M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Looking Back At Conques |

See also the episodes 1 to 5 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

And:

Looking Back At Conques

(7.-8.7.2021) Weasel or ermine? A weasel can stand in for an ermine, if it makes sense that the animal, in a certain context

is obviously supposed to suggest the idea of purity. Why? Because such an idea that an ermine is to be associated with

purity, produces a kind of magnetic field: it does absorb the ermine-like representation, producing still the supposed

meaning that, on a certain level, the picture is about the idea of purity, about a young woman, to be associated (rightly

or not), with purity and innocence. This literally makes sense, even if the modern expert may find, the ermine-like

representation can be ›read‹ as the representation of a weasel. But the modern-eye-expert-view does produce an

anachronism. The Renaissance eye would not have cared about the difference, perhaps not even have known it, and not have

›read‹ the weasel as a weasel. Because this, simply, would not have made much sense.

Here comes the sixth episode of our New Salvator Mundi History. This time it is about rock crystal versus glass.

A ›weasel or ermine problem‹? We will see that, yes, it is the same type of problem. But we will also care about the

differences, even if we are going to explain that it did not really matter, as far as the producing of sense or meaning

was concerned.

We are going to look back deep into history. Looking back to the Middle Ages, and even to Antiquity. Showing that,

imperial signs, Christianized imperial signs, Renaissance imperial signs of power, have a history. A material one, and a

history of producing meaning, apart from, obviously, also a sensuous one (picture of Sainte-Foy at Conques: ZiYouXunLu).

One) Antiquity

Imagine to be an archaeologist. Knowing the insignia of Roman emperors – sceptres, double-orb-sceptres, standards –

perhaps from coins, perhaps from other pictorial representations. When suddenly, on Palatine Hill of Rome, real insignia

of a Roman emperor, probably of Maxentius, the antagonist of Constantine, are unearthed. If you are the archaeologist to

unearth them, you are probably experiencing the story of your lifetime, something that is to mark your life, as far your

professional career is concerned. But any archaeologist, any scholar might sense what this is also about: a something,

the insignia of Roman emperors, that, within our imagination, are being represented by pictorial representations, by

knowledge also, can suddenly be represented by real objects. And one will understand that there must be, despite all the

enthusiasm, also a certain reluctance at play. Can this be real? Which means: can the objects be real indeed, can they

really be what we are thinking them to be? Can they be included within our imagination, within our knowledge? And:

can this experience be real? Or might it be just illusion, fallacy, or just a dream (picture above:

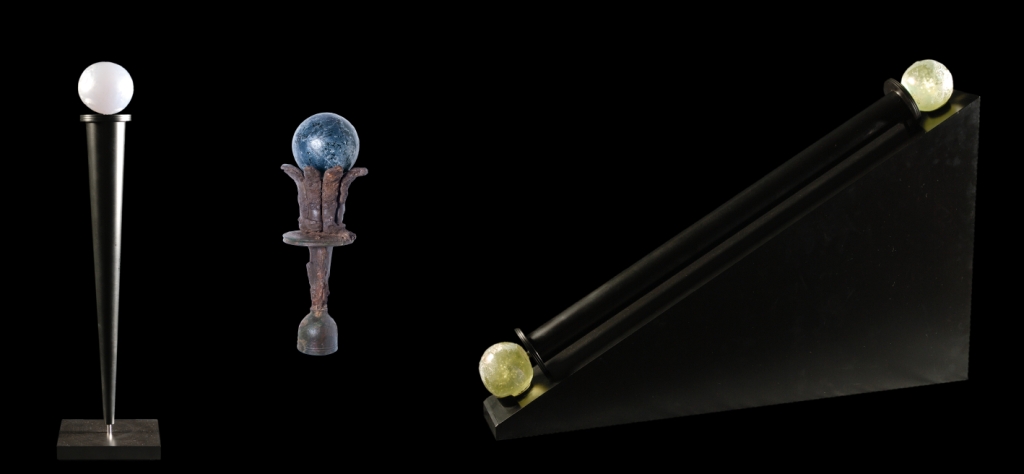

archeopalatino.uniroma1.it; plus detail from Palazzo Massimo alle Terme exhibition brochure)?

The Italian archaeologist Clementina Panella, along with her team, faced this experience, when, in 2006, the team directed by Panella,

unearthed a chest at Palatine Hill, a chest containing insignia, a chest thus: containing also orbs, including two made

of glass that also had been gilded (and on these two, we are focussing here: above these two orbs made of glass are being

represented by three views (3a,b,c); for more informations see here).

A scholarly publication followed in 2011, the year a now notorious Salvator Mundi painting was also presented to the

world. Embodying the very same problem: could this painting, now attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, be included into the

general idea of who Leonardo da Vinci was and of what he did create? The painting included the depiction of a orb, of an

orb replacing the more common globus cruciger, a symbol that can be interpreted as the Christianized version of the

insignium of a Roman empire. While the orb might have been topped by an eagle in Roman times, Christianity had it

replaced by a cross. But Christian rulers, kings and emperors were to adopt the symbols of power, creating new ones.

Christianized ones, but adopting Roman ones. But the supposed Leonardo da Vinci painting did not show a globus cruciger,

but just an orb, seemingly being made of rock crystal or (as others think) of glass.

Two) The Middle Ages

It is strange but also significant that a Medieval statue that is actually ornated by four orbs made of rock crystal,

has never been part of the Salvator Mundi debate (pictures above: youtube.com and youtube.com). I first

encountered this famous statue, the statue of Saint-Faith (now in a treasury nearby the abbey of Saint-Faith at Conques, France),

a statue which is actually a reliquary, when being a student of history during the 1990s. Many a student will

encounter this topic, simply because it is a topic that can sum up so much. The Medieval cult of images (including the

danger of idolatry) can be discussed, but also the problem of authorship in general (since the statue, on a certain

level, has rather a collective author, not a single one that we would know: it is the product of centuries and centuries

of bricolage); and of course the cult of saints, here a saint (actually a girl) that has been given a crown, that is

represented sitting on a throne and, occasionally, was carried around as if being a ruler. Since it was treated as if

being a real person, the statue also, occasionally, held court as if being a ruler. And although the four rock crystal

orbs do not seem to be much in the focus of specialists, also these orbs might be interpreted as quasi-insignia of a

quasi-ruler (and intermediary between the Christian and God): the saint.

But the statue, being ornated by an abundance of gold and precious stones (including a crucifixion scene, carved into

another rock crystal, that ornates the statue on its back side), does not only evoke the idea of imperial insignia, but

also that of the heavenly Jerusalem as being described in the Bible (Revelation, chapter 21), with precious stones and

gold being given much prominence (and with glass only treated as something to compare with as to purity). The splendour

of earthly jewels and gold can be interpreted displaying exactly this light, this radiance of the heavenly Jerusalem and

of a heaven in which the saints (Saint-Faith, but also Charlemagne) are thought to be residing next to Christ.

One might say that we have two ›magnetic fields‹ to work with, two central ideas that we should be aware of, if

discussing orbs, precious stones, divine aura and light, as earthly it might be: the idea of imperial signs, the signs of

power, and, secondly: the idea of a heavenly, a New Jerusalem that might or will come down to earth, where it might

already have been represented by Christian artists and Christians, in awaiting of its coming (for examples in form of

cathedrals, but also in form of church interiors in general and in many other forms, for example in form of the chateau of

Chambord, which, as to its cubic central building, the donjon, evokes the description of the New Jerusalem in Revelation,

chapter 21).

All this should be seen as the Medieval background of what we are encountering, if discussing Late Medieval and

Renaissance pictures that include an orb and precious stones, and also are meant to display a divine aura. Pictorial

means of representation, in some way, do replace the experience a pilgrim arriving at Conques and encountering the statue

and its cult might have had. Modern scholars have, namely the Center for Early Medieval Studies, University of Brno,

has sought to re-enact this experience by means of film (and music), and we can take advantage of that: by showing how rock crystal,

how an orb made of rock crystal does appear if being lit by candlelight:

the picture above does show exactly this: the inner fire, a sort of fiery milky way inside the orb, if being lit by a

light as vivid as candlelight. And what we also can see are several inclusions, also being lit, if only for split

seconds, by the candle that can be seen on the right side. A splendid way to become aware what problems the pictorial

representation of a rock crystal orb, a static representation, might face, in that such a representation does replace a

living experience, including a vivid light, that, partially, perhaps might be brought back by staging such a picture

within candlelight.

Three) Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

Now we are prepared to address the ›weasel or ermine‹ problem anew. On the left we see the depiction of Charlemagne from

the Crucifixion of the Parlement of Paris. This was the picture at the beginning of our New Salvator Mundi History.

Due to Charlemagne holding an orb that a specialist has interpreted as a representation of rock crystal, we could link

this picture to the Salvator Mundi version Cook, which shows an orb that another specialist, independently, has

interpreted also as a representation of rock crystal. Both orbs replace the traditionally awaited globus cruciger, and I

think that these two orbs are corresponding, because the Salvator Mundi orb was meant to correspond with the

Charlemagne orb. In other words: I think it was meant to be its equivalent, as far as Christ, as the universal ruler,

hands out the imperial insignium to the emperor. It simply makes perfect sense that there should be pictorial coherence.

And this makes sense, if the Salvator Mundi was painted for the French monarchy, striving, in 1516-1519, for the crown of

the Holy Roman Empire, the crown of Charlemagne, and thus for exactly the insignium that Charlemagne holds in his hand.

I will now give my view of the ›rock crystal or glass‹ problem, showing also that this debate, decidedly, has been too

superficial. Simply because we have to be aware of two questions: of the question of how these representations were

meant to be ›read‹ on the one hand, and only on the other hand: of how these representations may have attained this goal,

to have been ›read‹ in a certain way (and the debate, decidedly, has focussed too much on this second question, while

neglecting the first one, and thus producing an anachronism).

We may begin with saying that a representation should not be equalled with a real thing, and if these orbs were (or one

of them was) meant to be ›read‹ as being rock crystal – their size is, compared to actual rock crystal spheres, simply a

bit exaggerated. This may remind us of the fact that imaginary components may come in, also in visual representations,

which, on a certain level should rather be compared with the description of a rock crystal orb, as we would find it in a

novel.

But more important is, in my view, the improbability that these two orbs were meant to be ›read‹ as glass. And this for

two reasons: what we see here are depictions of imperial insignia combined with pictorial evocation of a divine aura, and

it seems rather to be unimaginable that for such aim, it should have been the intention that a viewer should see glass

here (if the noble materials, defined with Biblical authority, were gold, precious stones of crystalline clarity and

light, but not glass, even if the imperial orb shown above was made of glass – we should recall that, originally, it had

been gilded).

The second reason derives from the fact that, if the Salvator Mundi orb was meant to be ›read‹ as glass, this goal was

attained by representing the impurity of glass, the inclusions of air, as being the identifier of it to be ›read‹ as

glass. And this again, makes no sense, if a viewer was meant to see signs of power and divine aura. Impurity, as an

identifier for glass, makes no sense at all here, and what we see in the Salvator Mundi orb, is actually a sort of

›crater landscape‹: we see rough ›glass‹ that has not been polished to the level that the surface shows smoothly,

but the inclusions near the surface have, by some polishing, been ›unearthed‹. We don’t see actual air bubbles, but

actual oval halfs of inclusions that have been ›opened‹ by polishing, with the light playing in these ›craters‹.

Said this I’d like to recall the ›weasel or ermine‹ problem: glass can stand in for a precious stone, just because it

displays such irregularities that, if we think the orb to be a precious crystalline stone, bring out light, because the

light is allowed to play in these ›craters‹.

In sum: I think that what we are meant to see in both depictions is a precious stone, a gem, a jewel, not necessarily or

specifically rock crystal, but perhaps of the sort of the mysterious stone in Revelation 21,11 that is called jasper, but

cannot be jasper in the modern sense, since it is decribed as being cristalline-bright (like for example a diamond).

Again, to ›be read‹ as rock crystal the orbs are rather too big, but what we are meant to see are gems, and as far as the

Salvator Mundi orb is concerned: it could be that glass, with inclusions, stands in for a gem. I do not know enough

about rock crystal to say if it also could be rock crystal (perhaps standing in for the mysterious jasper), but at least

theoretically, in my view, it could also be that rock crystal, if not being polished to the level of a really smooth

surface, would also show this ›crater landscape due to inclusions‹ (similar, by the way, to the Maxentius glass orb, as

shown in depiction 3a, above).

Selected literature:

Beate Fricke, Ecce Fides. Die Statue von Conques, Götzendienst und Bildkultur im Westen, München/Paderborn 2007.

Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence. A History of the Image before the Era of Art, London 1994

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

Here we look at another Valois court style portrait. This time it is Caterina de’ Medici being represented (c. 1536), who was married to the second son (Henri) of Francis I (the future Henri II). And if you would think that she might have been the one who might have brought a Salvator Mundi painting with her, from Italy to Fontainebleau or other places associated with the French monarchy, it is the green background, here as in the (virtually reconstructed) Salvator Mundi painting that makes this rather unlikely. Or do you think she might have brought a real treasure with her, a painting by the master of masters, Leonardo da Vinci, and she did allow that such untouchable masterpiece was retouched in green by a Valois court artist? Only to have it match with the background colour of (many) official Valois court style portraits?

See also the episodes 1 to 5 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS