M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Miscellanea Morelliana

(Picture: tias.com)

Morelli and the Wild West

One) The One Picture of, the One Painting by Billy the Kid

No, we have no painting by Billy the Kid. – What we have (or at least believe to have) is one authentic picture of Billy the Kid. The one picture that everybody does know, that appears in every history of the Wild West (and also in the Pictorial History of the Wild West of 1954; see picture above; the first picture within that history, by the way, who would have thought of that… is indeed the picture of… a rifle).

Of course we do not have that one photography in a literal sense (it has recently been sold, as everybody does know, for a good price).

But what is interesting is that other people believe (wish) to have pictures of Billy the Kid, or even are convinced indeed to have such pictures.

But how to authenticate such pictures? And here of course visual properties come in. The one authentic photograph does serve as the one reference, and the one pictures gets processed by any kind of forensic programmes etc. (watch for example this interesting programme here, which has all the classic motifs of a classic authentication campaign).

What has this all now to do with Giovanni Morelli?

Well this is to remind not to confuse things that, even in Morellian studies, got and still get, occasionally, confused. It is one thing to ascertain the identity of a person (by comparing a real person’s ear, for example, with the ear shown in a passport’s photograph; or by comparing the ear shape shown by the one authentic Billy the Kid photograph with the ear (or face shape etc.) shown by another photograph); and it is another thing to compare how the ear shape is rendered in the painting by one artist (because this one artist is ›imposing‹ his notion of ear anatomy upon form) with how the ear shape is rendered by another artist. And here the one painting by Billy the Kid comes in.

Because in order to speak about stylistic consistency (now in the context of art) it would not be enough to have just one painting by Billy the Kid. If we assume that the style of one artist shows stylistic regularities (that serve us as clues in authentication processes), we have to show series (unless we have at best single similarity, which is something, but not more than single similarity, which also can be accidental; regularity is only made plausible by the series). And if the consistencies that shine out in such series have something to do with for example the consistency of ear shapes within the real family of Billy the Kid, is another question. But this (only seemingly) absurd question has to be raised because all to many art historians have just assumed that stylistic consistencies in art do show as consistent (or nearly as consistent) as they show ›in the flesh‹ (or at least as consistent as a fingerprint). One has seen and still tends to see the connoisseurial practices of Giovanni Morelli and the forensic practices of Sherlock Holmes in analogy, although the Sherlock Holmes of the classic Holmes stories was never concerned with Morellian properties. The Holmes of the Holmes stories did in fact compare anatomical shapes (shapes ›in the flesh‹ with painted shapes for example in the Hound of the Baskervilles novel; see Cabinet II), but, as said, this is something else than checking for, and comparing of Morellian properties. What these practices have in common is the comparing of form (and also the working with types; the family type on the one hand; the ›basic type‹, which may be equalled with the inner notion that a painter has of form, on the other; and in both cases these types are mere mental constructions and do show only in terms of phenotypes, that is: actually realized forms, realized by hereditary laws of nature, or by artists’ practices).

But that painters actually painted ears as consistent as ear shapes appear within families must not be assumed by principle, but must be shown in every single case. By showing series. And by explaining why (based on what exact comparisons) a work in question should be placed into such series that make the oeuvre of a particular artist. (Moreover: it does bear repetition (compare Cabinet II and Cabinet III) that Giovanni Morelli did not base his attributions on the observing of single shapes alone, that is: he did not recognize painters by the way they painted ears or other detail alone, and did in fact also explicitly recommend twice not to do so, but to consider the close observation of such details as a mere aid and as a control of one’s general impression, apart from the reasonable general concern for provenance information and historical documentation that was more or less taken for granted.)

Two) Appreciating the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show (Rome/Florence 1890)

While it is not certain that Giovanni Morelli actually attended a show of Buffalo Bill who was touring, in 1890, in Italy, it does seem that, at least, he did discuss, with his pupil Jean Paul Richter, how Buffalo Bill did things (see Jean Paul Richter, Diary, 23 March 1890). That is: how certain illusionary effects within that Wild West Show were accomplished (glass balls, appearingly hit by bullets, were, this at least was the rumor, simply exploding, and not due to actually being hit). And this is also part of someone’s visual education, someone’s visual apprenticeship: to think (or not to think, that is: to forget) how illusionism does work (or perhaps also: how myth constructing does work; and perhaps also: how the spreading of rumors does work).

A book on the spreading of mass culture American scholars have called Buffalo Bill in Bologna. And some snippets may be added to the picture given there. For example that, according to the diaries of Jean Paul Richter, who attended the shows of Buffalo Bill repeatedly, Buffalo Bill seems to have challenged the Romans, that is the Roman horse riders (and the Italian riders in general). And this also might be called a meeting of ›Wild West (mythology)‹ and ›Old Europe (mythology)‹ (Giovanni Morelli, by the way, had been, in his youth, a dedicated rider as well, if not studying poetry on horseback; compare our chapter Visual Apprenticeship I).

A Rough Riders’ Congress or American cowboys in the Roman Campagna (picture on left: iitaly.org; see here)

Three) The Stilt-walk Across the Niagara by a certain sig. Gaspa Morelli (in 1859)

It seems to be a phoney story, at least it is a story that has been challenged. That a Yankee boy did cross the Niagara river, in April of 1859, on stilts. Nearby the Niagara Falls. A Yankee boy that, according to that story (that now does also circulate on the web), chose as his artist name the name of Gaspa Morelli.

In the summer of 1859 tightrope walker Charles Blondin did cross the Niagara Falls; and if the Morelli story indeed is a phoney story (and it has actually nothing to do with ›our‹ Morelli anyway), it still does read, in hindsight, as something redolent of Morellian spirit. Due to a cheeky inserting of an episode into history, just as the (historic) Giovanni Morelli did occasionally insert ideas that were born our of his waggish nature, into other people’s heads. Here we have even a story with stilts. And a story with someone, an American boy, picking as his alias, in 1859, the name of Morelli. While ›our‹ Morelli did pick the alias of a Yankee, a Mr. Johnson of Chicago, only in the mid 1880s (compare our chapter Interlude II).

(Picture on top: Wladyslaw)

***

»Bereits Morelli…« or The Ear in Frans Hals

(Source: Grimm 1989, p. 234; quote beginning on p. 233; section on »Zuschreibungsfragen« in the Frans Hals oeuvre catalogue by Claus Grimm; compare also Cabinet II, question/answer No. 11)

***

The Encyclopædia Britannica and Wikipedia on Giovanni Morelli

As someone who just has written a book on Giovanni Morelli I feel not entitled to correct Wikipedia articles on the same subject, or to ›edit‹ the Encyclopædia Britannica. Still I’d like to give my views here, making transparent with what I do not agree, and what seems to me questionable tradition very in particular. Both articles were retrieved on September 11 of 2015.

One) The Encyclopædia Britannica on Morelli

The name of ›Nicolaus Schäffer‹ was not Morelli’s original name, but a mere invented name that Morelli used in his Balvi magnus of 1836. Furthermore: Morelli certainly cannot be given credit for establishing the foundation of art criticism (whatever this is supposed to mean). Which means: the introduction to the article yet contains a factual error and, as to the general interpretation of Morelli, mere nonsense. Art criticism, even in terms of an academic discipline, existed long before Morelli. And academic art history took, in general, little notice of Morelli at all, as far his vision of a future Kunstwissenschaft was concerned.

The article does know nothing at all of Morelli’s actual intellectual biography (his ambition to become a dramatist, which is: his actual literary ambition); it does transmit the information of a ›Lex Morelli‹ (which comes from Layard’s portrait of his friend), a law of which only and exclusively Layard did know at all (and most likely is to be counted among Morelli’s waggish inventions). Of Morelli’s activities as a picture dealer the article does not know either (transmitting only the heroic picture of Morelli saving works of art for the benefit of his home country, and not the picture of Morelli also selling and helping to sell Italian art to foreign collectors).

As to the Morellian method the article, like any other article, does struggle, because the discipline of art history never found it necessary to put the practical side of the method under scrutiny, nor to unfold a systematic critique of Morelli’s writings that certainly do not meet ›scientific rigorousness‹, and be it only for the simple fact that the documentation of reasons for or against attributions is in general fragmentary (and often less than that).

Still the article does accept (as does art historical tradition) that Morelli was (and that later also Berenson was) very successful in correcting attributions (and indirectly in assuming that this was possible on the basis of actual existing formal analogies in paintings, that is, on the basis of stylistic ›formula‹). None of this has ever been tested empirically (and confirmed) or put under scrutiny intellectually.

Two) The English Wikipedia on Morelli

The article, naming Morelli also a ›political figure‹, but speaking almost exclusively of Morelli’s contribution to art history, is redolent – directly and indirectly – of the Ginzburgian tradition and interpretation of Morelli, but not of Ginzburg’s later self critique, of which the authors of the article have not taken notice.

Thus the article does include all shortcomings of that tradition which had, like any other tradition, not put Morelli’s actual practices under scrutiny but simply assumed that what was understood (much too narrowly, but suggestively) as the Morellian method, was also practiced by Morelli and his pupils, that it, the method, did work, which is: did work successfully (although Morelli nor his followers, nor art historical tradition did show so convincingly).

Also the Ginzburgian tradition (much indebted to Edgar Wind) did – rather surprisingly – not miss a more or less lacking culture of verifiability in Morelli, although, nonetheless and thus also surprisingly, Morelli was or still is being regarded as a figure exemplifying an ›evidential paradigm‹ in the Humanities.

Thus the article, in its portraying of method and man, does present the typical suggestive simplifications, among which we might mention for example: 1) ›Morelli based his work exclusively on Morellian clues‹ (which he certainly did not, never excluding other connoisseurial tools, never excluding intuitive testing of painters personalities (or historical documents, if necessary), and regarding his own testing for certain properties as just one tool); 2) ›Morellian clues were to be considered as ›fingerprints‹‹ (while Morelli neither assumed that it was about stereotypical formula); or 3) ›Sherlock Holmes did, in his working, refer to Morelli‹ (which he certainly did not, relying on family likenesses as far as the comparing of shapes of ears was concerned and this even as far as the portrait in the Hound of the Baskervilles novel is concerned, and not on Morellian properties in painting, which rather are fit to distort the representation of family likenesses, in case a painter indeed – if he does so at all – imposes his inner notion of ear anatomy upon a portrait).

The simplified image of Morelli also did secure Morelli an not completely deserved status as the only rationally proceeding connoisseur with many apparent heirs also in the field of archaeology. While it is true that Morelli, remaining more or less silent as to other connoisseurs’s achievements that he was indebted to (for example Rumohr), made himself an advocate of scientific connoisseurship, but regarded a future Kunstwissenschaft as something that yet had to be established (and in our opinion never has been established at all in art historical institutions nor outside such institutions, lack of an vital culture of verifiability and falsifiability). But for the time being the image of Morelli is, also due to simplification, partly very vague and partly much distorted, and his connoisseurial methods and practices, albeit surrounded by a Sherlock Holmes-aura, often completely misrepresented and misunderstood (chiefly because they are not looked at at all and not studied at all, althought this is possible).

Adolfo Venturi Morelli certainly did not count among his pupils (on the contrary), although Venturi was befriended with Frizzoni and also payed, as a young scholar, Morelli a visit.

Finally: The article remains vague and rather in confusion as to any other dimension of Morelli’s biography, be it his doings during his studenthood and afterwards, his actual intellectual biography, the roots of his methods and practices, or his acting as a political figure (his involvement in the picture trade, also here, remains unnoticed). All in all the article can be considered, although the authors were obviously concerned with Morelli and also striving (unlike the above discussed article in the Encyclopædia Britannica) for precision, as representing the power of (rather theoretical) simplifications and powerful metaphors.

***

A portrait by Bronzino, perhaps to be associated with My Last Duchess

Robert Browning, Giovanni Morelli and Frà Pandolf

Morelli, who met English poet Robert Browning in Venice in 1883 (on left a portrait dating of 1882), met, according to his own words, a ›friend of Lermolieff‹. Which were apparently not Morelli’s but the poet’s own words (compare GM to Jean Paul Richter, 25 November 1883). According to Austen Henry Layard who had introduced Morelli to Browning (compare Layard 1900, p. 36), the latter enjoyed the conversation with Morelli and »pronounced his books to be amongst the most delightful and instructive that he had ever read«. Layard goes on to say that »Browning, from his knowledge of the early Italian painters and of their works, had some claim to be a judge«.

Layard, here as on other occasions, is obviously aiming at setting Morelli, the scholar, in the right light. But it deserves also mentioning something else, namely that two individuals did meet in Venice in 1883, who also might have found an understanding due to being inventive as to the creating of ficticious persona.

Morelli, on his part and as we do know well, invented various persona to speak for him, and above all Ivan Lermolieff. While Browning had, in his poem My Last Duchess (published in 1842), a Renaissance person speaking (»That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall / Looking as if she were alive. I call / That piece a wonder now«), and speaking also of a painter, who, according to the poem, was the creator of the last Duchess’ portrait. A ficticious Renaissance painter, in sum, named Frà Pandolf. Whose »hands« »Worked busily a day, and there she stands. / Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said / ›Frà Pandolf‹ by design, for never read / Strangers like you that pictured countenance […]«.

And one might wonder if not Morelli got indeed to know that particular poem by Browning in the following (which also does speak of a ›Claus von Innsbruck‹, another ficticious artist and creator of a ›Neptune, taming a sea-horse‹), since, as the speaker persona in Browning’s poem showed a rarely seen and usually hidden portrait to a stranger, Morelli was to stage (waggishly) a similar cult as to the painting later known as the so-called Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo (see chapters Interlude II and Visual Apprenticeship III), destined to be seen only by the chosen few, chosen by the portrait’s owner, that is: Morelli. A cult, less sinister certainly than that rendered by Browning, but turning, as we have also pointed out, after Morelli’s death into something like a sinister comedy.

(additional note: for Morelli and Carlo Emilio Gadda see Cabinet III)

***

(Source: Henning et al. (eds.) 2010, p. 290)

A very familiar tree (picture: Magnus Manske), the Abies nordmanniana,

named by and after Alexander von Nordmann, with whom Giovanni Morelli travelled,

in 1839, to the Atlantic coast of Normandy

Losing Touch and Keeping up Again with the History of Taxonomy

On the left we see – a young male blue shark. Caught at or near Naples in 1885, and prepared by scholars of the Stazione Zoologica.

This preserved specimen, today part of the collections of the Humboldt-University, was part of a 2010 exhibition on ›300 Years of Sciences at Berlin‹ (see Henning et al. (eds.) 2010) – and it does remind us, for example, of the history of zoological nomenclature (Prionace glauca is the scientific name of the blue shark), or of the history of taxonomy, and of Giovanni Morelli, who was 69 years old in 1885, being an (participant) observer of what was going on in 19th century natural sciences.

We have seen that he had been in touch with scholars of many disciplines as a student, and that, at Berlin in 1838, he even had had the chance to meet Alexander von Humboldt in person; but we have also seen that, in some sense, Morelli lost, as a student, touch with the natural sciences rather early, turning to poetry and literature instead, and this for several years (also cherishing a love-hate relationship with everything German, and with everything associated with Berlin very in particular).

Only to bring in, much later, after he had turned to art connoisseurships, concepts into the Humanities, into art history, concepts similar to concepts used in several disciplines of the natural sciences. Above all: the concept of type.

But still it does not seem to be that easy to determine if or to what degree exactly Giovanni Morelli was still trying to keep up with the natural sciences (probably as a reader of newspapers and more popular journals) in his later years. If, in sum, he actually was actually up to date – as to problems of classification, and how these were dealt with by contemporary scientists.

The 19th century saw a crisis in nomenclature, and the typological concept of specimen got also reworked and later, at least by some schools, dismissed, and replaced by other concepts (for a layman it is rather hard to survey this field, and I am declaring here to be a layman). Did this all affect Giovanni Morelli as well? Did he avoid a crisis in nomenclature? How does it look what he did to a today scientist (or a historian of science)?

No doubt, it is fascinating to read, or at least to try to read these various stories together (the history of scientific nomenclature and the history of connoisseurship), but we would also say that further research would be welcome, to place Giovanni Morelli not only into a history of the Humanities, but also into a more broad history of taxonomy, and particularly: the working with typological concepts (like for example – we again look at our blue shark – the notion of Typenexemplar/›type specimen‹).

On this abstract level, we imagine, it might also be possible to bridge the gap between various scientific cultures, and to observe how various disciplines dealing with natural or artificial form (or shapes) developed standards of classification, and how, very in particular, they dealt with problems of taxonomy (and also problems associated with the rather ambiguous notion of type and with reference material, reference objects, very in general).

What we also would like to annouce here is finally a new book by Michael Ohl which is called Die Kunst der Benennung, and deals with the ›art of namegiving‹ or the ›art of nomenclature‹ in the natural sciences (see Ohl 2015). This is something – although, or just because the author is not concerned with the Humanities at all, or even with art connoisseurship –, something to be recommended to a reader of our Giovanni Morelli Monograph as well.

***

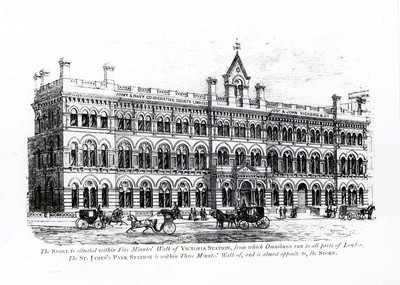

National Gallery (picture: Morio)

Army & Navy Stores in 1872

(picture: housefraserarchive.ac.uk)

Assyrian Reliefs from Nineveh

in the British Museum (picture: Mujtaba Chohan)

Christ Church College, Oxford (picture: Steve Cadman)

Chatsworth House (picture: Michael Parry)

Hampton Court Palace (picture: Andreas Tille)

With Giovanni Morelli in London

5 July 1887 (Tuesday): National Gallery with Jean Paul Richter and W. Koopmann; [probably] lunch in [Army & Navy] Stores (Victoria Street); [probably] British Museum (Colvin); Timoteo Viti drawings

6 July 1887 (Wednesday): early in the National Gallery with Jean Paul Richter; meeting also with Louise M. Richter, [probably: William Pitcairn] Knowles, [probably: Henry Edward] Doyle and Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes; dinner at the [Ludwig and Frida] Monds; music

7 July 1887 (Thursday): National Gallery with Jean Paul Richter; meeting with Frizzoni; two daughters of the Prussian Crown Princess seen; Stores for lunch; British Museum; Raphael drawings

8 July 1887 (Friday): [probably] National Gallery (Louise M. Richter, Henriette Hertz; Frederick Burton); British Museum in the afternoon; Raphael and Michelangelo drawings; drawings at [John] Malcolm

9 July 1887 (Saturday): getting (probably new or newly fixed) trousers; [probably] visiting Lord Bute at Chiswick

10 July 1887 (Sunday): visiting [Francis] Cook at Richmond with Frizzoni, Koopmann and Richter

11 July 1887 (Monday): departing at Hotel Almond to see Windsor; Royal Library and Gallery; being presented to Queen Victoria (see chapter Visual Apprenticeship III); meeting the Layards at about five o’clock; staying now with the Layards (1 Queen Anne Street)

12 July 1887 (Tuesday): in the later afternoon with the Layards

13 July 1887 (Wednesday): National Gallery with Henry Austen Layard

14 July 1887 (Thursday): with the Layards

15 July 1887 (Friday): National Gallery with the Layards, Lady Eastlake (wheeled about in a chair), Charles Eastlake (junior) and Frizzoni (Enid Layard sees the new staircase and new rooms for the first time); thunderstorm and hard rain; dinner with the Layards

16 July 1887 (Saturday): with Frizzoni and Koopmann to Oxford

17 July 1887 (Sunday): seeing [probably: William] Mitchell; also [probably: Eugène] Piot; again with the Layards; dinner

18 July 1887 (Monday): dinner with the Layards at Newstead Wimbledon

19 July 1887 (Tuesday): lunch at the Layards; dinner with Jean Paul Richter

20 July 1887 (Wednesday): Royal Academy with the Layards (Frizzoni and Koopmann there); National Gallery; seeing [John Charles] Robinson; at Hertford House with Jean Paul and Louise M. Richter, Charles B. Curtis and family; Stores with Jean Paul Richter; at Thibaudeau (Pontormo); National Gallery (Burton)

21 July 1887 (Thursday): with Jean Paul Richter to Lord Northbrook; dinner with the Layards and Lord & Lady Aberdare, 22 Elvaston Place

22 July 1887 (Friday): with Richter, Frizzoni and Koopmann to Oxford; Raphael drawings in Christ Church College (compare Baker 2001); University gallery

23 July 1887 (Saturday): unknown [perhaps Portsmouth; Queen Victoria is visiting Portsmouth]

24 July 1887 (Sunday): lunch with Frizzoni, Richter and Koopmann; travelling to Chatsworth (lodgings)

25 July 1887 (Monday): Chatsworth House; difficulties with getting to see the drawings; Venetian masters; Raphael; in the evening conversation in the park

26 July 1887 (Tuesday): Chatsworth; studying the drawings; Romanino; via Derby to St Pancras; [probably] at the Monds

27 July 1887 (Wednesday): British Museum; studying Jacopo Bellini drawings; later: etchings and bronzes

28 July 1887 (Thursday): with two carriages via Richmond to Hampton Court Palace; [probably] dinner in Langham Hotel (with Charles B. Curtis and wife)

29 July 1887 (Friday): National Gallery; later: discussing the [not extant] satirical essay Kunsthistoriker & Kenner with Jean Paul Richter

30 July 1887 (Saturday): at the Layards; Charing Cross; departure (and missing a Sarah Bernhardt performance as Phèdre in the evening)

(Sources: Jean Paul Richter, Diary; Louise M. Richter, Diary; Enid Layard, Journal; for Sherlock Holmes in 1887 see here)

(Picture: youtube.com; BBC1)

***

Go To:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | HOME

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Spending a September with Morelli at Lake Como

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | A Biographical Sketch

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Visual Apprenticeship: The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | Connoisseurial Practices: The Giovanni Morelli Study

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | The Giovanni Morelli Bibliography Raisonné

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH | General Bibliography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude I

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Interlude II

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY | Visual Apprenticeship III

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY:

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet I: Introduction

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet II: Questions and Answers

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet IV: Mouse Mutants and Disney Cartoons

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI STUDY | Cabinet V: Digital Lermolieff

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS