M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie  |

See also the episodes 1 to 8 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

And:

The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

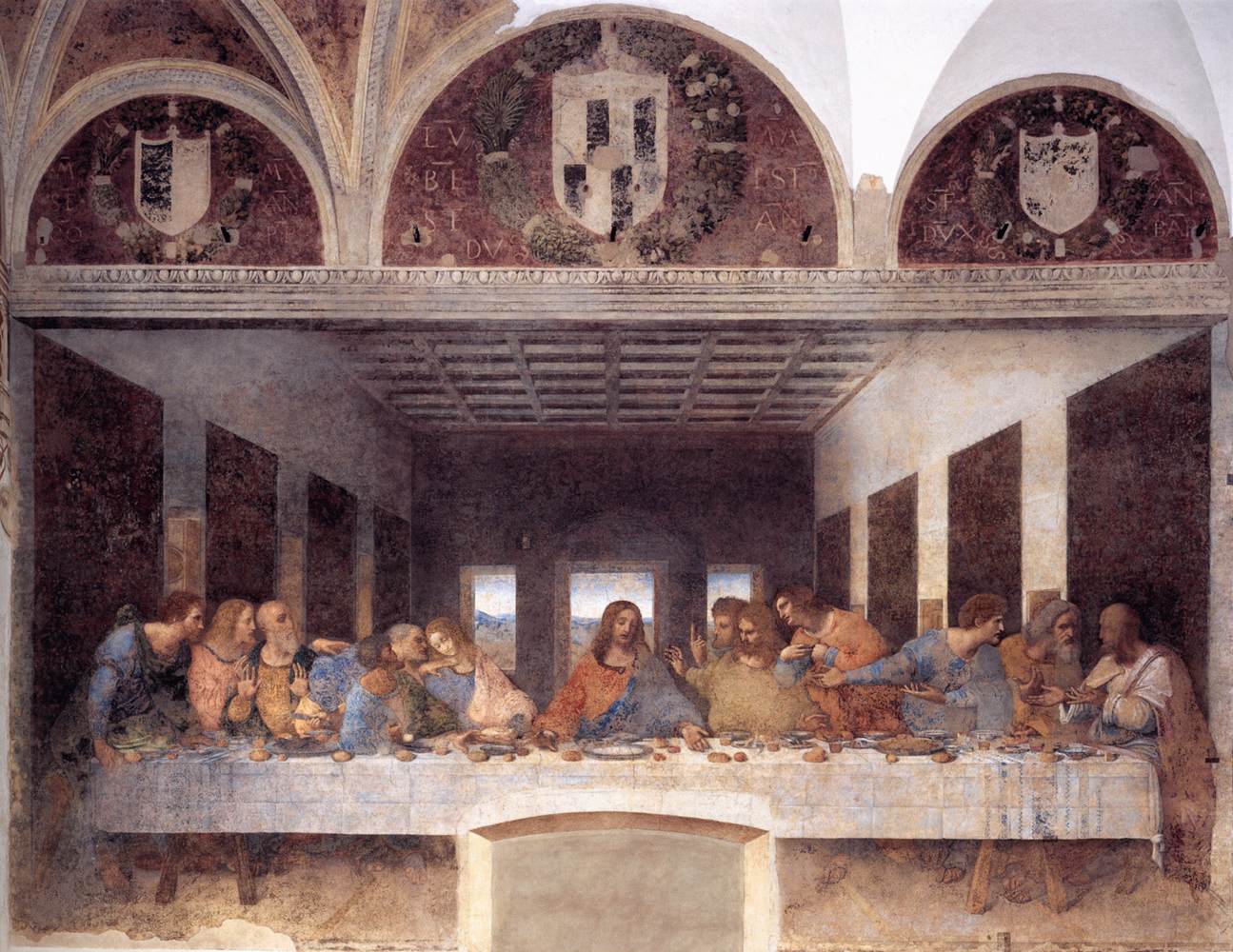

(21.7.2021) Few Leonardo scholars have taken them seriously – but now they’re coming back: the chronicles of Santa

Maria delle Grazie, Milan. We have two of them, an earlier and a later one, and both speak of Leonardo da Vinci having

created – apart from having created The Last Supper for Santa Maria delle Grazie – additional paintings for the

cloister. With the earlier chronicle (by Padre Girolamo Gattico) speaking of a Madonna and a Pietà and the later one

(by Padre Vincenzo Monti) of a Saviour.

And there is a picture in the Hermitage, it is not even on display, but it is the picture of a blessing Christ, it shows

the basic compositional scheme of the Salvator Mundi by Leonardo (with the familiar frontal design, the blessing hand,

the curly hair and the crossed stole – but minus the orb); it is by another artist, but it bears an inscription with a

date: the year of 1495 – which is the date Leonardo is supposed to have begun The Last Supper. And the Blessing Christ of

the Hermitage shows another peculiarity: it shows the thumb of the blessing hand in the upright position, just as it

appears in the pentimento found in the notorious Salvator Mundi version Cook. What do we make of all this? Here comes

the ninth episode of our New Salvator Mundi History (pictures above: Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1743: Marc’Antonio Dal Re;

Hermitage Museum; thumbs: youtube.com / Peoria Riverfront Museum; Viewing Room Live).

One) Prologue

How often have we heard someone explain with a meaningful voice: ›Well, you know, they found a pentimento; and you would

rather not find a pentimento in a copy. A copyist would just copy what is on the surface. But a pentimento is a change of

mind of the artist, and this means: it is rather the original.‹

Yes, but to suggest that there are only originals and copies would be overly simplified art historical thinking, inviting

fusions of overly simplified art historical thinking with marketing interests. Because if a cartoon plus (more detailed)

prepatory sketches) exist for a painting, all the ingredients for serial production did exist for this particular

painting. And we do know that a cartoon for the Salvator Mundi did exist (because traces of spolvero have been found,

traces of a particular tracing technique using powder that is applied to trace a cartoon), and two sheets with

preparatory sketches are among the Leonardo sheets at Windsor. If we find a pentimento in a painting for which all the

ingredients existed that made serial production possible, it is not necessarily a clue for this painting being the unique

original by the supposed artist. It could also be – and how to rule it out? – that the supposed ›change of mind‹ of the

artist is nothing but a switch from option 1 to option 2 as regards the blessing hand, something that can be done in

minutes, and is not necessarily the result of a genius artist carefully reflecting (›fiddling around‹) for decades, until

a final solution was found.

Let’s take a look at what we got here: above we see the upright thumb of the blessing hand in the Hermitage picture

(above on the right). I call the hand with the upright thumb ›option 1‹. In the center we see the pentimento, the change

of mind of the author of the Salvator Mundi version Cook. We also see option 1 (the something that had to be corrected,

the something against which the artist did decide), and we see, in the same picture, the corrected version of the thumb,

which I call ›option 2‹, also being called ›the final position of the thumb‹.

On the far left we see the thumb as newly painted by the restorer (but the question if this thumb is a misunderstood

version of option 2 does not concern us here).

Does the magic of the pentimento evaporate here? Is it nothing but a switch from option 1 to option 2 (for which a

genius artist is not even necessary)? Is it all just the result of serial production? Is the Salvator Mundi version Cook

indeed not the unique original, but just a workshop version that preserves a switch from option 1 to option 2?

We should not throw out the baby with the bath water (as the German idiom has it), and I will draw my conclusions below.

But first we have to think more carefully about the Hermitage picture, about the questions it raises, and about its

possible author. But what should be said right now is that the probability that option 1 and option 2 did exist long

before the Salvator Mundi version Cook was painted is fairly high. It might have elapsed Leonardo scholars, but the Ganay

version of the Salvator Mundi has, according to Sotheby’s, been attributed to the young Giampietrino by Cristina Geddo,

the only active Giampietrino scholar there is. And Giampietrino is documented from around the year 1495. If Geddo is

right, option 2 did exist long before version Cook was painted, since all the standard narrative give a rather late date

for version Cook (and as shown option 1 does exist in the Hermitage picture). But also even if Geddo would not be right,

we have a cluster of other Salvator Mundi pictures, all undated pictures showing option 2, that all could be earlier

than version Cook. And last but not least: the Hermitage picture is not the only picture showing option 1. The Young

Christ at Bergamo (below), once owned by Giovanni Morelli, has it. This picture is also undated, but also this picture

could be earlier than version Cook. Brief: the chance that the magic of the pentimento is about to evaporate is fairly

high – and the Hermitage find forces to rethink all the basic assumptions of Salvator Mundi authenticating: if you want

to make the world believe that there is a unique autograph original, you have to rule out the possibility that there was

serial production. But what in fact was the case was that, negligently, a unique autograph was postulated before actual

serious research on all the other versions had been done. Now the ›truths‹ of then, it seems, have to be revised, due to

a crucial new find, because the possibiliy of serial production had never been seriously considered (below the Young

Christ once owned by Morelli, along with the adult Christ, also from Morelli’s collection, and just one example of a

picture that shows the final position of the thumb, and could be earlier than version Cook).

Two) Three Possibilities

The Hermitage pictures offers us three possibilities to work with, and I am going to explore each one of them:

1) The date of 1495 in the inscription is correct

If the date is correct (and not due to error, for example, of the heirs of a painter), then it is likely that this

picture – whose relation to Leonardo’s work is obvious, while it is not a work by Leonardo – preserves something

that could be seen at Santa Maria delle Grazie, because this is where Leonardo was busy then, and because one later

chronicle of Santa Maria delle Grazie does transmit that Leonardo indeed did realize the picture of the Saviour there,

in addition to the Saviour in The Last Supper; the Monti chronicle (unedited as it is, because Leonardo scholars do

not seem to care about it) seems to mention a Saviour, and not a Salvator Mundi, which is crucial, since the orb in

fact is lacking in the Hermitage picture, the orb, which would make the picture be a Salvator Mundi; we might think

of the possibility that Leonardo had prepared alternatives for the lunettes of the cloister, and that a Pietà was

realized (which is confirmed by an note by Leonardo in the Codices Forster, by the way; see Leonardo biography by Charles

Nicholl, German edition, p. 377), while that the Saviour existed only as a cartoon; either a painting existed that the

artist of the Hermitage picture might have copied or paraphrased, or a cartoon; but one might measure the quality of

copying/paraphrasing by measuring the resemblance of the blessing hands; in either way it is likely that the artist was

granted permission by Leonardo to copy and to work close to him, and that a relation of some kind between these two

artists must have existed;

2) The date of 1495 is not correct, but the Hermitage is vaguely right in assigning the picture to a

16th century artist

If the picture cannot be linked to Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1495, it still does show the thumb of the blessing hand

in its upright position, and one would face the possibility of two parallel traditions of the Salvator Mundi design,

one with option 1 (as also in the Young Christ, owned by Morelli) and one with option 2; it would depend on the dating

of these pictures to verify if version Cook is earlier than the Hermitage picture and the Morelli Young Christ or

not; but the Hermitage picture cannot be a copy of version Cook, since it does show option 1 of the hand, which in

version Cook is underneath the surface; it only could be a copy, if such copy was done in parallel to version Cook;

if it was not, we would have a picture showing option 1, indirectly raising the question if also option 2 of the thumb

did exist before version Cook was realized (going back to option 1, but deciding against it by proceeding to option 2,

and this all resulting with the pentimento);

3) The Hermitage picture was done in parallel to the Salvator Mundi version Cook

This possibility, as unlikely as it is, would make the Hermitage picture a find comparable to the Prado Mona Lisa:

another artist must have been so close to Leonardo da Vinci, that this particular artist could work in parallel, at least

for some time, since the artist of the Hermitage picture must have finished his picture before the artist doing version

Cook, supposedly Leonardo, decided against option 1 of the thumb; it is noteworthy also that the size of the two pictures

is comparable (the Hermitage picture differs only few centimetres from version Cook);

since the blessing hand preserves much of what we see also in the blessing hand of version Cook, the question would be

raised, if also the rest of the Hermitage picture preserves something of the state of the version Cook at the time it was

copied (especially as to the face of Christ);

all other questions as to options 1 and 2 as possibly existing before version Cook was produced, however, do remain as

long as all other versions would be precisely dated (if for example version Ganay is indeed by young Giampietrino, option 2

must have existed before version Cook was created, and perhaps also option 1, since it shows in the Young Christ,

once owned by Morelli.

Three) A Hypothesis as to Authorship

As a first working hypothesis I would like to propose that the Hermitage picture might have been painted by

Paolo da San Leocadio, and that the inscription thus would read as ›Leocadio Santo, anno 1495‹ (respectively ›año 1495‹

as an alternative). The Hermitage thinks of an unknown Spanish artist as being the author of the picture.

Paolo da San Leocadio was an Italian, born in Reggio Emilia in 1447, who settled in Spain. Scholars of University of Valencia

have done good work to compile what we know about him, although our knowledge does remain very fragmentary.

The name of the artist might be derived from Saint Leocadia in some way (since a male saint of the name Leocadio does

not exist), and we know that Paolo, although he settled in Spain, also spent several years in Italy, even after settling

in Spain. Roughly ten years before a supposed encounter with Leonardo da Vinci in Santa Maria delle Grazie Paolo produced

a picture of Christ (now in the Prado) that reflects an interest in the Van Eyck Salvator type (picture above: useum.org);

the Hermitage picture, if the inscription gives the date correctly, would reflect the encounter with Leonardo; and a

Christ with Host (in Poznan) can be dated, if vaguely, also in the 1490s. Paolo de San Leocadio seems to have worked for

the Borgia, and apart from being an interesting link between the Borgia and Leonardo, it is very likely that, as an

Italian working in Valencia and travelling also back to his home country, he might have been a crucial intermediary

between the two Spanish Leonardeschi Fernando Yáñez and Hernando de los Llanos, who were both active in

Valencia as well.

Four) Conclusions

The authentication of the Salvator Mundi version Cook had not been based on the interpretation of the pentimento alone.

But it had been based on the magic of this pentimento, in combination with the argument of quality. The quality of the

best preserved parts of the picture – and the pentimento, these are the main pillars the attribution had been based on

(with additional references to a very questionable tradition, initiated by Wenzel Hollar, and with additional references

to documentary evidence in collections, and of course with references to the Windsor sheets). And as I have said above –

we should not throw out the baby with the bath water. The blessing hand in version Cook is, in my view as in the view of

many viewers, of a very high quality. Even if I think that the hand of St. Michael in the Vierge aux balances in the

Louvre should be compared with it, it seems to me that the blessing hand is worthy of Leonardo and I have interpreted it

as one of his last words as a painter here in my New Salvator Mundi History.

Because this was and still is my interpretation of the case: Leonardo did retouch what his pupil Francesco Melzi had

prepared for him to refine, in 1516 to 1519.

I have always thought that the design of the picture can be traced back to Santa Maria delle Grazie where Leonardo da

Vinci, according to the chronicles of the cloister, did additional works. And the frontal design of the Saviour is

comparable anyway to all the marginal Christs and Saints that are to be found in the margins of more complex designs,

in churches and chapels, but not necessarily, as marginal designs, are in the focus of art historians. Just like the

lunettes in Santa Maria delle Grazie has never been really in the focus of Leonardo scholarship.

In 1495 Francesco Melzi was perhaps three years old, and if, as I am thinking and as I have argued, he prepared a

Salvator Mundi painting for Leonardo to refine, many, many years later, he might not have been aware that there was

option 1 and option 2. Leonardo might have seen what Melzi had prepared for him – the basic layer, prepared in the

middle tone of skin colour – and Leonardo might have decided against option 1 with its upright thumb, being also reminded

of the history this hand design may have had, being reminded of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The modelling of the hand,

it should be said once, was the fun part (especially if compared with producing of the more complicated ornamental work),

only two additional tones necessary, a lighter tone for the lighter parts, and a darker tone (perhaps with a touch of

additional blue, resulting in some greyish skin tone) for the shadows. Such modelling on a chromatic scale does require

much more knowledge than it does require fine mechanics of the hand that executes it. One has to know what one is doing

and what one wants to achieve. If one does know, such modelling after a pre-existing design can even be done very

fast.

Melzi might have handed over the palette to his mentor, and the old Leonardo might have retouched the painting. What we

see is a product that must come out of the workshop, either that of Leonardo or that of Melzi, his heir, just because

the two options show in version Cook – it is workshop routine and repertoire that shows here, not tradecraft.

But the mere fact that these two options do show here does not make the picture a fully autograph unique masterwork by

Leonardo da Vinci. Although the idea was certainly his (not an earthshaking one, since virtually all ingredients of the

design already existed, as did the iconographic idea of Christ holding an orb as Charlemagne is holding an orb), and

although he probably did retouch the picture, since for the ultra-refined parts of the picture I see no other candidate.

Not at Amboise, and not elsewhere.

Apart from the new light that is shed on Salvator Mundi thinking by my Hermitage find, we should not undervaluate that

this find does offer a whole number of fresh perspectives: Paolo da San Leocadio as the intermediary between Leonardo and

the Spanish Leonardeschi (and possibly between Leonardo and the Borgia); a whole new and fresh perspective on Leonardo

working in Santa Maria delle Grazie (and on its chronicles). But last but not least: this find sheds new light on some of

Leonardo’s notes in the Codices Forster. And if I have mentioned above the one that refers to a Pietà (Leonardo actually

mentions that the ›head of Cristofano from Castiglione lives in the Pietà‹, which can be read as Leonardo saying that the

head of the model lives on in the picture of a mourned Christ, i.e. Christ being dead), one should now mention the note

that refers to the hand of Christ. The Christ in The Last Supper has two hands, but Leonardo is speaking here of one

hand, and this could be the notoriously, but deservedly famous blessing hand in the Salvator Mundi design. If it is, we

would see the hand of Alessandro, perhaps one of the monks. Alessandro was from Parma. He had been, as Leonardo says,

the model for the hand of Christ (see again Nicholl, p. 377; the picture below shows the high quality copy of The

Last Supper in the Royal Academy of London).

Selected literature:

Fra Girolamo Gattico, Descrizione succinta…, ed. Elisabetta Erminia Bellagente, Milano 2004

(See p. 104, line 36ff.: »Dipinse anco quella meza luna, qual è sopra la porta maggiore della chiesa, l’imagine

santissima miraculosa della Beata Vergine, un Cristo in forma di pietà, qual era sopra l’antica porta che entrava dalla

chiesa al claustro a lei vicino, che poi, aggrandendola, fu inavadutamente demolito sino l’anno 1603, non avertendo fosse

così insigne pittura.«

Francesco Malaguzzi Valeri, La corte di Lodovico il Moro, vol. 2 (Bramante e Leonardo da Vinci), Milan 1915

(see p. 558)

1495: At around this date Leonardo da Vinci is supposed to have begun The Last Supper. Giampietrino is documented as an active painter.

1516: Paolo Emilio, Italian-born humanist at the court of Francis I, publishes the first four books of his history of the Franks; death of Boltraffio.

1517: Leonardo da Vinci, with Boltraffio and Salaì, has come to France (picture of Clos Lucé: Manfred Heyde); 10.10.2017: Antonio de Beatis at Clos Lucé

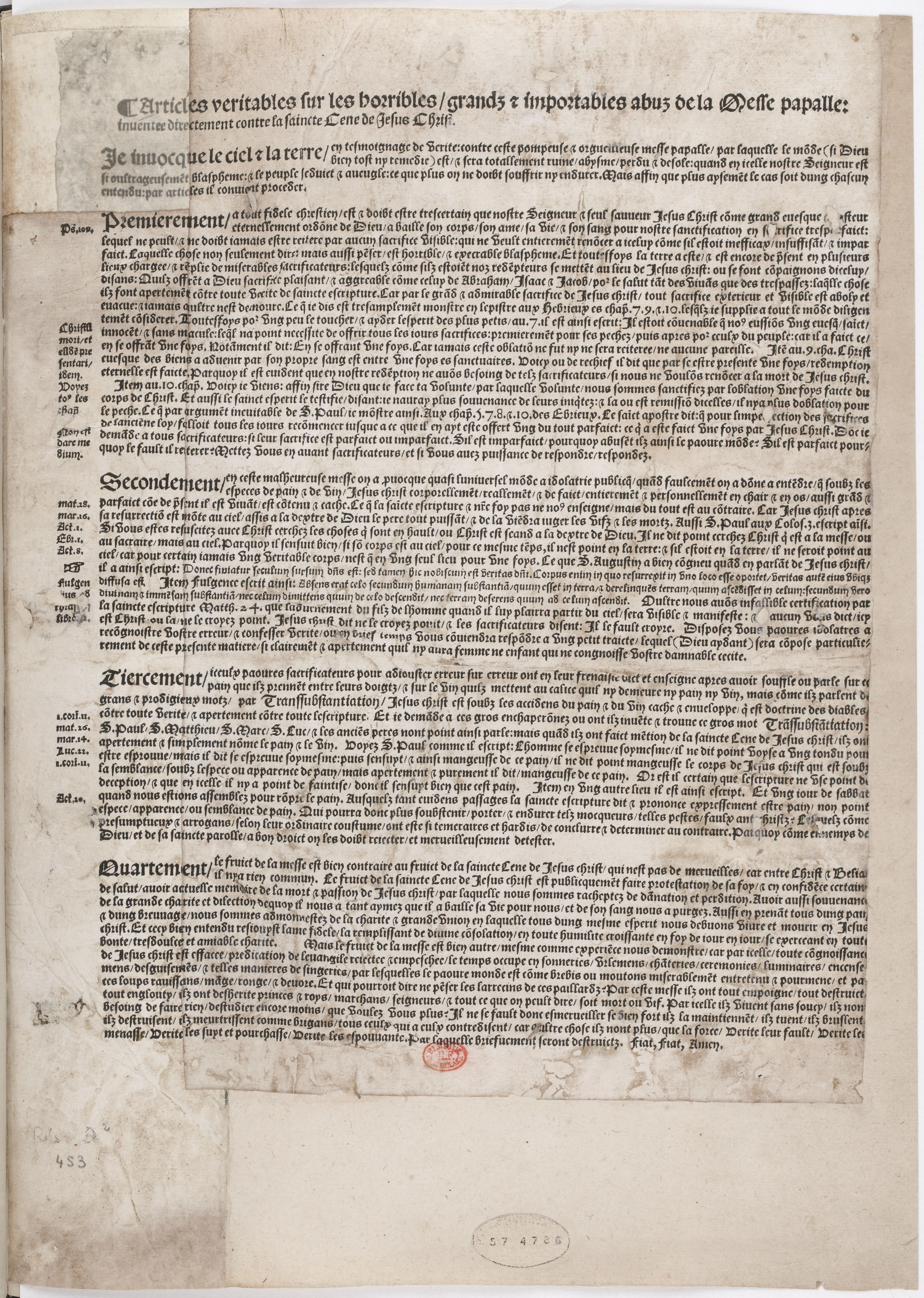

1517ff: Age of the Reformation; apocalyptic moods; Marguerite of Navarre, sister of Francis I, will be sympathizing with the reform movement; her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, mother of future king Henry IV, is going to become a Calvinist leader.

1518: the Raphael workshop produces/chooses paintings to be sent to France; 28.2.: the Dauphin is born; 13.6.: a Milanese document refers to Salaì and the French king Francis I, having been in touch as to a transaction involving very expensive paintings: one does assume that prior to this date Francis I had acquired originals by Leonardo da Vinci; 19.6.: to thank his royal hosts Leonardo organizes a festivity at Clos Lucé.

1519: death of emperor Maximilian I; Paolo Emilio publishes two further books of his history of the Franks; death of Leonardo da Vinci; Francis I is striving for the imperial crown, but in vain; Louise of Savoy comments upon the election of Charles, duke of Burgundy, who thus is becoming emperor Charles V (painting by Rubens).

1521: Francis I, who will be at war with Hapsburg 1526-29, 1536-38 and 1542-44, is virtually bancrupt.

1523: death of Cesare da Sesto.

1524: 19.1.: death of Salaì after a brawl with French soldiers at Milan.

1525: 23./24.2.: desaster of Francis I at Pavia. 21.4.1525: date of a post-mortem inventory of Salaì’s belongings.

1528: Marguerite of Navarre gives birth to Jeanne d’Albret (1528-1572) who, in 1553, will give birth to Henry, future French king Henry IV.

1530: Francis I marries a sister of emperor Charles V.

1531: death of Louise of Savoy; the plague at Fontainebleau.

1534: Affair of the Placards.

1539: the still unfinished chateau of Chambord is being shown by Francis I to Charles V.

1540s: the picture collection of Francis I being arranged at Fontainebleau.

1544: January: Marguerite of Navarre sends a letter of appreciation to her brother, king Francis I., who has sent her a crucifix, accompanied by a ballade, as a new year’s gift.

1547: death of Francis I.

1549: death of Marguerite de Navarre; death of Giampietrino.

1553: Jeanne d’Albret gives birth to Henry, the future French king Henry IV and first Bourbon king after the rule of the House of Valois.

1559: publication of the Heptaméron by Marguerite de Navarre.

1562-1598: French Wars of Religion.

1570: death of Francesco Melzi.

1589: Henry, grandson of Marguerite de Navarre and grand-grandson of Louise of Savoy, but by paternal descent a Bourbon, is becoming French king as Henry IV.

2015: an exhibition at the Château of Loches is dedicated to the 1539 meeting of king and emperor (see here).

The 15 November 2017 inscribes into the chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie as well (pictures: youtube.com / Christie’s). Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers as well as the Salvator Mundi have their roots in the Milanese cloister. And there is something else: While the Salvator Mundi might mark the beginnings of serial production of paintings at the time of the Renaissance, Warhols work does practice and selfreferentially comment on serial production and on viral images (it had been a commission by an art dealer; see here). Does it also comment on the Salvator Mundi? How would Warhol have commented on the Salvator Mundi saga? Would he have created Sixty One Plus Salvator Mundi Versions? Perhaps he might have thought or said: why underestimating Leonardo? he did in fact invent the multiple. And perhaps Leonardo was even more furbo than anyone ever imagined – perhaps Leonardo did also invent and practice the selling of serial productions as (more or less unique) originals, each of every member of a series. Do we have a category for such objects, or do we still have to find one (even if just the Salvator Mundi version Cook might have been a gift and not a commercial product)?

See also the episodes 1 to 8 of our New Salvator Mundi History:

Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

And:

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS