M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Encounter of Harry S. Truman with Pablo Ruiz Picasso

(26.1.2023) ›Ruiz‹ was Pablo Picasso’s actual family name (the name of his father). He began to sign as ›Picasso‹ (the name of his mother) in 1901. Before that he had signed with ›P. Ruiz‹, ›P. Ruiz Picasso‹ (or ›P.R.P‹) and also with ›P.R. Picasso‹ (see Fox II, 1102). If I have added the name of Ruiz here in the title of this discussion of Picasso’s meeting with former US-president Harry S. Truman in the late spring of 1958, with Truman being on his second post-presidential European trip, it is to indicate from the beginning that this was a meeting full of tensions. Subliminal tensions perhaps, but graspable subliminal tensions. Not only because these two men represented opposite sides in the arena of the Cold War – with Pablo Picasso being a member of the French Communist Party – but also because these two men represented Modernism in Art (with Picasso being the embodiment of Modernism) versus a distaste for Modern Art (and, by the way, for any Art with a capital A), a distaste which was, needless to say, represented by Harry S. Truman (with the capital S in the name, by the way, being an initial derived from the names of his grandfathers, and not indicating a second first name).

If this encounter has never been discussed in detail up to the present day, it is because an actual political biography of Pablo Picasso is lacking. What we have, in 2023, are fragments. But from fragments, one day, an actual political biography of Picasso, or a biography that at least will encompass the political Picasso in full, will be written. And I am adding here a fragment that is worth to be studied in detail, because there is much to learn from it.

(Picture: DS; Google search)

(Picture: DS; Google search)

(Picture: trumanlibrary.gov; at Vallauris)

Let’s embark on that journey to meet Picasso (with Harry S. Truman). And we have to take the S.S. Independence, leaving New York on May 26, 1958, with destination of Naples (Ferrell (ed.) 1980, 359). And while we are crossing the Atlantic we may prepare a little bit for our meeting with Picasso (on June 11). But Harry S. Truman did not sail the Atlantic primarily to meet Picasso. Actually his diaries seem not to mention the encounter at all, because otherwise, his biographer Robert H. Ferrell would certainly have included excerpts into his biography or his edition of sources. But Ferrell actually mentions the encounter only briefly and places it in the context of Truman’s (more official) 1956 trip to Europe (Ferrell 1994, 398), which is false. The meeting took place, as the Truman Library has established by dating photographs, on June 11, 1958. Which corrects also the one source reflecting Picasso’s side of that encounter, which are the memoirs of French journalist Georges Tabaraud, to whom Picasso spoke about that encounter (actually Picasso invited Tabaraud, a fellow member of the French Communist Party, especially to talk about the event, not without telling him to keep everything to himself). It was only in 2002 that Tabaraud, not without especially mentioning that the story he heard was the way Picasso told him about the event, made Picasso’s view known, while, at his lifetime Picasso had also spoken about the encounter at least to Roberto Otero (compare Utley 2000, 113). Tabaraud placed the event in 1957, which might be a slip of memory.

Cultural Coordinates

A diary entry of 1953 gives us a quite concise profile of the cultural tastes of Harry S. Truman. This entry might be quoted here in full (Ferrell (ed.) 1980, 299), because this is necessary to set the scene, and otherwise we would know too little as to the cultural preferences of the former US-president:

»Been reading an article in the New Republic on Art with a capital A. It is a review of a book by André Malraux called Voices of Silence. After reading it I felt as if I’d read a third level State Department monograph on the Cold War. But the reviewer wound up with an understandable sentence, he advised the reader to buy the book for $25.00. Most modern readers dislike to pay 25 cents for a Western or a Murder Mystery. Can you imagine any one of them paying $25.00 for a book on »Art«?

Well the vast majority of readers will not pay $25.00 for any book, let alone one of capital A Art.

I am very much interested in beautiful things, beautiful buildings, lovely pictures, music – real music, not noise.

The Parthenon, Taj Mahal, St Paul’s Cathedral in London, York Minster, Chartres Cathedral, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the Capitol buildings of Mississippi, West Virginia, Utah, Missouri, the New York Life Building, N.Y. City, the Sun Insurance building, Montreal, the Parliament Building in London, the Madeleine in Paris, the lovely Palace of Versailles, St Mark’s and the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Pictures, Mona Lisa, the Merchant, the Laughing Cavalier, Turner’s landscapes, Remington’s Westerns and dozens of others like them. I dislike Picasso, and all the moderns – they are lousy. Any kid can take an egg and a piece of ham and make more understandable pictures.

Music, Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Mendelssohn, Strauss Waltzes, Chopin waltzes, Polonaises, Etudes, Von Weber, Rondo Brilliante, Polacca Brilliante. Beautiful harmonies that make you love them. They are not noise. It is music.«

In the South of France, and here Truman might have found common ground with Picasso, he showed interest in antiquity: »have been investigating Roman ruins in Nimes, Avignon and Arles«, as it says in a letter by Truman (after already having met Picasso), in a letter dated by June 21 (Ferrell (ed.) 1980, 361). And in a letter probably written while just leaving for France, he stated (ibid., 360):

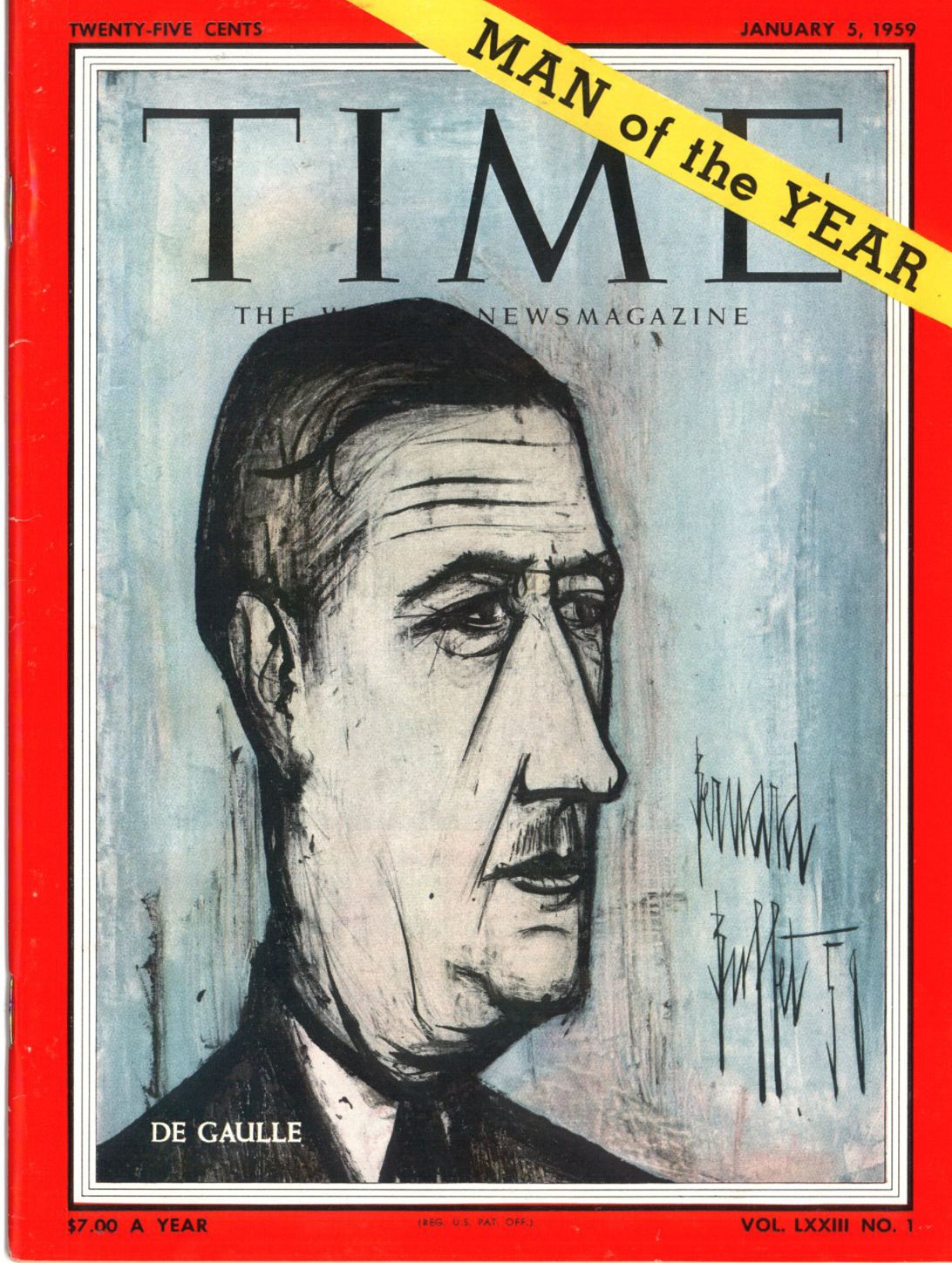

Another reason for anger: not only a portrait of Charles de Gaulle,

but also a portrait by then much hyped artist Bernard Buffet

»In this South of France there are many places worth seeing for their historical background. There are also some beautiful views if you can get yourself to forget the vandalism of the ignorant Christian Middle Ages before the Renaissance. Some of the most beautiful monuments of antiquity were used as quarries and some were willfully destroyed for propaganda purposes.

Athens, Rome, Alexandria, the great cities of the Nile and the Near East along with the historical cities of this southern France are only a few examples. My interest has been to see what a great civilization of the past could do and had done. It makes me wonder what may happen to our so-called modem set-up.«

The Trumans, Harry and Bess, who did not speak French fluently, did, by the way, this trip with the Rosenmans who did speak French fluently. Sam Rosenman had written speeches for US-president Franklin D. Roosevelt as well as for Harry S. Truman.

The Political World of 1958 and the Private World of Pablo Picasso

The year 1958 was the year photographer David Douglas Duncan published his very successful Private World of Pablo Picasso book (Duncan 1958), establishing the image of a ›buffoonish‹ Picasso, of ›buffoonish‹ years. Most of the images were made in 1957, however. The year of 1956 is much less highlighted, and when Picasso and Truman met, in June of 1958, the mood was certainly not only buffoonish, but had just dramatically changed. Charles de Gaulle had, to the anger of Picasso, just been summoned back after a coup of French officers in Algeria. And from May 25 to June 9 Picasso had painted a Nature morte à la tête de taureau (see D 617), which is usually associated with his anger of seeing de Gaulle returning to power. The French Communist Party as well as Picasso did not expect something good to come from that (for the general atmosphere see Brogi 2011).

In addition to that it has to be said that Picasso probably had also enough seen of Picasso-tourism, stealing his time. And certainly he did not like just to be seen as a kind of trophy, so that a visitor, who might have been interested in fame and myth, but not even in Picasso’s art, might have been able to write into a diary: just visited Picasso (in the next year, in 1959, he was, for various reasons, to leave villa La Californie, for some time, moving to Vauvenargues).

He had welcomed visitors, also spontaneously. In 1955 for example he had welcomed the late Fred Baldwin, who was to become a photographer after that visit, in the summer of 1955, and provided us, due to his short but – for him – decisive 1955 visit, with valuable photography of the interior of villa La California at a time Picasso had just moved in; before, that is, the house was full of works and arts as well as other objects (like a cabinet of wonder), as it can be seen in many of Duncan’s famous photographs, but still rather empty. Picasso had also welcomed actor Gary Cooper, and his stance on the United States was not generally negative, although also some anti-American resentments seem to be on record. But Harry S. Truman certainly embodied everything Picasso disliked, although the Picasso of 1958 was in no way still a Stalinist communist. But during the ›Stalinist years‹, especially during the years of the Korean War, US foreign policy – the US fleet could be seen also from Cannes – certainly represented what the political Picasso, encouraged by even more determined political friends, disliked and disdained. He still had hopes as to the Soviet leadership, while Truman had referred to Khrushchev and consorts as ›tools of Stalin‹.

On Shirts and Suspenders

French journalist Georges Tabaraud introduces his account of the meeting of Truman and Picasso (in Tabaraud 2002, 203ff.) with a discussion of Picasso’s – at times cruel – humour (some said: just, not cruel). We have to stay aware, and Tabaraud does give us all reasons to stay aware that what we have is the paraphrasing of an eye witness account (by Tabaraud; the account given by Picasso, probably early in 1959), an account that might be accurate or not as far as Tabaraud is concerned, but what the journalist had learned had been already filtered by Picasso, framed by Picasso, inspired perhaps also by all the notorious storytellers, raconteurs, around Picasso (of which the greatest was known to be, if he was in a good shape, Jean Cocteau).

And actually there were two storytellers, because Picasso, in telling the story, was assisted by Jacqueline Roque, who had been present at the events (see also the photograph below), and who, fluent in English, had supported the translator who had been probably mainly Sam Rosenman, but a Rosenman who seems to occasionally have given up the task of interpreting, given the mood, offering to Jacqueline the chance to take the initiative.

Tabaraud is, as a chronicler, not always reliable: his background informations refer to Truman just having given up his office, not to the Truman on his second more private post-presidential European journey in 1958. But it seems likely that the US-ambassy had been involved for preparing this visit, and, rather unwillingly – and after realizing that it was not a joke –, Picasso seems to have accepted to being visited just as a sight (with/in his studio). One had apparently explained to Picasso that it was customary that an ex-president of the United States got a present from the state, and that this tour, this opportunity to see Picasso, was such present. But here fact and fiction may already be mixed. Be it as it may: Picasso, respectively his studio, had been on somebody’s list of sights.

Is it true that Picasso held Truman responsible for McCarthyism? Tabaraud says so, and it could be true, since Picasso’s political views were not always, although he had access to many, many channels of information, very nuanced.

According to Tabaraud Picasso seems to have thought about refusing, saying that he was busy working on a large canvas (and it would be interesting to know if Picasso thought of the canvas into which, apparently, his anger about Charles de Gaulle’s return to power was worked into, and if this had been a good excuse, since Truman and de Gaulle had not had an easy understanding, years ago, in the first postwar years, that is, with Truman apparently having advised de Gaulle to cut communist influence in his government).

The actual visit seems to have followed a scheme of brief introduction (buffoonish or not, and the buffoonish Picasso is actually also the shy Picasso who used buffoonish performances, if there was no other bond between him and his visitors), after which Picasso would immediately have proposed to show his pictures. Which he seems to have done also in this case, but not with the result obviously, to trigger an interest in Truman for his art. And Truman, as Picasso said to Tabaraud, »commençait à m’énerver«. And Tabaraud imagined that Truman might have written in his diary in the evening: ›seen Picasso in his studio‹.

After that, it seems (but Tabaraud does not seem to be completely sure), that one left the studio to do a tour to Vallauris to see the chapel with Picasso’s The War and The Peace. Picasso and Truman seem to have arrived at Vallauris, because one photo (the one above) must be Vallauris, but it seems not completely sure that the two men (or the three couples) looked at the work by Picasso together that had been inspired by the Korean War and included a reference to the idea/claim/suspicion that the United States’ forces had used bacteriological weapons during that war (for more informations on this element of communist propaganda see here; and see again Brogi 2011).

One has to say here that Picasso had, during these years 1950-53, even been asked to do posters against the use of bacteriological weapons (see Utley 2000, 166 and 239, note 91), posters, however, that Picasso never did.

Tabaraud now goes on to give details that seem to ascertain that a visit of The War and The Peace had taken place. One had spoken of Goya, of the horrors of war, of the money spent in war etc. and here Jacqueline seems also to have supported and completed the translation, asked by Picasso, and by saying that at the origin of this work the Korean War had been. And one did return to the villa to say goodbye.

It may be that here again truth and fiction are mixed, because it seems that the three couples rather – or also – visited the Picasso Museum at Antibes. And perhaps there is some confusion here.

At the villa, then, Truman again could marvel at the thousands of objects in the artist’s studio, while Picasso apparently was looking for a goodbye-gift, as often visitors were leaving with a drawing or a print. And now Truman seems to have warmed up at seeing some multicolored shirts that actually had been a gift to Picasso from Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, and now the scene was turning into ›buffoonish Picasso‹, who seems to have suggested to Truman, who had asked if these multicolored shirts were his creations, that yes, to the effect that now Jacqueline was looking at Picasso as if he had gone crazy, but now a lively discussion was ensuing on these shirts, with Picasso now in the role of an artist producing shirts (Truman had been, early in his career, a co-owner of a store for men’s wear), but not only shirts but also robes, and even suspenders.

At this point, apparently, only Jacqueline was still willing to translate. And Truman now began to speak of his experiences in men’s wear, and the possible synergies between art and fashion. Which resulted that Picasso and Truman now discussed a possible cooperation in that field. But it seems that for the other visitors the visit had come to an end, and one did say goodbye with the usual niceties and invitations (to further discuss the project of shirts and suspenders). Which led to the final point, the only actual fragment that seems to be known to Picasso literature, which is the fragment of Picasso recalling that the US, respectively Truman had not allowed Picasso a visa to enter the US, years ago, when the artist had wanted to attend a conference of the Peace Movement.

(Picture: SchiDD)

(Picture: SchiDD; sculpture by Germaine Richier)

(Picture: trumanlibrary.gov; this is the scenery of Antibes (not Vallauris, as trumanlibrary.gov has it);

it is the terrace of the Picasso Museum at Antibes in the Château Grimaldi; the ›unidentified woman‹ (second from left) is Jacqueline Roque, whom Picasso married in 1961)

A Postlude

»Return was on the Constitution, leaving Cannes on July 1, arriving in New York on July 9« (Ferrell (ed.) 1980, 359), but also a postlude has to be mentioned, because this postlude explains in what context Harry S. Truman, after having met Picasso, had referred to him as a ›French Communist caricaturist‹.

The necessary informations we find in Ferrell’s Truman biography of 1994 (398 and note on p. 450f.): »[…] he received a letter from an inquirer at Roosevelt University in Chicago, asking about the availability of Picasso to accept a commission from the university. The answer [dated June 15, 1958] was snappy: »It seems to me that a University named Roosevelt would try to obtain one of our able American painters for your purpose rather than a French Communist caricaturist.««

Further Reading:

Robert H. Ferrell (ed.), Off the Record. The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman, New York etc. 1980;

Robert H. Ferrell, Harry S. Truman. A Life, Columbia/London 1994;

Georges Tabaraud, Mes années Picasso, Paris 2002;

Gertje R. Utley, Picasso. The Communist Years, New Haven/London 2000;

Alessandro Brogi, Confronting America. The Cold War between the United States and the Communists in France and Italy, Chapel Hill 2011;

David Douglas Duncan, The Private World of Pablo Picasso, New York 1958

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS