M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART ![]()

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Mona Lisa Landscapes

No, this is not about Giocondaclasm. We will navigate elegantly between the Scylla of Giocondaphobia and the Charybdis of Giocondaphilia, and only in passing by we will shed light on the Louvre picture commonly referred to as Mona Lisa. What we try to do here is to reinvent the visual essay, by exploring what it means to cross imaginary landscapes made of words and images. And in taking a detour to the poet Petrarca’s Canzoniere we’ll construct a bridge to an other, unfamiliar way of looking at the Mona Lisa nonetheless.

Mona Lisa Landscapes

(Picture: golfinginlasvegas.com)

(Picture: borghiditoscana.net)

Let’s start with a thought experiment. The picture on the right does show a golf resort. It may be by accident or not that this is a golf resort situated north west of the city of Las Vegas, but now we close our eyes and image a golf resort that is designed after the Mona Lisa background landscape. Do we all recall the rocks or mountains in the background, the »circle of fantastic rocks« as Walter Pater had it once, the middle ground with the bridge on the right (some refer to it as aqueduct), the curved road on the left? And maybe we do recall as well the sitter of the portrait commonly referred to as Mona Lisa, but for once we are allowed to think of the portrait as empty (and yes, a little bit of Giocondaclasm, conceptual art style, must be allowed) – as we imagine a golf resort’s so-called tee box instead. This is where our journey into unknown territory starts. Not nearby Las Vegas, but at our club and golf resort of choice, the Sahalee Country Club, nearby Seattle, at Hole 7.

Sahalee Country Club Hole 7 (North) (picture: golftripper.com)

(Picture: totallandscapecare.com)

Recent years have not only seen various attempts (or renewed attempts) to identify the Mona Lisa’s sitter, but at least two attempts to identify the Mona Lisa background landscape with actual places in Italy (see here and here). We do only briefly mention this here, because – without questioning the legitimacy of these attempts, and without questioning the legitimacy of an illustrated Mona Lisa background landscape atlas (we find this actually a charming and also a stimulating idea) – this is also about a fundamental asymmetry within our culture: While the picture commonly known as Mona Lisa does obviously represent art as such, painting as such, the portrait as such, fame as such or the Leonardo myth as such, and therefore is all present within our culture – our culture on the other hand dedicates little time as to attempts to take the Mona Lisa seriously as a work of art, asking for example why Leonardo, as an artist, did stage a portrait’s sitter the way he did. And if one does explicitly ask why Leonardo did contrast a portrait’s sitter with that rather unusual background landscape – our culture is inclined to shake its shoulders, saying, well, it’s just a portrait (and isn’t it to be thought as the embodiment of beauty?).

(Picture: joecarusogolf.com)

But a portrait is not a portrait nor a portrait. A portrait does show someone as someone. By staging, and in staging interpreting that someone as someone. By relating that someone to objects and things, to other persons, to social spaces and also to landscape. And by putting a someone into such a texture of relations a portrait does construct and suggest a view upon that someone. But how and to what purpose did Leonardo da Vinci do this in the Mona Lisa? If we stay dedicated only with identifying a sitter or a real landscape we might miss the Mona Lisa as a work of art. And this we find a pity. Because only by addressing actual artistic strategies – instinctively or more deliberately – one does actually relate to a work of art as such. Whereas the mere being obsessed with identifying sitter or landscape, as a consequence of the portrait’s prominence, might even prevent to take the Mona Lisa seriously as a work of art (beyond its significance as a ubiquitous symbol). As a work of art and as someone’s solution how to interpret a someone in a portrait. And not only of this someone’s identity we would like to know of more, but also of the artist’s strategies and also this strategies’ purposes.

(Picture: pasolinipuntonet.blogspot.com)

(Picture: n-tv.de)

We neither tend to an apotheosis of the Mona Lisa here (this we called the Charybdis of Giocondaphilia) nor to a young-Roberto Longhi style dismissal (the Scylla of Giocondaphobia), but the irony does not escape our notice that Italian local patriotism that tends to claim and to celebrate ›their landscape‹ as the actual Mona Lisa background landscape is fundamentally in opposition to Longhi’s position of 1914, i.e. of his declaration rather not to speak of this »paesaggio filaccioso e verdastro, questa piatta fantasia antartica«.

And back to the Sahalee Country Club (picture: snipview.com)

A Petrarchian Atlas

From an illustrated edition of the Canzoniere

What we would like to question here is the very idea that with the Mona Lisa we face a portrait whose mere purpose it was just to recall the visual image of a person, be it idealized or not. It’s the poet Petrarch who does show us that a painting or a poem can be about more than simply about that. And to realize what words can do, and what also a painting can do we have to enter Petrarchian landscapes of words, of words that also do recall visual things and also evoke the evoking of visual memories, stimulated – this is of particular interest here – by landscape, and by rough landscapes very in particular.

However it is not about making a case that the concept of the Mona Lisa was actually based on Petrarch and in particular on one of his poems. But this is about showing possibilities, possible artistic strategies that Leonardo da Vinci could have taken notice of or not. But the point is, even if he did not – and lack of sources we simply have no clues as to how Leonardo himself thought of the Mona Lisa – these strategies existed within the culture he did live in. And as a matter of fact these strategies existed since the 14th century.

It is the famous No. 129 from the Canzoniere we do think of: Di pensier in pensier, di monte in monte. And what we would like to do now is to take a walk through this very poem’s topography.

(Picture: parchiletterari.com)

A landscape by Shen Zhou, a Chinese contemporary of Leonardo (see also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shan_shui). In his classic Leonardo da Vinci-biography, originally published in 1939, Kenneth Clark wrote: »[…] so the resemblance of his [Leonardo’s] mountains to the craggy precipices of Chinese painting is no accident, for the Chinese artist also wished to symbolize the contrast between wild nature and busy organized society. Yet between Leonardo and the Chinese there is also a profound difference. To the Chinese a mountain landscape was chiefly a symbol, an ideograph of solitude and communion with nature […].« (p. 175) Whereas, as Clark goes on to point out, Leonardo saw landscape like a part of the whole organism of Nature that had to be understood in its parts but also as a whole.

We take a walk, and we are entitled to take a walk because the lyrical subject of the poem is taking a walk (through actual, imagined or, if you like, textual landscapes). Haunted by memories of his loved one, and also in love, we assume, with his obsession for these memories. In any rate it is also a poem about being obsessed with memories of a loved one lost. And that the lyrical subject likes being obsessed with those memories, although in a state of unrest and not knowing whether to enjoy this or to suffer, we are shown by the simple fact that the lyrical subject does flee the crowded streets and paths and strives for more deserted landscapes, where there is peace and quiet, where there are no other faces around, and where the visual memory of his loved one, as we will see, haunts him and re-appears (whereas within a crowd this would probably work less well). In sum: the being haunted is, if not only pleasant (and the lyrical subject knows that it is not only pleasant, because of the re-disappearing), for the moment wanted. And the more deserted the landscape, the better this works. This is why, as we see now, the lyrical subject also flees the Locus amoenus-landscape of the first verse (compare the picture above) and, in the second part of the Canzone, does climb high mountains.

We are now told that the lyrical subject, looking back at society from deep forests and high mountains, most deeply hates all inhabited places. And on every step the lyrical subject is now being haunted by mental images of his loved one lost. It is bittersweet suffering now, and »almost«, the lyrical subject says, almost one would want this to go on. But he (or the lyrical subject) does remind himself/itself that Amor could also still provide for better times to come. And now, for a moment, there is only doubt: How could this be? And how? And when?

Instead of following this path laid out by his inner voice the lyrical subject does now start to paint: mental images of her beautiful features, images that might be called mental images, but the poem speaks of the lyrical subject’s painting on the rocks. And now the lyrical subject is a bit frightened of itself. The subject knows that seeing the image is only illusion, but to disturb the illusion the subject does not want (and neither to analyze its state of mind and its future options), and while being doubtful about its own state of mind, the lyrical subject praises the illusion (be it only for as long as it is there).

And now a verse that already does look back upon a history of being haunted by mental images (but who may trust the lyrical subject now?, the voice of the poem says, giving a hint to the reader or listener). Often I did see her, in clear waters, on green meadows, in a grove of beeches (instead of a tree) and in a white cloud. We skip the Leda passage and come now to the passage where Petrarch summarizes what is going on, in terms of a landscape and a lyrical subject interacting. We leave the Locus amoenus behind, and also the grove of beeches, because here Petrarca reveals, as it were, the formula, the algorithm of the being haunted by visual memories. Or better: he now makes it clear how this relation between landscape and mental images works (because he has already said it before): The more wild the landscape (and this is the moment to think back of the Mona Lisa), the more beautiful his awake dreaming does depict or paint her (as a mental image). And the lyrical subject and Petrarca know that this is about illusion. But about illusion that is a result of a wild landscape and a mind in unrest interacting. And although the poem shows various landscapes, here it does show the extremes: the more wild the landscape – the more beautiful, and this is the artistic strategy that a painter might be interested in to adapt for his purposes. We give the most interesting passage as to this relation here (and we do note that the beautiful German translation provided by Bettina Jacobsohn does explicitly speak of »painting«, while the more sober English translation given on the left chooses the word »depict«, if speaking of the illusion of a portrait of a loved one lost:

and the wilder the place I find

and the more deserted the shore,

the more beautifully my thoughts depict her.

Then when the truth dispels

that sweet error, I still sit there chilled,

the same, a dead stone on living stone,

in the shape of a man who thinks and weeps and writes.

(English translation by A. S. Cline)

Je wilder das Gestein,

Die finstre Schlucht, je öder das Gestad’,

Je schöner malt sie mir mein waches Träumen.

Kommt Wahrheit fortzuräumen

Den süssen Irrtum, sitz’ ich kalt und matt

Wie toter Fels, im Leben schon versteint:

Ein Menschenbild, das sinnt und schreibt und weint.

(German translation by Bettina Jacobsohn)

et quanto in piú selvaggio

loco mi trovo e ’n piú deserto lido,

tanto piú bella il mio pensier l’adombra.

Poi quando il vero sgombra

quel dolce error, pur lí medesmo assido

me freddo, pietra morta in pietra viva,

in guisa d’uom che pensi et pianga et scriva.

A painter interested in the visual potential of this textual strategies might stay focussed on this very passage quoted above, in its crystallizing of a fundamental principle of contrast. But the poem and the lyrical subject do take us now to the even higher mountains, i.e. to the one summit to which there is no shadow of another mountain raising. And again: how close, the beautiful face, but also how distant. – And now the question: What are you doing, poor creature? Whereever she might be, maybe she did sigh as well because of our being seperated – and this is the very thought that means comfort to the mountain climbing lyrical subject being in such unrest. And the lyrical subject ends with speaking, surprisingly, to its song itself: Beyond the Alpine chain of mountains, Canzone, you will find my true image – under the laurel tree, there is my heart, and there is also she, she who did take it from me.

Landscapes of Obsessions

We have spoken of Mona Lisa landscapes, and although we have tried to make it clear from the beginning that this is about the background landscape of the Louvre painting commonly referred to as the Mona Lisa, the very term can of course be understood in its meaning (or subtext, or double sense) of bodily landscapes (referring to the very portrait’s sitter). Who is creating this subtexts? Is it language itself? Is is the subject writing, possibly entangled in what one may call the potentialities of textual sense? Or was this wanted from the very beginning?

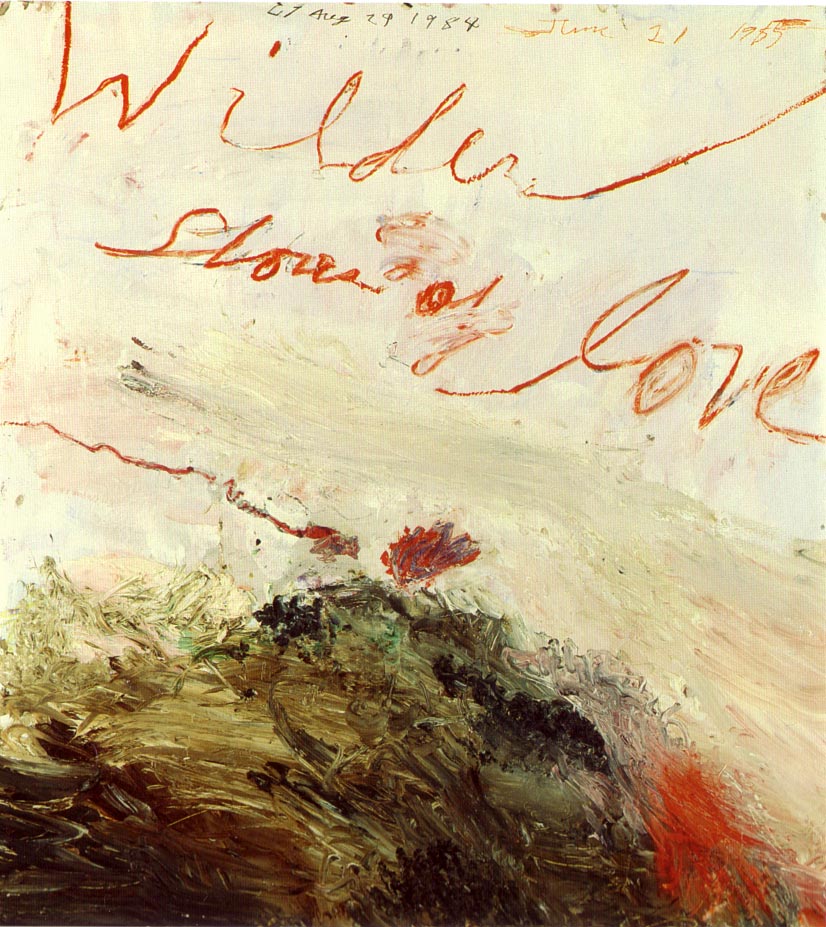

In any rate we did encounter landscapes that obviously do not only speak of, but also are loaded with obsessions. And I don’t know if Petrarch scholars think of the Canzoniere as being free of bodily subtexts, although this is not obvious at first sight. The language of obsessions may turn actual landscapes of nature into bodily landscapes, and of course likewise the inverse way. If we think of other works of art, of Cy Twombly’s Wilder Shores of Love for example, that might be interpreted as landscapes of obsessions, we realize only too soon, if we take a brief look into Cy Twombly criticism, that what we encounter is exactly this kind of metamorphosis. I have never thought of Wilder Shores of Love as a representation of flesh, of sexual organs, but others people obviously have. Be it as it may: what I do find interesting about this painting in our context is the atmosphere of exuberant nature, of animality, if one likes so, but we also do find these signs of obsessional unrest, of nervousness, familiar after our encounter with the poem by Petrarch: the lyrical subject expressing its doubts (in its incessant self-questioning, its self-correcting), and falling from one mood into another, from one grand gesture (note the grandeur of the scripture) into depression (note the hardly-hidden, or even ostentacious self correcting as to the position of the word »of«).

But it is the whole field of Mona Lisa studies that might be seen as one large landscape of obsessions, full of these language phenomena, and we only remind of recent attempts to identify the sitter for the Louvre painting as a prostitute. But it is also remarkable that one rather official interpretation of this very painting, one of the rare interpretations, by the way, that takes also the background landscape into account, speaks of the painting as representing the victory of virtue over time. No bodily landscapes here, only resistance and chastity, if one may say so frivolously, but one couldn’t say that this would be the common interpretation of the Mona Lisa, if only for the fact, as we mentioned above, that what is allknown is not the work of art, but rather the symbol (for whatever).

Which is one of the strangest facts about the Mona Lisa – because for one: every signifier might be replaced by another signifier (and this is what for example Roberto Longhi tried to do: to recommend a replacement of Leonardo’s Lisa by Renoir’s); and for two: the Mona Lisa has not always been a symbol for whatever (which means: there is no necessity for the painting to serve that function, only contingency there is, and contingency means non-necessity). There were times that the painting commonly referred to as Mona Lisa was rather unknown and little noticed. In sum: be it for the interpretation of the painting itself (not as a symbol but as work of art), or be it for what you consider as the embodiment of beauty, fame, art, portrait etc. – in the end it is about taking your own personal wellfounded pick.

Landscapes of Obsessions: Wilder Shores of Love by Cy Twombly… (picture: micasaesmimundo.blogspot.com)

…and the virtual redoing of ageing by technical means (picture/source: lumiere-technology.com)

(Picture: bologna.repubblica.it)

(Picture: goldsteingolf.com)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS