M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

SPECIAL EDITION

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Some Salvator Mundi Variations  |

A little satellite to this fall’s Leonardo show in the Louvre. And yes, we also have a little virtual museum (see below on the left). Is it a museum of ex-Leonardo pictures? Or a museum of confirmation bias? Not exactly, but perhaps in some way. We continue to look at and to reflect upon the Salvator Mundi controversy. And this is, after our page on provenance, and after the ›Microstories‹ and the recent ›Afterthoughts‹ (for links see below or check the sidebar) episode four of our own little Salvator Mundi saga: Mysterioso assai, or in other words: here are our Salvator Mundi Variations (begun August 28, 2019).

Codex Atlanticus 864r and the Salaì Christ of 1511:

In c. 1513/14 Leonardo reused a sheet that apparently already had a sketch of an eye and swinging curls of hair on it (picture: leonardodigitale.org). He reused that sheet upside down, and the floating text around the sketch has nothing to do with the drawing. So one might say that, in c. 1513/14, he still respected that drawing (at least the eye), since he avoided to write on top of it; but it was something from the past, the more recent past or the yet more distant past. But what was it? Or in other words: had it something to do with a Salvator Mundi (as some scholars, following a suggestion by Pietro C. Marani, think), or with a pupil’s picture that Leonardo did supervise?

We think that the best match is with the recently rediscovered picture of Christ by Salaì, signed and dated: 1511. And if you disagree, we would be interested to know how you manage to rule that possibility out: the possibility that this sketch on CA 864r reflects Leonardo’s teaching (and not Leonardo’s preparing of an autograph Salvator Mundi picture).

Start looking at the right corner of the eye: the hair swings as in the Salaì Christ. In the Salvator Mundi it swings in the opposite direction.

Comeback, (A belated):

Yes, also one particular Salvator Mundi might still have a belated comeback: The real important guests arrive late at the (Louvre) party. (But also guests with large egos, and also aging stars with huge self doubts). – – –

I am speaking of Boltraffio; and it is not without irony that this particular assistant (or whatever he was in relation to Leonardo) has a spectacular comeback in 2019. Almost unnoticed however, since the name Boltraffio is presently fit to scare the establishment. If the Salvator Mundi that presently everybody stares at is indeed largely by Boltraffio, almost the whole Leonardo establishment was simply dead wrong.

What I am getting at is that Pietro Marani has recently reattributed the superb Royal Academy’s copy of the Last Supper. To Boltraffio. And in Boltraffio’s biography (that no one attempts to write, since we hardly know anything with certainty), there is plenty of space to put all kind of pictures in. There is even space for a gloomy and dark phase. And with some imagination we might be inclined to put the Salvator – with the Columbia museum’s ›Scorpio woman‹ in there. Anyway. What exactly did Boltraffio do in the, say, last ten years of his life? We simply don’t know.

Now the Louvre seems to tell us that there is also more by Boltraffio in works that are (or have been) attributed to Leonardo. The face of St. John, for example. Who would have thought of that? But which one do they mean? – The London one.

Ah, the old problem of the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks, also a tale of two cities, London and Paris. How much Boltraffio in there (the London version), and confused with Leonardo’s hand? And the Madonna Litta? By Boltraffio, or by another pupil/assistant/friend/collaborator?

And La Belle Ferronière. Like virtually all Leonardo-attributed paintings a problem painting (that certainly the Louvre is not particularly keen to question).

We might be inclined to say that everytime Leonardo has a comeback year, Boltraffio has one as well. But it has already become a parallel tradition that the establishment is scared by this name. Haunted by a ghost named Giovanantonio. To be continued.

ps: the real question is not if the blue Salvator Mundi has a blue-hour-comeback in the Louvre (I guess it will, but a belated one, since the saga does now require such…). The real question (for the few conoscenti) is: will the Vierge aux balances be in the Louvre show. Since: Who needs Salvator Mundi, if you got Vierge aux balances (see below).

ps2: I forgot to mention the Musician which is also a notorious Boltraffio-related problem picture.

ps3: note that the Vierge aux balances is also Boltraffio-related. In other words: also Boltraffio used this Madonna head type, but realized it in the individual Boltraffian way. The author of the Vierge realized it in his (or her?) way. Which resulted in the mother of Christ looking as if literally being the mother of the Salvator Mundi Christ.

Confirmation Bias (yet again):

It cannot be said often enough: In attributional debates it means little if it is said that something is »consistent« in style with something else (e.g. the Salvator Mundi is consistent with Leonardo’s style in the time period x). And it means everything if beyond reasonable doubt it can be shown that something is exclusively consistent in style with something else.

It is not enough to silently imply the latter, because what is needed in rational debate is to know who compared a work in question with what. It can be (and we think it is almost certainly the case here) that the Salvator Mundi has not been compared actively enough with works by the Leonardeschi. Because it is a common misunderstanding that to find out if a painting is by Leonardo, you only have to look/stare at works by Leonardo that are unquestionably by Leonardo. No, if a debate is about the question if a work is by Leonardo or another Leonardesque painter, we have to compare with both sides, if we want to avoid or limit the problem of confirmation bias/verification bias (often enough, it goes without saying, exactly this kind of bias is fiercly wanted, but serious scholarship has to avoid it).

In several (perhaps not all) aspects the Salvator Mundi is »consistent« with work by the Leonardeschi. And, again, to say this means little. And what counts most is, after comparisons with all classes of works in question (autograph Leonardo pictures and Leonardeschi pictures), the exclusive identifier, and the transparent and systematic proof that this identifier is exclusively found in a work in question and another work (or another class of works) that serve as a reference.

And if this kind of identifier would be lacking: why deciding at all, if something cannot be decided? Or in other words: we might bet or speculate, but serious scholarship has to leave questions undecided, if no sufficient basis for decision can be found. (Speculative or only intuitive opinion-giving that all too many art historians seem to confuse with serious scholarly thinking, is, by strict scholarly standards, nothing more than suggesting hypotheses; not useless, but not enough, since it is the task of scholarship to move on from hypotheses towards well-reasoned certainties; and while or better: before moving on towards (wanted or unwanted) certainties, we should be aware of the problem of confirmation bias, since this awareness might mean that we are able to deal with that problem, allowing that awareness to regulate our acting and to compare on both sides, the wanted and the perhaps less wanted one.

On the left the Leonardeschi cabinet from our virtual Louvre show: two loans (the Columbia museum’s ›Scorpio lady‹ and the Salvator Mundi), appropriatedly grouped with the Louvre’s own Vierge aux balances.

On the right the autograph stars from Leonardo’s late work. (This grouping does not reflect any certainties – I would not be claiming that –, but a working towards such certainties that takes into account the problem of confirmation bias; for our reasons see my Salvator Mundi Microstories and particularly my Salvator Mundi Afterhoughts).

Detroit Desaster, The:

As historians we have learned to ask the question: who exactly was it who did built the pyramids? And: Who exactly was it who fell the tree? In 1569.

Well, we don’t know, but 1569 is now the date. The date the tree was felled, of which the panel was made, on which the Detroit Salvator Mundi version was painted (see new and well done website by Dianne Modestini).

What does this mean?

This means among other things, that Detroit is an total and utter desaster for connoisseurs: Since the Detroit museum details who said what and when on that painting, we have to draw the consequence that everybody was wrong. Not most of them. Everybody. Hundred percent. Or, to give a few illustrious names, Bernard Berenson, Federico Zeri, Wilhelm Suida and Ludwig H. Heydenreich. The painting is after 1569. And no one saw it, guessed it or knew it. Dendrochronology had to tell it.

But what consequence is there to draw from this?

First of all: The museum (who did not reveal the results of testing) has not yet drawn apparent consequences. We still see a Giampietrino attribution (which was the most frequently cited name, one of several names now proved wrong).

The second consequence would be to rethink methodology (but this is so out of date that no one would ever think of that, since New Art History has virtually erased all deeper connoisseurial knowledge as to method and practices since the 1960s).

The third consequence is therefore the one I have drawn in the beginning. Detroit is a desaster for connoisseurs. Pity, since the picture is actually quite good. Perhaps not superb, but good. And it belongs into the group with the (almost unknown) Versailles version (now in private hands) and with the Warshaw version. And probably the Zurich version plus satellite in Holkham Hall (to which we have pointed earlier). On which basis were they done? We don’t know either, but it seems that there was a Salvator Mundi bird-nest in France, in the second half of the 16th century.

ps: the Neue Zürcher Zeitung am Sonntag recently used a picture of the Detroit version to illustrate an article on the saga of the most expensive painting in the world. Does it matter? We don’t know. But it seems that connoisseurship does not matter much today.

Karl Raimund Popper (1902-1994)

Gombrich, Popper, Kemp (and Bambach):

It is interesting to look at the Salvator Mundi controversy from a methodological point of view. And at the same time it is frustrating to look at it that way.

This said: it is well known that Martin Kemp champions Popperian falsificationism. To his credit I want to stress that he is and was the only scholar who actually has a declared methodology as regarding attribution. Every other scholar apparently has not, or has not declared it.

Popperian thoughts are indeed a reasonable point of departure. This is about the basics of scholarly method and thinking and how such basics can be applied in the field of attribution (which was not exactly Karl Popper’s concern, although he also was interested in the arts, and beyond that, was also a friend of Ernst Gombrich, who perhaps can be named as having inspired Martin Kemp to adopt and to champion Popperian falsificationism, or the philosophy of Critical rationalism as it is also named).

Again the question to other participants of the Salvator Mundi controversy: Are you all critical rationalists? Or what are you? Anarchists in the spirit of Paul Feyerabend? Or unreflected, without declared methodology, but still apparent predilections? Is this a power struggle or a scholarly debate?

Methods of attribution can very well be reflected. But it is tiresome to remind professors and curators that scholarly thinking is about hypotheses and about proceeding from hypotheses to certainties. About the ways to get there. And about declaring it and not about to be silent and hiding the principles. Mere opinion-giving is mere producing of hypotheses, a starting point and not more than that.

Now – it is no secret that I think the narrative that is the basis of the Salvator Mundi attribution to Leonardo da Vinci as untenable. As about to be falsified. And we are back with the issue of falsification.

Since we are presented with the full documentation only next week (today is October 19, 2019), we will only see then, how intensely the falsification work had been with the Salvator Mundi. Brief: if Popperian falsificationism had not only been championed but also practiced. How, when and why have other attributions been ruled out? If we will find little of that, it will become fact that the attribution to Leonardo was the result of excessive confirmation bias. The outcome of an atmosphere that wanted something to be true. And this would exactly be the opposite of Popperian falsificationism.

Leonardo Expert, A Brief History of the:

(this history, for more or less obvious reasons, has to be done in fragmentary style)

1) As there are shadow secretaries (e.g. shadow Brexit secretaries) there are also shadow Leonardo experts. Carmen Bambach’s recently published four-volumes study was haunted by one such expert on Amazon. Note: a four volume-study today, in the age of the book reinvented digitally, is a statement in itself. Perhaps it (its physicality) can be interpreted as: the author of these four volumes is not a shadow Leonardo expert (a pdf, distributed for free, would send another message, since pdfs, as far as I know, do not cast any shadow).

ps: is the shadow Leonardo expert male or female? My guess would be that he is male. The Leonardo expert by the way can be male or female, it is not an exclusively male business. And the past has seen noteworthy writing on Leonardo by women (Anna Maria Brizio, Antonina Vallentin, Marie Herzfeld, to name a few women writers and scholars).

2) Leonardo scholarship is not very dedicated to a culture of memory. Is it about secretly exploiting your predecessors while publicly practicing damnatio memmoriae? I would not say so. But I think it has something to do with knowing that even the great pioneers (like Jean Paul Richter) are also to be associated with some dead wrong attributions and guilty for having created some fancyful myths. Note: the Leonardo expert is rather monomaniac. One single person has to cover everything, in one big monograph (four volumes or not), and you don’t have time to read your predecessors (or even contemporaries). Ironically this results (and has resulted over many decades) in a gigantic body of literature that actually no one is reading, not even the specialists who, as everyone seems to assume, should do so. No, it is about me and the sources, me and the pictures, me and the drawings. The wheel has to be reinvented as often as possible. And this, little surprise, leads to an even bigger body of literature. An enormous resource, worth to be studied in itself (as if it were literature and purely ficticious).

3) The Leonardo business requires the Leonardo expert to do infotainment. This is the only reason the public knows at all that Leonardo experts do even exist. It is about being as shallow as possible while at the same time about pretending that everything has to do with studying a genius. This leads us to ask if the nomenclatura of Leonardo experts is to be seen as the real elite of experts at all. Why not becoming a Leonardeschi hermit instead of a Leonardo expert? Many reasons would speak for that: it is about the intellectual challenge (if you are seeking one) and about the intellectual adventure, you get to see all kinds of exotic places (because some Leonardeschi paintings are in some quite exotic places), and most of all, you will discover the best way to study Leonardo. Because the Leonardeschi are the real, if all too silent, eye witnesses. We don’t know Leonardo da Vinci well, since the Leonardeschi are studied too little. This was a truism in the 19th century as it is a truism today.

ps: every serious Leonardo expert must know that people are not very keen to delve into some serious studies of Leonardo. Much too demanding and stressful. It is about admiring a cultural pharos from a distance. And the simple function of the Leonardo expert is to confirm again and again that Leonardo was a genius. If you come with something else, people get bored and turn your back on you.

ps2: so if you are seriously interested in Leonardo: rather try to become a Leonardeschi hermit.

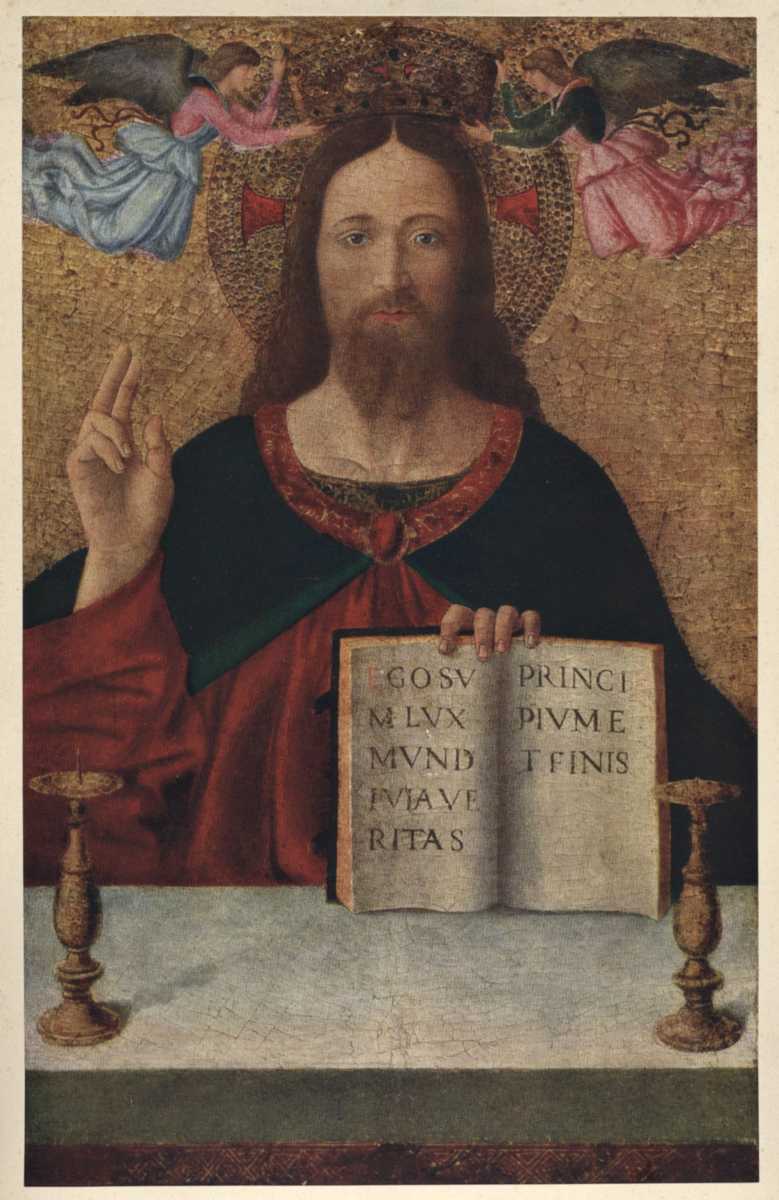

Lux Mundi:

We know of the Melozzo da Forlì Salvator Mundi which is usually presented to us as a reference for a Salvator Mundi picture by Leonardo da Vinci. But there is also an interesting picture of a Christ which has been attributed by Federico Zeri to a follower of Melozzo (picture: fondazionezeri.unibo.it). Perhaps, given this is true, the picture is therefore more or less contemporary regarding our picture in question (the Abu Dhabi Salvator).

What is interesting about this Follower of Melozzo da Forlì Christ is that, while it is formally very similar to a Salvator Mundi (just replace the book with an orb), it names the other attributes of Christ. In a book. Ego sum lux mundi. Via veritas. And: Principium et finis. And all three are interesting (for principium et finis see below).

What interests us here is the light. Christ as the light of the world (John 8,12). And the notorious sfumato. The twilight, the haze, the atmosphere, the chiaroscuro.

The question that interests me is: wouldn’t it have interfered with a c. 1500 understanding of Christ to have depicted him in a sfumato twilight? Since the Abu Dhabi Salvator is often compared with the Louvre St. John, a picture that shows a sudden encounter – with a transmitter between the secular and the holy sphere – in a smoky twilight.

But is there a sfumato in the Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi at all? And would it have made sense iconographically?

In my opinion there is no sfumato. Not of the Mona Lisa type (a hazy athosphere), nor of the St. John type (the mysterious foggy or smoky twilight that has a Dartmoor/The Hound of the Baskervilles quality). Christ, even as represented as a Saviour of the World, is still the light of the world, and to depict him in a mysterious twilight would have, in a c. 1500 understanding, undermined this message.

It is true that a Giampietrino attributed picture shows Christ in a mysterious twilight (with the sign of the trinity), but our picture is a Salvator Mundi picture, its devotional message, its probably consolating function. Yes, Christ is the Saviour of the world, but this is consistently linked with Christ being the light of the world. Various aspects may show in a picture. But in a Christian environment other aspects do not simply disappear if not being represented. Ego sum lux mundi. This, as the essential message of the picture, is equally true for a representation of Christ as a Salvator Mundi. For this light and darkness is essential. Twilight is not. Because this would have transmitted the message that Christ was struggling to light the world. Even if Leonardo would have been a decided heretic (which he was not), he would not have represented Christ in a twilight. It would just not have made any sense.

Principium et Finis:

Christ, if represented as a Salvator Mundi, does not lose his other attributes. Ego sum lux mundi. But also: Ego sum principium et finis. I tend to think that the omega-shape in some Salvator Mundi draperies is either referring to that attribute, or has remained part of the design, because it once was referring to that attribute. We cannot be certain.

On the level of attribution and regarding the Salvator Mundi ›family tree‹ (the relations between the single individuals), this shape has become an interesting clue: the so-called Ganay version (shown in the Louvre exhibition) has it (as in the one Windsor preparatory drawing). The Abu Dhabi Salvator looks as if the author did not care about working this particular shape out that, on some level (if you know the context of the other versions) was still implied by the design the author worked after.

Now my question: Can we call the Ganay version a copy after the Abu Dhabi Salvator? – I don’t think so. You might try to explain the problem away by assuming that Leonardo took his time and changed the design again and again; and while he did that some copyist might have finished their products earlier than the master himself, and that these copies preserve earlier states of the one masterpiece.

But: If Leonardo did change the design in the very beginning and eliminated the omega-shape rather early in the process, a copyist would not have finished it either. And if Leonardo changed it only a bit later in the process, we would find pentimenti under the last, rather carelessly done layer. Hence I believe that we should rather speak, in this particular case, of a version and not of a copy.

Copying produces similarities. But not every similarity is the result of copying.

ps: it is interesting that everyone seems to be keen to look for codes and hidden meanings in Leonardo pictures. But if there might indeed be something of a hidden, albeit rather traditional symbol, it seems to be of hardly any interest.

Pushkin Museum’s Salvator Mundi, The:

We have been showing the Pushkin Museum’s Salvator Mundi on this website (see here) since 2016. And it was also here, pointing to the already known English Royal provenance of this picture, that the question was raised for the very first time, if the identification of the pictures mentioned in English Royal inventories was correct (this was made more explicit in 2017). Since The Art Newspaper, in their November 2018 piece on the matter, did not acknowledge my work at all (and in the following neither The Times nor any other media around the globe) I have to make clear that the ›rediscovery‹ of the Pushkin Museum’s picture in the context of the Salvator Mundi controversy is my (Dietrich Seybold’s) intellectual property. For everyone with eyes to see the Moscow painting is not only much better preserved than the Robert Simon Salvator Mundi, it is also artistically (and regardless of attribution) the much better painting. At least in our virtual museum, we would place the Robert Simon picture in the basement study collection, while the Pushkin Museum’s painting would belong into the regular collection. We trust that the two pictures will argue this out among themselves in the near future.

The Pushkin painting can be interpreted as a visual reflection on firmness vs. insecurity. The blessing gesture more alluded to than executed, the young Christ serious as a child can be serious and socially insecure at the same time. And there is nothing of that sensibility, which makes the Moscow Salvator Mundi a superb painting, in the Robert Simon picture. (Leonardo da Vinci, by the way, even at the time of #Leonardo500, seems to be admired mainly for skillful naturalism and for special effects; but one should not take this too seriously, because this is really not what art is all about.)

Sfumato assai (abrasion, integration):

See above under Lux Mundi.

ps: Dianne Modestini only recently has conceded that there may be more of old repainting in the face than she initially had thought. Areas of old repaint that for example and especially concern the nose area. For a philological proof (philology of the eye) that I proposed prior to her revelation and that shows that – as a minimum concession – we have to rule out that the nose is original, see my Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts (use link below).

See also: A Salvator Mundi Provenance

Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

Some Salvator Mundi Afterthoughts

Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

Leonardeschi Gold Rush

A Salvator Mundi Geography

A Salvator Mundi Atlas

Index of Leonardiana

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM Some Salvator Mundi Variations  |

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS