of these strange events. And had also played a rather active role therein. Who, as one may also say, had fled.

And who, which yet had remained unknown to Fontane, had also been attempting to deal with these events in terms of a comedy, that he did write letters that partly read like the description of a comedy. Something that he actually did only once. In other words: he was not to do it again, and later, he was probably far from doing such thing again.

The Stuttgart version of Bathers in Terni Park by Carl Blechen that

Bettina von Arnim had bought and destined to be the prize of a lottery

to the benefit of the painter who had fallen mentally ill. Also Morelli

did buy a lot, but did not win the picture.

Bettina von Arnim (1785-1859),

drawn by Ludwig Grimm on 28 November 1838,

that is: only months after Morelli left Berlin

(see Böttger 1987, p. 415)

Giovanni Morelli had come to make the acquaintance of writer Bettina von Arnim at a time that her then protegé Philipp Nathusius was abroad, travelling in Italy.(18) This is, in a certain sense, important to know, since Giovanni Morelli was about to enter one particular chapter of writer Bettina von Arnim’s biography, and this was the chapter of her special relationship with young people, with students, with men – like Giovanni Morelli – that Bettina perceived as being stimulating to her, but also as protegés to be guided, educated and even formed.(19) Had Giovanni Morelli stayed longer, maybe a book like Bettina’s Ilius Pamphilius und die Ambrosia had been the outcome, another one the one hand documentary, but on the other hand literary work into which Bettina von Arnim turned her correspondences and relationships with various people, another work that resulted from relationships like the one that was unfolding with young Morell.

But 22-year-old Morelli was not to stay longer, and from the beginning he was rather the one, at least according to his own accounts, to study, that is to observe Bettina, to question her about her brother Clemens or about other people (like for example Friedrich Schleiermacher).(20)

He did also make the acquaintance with two of her daughters,(21) and if he ever revealed that he was writing too, we do not know. It seems that he was seen by Bettina primarily as an Italian (the Brentano family had its roots at the shores of Lake Como), and also as a student, as a doctor, and as someone who was to enlighten her as to the natural sciences.(22)

Beside that Morelli was simply funny, charming and intelligent. Someone one liked to spend time with, to make fun and to amuse oneself. Which, all in all, was certainly a scenario not without comical potential, since, it is known to Bettina’s biographers, she was also very dedicated to what, in hindsight, the history of medicine is used to call the romantic medicine (as opposed to what, certainly also Morelli, regarded as the more serious natural sciences), and Morelli was to exploit her interests, and her ways to deal with doctors, for example, also to comical effect in his letters.(23)

Maximiliane and Armgart

von Arnim in 1837

(picture: petrihaus-frankfurt.de)

After now having been associating with Bettina von Arnim and her daughters for a while, Morelli had gotten to know also that Bettina had started efforts to support, to help and in some sense also ›rescue‹ painter Carl Blechen, who had fallen mentally ill. And while to Morelli this might have seemed as the natural progressing of his associating with Bettina, he got involved into these efforts, got to know the other people involved, restorer Xeller, and a picture dealer named Sachse, and also made his own suggestions.(24)

As to the diagnosis, after he had gotten to know also Blechen and his wife, a medical, or rather: psychological diagnosis concerning the Blechen case. And as to what could possibly be done.

Morelli and Bettina seem to have agreed that, in some sense, Blechen had to be ›rescued‹ from his wife, his marriage, his miserable life, since it was assumed that he was tyrannized by his wife which is described also as being particularly ugly.(25) And, not even very subliminally, this matter was also about the intimate life of Blechen and his wife, in a surprisingly frank way discussed between the young Morelli and the 53-year-old Bettina von Arnim.(26)

It does even seem, judging from Morelli’s account, that he was actually the one who in a certain sense diagnosed what was wrong with Blechen, and he suggested, to apparently great amusement, that he, Morelli, was, if Blechen was not allowed to make a journey, away from his ›house dragon‹, to Dresden and subsequently to Bad Gastein, to get better at another place, that it would be him – to abduct Blechen from his wife.(27)

It did not come to this. And instead something evolved that rather reads as a complete chaos; and after a while Morelli seems also to have enough of this chaos, of his associating with a very interesting but also monopolizing woman as was Bettina von Arnim. And since his mother had written to him that he was to stay in Switzerland with her for a month, before he was, as planned, going to Paris for a longer time, Morelli found a way to escape from the affair Blechen, that, in the following, he was to report, in a series of letters, partly from Paris, to his Munich friend Genelli.

At the beginning of the Blechen affair had been a noble cause: the wish to help painter Carl Blechen to get better. At the end of the Blechen affair, or at least some time after the efforts of Bettina von Arnim to ›rescue Blechen‹ had come to an end, had been Blechen’s death in 1840. After he had travelled once more with his wife (to Jüterbog); but, as a matter of fact, he had not gotten better.(28)

It is certainly difficult, if not impossible, to assess – in a fair fay – the specific roles of those who had been active, who had been involved or embroiled into that affair – and Giovanni Morelli had been one of the persons involved –, but at least it should be said that for example to novelist Theodor Fontane, that it did seem that the noble cause was rather, or also represented by Carl Blechen’s wife who, by Bettina von Arnim as well as by Giovanni Morelli had been seen as being the cause, or one of the causes of Blechen’s illness.(29)

In hindsight it does not seem to be simple at all, if these story had to be written in terms of a comedy, to actually decide about who had to be ridiculed in this story; but – to be fair – it had not seemed, at the day, to Giovanni Morelli to be that simple either. Because he had, partly, ridiculed, in his accounts, also Bettina von Arnims efforts, next to several doctor’s efforts and next to Blechen’s wife, the actual or seeming center of the whole affair.

But since he had also been stimulating Bettina’s efforts, he did, if indirectly, also ridicule himself, and the attempt to exploit something for comical effect that actually – he could not know it – was to end tragically and sadly, and certainly does not read as a comedy in hindsight.

Blechen could not be helped; and he was to die in 1840, two years after the affair that, within the biography of Bettina von Arnim, does figure only as an episode.(30) While it does figure in Giovanni Morelli’s accounts as a quixotic and chaotic panorama, with him, by accident, finding a door to leave, after been active in something that rather got out of hand.

And how the affair was seen by Blechen’s wife – to whom at least novelist Theodor Fontane has attempted to do justice – one does not actually know.

*

FROM PROSE TO DIALOGICAL WRITING

Joseph Görres (1776-1848)

Guido Görres (1805-1852)

At Munich Giovanni Morelli had frequented the theatre,(31) but only at Paris, where he had arrived in the fall of 1838, to stay for almost two years, he turned to actually write comedy. This happened also via his turning to write prose in a more dialogical style; and one issue, after he had dealt with art history and with his Munich lunch club in 1836 and in his first literary piece, was primarily on his mind: and this was the whole complex that was, at the day, to be associated with political Catholicism, the Munich romantic Catholicism, or, if one was inclined to have it that way: militant Catholic propaganda.(32)

And Giovanni Morelli, although not at all a militant Protestant, rather on the contrary (at least in a certain sense, since the religious question as such meant an embarrassment to him throughout his life),(33) was in fact enraged. For a special reason. And to understand that special reason, today some historical explanations are necessary, not the least to understand what stimulated Giovanni Morelli to write and, in writing, to satirize manifestations of political Catholicism.

While painter Wilhelm von Kaulbach had chosen

to depict the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (picture: bilder-geschichte.de),

Morelli – probably also inspired by such designs,

since he had known the Hunnenschlacht cartoon – chose to satirize

the Catholic Görres-circle with his epic poem

›Die Schlacht auf dem Lechfeld‹, also called ›Die Sage von den drei Schwestern‹

(compare GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 24 April 1839);

using another battle (the Battle of Lechfeld) as his setting,

to render, as he also told Genelli,

personalities like Joseph and Guido Görres,

Johann Nepomuk von Ringseis, Ignaz Döllinger (the younger),

the late Johann Adam Möhler, George Philipps, Kraft Karl Ernst Moy de Sens,

Heinrich Leo and, possibly, Friedrich August Strubberg (›Struberg‹);

the poem, however, that Morelli allowed Genelli to keep,

after he had been advised rather not to publish it

(see Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 7 March 1840),

seems not to be extant.

But above all it is necessary to understand that among Munich friends and acquaintances, in Munich circles Morelli had been seen as an Italian, and that, obviously, one had taken for granted that this also meant that Morell was a Catholic.(34) And we understand that also here, the role of the Italian was to Morelli’s liking, and he was identifying with that role, only that the conventional role of an Italian Catholic did not quite fit. And Giovanni Morelli had obviously also remained silent as to this slight, but complicated ambiguity.

But now something had happened: the Prussian state and the Catholic church were in conflict over the question of how to deal with confessionally mixed marriages; and the archbishof of Cologne, due to his stance in the matter, even had been arrested on 20 November 1837.(35) This again had mobilized what one was to call the Catholic propaganda, namely professor, writer and publicist Joseph Görres at Munich, whom Morelli knew (as well as he knew the son of Görres, Guido, who was frequenting writer Clemens Brentano, as also Morelli had).

And in 1838 Joseph Görres had published a pamphlet named Athanasius, wherein he had referred to the children of confessionally mixed marriages as ›hybrid bastards‹ (›zweischlächtige Bastarde‹).

And this particular expression had particularly and terribly enraged Morelli, since a cousin of his might have been a child from a confessionally mixed marriage;(36) and certainly he was to some degree informed as to the matter of the so-called Kölner Wirren, when, in 1839, at Paris, suddenly acquaintances from Munich showed up, obviously not knowing of Morelli’s more complicated identity, nor of his being enraged.

Because these acquaintances were simply assuming that he, dear Morell from Munich, was certainly on their Catholic side. But far from that.

And here, within the scenery of that conflict, Morelli was even, for once, openly declaring that he was a Protestant. Which, on the other hand, was not actually the full truth, since he only did declare to be Protestant to shock these acquaintances from Munich, allies of Görres, who had dared to insult his dear cousin. In sum: for tactical reasons.

First it was Guido Görres, dropping in at Morelli’s Paris flat, with Morelli becoming enraged to the degree that he almost felt to provoke Guido to a duel, by writing a provocative letter (that he did also cite, in full, in a letter to Genelli,(37) when his scepticism already had dulled a little his hotheaded temper).

It did, however, not come to that (that Morelli was defending the honor of his cousin, in duelling himself with Guido Görres), but only a little later another Munich acquaintance showed up, that Morelli only does refer to as the ›Canaille‹ (probably to be identified with Franz Xaver Reithmayr). When displaying the scene that had unfolded, again in his flat, in a letter to Genelli.

And it was here, at this point, that he turned from writing prose, to virtually writing of only dialogue, to show, and probably also to already satirize the scene, for Genelli.

›Canaille: Don’t you know me anymore, Herr Doctor; we have repeatedly seen us in Munich, if I am not mistaken, at Herrn Brentano’s place?

Me: I don’t seem to be able to recall.

Canaille (smiling): Yes, yes, this happens – one does forget us theologians soon.

Me: So you are a theologian, then?

Canaille: Yes, indeed, yes indeed; (Canaille taking a seat, without me having invited him) now when do you wish to return to our dear Bavaria?

Me: For the moment I have no business to attend there.

Canaille: You must be attached even more to our Munich, as an Italian & hence a real Catholic, due to the last affairs.

Me: I am, if you permit, a Protestant.

Canaille (opens wide his eyes): Well, well, that is: Christ, let’s prefer to say Christ.

Me: No, let’s say Protestant.

Canaille: But why then Protestant?

Me: Because it is to my liking.

Canaille (stands up & paces the room): Do you know also Herrn Görres? – it seems to me that I might have seen you at his place – his son is here.

Me: That rascal I do know only too well & and if his son is here or not, I do not care – I have nothing to do with these people.

Canaille (grasps his umbrella): You seem to be fast in judging a man & probably have not read the Athanasius?

Me: I have better things to do than to read stuff and nonsense of that kind.

Canaille: Well yes, there we have another example. Excuse me, I have now to go to our ambassador. I am taking my leave.‹

·················································································································································································································

»Canaille: Kennen sie mich nicht mehr, Herr Doctor; wir haben uns öfter in München gesehen, wenn ich nicht irre, bei Herrn Brentano?

Ich: Ich mag mich dessen nicht erinnern.

Canaille/läch[elt]: Ja, ja, so gehts – uns Theologen vergisst man bald.

Ich: So sind sie Theologe?

Canaille: Ja freilich, ja freilich; (sie setzt sich, ohne dass ich sie geheissen) nun wann wollen sie wieder in unser liebes Bayern kommen?

Ich: Vorderhand hab ich nichts da zu tun.

Canaille: Unser München muss Ihnen, als Italiener & folglich echtem Katholiken, durch die letzten Affären noch lieber worden sein.

Ich: Ich bin, wenn sie erlauben, Protestant.

Canaille (reisst d. Augen auf): Nun ja, also Christ, sagen wir lieber Christ.

Ich: Nein, sagen wir Protestant.

Canaille: Warum denn Protestant allein?

Ich: Weil’s mich so freut.

Canaille (sie steht auf & geht im Zimmer auf & ab): Kennen sie auch den Herrn Görres? – ich glaube, ich hätte Sie bei ihm gesehen – sein Sohn ist hier.

Ich: Jenen Schuft kenne ich nur zu gut & ob sein Sohn hier sei oder nicht, das ist mir gleich – ich habe mit diesen Leuten nichts zu schaffen.

Canaille (nimmt ihr Parapluie in d. Hand): Sie fällen schnell ein Urteil über [einen] Menschen & haben wohl den Athanasius nicht gelesen?

Ich: Ich habe besseres zu tun, als dergleichen Gewäsch zu lesen.

Canaille: Nun ja, da haben wir’s wieder ein Beispiel. Verzeihen sie, ich muss nun zum Gesandten gehen. Ich empfehl’ mich.«(38)

We can see here, not only how Morelli was turning to write actual dialogical scenes, but also how something serious was at the origins of his wanting to write, and particularly to write comedy. Two things actually, because on the one hand it was about the Catholic propaganda, seeking for possible allies at Paris. And on the other hand about the serious backdrop of Morelli’s complicated identity, and particularly about his not being willing, more than necessary, to reveal his innermost thoughts.

Because here, while he had obviously avoided to discuss the matter at Munich, the comedy of life made him reveal his Protestant origins, although, just here, with Morelli revealing, he was taking a stance, a seemingly firm stance, that was not his actual stance in the matter, and that only he took, here and ostentatiously, to shock the Catholic side, respectively the character he named the ›Canaille‹.

And it was Giovanni Morelli who did write, who did produce this comedy, but it was also and again his life with and in a complicated identity, with roles usually not quite fitting, that also contributed to the writing of this particular comedy.

Figures from Giovanni Morelli’s satire Das Miasma diabolicum (Morelli 1839); on top the adult version of the so-called ›christliches Luftvisier‹ (›Christian air-ventail; to be used against, that is: to filter any un-Christian miasms); below the version for children (source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a)

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND THE CARICATURE

Martin Disteli’s illustration to the fable Der Sumpfreigen by Abraham Emanuel Fröhlich

Ernst Fröhlich, Grosse Toilette von A. Mende

(source: Giovanni Morelli, Balvi magnus und

Das Miasma diabolicum, ed. by Jaynie Anderson,

Würzburg 1991, p. 80)

A caricature, once owned by Gustavo Frizzoni, and attributed to Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

(source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 334; see also p. 228)

Abraham Emanuel Fröhlich

1826-1832: Abraham Emanuel Fröhlich, Morelli’s teacher of German and of religious instruction at Aarau, is not only to be considered as an early literary influence on Morelli, but as a model of a writer cooperating with an illustrator (see picture on the left).

1832-1837: from Morelli’s Munich period a rather large body of drawings, illustrations, caricatures had remained which partly have to do or are to be associated with his own literary ambition (see Anderson/Morelli 1991a); some remaining drawings show also Morelli and/or Munich friends of his (on the left a caricature of another of Morelli’s friends, the painter Carl Adolph Mende);

the Balvi magnus of 1836 as the Miasma diabolicum of 1839 comprised also visual, and particularly caricatural components; Genelli and Morelli, however, did never cooperate artistically, in spite of Morelli’s wish to have Genelli draw Schneck, one of the characters that Morelli did invent; and in spite of Genelli wishing Morelli to contribute in writing to his cycle Aus dem Leben eines Wüstlings; for Morelli mentioning Hogarth and Chodowiecki see GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 26 February 1838.

Kaspar Braun

1839: in Paris Morelli meets with painter/wood engraver Johann Rehle and wood engraver Kaspar Braun; the latter, in the years to come, being the editor of the famous weekly Fliegende Blätter and also the editor of Wilhelm Busch.

1840: Genelli describes, in a letter to Morelli (7 March), the caricature of a philosopher and a monk disputing.

1845: Engelhardt and Morelli, in comparing the writers Alessandro Manzoni and Giovanni Battista Niccolini, dwell on various types of satire (see Engelhardt/Morelli 1845a, p. 2018; quoted in chapter Visual Apprenticeship I)

1889: Morelli wishes drawings of characteristic artist’s marks, which are meant to illustrate his books, being drawn ›somewhat caricatured‹ (»etwas karikiert«), and this for the better understanding of the laymen (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 5 February 1889).

**

TWO) A SECRET CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ REVEALED

SENT FROM PARIS

Eduard Devrient (1801-1877)

Also from the ›Salon of 1839‹ – François-Auguste Biard, Fight with Polar Bears

(compare Devrient 1840, p. 14)

For someone wanting to know more about the Paris of 1839 – the Paris of 23-year-old Giovanni Morelli, as we may also say – there is no better choice than to consult the ›Letters from Paris‹ that the great actor, playwright, theatre reformer etc. Eduard Devrient sent from Paris in 1839, to his wife and also to posterity, since Devrient subsequently decided to publish these letters also as a book.(39)

These letters do not only give us an impression of how Paris of 1839 looked like, with its gaz lights and omnibuses, with its more or less faint memories of the revolutions of 1830 and of 1789ff. (bullet holes; songs; the Obelisk on Place de la Concorde, next to which two fountains were under construction), with its elegants (being apparently dedicated to milk rice with sugar and orange water, served in a silver bowl) and showing, as elegants, long beards, as such beards were, that year, considered as being fashionable.(40)

But these letters, naturally, do give us an impression of how Paris, in 1839, looked like, if seen by someone being dedicated, passionately dedicated, to the theatre in all its diverse manifestations, and also being passionate as to the other forms of art.

Devrient visited Paris in the spring of 1839, and he naturally and primarily did visit the various stages, but also the Italian opera (where he did see a memorable performance with Giulia Grisi, whom he described as a most accomplished artist and singer), the Louvre (with the ›Salon of 1839‹), and also the various salons, meeting with the leading writers and playwrights of the day, like for example Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo.(41)

This setting was, all in all, not only the setting of Giovanni Morelli turning from writing prose and epic prose to writing prose in an almost drama-like, that is, in dialogical form, but also the setting of Giovanni Morelli, finishing his first comedy, entitled Kunstkenner (›Connoisseurs of Art‹, or ›Connoisseur of Art‹, but the plural, here, seems to be more adequate).

One might think that the background of Paris, seen by someone being passionately dedicated to the theatre, as also Morelli was, did primarily influence Morelli to his making of this step.

But it is striking as well, that Morelli seemed to have needed the distance of Paris, to look back upon the experiences that he had made in Munich, Erlangen and particularly at Berlin, where he had accumulated those experiences and gathered those observations that he was now to work into this one, into his first actual play. And naturally this play might also have been inspired by Morelli observing Parisian connoisseurs of art, or by his studying of art with other connoisseurs.

Might, because the full text of that significant play Kunstkenner, without any doubt very telling as to young Giovanni Morelli’s perception of art connoisseurship in 1839, seems not to be available (if it is extant), or it is simply not extant.

But without any doubt, since Morelli’s friends Bonaventura Genelli and Carl Adolph Mende got to read that play, and we at least do know what Genelli wrote back to Morelli concerning that play, and we do know how much Genelli had liked that play, and that Mende also had appreciated that play as well.

That 23-year-old Morelli had sent to Genelli. From Paris.(42)

A 1826 view of Place de la Concorde (then Place Louis XVI)

by Giuseppe Canella

A view of 1840

The (once) existence of Giovanni Morelli’s comedy Kunstkenner presents us with the interesting problem to reconstruct a comedy about connoisseurs of art, with artists being among them, just on basis of what two artists have said, who had the chance to actually read that comedy, and who, not the least, did state, apparently with satisfaction, that the two painters within that play were actually to be considered and to be named as the only two reasonable characters within that play.(43)

In short: the comedy was meant to ridicule foolish connoisseurs of art and foolish connoisseurship, represented by, above all, two male connoisseurs named Presskopf and Trommelfell (›Mr. Brawn‹ and ›Mr. Eardrum‹), and probably also by their wives.

But not without also giving or showing a backdrop of reasonable, of real art connoisseurship, represented here by two painters.

The painters were occasionally also meant to sing;(44) Morelli had adapted an anecdote that Genelli once had told him, about connoisseurs ›sharing‹ a drawing by Giulio Romano; there was also a scene with an urn, and the whole plot was, as Genelli said, invented splendily; and last but not least: as Morelli himself had already told Genelli – the first act was, as it were and due to the language used – ›stinking somewhat of beer‹ (it is about juvenilia by Morelli here).(45)

All in all it was a play that was very well received by its fortunate two readers. Only that our two readers – Bonaventura Genelli and Carl Adolph Mende – did also agree that, what these two painters were saying within that play was reasonable enough to have them identified as the only two reasonable figures within that play, but that these two real connoisseurs – in their opinion – were still a little short of being real ingenious connoisseurs of art.(46)

In other words: one was to expect a little more. A little more ingenuity. And also, or particularly from Morelli.

And yet: young Giovanni Morelli had shown himself able to invent or to show real connoisseurs of art in a play. Even if these characters were still lacking actual genius, which was an indirect way of saying that, also the mind of the creator of these characters had still to develop also to become a real connoisseur of art. Because, as we may assume, only someone also being able to display real art connoisseurship himself in real life, could also be able to display such connoisseurship, such real expertise indirectly: by having it shown by characters on stage, with such characters being opposed to foolish connoisseurs (that to invent seemed to be less demanding).

Genelli, at least, was upbeat in that he advised Morelli, even begged and demanded, that his young friend should develop that subject matter further. In the artist’s own words:

›Now my request! Don’t give up this play, laid out that fortunately in regard to the most fortunate subject matter that, for our day, certainly is the most interesting in regard to a comedy – but do cultivate it mercilessly, even if, in doing that, several years should pass. I believe that this subject is, as it were, tailor-made for you, since this you have already proven, and do cultivate it con amore and it will be received con applauso! Certainly it is yet an advantage to have found such a subject matter, worth to practice oneself, with all forces, on it.‹

·························································································································································································································

»Nun meine Bitte! Geben Sie dies auf den glücklichsten, für unsere Zeit gewiss interessantesten Stoff zu einer Komödie so glücklich angelegte Stück nicht auf – sondern kultivieren Sie es bis aufs Letzte, sollten auch einige Jahre darüber vergehn. Ich glaube dieser Gegenstand ist wie für Sie gemacht, denn dies haben Sie bereits bewiesen, und kultivieren Sie ihn con amore u er wird con applauso aufgenommen werden! Gewiss ist es schon ein Vorteil, einen solchen Stoff gefunden zu haben, an dem es der Mühe wert ist, sich mit allen Kräften zu üben.«(47)

*

›TO GIVE ITALY A GOOD COMEDY‹

To Paolo Veronese, in Morelli’s youth one of his preferred artists,

Morelli was later to refer to as to a ›poet writing comedies‹ (»Komödiendichter«; Morelli 1891, p. 329);

given here a detail of The Adoration of the Virgin by the Coccina Family

›The comical theatre of Italy [the comical genre in the Italian dramatic art; or ›the Italian comedy‹] did originate at a time when, by Lorenzo de’ Medici, the study of the ancients had been revived and by the next consequences of this revival the individual development of the national mind had been damaged in the extreme. The few specifically Italian attempts in the comical genre of the dramatic art, as the Mandragola by Macchiavelli, were being dismissed soon by the later grammarians and academicians and doomed to oblivion. Who did write comedies had to write them according to the models of Plautus and Terence. Of course no national theatre, thus, could originate. Finally Goldoni appeared, sticked to Molière and laid the fundament to the comical theatre of Italy.‹

»Das komische Theater Italiens hat sich zu einer Zeit gebildet, da durch Lorenzo von Medici das Studium der Alten in Italien wieder ins Leben gerufen und durch die nächsten Folgen dieser Erweckung der eigentümlichen Entwicklung des nationalen Geistes der grösste Schaden zugefügt worden war. Die wenigen eigentümlich italienischen Versuche in komischer Dramatik, wie die Mandragola des Macchiavelli, wurden bald durch die spätern Grammatiker und Akademiker verworfen und zur Vergessenheit verdammt. Wer Komödien schrieb, musste sie nach den Mustern des Plautus und des Terentius schreiben. Natürlich konnte sich also kein nationales Theater bilden. Endlich trat Goldoni auf, hielt sich an Molière und legte den Grund zu dem komischen Theater Italiens.«

(Source: Engelhardt/Morelli 1845a, p. 2026)

Was one to make fun with the great, with the quintessential Italian painters of the Renaissance? This is a question that Giovanni Morelli might have asked himself (but he did also observe that for example Paolo Veronese seemed to be, on his part, a ›poet writing comedies‹ himself).(48)

While staying in Rome Morelli might have pondered that question, and while discovering the great, the quintessential painters of the Renaissance (that were also to outshadow, to a large degree, his early enthusiasm for Veronese).

And with the eyes of Carl Friedrich von Rumohr he did see them, or at least: the one great painter Raphael. Because it is obvious that Morelli had read Rumohr. And it does also seem that with one of his next dramatic projects, he was to adapt a particular observation made by Rumohr.(49)

Who had been observing that painters, apparently, were in the habit of imposing their will on all subjects that they did paint. Resulting with, for example, Michelangelo being always monumental, even if he had to render delicate things. And only Raphael was to be regarded as the one exception. Because Raphael, the objectively observing Raphael, knew always to apply the most adequate artistic means. Adequate regarding his subjects: and if delicacy was needed, Raphael was delicate (but he could also be monumental, if a subject was requiring the painter to use monumental means and to unfold monumental prospects).

Madonna con Bambino e San Girolamo by Alessandro Bonvicino detto Moretto (bottega),

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

This idea might have been the basic idea to the play Gli Artisti that Giovanni Morelli had wanted to pen down in Rome, when it was advisable, due to the Roman summer heat, rather to stay inside, in a cool chamber, and not to keep on making excursions to the Campagna Romana or to simply stroll through the Eternal City.(50)

But it remains unknown what Giovanni Morelli – turning, as to subject matter, from the connoisseurs of art to the artists – exactly had in mind.

Maybe himself, in the end, might also have found, that it perhaps was not advisable to introduce himself as a playwright making fun of the great artists.(51) Although also later, the idea of artists imposing their nature upon form, remained, after he had turned to be a connoisseur of art himself, a crucial idea (not the idea of artists imposing their deliberate will, though, but the idea that artists – deliberately-unvoluntarily – imposed inner ideas of form upon form rendered). With Giovanni Morelli introducing positivism into art connoisseurship, and with Giovanni Morelli, perhaps, again asking (as we will see), if it was advisable, or to what degree advisable, to make fun of as serious an idea as positivism.(52)

Because his urge to make fun with something was to stay always with him, in early days as in his old age, and if more to the benefit or to the disadvantage of his later scientific output, remains open to be questioned.(53)

Something that, however, can be observed even in his Sturm und Drang days, when he penned down his play Kunstkenner, and apparently also a play named Kilian vom Teich oder das mephistophelische Genie (probably influenced by early Goethe Sturm und Drang plays),(54) and this very characteristic phenomena was a mix of Sturm und Drang urge to express his own feelings and thoughs with verve, but also a reluctance, that probably was an early expression of his innate scepticism that, from time to time, dulled his own enthusiasm. That he had for his own Sturm und Drang enterprises, and as to an all too full of verve style to express himself, and to appear on the scene.

Because this might have been the next step that he was going to envision and to take: to read aloud his plays to others, and to think also about having these plays, if reception among friends seemed favourable, being represented on an Italian stage. Because from now on, and including his envisioned play on the artists, he was writing in Italian. Leaving the writing of satirical pieces in German, as well as the struggles between Protestants and Catholics, behind. At least for the moment.

At least for quite some time.

Morelli, as rendered – statesman-like – by Franz von Lenbach

(compare our biographical Sketch), and amidst some of the ›characters‹

of his collection, which was also the collection of someone with a tremendous

literary education (and literary imagination) (source: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

The Spanish world, above all, had taken possession of his imagination. Not only that he eagerly had read and still was reading Calderón, but he did also read one of his comedies aloud to chosen friends in 1845, pretending that what he did read, was actually a Spanish play, and just a translation from the Spanish. In Italian, at any rate, the play was called Il nemico delle donne, its author was Morelli, and it seems that it was favourably received.(55)

Of the plays Morelli did write during the 1840s we do, unfortunately, hardly know anything at all, although we do know that he was also, on a more feuilletonistic or even scientific level, concerned with Cervantes and Ariosto, also two of his preferred writers.(56)

And in 1846 his friend Engelhardt was invited – or allowed – to read his play called Premura soverchia nuoce o il vero prova d’amore. And it was Engelhardt, who seems to have appreciated this play, who apparently said that it was superior to comedies of German Pre-March writers like for example Gutzkow or Laube.(57)

In 1847, finally, he envisioned to adapt the sinister Story of Ill-Advised Curiosity from the Don Quixote, to turn this novella about friendship, faith and the question whether one should seek to know better people one already does trust into a drama (here probably a tragedy and not a comedy, or a tragicomedy; the subject matter Cervantes had found in Ariosto, which also explains Morelli’s earlier interest in both writers in hindsight).(58)

And at least this was what Genelli, his friend at Munich, got to hear, and one can be sure that this was on Morelli’s mind, even if he never did actually carry out his plan.

Also to Pinturicchio Morelli was later referring to

as a ›dramatist‹, being, in that respect, superior to Perugino,

due to his not just putting characters next to each other,

but linking them due to a thought (Morelli 1893, p. 192);

given here a detail from Christ among the Doctors

It does not seem that Morelli, during the 1840s, already had associated his own writing also with his political views and ideas, although he did admire playwright Giovanni Battista Niccolini, and particularly this writer’s historical and subliminally most political play, more a reading drama than a play to be represented on stage, Arnaldo da Brescia.(59)

But the political motif, the political component did add, if only after the major rupture that the First Italian War of Indepencence meant to Giovanni Morelli, and seen in a more broad view, also the panorama of the European Revolutions of 1848/49. Since his experiencing these two crucial years was not at all limited to experiencing these years mainly or exclusively as an Italian patriot.

He had been close, at the beginning of 1846, to have one or more of his plays represented on stage. And obviously he had imagined that the theatre company of Gustavo Modena might be the company that was to adapt his work.(60)

But if it did not come to that either – at least one has to raise the question if the political views of Modena, who was certainly a republican, and the views of Morelli, a declared conservative or right-wing liberal, had shown to be compatible.(61)

Genelli, still being informed as to Morelli’s progressing in his writing, did observe that his friend, somehow, seemed not to be that convinced that he actually had found, and by this: defined his actual profession. And warned him that life was actually too short to remain undecided what to do with it.(62)

And in fact this reluctance and scepticism might have contributed that the one opportunity had passed. But this scepticism, Morelli’s innate scepticism, was to stay with him before and after the two years of the European revolutions. He had taken, partly enthusiastically and partly sceptically, his first steps to become a playwright before 1848. And he was also going to take further steps after it, still envisioning to write for an Italian audience. And still envisioning, although he was coming closer to the age of forty, that this might be what we was to accomplish in life, respectively to do with it.

*

DRAMA AFTER 1848/49

Martin Disteli, Zelotenpredigt (1834)

It is little surprising that it seems to have been, among other things, rage that Giovanni Morelli had to deal with, after 1849. Thus, again, it was rage that stimulated him to write. And while we do know what had enraged him – namely Italian republicans and Italian ultraconservatives (clerics, and probably the Jesuits very in particular)(63) – we do not know what particular incidents had particularly stimulated his rage. But we can guess: It might have had to do with what Gino Capponi had to experience. In 1848. Because Giovanni Morelli got particularly enraged if people he loved were suffering.

At the shore of Lake Como Morelli, in 1851, did not only mentor his friend Niccolò Antinori, who was translating Goethe’s drama Egmont into Italian, but was also concocting new plays, comedies, and now also political comedies.

On one play, the Pino di Lenno, Morelli must have worked over a longer period of time; other plays find a more general mentioning. But Morelli did link the writing of plays with the rage he had to deal with.(64) And we assume, only assume, that it had to do, also to do with Capponi having led, for several weeks a Tuscan government in 1848, but having stepped aside, pestered by political opponents.(65)

And what political radicalism, republicanism might have done to Capponi might also have been contributed to foster, because Morelli was identifying with his fatherly friend and mentor Capponi, Morelli’s general rage, after revolution and war had not resulted with, at least for the moment, turning things to the better, for Italy or for, still and again Austrian-ruled Lombardy.

And in addition to that Morelli, as well as many others, had been bitterly disappointed by Pope Pius IX who had been bearing the hopes of the Italian patriots, but now had turned into a conservative, if not to say, reactionary.(66)

Morelli must have thought out and written numerous new plays and also have revised old ones, and it is, at the moment, not possible to clearly make a distinction between new and old, meaning here: ›re-worked‹. Several titles find also mentioning in the sources (for a complete overview see our Bibliography Raisonné), since Morelli, although his interest, step by step, turned, throughout the 1850s, towards art historical and to connoisseurial studies.

In 1856 he seems to have been, again and for the second time, at the point that he wished his works to be represented on stage. But obviously he was also in need of support to make that happen. And the opportunity seemed to have come after Morelli had recommended literary scholar Francesco de Sanctis for a professorship at Zurich that he, Morelli, himself kindly had declined to accept, still thinking of himself as being rather a man of letters than a teacher of literature, and still thinking of himself, or wishing himself to be a playwright.(67)

Francesco de Sanctis must have been a little puzzled about having to judge several plays that, as he sensed, were written by his friend Morelli. But he decided to confront him with his judgment (that he found the plays rather mediocre).(68)

A judgment that still seems to have caused enthusiasm in Morelli (who admired and respected de Sanctis whose lectures on Dante he had heard). And Morelli, again wrote to his friend, to ask if de Sanctis could not be of help to have these plays represented on stage, namely at Turin.(69)

To Turin Morelli was heading himself (we do not know if de Sanctis further tried to be of help), and also with a portfolio of his own plays, but also to observe what was happening in the capital of Piedmont, and to get to know the political and cultural scene.(70)

He seems to have remained reluctant to take further steps to have his plays represented. And also the second opportunity, if there was such, after already the first had passed in the 1840s, now also did pass.

And the sources do inform us that, in 1858, Morelli had found a new focus of his studies: art history.(71)

In 1874, when asked about his relation to Genelli, Morelli, had, for once, had to comment about his attempts to write plays. And this is the one opportunity that allows us to actually catch Morelli, for once, with a lie. Since he had not burned, as he pretended on that occasion, his dramatical works.(72) Several of them, namely at least three, have been sighted, but, for the moment, remain in private hand, unprinted, and for the moment: also unread.(73)

**

THREE) ENTER LERMOLIEFF

THE ANTECEDENTS OF LERMOLIEFF

Enter Lermolieff in 1874 (source: Morelli 1874-1876/archive.org)

The search for the antecendents of Ivan Lermolieff demands even more patience and detective skills than the search for Morelli’s real antecedents. Since, in this case, he left us with absolutely no clues at all; while as to his real antecedents, at least, Morelli did invent himself an old Venetian provenance, corresponding with his wishes (his identifying with old Italian stock, with Italy and with the Italians), but also corresponding with his general inclination to comedy.(74)

What do we mean by saying ›antecedents‹, since Ivan Lermolieff was a persona that Giovanni Morelli, art historian, invented, to have it speak for himself?

But Lermolieff had antecendents. In terms of other persona that Morelli had, even earlier, to speak for himself. And Lermolieff was also born from the head of Morelli for various reasons, that had Morelli invent a persona to speak for himself.

Finally, various circumstances influenced how he did invent a persona to have it speak for himself. And Lermolieff was also influenced by persona other authors had invented (to have these persona speak for them). And all of this – let us say: origins of Ivan Lermolieff – we would like to put into perspective in the following. In hindsight, naturally, since Ivan Lermolieff, if not necessarily being a really original, a really great invention as a literary persona, was at least Morelli’s most successful invention (if we would leave away here those inventions that were never, or at least for very long, not being recognized as being inventions, his almost perfect crimes, if we may say so, as inventions).(75)

Ivan Lermolieff, in sum, was the hero of the picaresque novel that developed to be also the fortuna critica of the art historical writings of Giovanni Morelli, a hero, crossing the boundaries of disciplines, a hero who, being born from the head of Morelli, entered the thoughts and minds of many other thinkers, readers, and particularly art historians with a similar sense of comedy as Giovanni Morelli, and, one may add, with a similar grim perspective on the (not only art historical) academia.

A direct antecedent of Lermolieff was a quaint playwright named Dall’Ermo that Morelli had invented in 1856 as an alias (drawing on another anagram of his name), to ask, as above mentioned, literary critic Francesco de Sanctis for his opinion on various plays (that Morelli had attributed to Dall’Ermo, but had actually written himself).(76) De Sanctis, sensing the truth at first, seems to have accepted the existence of Dall’Ermo in the following, accepting, at least seemingly, that not Morelli but Dall’Ermo had written these pieces that he, the critic, had found mediocre (it might also have been a way to bury the matter and to forget about it).(77)

This line of literary persona that Morelli needed to express himself, we might now trace further back (to the various literary persona found in Morelli’s early satirical pieces, written in his studenhood; but we could also trace this line into the future, because Morelli was to invent, later, a Mr. Johnson, namely a Yankee from Chicago, to comment on the European art world (and particularly, as it seems, on Jewish speculants).(78) This satire, probably revealing Morelli’s anti-Jewish resentments rather drastically, was never published (and also seems not to be extant), since Morelli himself, also advised accordingly by Layard, held it back, expressing also the opinion that the piece was ›much too caustic‹ (some fragments, according to Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes, were still inserted into Morelli 1890).(79)

Genelli had also known Koch (second from the left) in Rome

If we would think now the history of connoisseurship, being visualized as a family tree, we would probably find lineages that, at least, indirectly, contributed to the appearance of Lermolieff, that Morelli imagined as a Tatar from Kasan (making a distinction between Slav and Tatar).(80) And it might be that Morelli’s rivalry with Karl Eduard von Liphart, a Baltic-German resident of Florence who advised a Russian grandduchess and sister of the present tzar on art affairs, indirectly contributed to the appearance of Lermolieff, since Morelli might have liked to confront Liphart, the ›[old] magician‹ from Russia, or the ›Erznarr‹ (›perfect fool‹), as he was also called by the Morellians,(81) with a young Russian connoisseur of art that, all of a sudden, appeared on the scene, to particularly pester Liphart’s friend, Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle (compare survey below).

But as the primal antecendant, as it seems, as the actual antecendant of Lermolieff we should name, also if this would not have been to Morelli’s liking, a literary persona that Austrian painter Joseph Anton Koch, once, had invented, to have this persona appear in his satirical Moderne Kunstchronik of 1834, a book that had been meant to comment, very critically, if not to say, with caustic verve, on European art affairs.(82)

Thus the primal antecedent might have been an English painter named Christoph from Manchester, who, to send letters displaying his views on art and connoisseurship, had fled the European art world, arriving, more or less, from where Lermolieff was, much later, to embark on his critical mission: from the »Tartarei«. In short: Christoph from Manchester, formerly also a resident of Rome, had fled to Russia, fled from the European art world, and his journey had led him to places as far as Mongolia, Sibiria, and also Tatar regions (various places that summarily and rather vaguely could be referred to as the »Tartarei«), only to be reminded, to often comical effect, of various phenomena, having their origins also in the European art world.

If Lermolieff, hence, did represent critical reason, in Europe, and after having come to Europe, critical reason, coming from Europe, but having sought exile in the East, troubled by phenomena like for example overly wise European connoisseurship (also represented by women),(83) had once fled to Asia, to Russia, to Mongolia. And, above all, the Moderne Kunstchronik: Briefe zweier Freunde in Rom und in der Tartarei über das moderne Kunstleben und Treiben; oder die Rumfordische Suppe had been a book that Genelli had recommended to Morelli in 1839.(84) That is to Morelli who had been busy then to write his early play Kunstkenner, and as early as that, Morelli might also have found, given that he actually did consult the book Genelli rather warmly recommended him, his initial inspiration for his much later invetion of Lermolieff: a persona, also, if one does like so, representing (overly) wise connoisseurship – but here: real connoisseurship – because Lermolieff was also a persona that Morelli, declaredly, meant to humiliate arrogant German professors,(85) in that this Russian Tatar knew everything better than those professors, to whom, thus, were shown their limits by a ›half-barbarian‹ coming from the ›steppe‹ (Morelli’s touchy pride and his anti-Berlin complex, his resentments, in short, are to be regarded as an very important, indeed essential ingredient of Lermolieff and Lermolieffianism).

Even if this lineage, that we do assume here, regarding it to be as most probable, cannot be proven, since, also here, Morelli remained silent as to the origins of his ideas (and he did not refer to Koch himself, at least not in the extant letters to Genelli), it seems obvious that Morelli just inverted the basic idea of Koch, having real connoisseurship return, to pester those who, in Morelli’s view, did represent foolish connoisseurship, that now, more than in 1839, did apparently pester him, because he had now turned to be a connoisseur himself. And his, occasionally hotheaded rivalry with other connoisseurs, Liphart, Cavalcaselle and so forth was obvious.

Liphart who particularly disliked, in the following, Morelli’s tendency to attack while using a pseudonym – and not with ›open ventail‹, as Liphart had it –(86) was one unnamed and therefore less obvious target of Lermolieffianism (Liphart, in Morelli’s view, had also, assumingly, corrupted Bode);(87) and indeed the mask Lermolieff can also be interpreted as a tool particularly meant to attack rivals that to attack Morelli needed a mask.

For various reasons, one of which might also have been his tendency to consider overly wise connoisseurship as pretentious himself, if not being associated with and relativized by some waggish element. But on the other hand Morelli seems to have needed the liberating effect of being able to speak through a mask, his own sensitivities being not less vulnerable than the sensitivities of others. And if everything was just a play, a comedy, it was comedy with various very serious undercurrents, and one could, as situations demanded, switch between the more serious and the more playfully waggish element, in sum: play with that ambiguity of seriousness and waggishness.

The Old Italian that was to appear, at the very end of Morelli’s career on the stage of connoisseurship, the Old Italian mentoring young Lermolieff,(88) only to leave the stage thereafter, was Morelli’s last appearance as a literary persona. A persona that – more or less – had dropped the mask, and once, but rather briefly showed, at a time when indeed Morelli’s life, and also rather short-lived Lermolieffianism was coming to an end.

That had brough positivism into art scholarship, but combined with what one may call a carnival of masks, with serious positivistic ambition also (being represented by the mask of Lermolieff), often and perhaps also all too often, due to the masks, confusing people. Confusing readers.

But on the other hand, if everything was seen in terms of a carnival of mask, this was only reminding the fact that all serious appearances were only appearances, hiding, obviously or less obviously, less visible motifs, interests, subliminal resentments, undeclared rivalries and so forth. And one may even interpret the appearance of Lermolieff as an appearance, declaring for once, paradoxically in hiding, art historical rivalries being a serious game, and reminding that all human affairs have this theatrical quality as such, and that the academia is a place where the play of masks is only – usually – dissimulated.