M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Seeing Right Through Someone  |

See also the episodes 1 to 9 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

And:

Seeing Right Through Someone

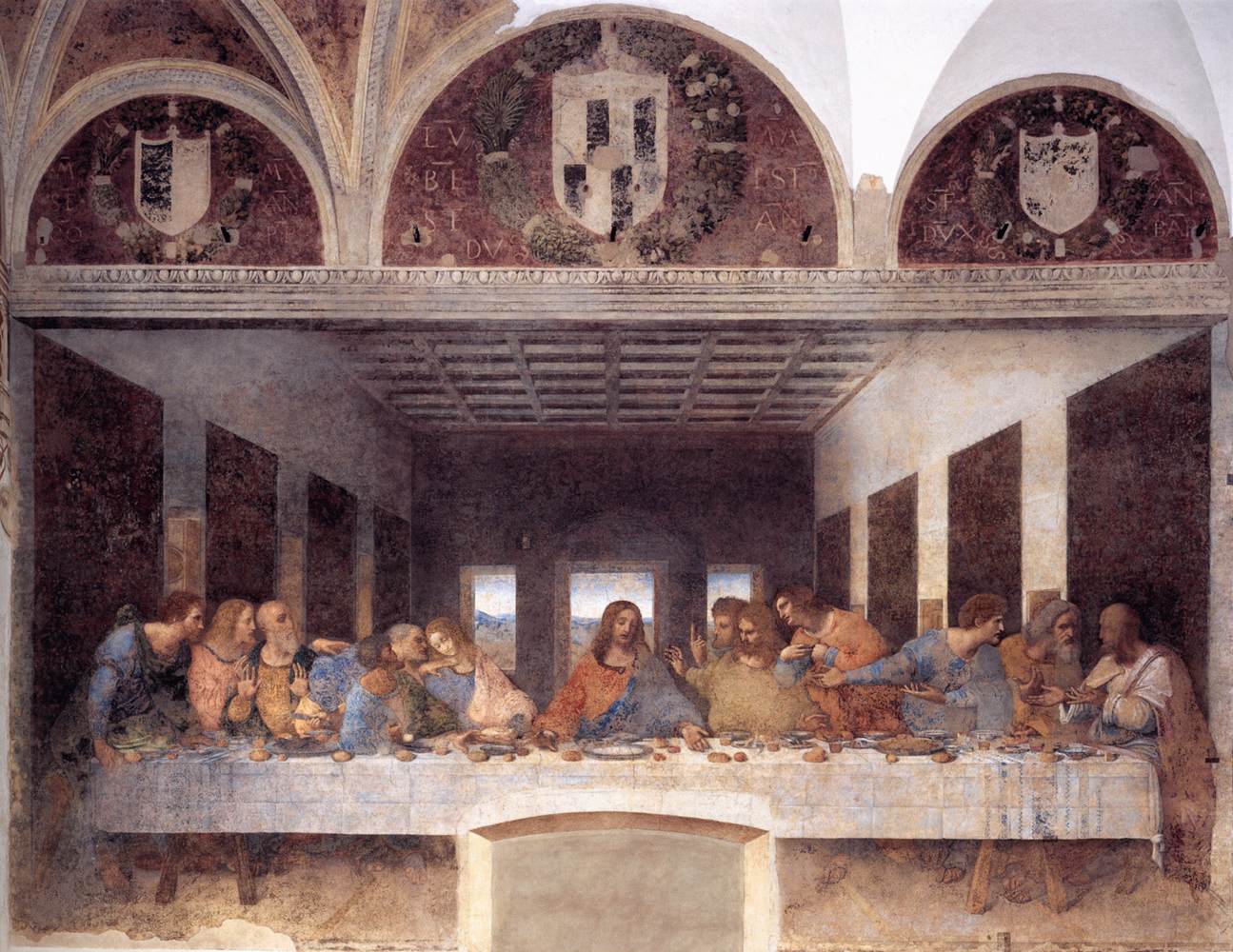

(24.7.2021) Where are we, if we are visiting Santa Maria delle Grazie? In a cloister of the Dominican order.

Where are we, if we are visiting Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1495? At the place where Leonardo da Vinci is just about

to create the iconic image that about 500 years later Martin Scorsese was to insert into the background of a sequence

of his 1990 gangster movie GoodFellas (let’s say as a symbol indicating that all that happens in this particular sequence does

happen within a Catholic, or supposedly Catholic context, for which The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, in whatever

form of reproduction, does stand; for a screenshot see below).

And (as we do now seem to know): At the place where Leonardo da Vinci probably just had created the design of a Christ

Blessing, preserved by the painting of another artist, a design that Leonardo was to develop, (probably) after having

created The Last Supper, into a Salvator Mundi design, which, also about 500 years later, does stand for, well,

perhaps materialism. But, as a basic design, had been developed within the context of a Dominican cloister.

Readers of my New Salvator Mundi History perhaps may think that I think it to be my mission to turn the notoriously

famous Salvator Mundi (that does stand so beautifully for materialism) into a museum of European History. Well, this was

not my idea, nor it is my mission. But what I would like is the idea that my history might help to establish an

alternative perception of this particular painting. A perception that indeed would insert this painting into a panorama

of European history. And yes, those readers who have been following the trajectory of my history from episode one to this

episode ten may indeed have the impression that this painting perhaps not only is a symbol for materialism, but an object

that indeed can be placed into a panorama of European history, and that it might be even rewarding to see it as an

object than encompasses history, because this object is fabulous in making history alive.

Hence: Why not thinking of the painting (which is of a hybrid quality, partly mediocre, partly brilliant, as a work of

art) as the heart of a Museum of European History (and art)? Why not turning it into an embodiment of European history?

In one word: why not thinking of it as European history in a walnut (panel)?

At any rate: we will go on to explore also various contexts of history here. And this episode ten, which is also a sort

of interim conclusion of our history, as written from episode one to ten, is about something absolutely fundamental: it

is about the gaze of Christ, about a gaze of Christ meant to exist in a Dominican context, where, for mysterious

reasons, it was probably not brought to existence (why not?); and this episode is also about what may have happened to

that gaze and to that Dominican context (lost in history). In these lines (or at least between the lines) you will

also find my answer to the question if the Salvator Mundi can be considered as being the ›male Mona Lisa‹ or not,

respectively the answer to the question if such analogy does make sense at all, and if yes, on what level (pictures

above/below: Hermitage Museum; Good Fellas DVD).

One) A Gaze

One misunderstanding should be avoided: I am certainly not claiming that the Christ Blessing of the Hermitage that I am

going to further discuss here, is by Leonardo da Vinci. What I am assuming is that this Hermitage painting (presumably by

Paolo da San Leocadio) does preserve a design that Leonardo da Vinci had prepared to be realized in and for the Dominican

cloister of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Let’s say that he had prepared two designs for the prior and the monks to choose

from, a Pietà and a Christ Blessing. And let’s suppose that the cloister wished the Pietà to be realized. The cartoon

against which the cloister thus may have voted, still got realized, but by another (visiting) artist: as I am supposing

this (actually Spanish-based) artist might have been Paolo da San Leocadio.

All these hypotheses should be questioned as fiercely as possible, of course. But I have actually little doubt that the

Hermitage painting does preserve Leonardo’s ideas quite well, and I have two reasons for having little doubt: the first

reason is the elegant and intelligent interplay of hair and ornament. The pictorial intelligence that did come up with

this interplay reminds me of the pictorial intelligence that did set the hair of a woman against a juniper bush – in the

portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci.

The second and main reason is the subtlety of the gaze of Christ. And others may have understood this long before I did,

but I did understand it only now and with this picture: Christ is neither cross-eyed, nor does he look through the

viewer, as if not recognizing him or her – Christ is staged here as seeing right through whoever might look at him.

This is a very subtly staged eye contact that we have with this representation of Christ, who seems to look at the

viewer, but actually seems to focus rather on something in or even behind the viewer, and this also gives the idea of

Christ being slightly cross-eyed. But this gaze must be exactly what the artist who conceived this gaze must have had in

mind, because this is exactly how Saint Dominic thought of Christ (and of what faith is). Because at the beginning of the

Dominican order is the idea to devote oneself to those who have lost their faith in the church, but not their faith in

God. Saint Dominic as devoting himself to the Cathars, thought these as people that could be brought back to the

Church. He – his gaze – had spotted people who had lost the right path – but could be brought back, since God does not

turn away from anyone – there is no hopeless case. The blessing of Christ, thus, is indicating that, whoever has lost the

right path still has the chance to come back. But the gaze of Christ, here, also has incorporated this Dominican gaze of

having spotted people who are not living in accordance to what God does want (according to the perception of the

Dominicans and their intellectuality). And it is the Dominican mentality (and the artist who is conceiving such design

for them) that stages Christ as seeing right through anybody – the Cathar, the sinner or the viewer, whoever he or

her might be, all-knowing, and indicating that there is the chance for everyone of being blessed. But also indicating that

there is control and assessment of the way people live. According to the right faith or not. This Christ being an

embodiment of the Dominican idea of devoting oneself to people, of searching, spotting, assessing, controlling, bringing

back and – alas – also of represssing those who do not live in accordance to the right faith, was conceived by a master

artist. And this Christ also raises the question if any Dominican monk who was meant to live with such design on a daily

basis did like this idea of being seen right through all the time. Who would be surprised, if people voted against being

measured every day, or being reminded everyday that everybody is being measured constantly by God’s all-knowing gaze. This

picture stages, potentially, a rigidity of being watched in every aspect of life, a rigidity of permanent control and

desirable self-control, that certainly not every and each Dominican was ready to vote for. The artist who conceived this

must have been an extremist, not a fanatic in faith, but an extremist as far artistic consequence is concerned. This

gaze is a Dominican gaze. And this Dominican gaze is at the beginning of the Salvator Mundi saga, and nothing else.

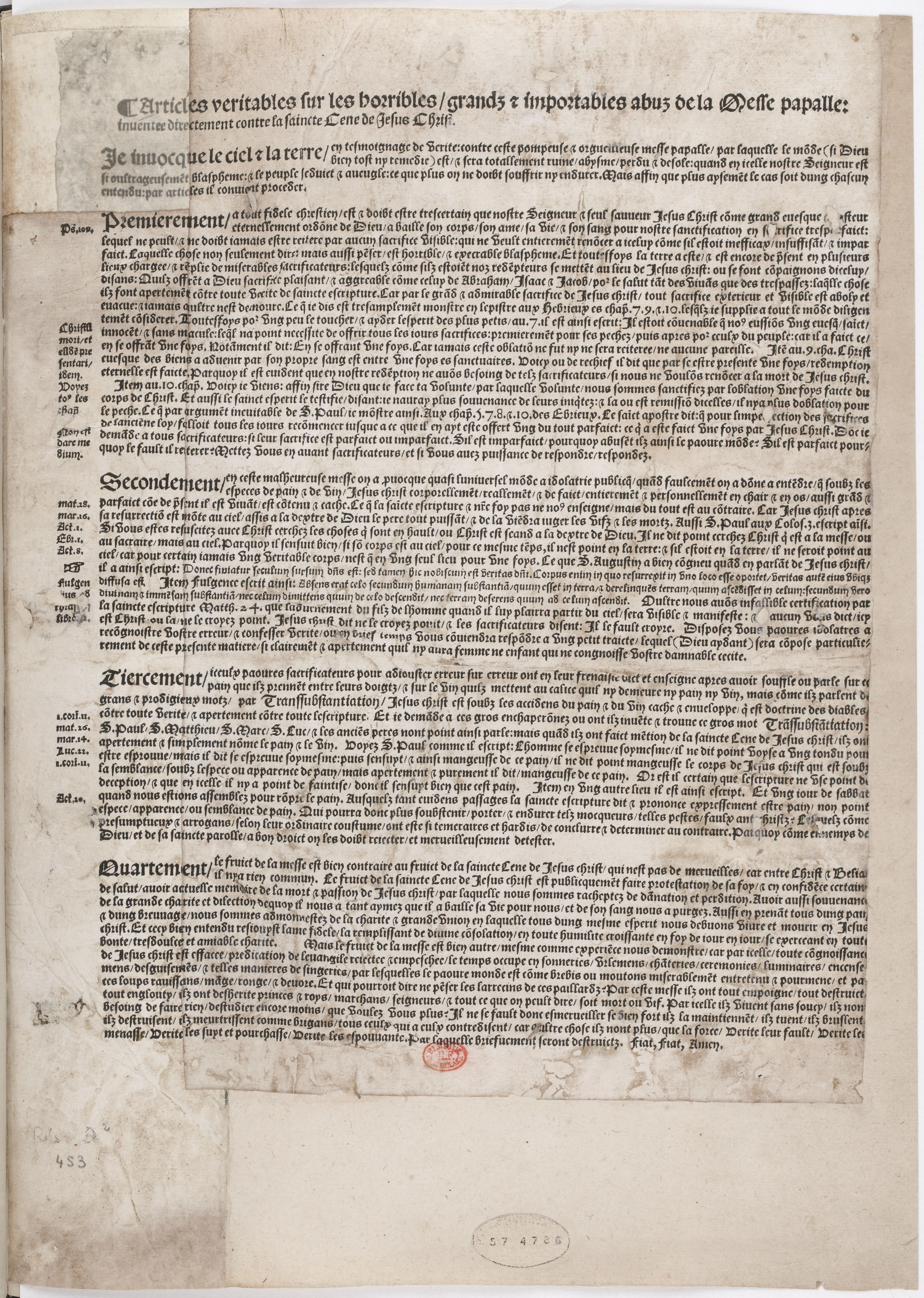

Two) A Dominican Context

Where are we if we are visiting Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1495 with Paolo da San Leocadio? Well, Rodrigo de Borja,

now pope Alexander VI (pope since 1492), had been his patron. And Paolo had settled in Spain as an Italian artist being

recommended by the (then) cardinal. And Paolo must have been only too-aware of what had been going on in Spain in 1492.

Most people are used to think of Columbus first, but we should think here of the expulsion of the Jews, of the Spanish

inquisition and of Tomás de Torquemada. If we are visiting Santa Maria delle Grazie with Paolo da San Leocadio, we are

visiting a cloister of the Dominican order with a man who was well aware of the climate that the Dominican Tomás de

Torquemada, that the Catholic rulers of Spain had established. It is no coincidence that the painting by Pedro Berruguete

that we show here below, had been created in these very years (the exact date not being known); but it is this painting,

staging an auto-da-fé being presided by Saint Dominic that Henry Kamen chose as the cover for his study on the Spanish

inquisition. We should be aware of this context, of the Dominican context of this picture of Christ preserving probably

a design by Leonardo da Vinci that is at the beginning of the Salvator Mundi saga.

But what happened afterwards? Well, let’s make a big jump first. Because the later end-16th century versions of the

Salvator Mundi, the Fontainebleau group (or the ›Northern‹ group) as I am calling them, did preserve the gaze of Christ

as being described above (and also the Hollar etching). But the notoriously famous version Cook did not. Of course it is

all the time being compared with the Hollar etching and other versions, and it is easy to imagine ways it may have

looked, even if we don’t seem to know for sure. But as regards the eyes we see pigment loss in the version Cook, and

these pigments have not been renewed. It has been quite easy to project all kinds of ideas into this painting, and to

stage it, hypothetically next to the Mona Lisa. But what about the gaze of the Mona Lisa. Is this a Dominican

gaze as described above?

I would describe the gaze of the Mona Lisa as the gaze of a slightly melancholic woman who has just been cheered up a

little, for example by seeing her child play. I see warmth and a loving gaze, and I don’t see the rigidity of permanent

control (and potential repression by self-declared followers of Christ), and I would not hesitate to confess to the Mona

Lisa that I have eaten all the sweet plums. But the idea of control and repression that, if Dominicans like it or not, is

being associated with that order – due to the dark side of its history –, this idea I do not like. And I don’t see why we

should be juxtaposing the Salvator Mundi and the Mona Lisa on any level.

The mother of the gangster we see in the screenshot from GoodFellas below is also seeing through her son, but with a

mix of fear, sadness, helpless love, all being disguised in seeming naiveté. She sees clearly (at least I would say) that

her son has lost the right path, and the vaguely perceptible but all-known Jesus Christ in the background, is one of the

two other representations of Christ Leonardo created for Santa Maria delle Grazie. Scorsese staged a diner in front of

The Last Supper, with an additional ballet of hands (and a knife, ketchup and so forth), on the right side the thumb

of Robert De Niro, and for some strange reason, we see, with the gaze of the mother, someone seeing right through

someone (her son), just as the Blessing Christ was meant to see right through everyone. The Dominican context of the

Salvator Mundi got lost, but it is in the genes of our civilisation that wherever we see sin, we see and stage also the

measuring of sin, control (if still possible), and yes, we stage repression of sin, and we have never lost the metaphor

of the right way.

Three) An Interim Conclusion

I have described, in episode nine and now in this episode ten, what I see as the formation conditions of the Salvator

Mundi design. It all happens in a Dominican context. And I have made a big jump to what I am calling the Fontainebleau

group. But what happened after the design of the Blessing Christ had been created and, as we see, been realized for

the first time – but by another artist and not by Leonardo, what happened after that?

I am assuming that, with all the Salvator Mundi versions, we see the collective biography of Leonardo’s workshop. We

don’t know the conditions yet under which the Blessing Christ was turned into a Salvator Mundi. But it did happen. And

after this had happened, it is more easy to imagine what happened: even if Leonardo never realized the design fully

himself (which is what I believe), even then it must have made sense to have virtually everyone of his assistants realize

a version. And this for two main reasons: first of all it must have been a way to assess the accomplishment, the

diligence and the creative potential of every assistant, and to compare their performances just as we are comparing their

performances (one might also think of a sort of ›exam‹ picture). And secondly: because pictures of Christ must have been

a frequently demanded subject, it must have made sense on a commercial level. Thus we have to work towards a collective

biography of the Leonardo workshop, as well as about ways to conceive such collective biography. And this is what we are

going to do in the next episode of our New Salvator Mundi History.

Selected literature:

Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition. A Historical Revision, New Haven/London 2014 (Fourth Edition)

1495: At around this date Leonardo da Vinci is supposed to have begun The Last Supper. Giampietrino is documented as an active painter.

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

The 15 November 2017 inscribes into the chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie as well (pictures: youtube.com / Christie’s). Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers as well as the Salvator Mundi have their roots in the Milanese cloister. And there is something else: While the Salvator Mundi might mark the beginnings of serial production of paintings at the time of the Renaissance, Warhols work does practice and selfreferentially comment on serial production and on viral images (it had been a commission by an art dealer; see here). Does it also comment on the Salvator Mundi? How would Warhol have commented on the Salvator Mundi saga? Would he have created Sixty One Plus Salvator Mundi Versions? Perhaps he might have thought or said: why underestimating Leonardo? he did in fact invent the multiple. And perhaps Leonardo was even more furbo than anyone ever imagined – perhaps Leonardo did also invent and practice the selling of serial productions as (more or less unique) originals, each of every member of a series. Do we have a category for such objects, or do we still have to find one (even if just the Salvator Mundi version Cook might have been a gift and not a commercial product)?

See also the episodes 1 to 9 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS