M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Learning to See in Spanish Milan  |

See also the episodes 1 to 20 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

And:

Learning to See in Spanish Milan

(28.-29.9.2021) A spectre is haunting the world, and it is not communism. It is another collective nightmare:

it is the Leonardo workshop.

– ›Why nightmare?‹, Francesco Melzi is asking, jovially, as we are sitting in the Prado cafeteria, on occasion of the

Prado exhibition on the Leonardo workshop, and on occasion of this 21. episode of our New Salvator Mundi History.

Giampietrino is also with us, distractedly playing with his smartphone.

– ›We were all very individual. Like a family. A workshop is like a big family.‹

– ›We always sent him, for interviews‹, Giampietrino says, without looking at me.

– ›Because Francesco had a better edu-ca-tion. Knew how to express himself.‹

I already had sensed a certain tension between the two of them.

– ›Do you know that Francesco was the first of the Leonardisti, the Leonardo scholars?‹, Giampietrino is asking, without

looking at me, and it is sounding as if he was referring to an awful tribe. As Melzi is making a sort of I-am-guilty-

but-have-mercy-with-me-gesture, I am not sure if he suggests to have mercy with Giampietrino.

I am nodding. Having myself introduced as a journalist from Switzerland, hiding my identity as a researcher, I am a

little nervous, since the two, as they are ghosts, could be all-knowing.

– ›And actually Angela did all the paper work. Dispiace.‹ Giampietrino is putting his smartphone on the table.

– ›We still have several appointments with art dealers, afterwards. Also in Switzerland. Are the Swiss still thinking of

Marignano?‹

– ›Some do. And you mean: Angela… Landriani?‹

– ›My beloved wife was indeed of big help with the manuscripts of The Master‹, Melzi explains. ›And as to politics: we

indeed saw many rulers of Lombardy come and go. It was like a sort of multiculturalism from above, as you would call it.

We had to learn French dances, Spanish dances.‹

– ›I never had thought of it that way.‹

– ›And yes, we have appointments with dealers. But we are always hiding our real opinions, because we tend to like

watching the confusion (also The Master did like to). It’s all like a game. Who painted what. This is a game we liked to

play a lot, back then, in the Master’s workshop. But it is only fun, if everyone knows exactly who had painted what. You

still have to learn to play that game! It’s all about pretending, based on everybody knowing. Like a carnival, like

wearing masks. But these masks have to be half-transparent.‹

– ›I never played that game‹, Giampietrino can be heard mumbling, and I am deciding to change subject.

(pictures in title: Gaudenzio Ferrari, detail; small: Orpheus playing a vihuela. Frontispiece from the Libro de

música de vihuela de mano intitulado El maestro by Luis de Milán, 1536;

below: Sailko (ducato di Milano); Luini: Francesco II Sforza)

One) Milan in 1535

Thinking about writing a double biography of Melzi and Giampietrino, a book about lives ›in parallel‹, I am still

undecided whether to confront them with the idea. For both Leonardo, the master, must have been a centre of their

existence, also after he, the master, had passed away. I am decided, however, to make this interview an exercise as to

the method of biography. How would one confront the task? What methodological obstacles would there be to overcome?

We have little to work with, as to biographical facts. We do know nothing, for example, as to the intellectual education

of Giampietrino. One the other hand we have many works, attributed to Giampietrino. But very few attributed to Melzi, who

also seems to have turned away from running a workshop of his own (while the one runned by Giampietrino seems to have

blossomed).

But what I have in mind is to establish a general frame, a structure that allows us to frame, within a general panorama

of cultural history, the little we have as to biographical facts. This would be a more essayistic, experimental style of

biography. But would have the advantage of staying aware, all of the time, that biography is about the construction of a

narrative. And much can go wrong with that. If we are working with a more transparent way of constructing a narrative,

less can go wrong. Or at least only in a transparent way. Which is also a way of avoiding damage. One should, as a

biographer, respect the subjects of biography. The encounter I am imagining is the encounter every biographer should

imagine. Because in the end, a narrative should stand. And it certainly does not stand, if it immediately could be

deconstructed (so the imagined encounter is actually about doubt, about our own doubts that we should have as

biographers: does something stand, does it pass the hardest test or not? And this we would perhaps see.)

I would start with a crucial date: Milan in 1535, when Francesco II Sforza had died, and, in hindsight, we see the

dawning of a new era. Modern historians have a new period start in the history of Milan. It is about Spanish Milan now,

but I suspect that for people like Melzi and Giampietrino this might have been different. A ruler had died, yes, but the

future was not that clear to see. Lombardy was still embattled, and the Italian Wars not over yet. On the level of

culture however, Spanish influences might have been important much earlier. And one might focus on the history of one

musical instrument for example: the vihuela, on danses like the Pavane, and in general on the history of music.

As on the history of material culture. Did, for example, the money change, after Francesco II Sforza had died?

For Sforza Milan, for the second half of the 15th century, we have the impressive multi-volume work by Francesco

Malaguzzi Valeri, a treasure to work with, also as to the visual culture of daily life. And one might work with that,

asking what exactly did change with the Spanish influence becoming stronger. And on the level of daily life we have one

particular essay by Peter Burke, which I do recall from my days of being a student of history.

Burke did ask, at the beginning of the 1990s, how gestures of daily life did change, the way people walked and talked

(by gestures). And contemporaries seem to have observed very drastic differences, cultural varieties of the peoples of

Europa, as to how the expressed themselves. Political changes, in the end, had a deep effect on everything, but the

crucial dates are only of symbolical importance. What people probably had to do was to adapt, to learn anew how changing

ruling classes did walk and talk, and pramatists like Giampietrino must have started to muse about what new demands could

be met with new artistic supply. Both Melzi and Giampietrino had, at around 1535, learn anew how to see – in Spanish

Milan.

Two) Because Melzi Was a Nobleman

It is about class. Period. And it is about gender, too. For the historian. By which I mean: one should use these big

words perhaps a bit less, but staying aware that social differences do matter, as well as that social roles, and also

gender roles do matter. Always. Melzi and Giampietrino could even be used as classic examples. Because Melzi was a

nobleman. And one of the first questions on my mind would be: did he feel at ease in artistic circles, and did artistic

circles feel at ease with him, the nobleman? Since, as Rossana Sacchi has observed, one can sense that for example

Lomazzo had a certain reserve if speaking of Melzi, the nobleman. The social distance seems to have inscribed into

language, into the little Lomazzo says of Melzi. Hence it goes without saying that class did matter as to the

relationship of Melzi and Giampietrino – the question would only be: how did it matter? Could they be friends?

A question that has been answered by movies like Novecento in a most dramatic (and certainly overly simplified way),

but sometimes question have to be raised in simple terms, so that they could be answered, as soon as everyone would be

paying attention, in a more nuanced way. But I don’t know if they were friends. If they had a common bond with recalling

their master. If, finally, they had a common bond in painting – even after 1535.

Both Giampietrino and Melzi were married, and married fathers. How did that matter as to their relationship? Angela

Landriani, Mrs. Francesco Melzi, recalled as a known beauty, was a noblewoman of the kind Luini has drawn and painted

(see above; picture on the right: nga.gov). One does link the drawing as the painting with Ippolita Bentivoglio, but I

think, it would be more likely that we see some of her daughters; and perhaps we see someone else anyway. At any rate:

Class established a basic structure who was painting and who was painted. And Melzi, on some level, had ignored, the

conventions of class, by joining, as a nobleman, the artists.

Joining his class again at home, after returning home from France in c. 1520, he seems to have adapted more with class

conventions, in that he did not embark on running a commercial enterprise such as an artist’s workshop. The question

would be: how and when did he transform his creative energies, his skills and knowledge into doing something else than

running a commercial workshop? And one other question will be raised at its time: did he never paint Angela Landriani,

his beloved wife, or have we, posterity, only failed in identifying Angela Landriani in paintings, and failed in identifying

paintings by Melzi?

Three) Because Giampietrino Was a Businessman

Most dates that we have as to Giampietrino seem to indicate that for him culture was associated with business. Already

capable to buy a house in 1509, we see him having an apprentice early, and teaming up with Giovanni Francesco Boccadoli

in 1517. If we look at the dates we have around the year of 1535, we seem him working in Milan cathedral (1533), and

teaming up with Alessandro Bizzozeri in 1543. And it was about selling goods (what kind of goods?) in Italy and Spain.

Giampietrino had discovered a Spanish market. His son, Girolamo, was appointed as an apprentice. Giampietrino had also a

daughter, Angelica, and we hear of her dowry in 1547.

The impression that Giampietrino was indeed a flexible businessman is confirmed by looking at some of his pictures:

flexibility shows in that he turned the figure of Christ into a Mother of Christ if it was ›needed‹ (or vice versa). As

to the Giampietrino Salvator Mundi group one can observe that the whole group is built on a scheme with the blessing

hand as the fixed point. The rest of the picture was, as one might say, arranged around that central gesture (open hand

gesture of blessing), just as a musical mass is performed on basis of fixed elements to which some parts are added,

according to daily needs.

One does wonder how Francesco Melzi might have looked upon the vast production of his colleague, if he did take notice at

all. A production that included the mythologized nude (Diana). Dates that somehow would link several of the

Leonardeschi at around 1535 (Luini had already died in the 1520s) are lacking alltogether. Both Melzi and Giampietrino

had married, as said. But did they attend each other’s marriage? And did Giampietrino take notice that Melzi was to

become a sort of curator of Leonardo’s notebooks (showing them, and probably also: lending them to people). One does

wonder who exactly the three hands are that seemingly can be distinguished in the Codex Urbinas (we don’t know,

if Angela Melzi was involved), but it is also noteworthy that sceneries of these two biographies are totally different: a

Spanish market here, Leonardo-philology there. A life in the urban countryside here, combined with representative

activities (Melzi was consulted as to the question how the ›entrance‹ of dignitaries (the wife of Francesco II Sforza;

the Emperor) had to be organized). And while we have to draw our conclusions as to the cultural interests of

Giampietrino from his pictures, we know that, once, Francesco Melzi consulted a codex containing diverse Spanish or

Spain-related literature in a library. The Spanish cultural element is there, as to the two of them. But it has to do

with business on Giampietrino’s side, while it – seemingly – has to do with leisure on the side of Melzi.

– ›The King of France was a pavone‹, Melzi says, noddingly, ›but his mother, Louise of Savoy, was great.

She was the actual ruler. Very determined woman.‹

– Do you know that he was famous for his nose?‹, Giampietrino asks.

– Yes, the letters of the Valois do speak of the family nose.‹

– ›And he was famous for having been caught by the Emperor. Had to serve some time in Madrid.‹

Four) The Knight of St. John

One does wonder what opinion Francesco Melzi might have had of Francis I who made him a valet de chambre in 1520.

It is possible that Melzi might have stayed in France. But he returned home, he married, he raised children and one of

his children was to become a knight of the order of St. John – fighting the Ottoman Turks, and seems to have been caught –

by Muslim pirates.

One has to recall that in 1453, a year after Leonardo da Vinci had been born, Constantinople had been conquered by the

Turks. The Christian west, among other things, reacted with renewed interest for crusades – to free the city. A

crusade also Pope Leo X expected Francis I to lead. Instead, in the 1540s, flexible Francis I allied with the Turks against

the Emperor, and one does wonder how Francesco Melzi might have reacted to that: Italy being attacked by the French king

being an ally of the Turks. And one son of Melzi fighting the Turks as a knight of the order of St. John (Baptist).

If Melzi might have had sympathies for the French King earlier – how did he feel after 1525 (the King being caught by the

Emperor), and afterwards? We don’t know that, but we can be sure that Melzi had personal memories of the French king,

and that he spoke, to other people, of the festivities Leonardo had arranged in France. Melzi, who had spent his

childhood in Sforza-ruled Lombardy, had grown up under the rule of the French, had seen the Swiss, and had lived, after

three years in Rome, in France, near the court. Did he feel at home at all, after having returned from his travels? What

exactly was home? And: To what degree it was rather ›class‹ than anything else?

Five) Cerca Trova

– ›Whose idea was the Monna Vanna?‹, I want to know (watching Giampietrino from the angle of my eyes).

There is time for a couple of more questions.

– ›We had people for that‹, Melzi says, seemingly inclined to reveal more, while Giampietrino seems busy again

with his smartphone.

– ›You know how this is, if people work together. One thing leads to the other. It’s difficult to say whose idea it was.

The Master could become very angry at times. But he was also the most tolerant Master of all, the most liberal. And

as I said earlier, the game we used to play, as to who painted what…‹

– ›There was definitely less frivolitas in our days‹, Giampietrino says, waving with his smartphone.

– ›Why don’t you ask us about the Salvator Mundi? We have an appointment with some people, because a new version

seems to have come up. Our Francesco will play the distinguished scholar, and I will play the businessman.‹

I have noted that some of the so-called leading Leonardo scholars have entered the cafeteria.

– ›Well, whose idea was the…‹

– ›Which version?‹

– ›Well, the… the…‹

– ›When the Salvator was invented, none of us was yet part of the team. We don’t agree as to when it was invented. It

might have been that it had to do with the ancona. The Virgin of the Rocks, which, as you know, was a rather

complicated matter. Lots of different parts. A God the Father was on top.‹

– ›It is also possible that a pilot version was among the paintings that the Master had to sent to the wedding.‹

– ›Maximilian?‹

– ›Yes. But the people of Ambrogio de Predis were an even more complicated tribe that we were. They are also consulting

nowadays, as you might know.‹

– ›No, I didn’t know that. But who painted the…?‹

— ›There is an 18th century picture in the exhibition, downstairs. Have you seen that?‹

– ›Well, yes, to me the landscape seemed a bit…‹

– ›But why don’t you ask us more about the Salvator Mundi version Cook? Luini is also consulting nowadays, by the

way. Have you met him?

– ›No, I was hoping…‹

– ›Version Cook was the result of a little game we all played.‹

– ›You mean… the attribution? Is Boltraffio also consulting? And the Master…?‹

– ›Yes. Luini people were very busy in the 19th century. We could not allow that everything was attributed to them,

so we thought, the game we played in the old days…‹.

– ›But… are you all-knowing?‹

– ›No. But it is perfectly clear who did paint which part of the Salvator Mundi. But this is not interesting. It is all

about the game. The game.‹

– ›The game?‹ (I see the Leonardisti waving. They seem to have spotted the two ghosts, who now have stood up. We are

practicing social distancing, due to the plague in 1520s Lombardy, but Melzi seems willing to add something to what he

had already said. I am hearing him whispering into my ears.)

– ›Terrible thing, a workshop. A collective nightmare. Nothing for individualists. And since people also tend to see

with their ears…‹

– ›You mean that your part, your contribution, which is, frankly… Frankly: Why did you disappear? Why did you leave

painting at all?‹

They are waving good-bye as they are bound to leave with the Leonardisti.

– ›I did not. It’s all there. It’s there. In the miniatures. Lomazzo has called me a miniaturist. Those who shall seek,

shall also… It’s all looking and thinking. Now good bye.‹

Selected Literature:

Peter Burke, The Language of Gesture in Early Modern Italy, in: Peter Burke, Varieties of Cultural History, Ithaca

1997, p. 60-76

Andrea Gamberini (ed.), A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Milan. The Distinctive Features of an Italian

State, Leiden/Boston 2015

Francesco Melzi:

Rossana Sacchi, Per la biografia (e la geografia) di Francesco Melzi, in: Acme 70 (2017), p. 145-161

Giampietrino:

See the essay by Pietro C. Marani, in: Legacy of Leonardo, p. 275ff.

Further Reading:

Cristina Quattrini, Bernardino Luini. Catalogo generale delle opere, Torino 2019

(picture below: Gaudenzio Ferrari)

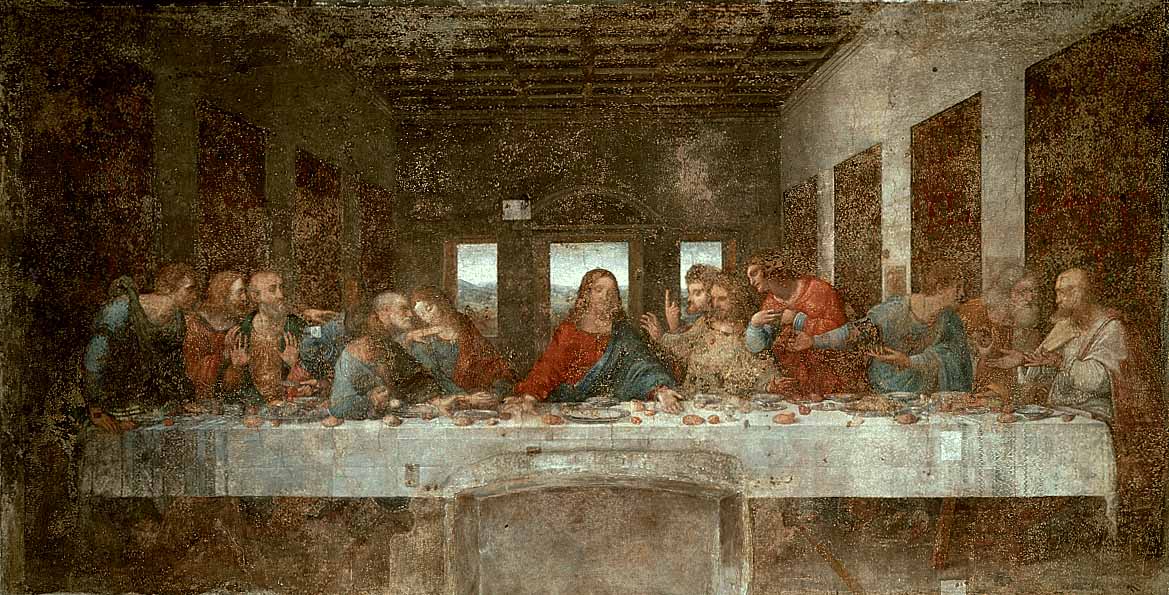

The Bottega of Leonardo da Vinci

The picture of the bottega of Leonardo da Vinci is not as blurred as one might imagine (for details see Seidlitz 1935, p. 530; Marani 1998). We will focus here on the early and middle years (up to 1512), and not on the late years, and one might begin with saying that with Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono we see two figures enter the orbit of Leonardo at the beginning of the 1490s that we believe to know rather well. We also see Salaì enter the orbit, at a very young age, and we have, in addition to that, a couple of names, names of figures that we do not seem to know very well, or not at all (a Giacomo, Giulio Tedesco, Galeazzo). Last but not least we have the Giampietrino problem: Giampietrino enters the scenery, but it is a matter of controversy (as far as this question is debated at all), when, since also Giampietrino is still very young.

It is noteworthy that Marco d’Oggiono, already at the end of the 1480s, seems to have had an own apprentice, and that Marco and Boltraffio did create the Pala Grifi together (a picture today in Berlin; picture above), even before Leonardo began to work at The Last Supper in 1495. Due to the work of Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi we today do know more about Francesco Galli, also called Francesco Napoletano, who did die in Venice as early as 1501. One might imagine that Galli went to Venice with Leonardo in 1501, and if Galli, during the 1490s, for example might have cooperated with Marco, we would have found an interesting perspective: since, if only one single picture of the Marco group would be associated with Francesco Galli/Francesco Napoletano, we would have a picture with hand option 2, a picture that must have been created before Galli died in 1501. Which would mean that hand option 2 must have existed early, and my theory of the pentimento in version Cook as a mere switching from (preexisting) option 1 to (preexisting) option 2 would be positively proven as well as the theory of the pentimento supposedly showing the creative energy of genius (changing his mind) would be definitively falsified.

Brief: in the 1490s Leonardo mentions once that he had paid ›two masters‹ (probably Marco and Boltraffio) for two years; and once that he had six bocche to feed (probably again Marco, Boltraffio, plus Salaì and some of the unknowns).

Below a rather early Marco picture (according to Janice Shell), the Young Christ Blessing of the Galleria Borghese:

And here is a picture (not the only known picture) by Protasio Crivelli, formerly the apprentice of Marco d’Oggiono (picture by Sailko; the date appears to be 1498; location: Naples, Museo di Capodimonte):

In 1501 (3.4.) Pietro da Novellara informs Isabella d’Este that Leonardo seems to live ›from day to day‹ (see Marani 1998, p. 14). And he has seen Leonardo intervening from time to time in portraits done by two of his garzoni (»fano retrati«). But who are these, and which portraits are these (if this would have been about a Isabella d’Este portrait, Pietro would have noted; and after the Sforza had been expelled, portraits of court ladies and courtiers made no sense)? After having written on the picture of a young woman in the Columbia Museum of Art in one of the last episodes, I would now suggest the following:

Leonardo might have done a portrait of a Sforza court lady in the early Milanese years (and still in the Florentine portrait style), a portrait in terms of a drawing or a cartoon. He might have begun also a painting, but since the Sforza court got expelled and exiled after the French invasion, he might not have finished such portrait. He might instead have used it for the instruction of his garzoni: the Columbia picture might have been the one begun by Leonardo (as he seems to have begun portraits with the face, as later in the Mona Lisa), a picture that he might have had a pupil finish, with him retouching it again, adding some lustre. The picture in a private Russian collection might be a second version that he had a pupil repeat (after the first version and the drawing, respectively the cartoon). The Columbia picture shows much gusto for the grotesque, the second version less so, but still to some degree. Thus we would see pictures that have their origins in the first Milanese period (and even in the early Florentine period), but were actually done later (after 1500). And Leonardo might have had a hand in the Columbia picture whose head with the hair as well as the ornated hair net superbly being modelled into the dark is of exquisite quality (as also a single one pearl is, while other pearls are rather mediocre as also the bust and the modelling of the dress is). We see, as I have attempted to show in episode 13, two pictures that fit into the context of Leonardo’s thinking and doing rather than into the context of Boltraffio’s autonomous work:

In 1504 a Jacopo Tedesco, in 1505 a Lorenzo (di Marcho) enter the orbit of Leonardo.

In around 1505 Fernando Yáñez enters the orbit of Leonardo, helping him with the Battle of Anghiari (as also does Riccio della Porta). Yáñez cannot be the author of the Prado Mona Lisa, if the Louvre Mona Lisa was finished only years later, since the dates (showing that Yáñez was active in Spain after 1506) do not allow to postulate it. In works of Yáñez done in Spain, however, we find echoes of Leonardo’s works (see the example below).

Around 1507 Francesco Melzi becomes a pupil of Leonardo (and also a sort of secretary).

In 1511 (or even earlier) Giampietrino is an autonomous master.

In 1511 Salaì seems to have created a (signed and dated) picture of Christ:

In around 1511 we see Marco, Boltraffio, Giampietrino and – Giovanni Agostino da Lodi in close contact, not only because we have a source indicating exactly that – we also have pictures indicating exactly that, and one of these pictures seems to be even dated (but the ›date‹ – ›XII‹ – is rather referring to the ›age of Christ‹):

The Prado Mona Lisa (below) was probably begun at the time Leonardo also started reworking or completing the Louvre Mona Lisa, probably due to Giuliano de’ Medici wishing so, and hence perhaps in around 1511/12.

In around 1517 Marco d’Oggiono is cooperating with Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (see Shell, p. 173).

***

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

»…in the evening at twenty-two o’clock we saw the Holy Sindon or Shroud«, Antonio de Beatis is writing in his travel account, his trip across Germany, France, the Netherlands and Northern Italy having enabled him to recall, as an eye witness, essential sights of the visual culture of Europe in 1517/18. These sights included, as said above, the Ghent Altarpiece, the Turin Shroud and also Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan (picture of the Turin Shroud: Dianelos Georgoudis). Only the now so-called Turin Shroud, however, did apparently stimulate him to include a visual reproduction, a drawing, into the manuscript copies of his account.![]()

See also the episodes 1 to 20 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

A Brief History of Digital Restoring

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS