M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

| MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM     We open this section on the history and theory of attribution, embedded into our Microstory of Art Online Journal, with a veritable thriller, not lacking, moreover, tragic and tragicomical elements. On the »Market for Merchant Princes« it was found in 1898 – the picture called since then the »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«, named after a legendary Roman high society lady, to whose life and times we already have dedicated a visual presentation, also to be found on this website (see: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/Spotlight5CircleOfMorelliOrTheThreeLivesOfDonnaLauraMinghetti ; and see also: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/DonnaLauraMinghetti). We open this section on the history and theory of attribution, embedded into our Microstory of Art Online Journal, with a veritable thriller, not lacking, moreover, tragic and tragicomical elements. On the »Market for Merchant Princes« it was found in 1898 – the picture called since then the »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«, named after a legendary Roman high society lady, to whose life and times we already have dedicated a visual presentation, also to be found on this website (see: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/Spotlight5CircleOfMorelliOrTheThreeLivesOfDonnaLauraMinghetti ; and see also: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/DonnaLauraMinghetti).The following is based on the paper that I delivered at the 2010 A Market for Merchant Princes: Collecting Italian Renaissance Paintings in America conference, presented at The Frick Collection by the Center for the History of Collecting in America, Frick Art Reference Library, New York (background picture: DS). The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«: Re-opening the Case |

The setting is Rome, one afternoon late in April 1898, and the weather is described as being »miserable«. A closed carriage, coming from a private Roman house and carrying two men and a very special cargo, stops at the grand hotel at Piazza Barberini. One of the two men is the American collector Theodore M. Davis (1837-1915), the other his advisor; and the cargo—a painting, believed to be by Leonardo da Vinci—is brought into the hotel. Much excitement in the circle of Theodore Davis. The advisor stayed for dinner.

What unfolds here(1) is the opening scene of a once famous, once notorious affair.(2) A trifle?—Maybe, or better—the whole world of turn-of-the-century connoisseurship in a nutshell.

A farce?—Partly, yes; but not without some tragic undercurrents; and despite many a splendid view certainly a worst-case-scenario of connoisseurship. For Bernard Berenson it was to become a nightmare, an ordeal; and the very basic facts should briefly be remembered:

Two years earlier Bernard Berenson had been the one to introduce this ›Leonardo‹ into the art-historical literature, had praised it, had praised it in the same breath with the Mona Lisa.(3) But the painting became only publicly known with Theodore Davis taking it from Rome to Florence,(4) Paris,(5) London,(6) and eventually to Newport (R. I.). As early as in May, the attribution was under question,(7) and at the turn of the century a new attribution, again supported by Berenson, had been established. The portrait was now to be considered as the work of a modern Tuscan painter named Angiolo Tricca, who had died in 1884,(8) hence ›not genuine‹,(9) or, if one likes so, a ›forgery‹.(10)

Berenson had changed his mind, but the case itself, an erratic incident, got never explained.(11)

On a more abstract level one might say that this is actually about two cases: There is—or was—the ›Leonardo/not Leonardo question‹. But if one considered this question—as Berenson did—as being answered in a negative sense, the problem shifted to the question, how it was possible that a painting, seen by many as ›appalling in its nullity‹ (if given the Leonardo-expectation)(12) had ever found his support. This is the worst case scenario, I was referring to: The ›Leonardo‹ on the Berensons’ list of ›sacred pictures‹ turned out to be ›not genuine‹ and ›appalling in its nullity‹.(13)

Since this is hard to believe, one might be inclined to look for the Leonardo again, secretly, assuming that underneath enamel might be gold. But I’d like to say right now that none of the chief protagonists ever claimed that Leonardo’s hand does not show at the visible surface at all. However,we will turn to the motif of the veil.

What I am going to do in the following is very simple. I am going to follow the journey of this portrait through its various environments, that is from Milan in 1880 to Gilded Age Newport. I am going to add three footnotes only (which are based on new archival research) to the setting of the beginning. My guiding question will be somewhat naive, but not simple: I am going to ask the various chief protagonists on what grounds this painting was to be attributed to Leonardo da Vinci—since I am not able to see it.

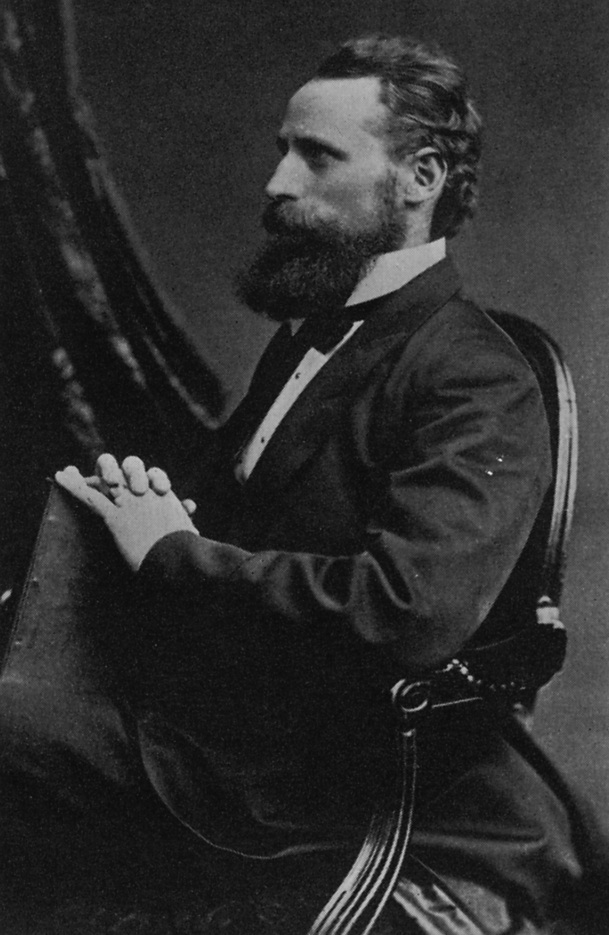

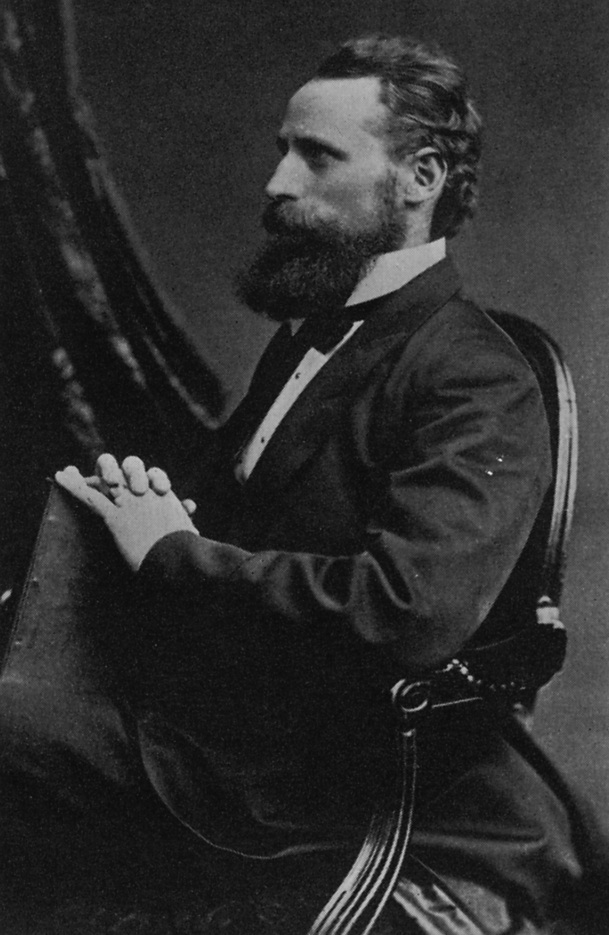

What happened might become at least a little more transparent, as we hear answers, and our starting point is the apartment of Giovanni Morelli in Milan, since the founding father of modern connoisseurship was the first owner of the portrait. No doubt—it is here, in this environment and in the very center of Milan, that the portrait had been loaded with meaning and significance.

*

One) One had to walk two flights of stairs to get into the apartment of Giovanni Morelli.(14) It is described as being rather Spartan—except for containing a splendid art collection. ›Giovanni Morelli lived like a king with gems all over his walls‹, one saying was, but his apartment can also be imagined as a ›bachelor’s cave‹.(15) A guest room contained at least six Old Masters.(16) And apparently Morelli’s bed room contained one painting only. We will come back to that. But for the moment: The only direct testimony we have of Morelli concerning the portrait is the wording of his will.(17) It reads as ambiguously as can be: A painting »believed to be a work by Leonardo« he bequeathed to a close friend. But who believed it and why? And the old assumption has to be reminded, that possibly all started with a jest.(18) We have at least and from the very beginning to consider Morelli’s jocular side, his sense of humour, his irony, his passion for literature and theatrical effect.(19)

A biography of Laura Minghetti, the friend, would lead us into the world of South Italian feudal nobility, through the history of unified Italy, seen from its inner circle of power (her husband was prime minister of Italy twice);(20) and last but not least into her famous Roman salon, one if not the center of Roman high society and the second environment for the portrait. One might imagine a large antique shop and add flowers everywhere, and then some more specific objects: A stuffed peacock on a chimney, the famous stairway leading into nowhere and orange curtains filtering the light falling in from outside.(21) The hostess, in Italian memory, enjoys the status of a legend.(22)

A certain mythology of connoisseurship (to which Berenson contributed) has it that being in her presence prevented one from seeing clearly, and tradition has given the role of the ›mysterious woman‹ to her.(23) But Laura Minghetti is actually the only protagonist who speaks quite frankly about her role in the affair. Surprisingly frankly, because my first footnote must read: The authenticity of the object in question is not even supported by the seller.

»Donna Laura Minghetti told me yesterday the whole story of the sale of the [so-called] picture by Leonardo da Vinci«, one reads in the diary of a close acquaintance.(24) To sum it up: Laura Minghetti had no knowledge of a ›Leonardo‹ at all. An offer had been given (by an American), an offer had been taken; and the diarist clearly understood, that Laura Minghetti knew, that Morelli had not considered the painting as a work by Leonardo.

It might be a little bit too strong, however, to say that the authenticity is vetoed by the seller. What Donna Laura revealed in private is that she had taken advantage from a cloud of ambiguity. The point is not that she did interfere with attribution, the point is that she did not. And again the problem is shifting to the question why there was genuine belief on the side of experts. And if Giovanni Morelli had ›imposed a hoax‹(25) upon his followers, how had he managed to do that?

Two) We have—this is my next footnote—to come back to the second man in the carriage, Theodore Davis’ advisor, and it cannot be stressed enough that it was not Bernard Berenson.(26)

It adds not a little drama to this affair that the man who had advised Theodore Davis in this case represented both Leonardo scholarship and Morellian connoisseurship. To the German-born art critic Jean Paul Richter (1847–1937) Leonardo-philology owes much;(27) and in the history of connoisseurship Richter played a double role, to say the least. Representing a generation between Morelli and Berenson in the family tree of connoisseurs, he had been an disciple and ally of Morelli, and he had introduced Bernard Berenson to connoisseurship. But one should add that he never stepped out of Morelli’s shadow and was certainly eclipsed by Berenson.(28) His role in the case has never been visible, but archival findings allow us to follow the events a little further and then to return to Milan where all had begun. The facts are as follows:

(Picture: pinterest.com)

In the year 1907 Jean Paul Richter’s one daughter, who had just begun her career as a museums archaeologist at the Metropolitan Museum, visited Newport.(29) Theodore Davis, in the meantime, had become a ›maecenas‹ of excavations in the Valley of the Kings, and thus his Jacobean-style mansion at Ocean Avenue—the third environment of the picture—a bridgehead of Egyptology at the very surf of the Atlantic.(30)

But the Leonardo-matter had not fallen into oblivion,(31) and apparently one made Gisela Richter feel that not all was to the best. This ›inspired‹ her father to write down a ›memorandum‹ for Theodore Davis on behalf of the painting and its history, exactly ten years after the sale; and this vindication is extant and ironically kept in Rome.(32) My third footnote is meant to introduce it as a source.

Three) What line of ›defense‹ would Richter choose, long after Berenson’s change of mind (the painting was now hung opposite to Mr. Davis’s desk and could be scrutinized)?(33) In one word: It is a ›living history-approach‹. Richter is leading us back into Morelli’s apartment in 1880 and we are led to walk the two sets of stairs again. In recreating the atmosphere he prepares the reader, that is Mr. Davis,(34) for the main argument, which is—to quote Morelli from memory.

We are informed that the painting in question was chosen as the »sole ornament« of Morelli’s »somewhat Spartan bed room«, hung so that Morelli could see it from his bed.(35) At the very bottom of this affair again something as ambiguous as it can be. But the very core of the affair is language, a rhetoric of repainting, and I’d like to quote an excerpt of Richter’s account:

»Often however, as I stood before it in admiration, have I wondered that Morelli—in view of the rarety of easel pictures by Leonardo, did not hang his treasure in a place of more general access, where it might delight more admirers.

One day I ventured to express my surprise, and [I] have a vivid recollection of the conversation which ensued. He shook his head. ›It is not a picture for the herd‹, he said; then drawing my attention to the circumstance that it had been much re-touched added: ›these retouches could easily be removed, but the process is a dangerous one, and I prefer to keep the lovely thing, as it is, for myself, and for those whom I think worthy. These retouchings are obvious; they do not however conceal the master’s soul, they only veil it; there may be some however who lacking love and knowledge fail to see through the veil to the beloved features behind. So it hangs well—here‹!«

*

(Source: De Marchi, Falsi Primitivi, p. 183)

I am going to try now to put all this into perspective.

First of all: Significant for this case—and this although an inner circle of the Morellians is gathered here—is the total absence of everything Morellian connoisseurship stood for. Morelli, Richter and Berenson, in their very individual ways, were commited to a project of rationalizing connoisseurship. But not in Richter’s defense nor elsewhere has it ever been made explicit why and how exactly artistic individuality revealed itself in the visual detail, and how master was to be distinguished from follower, from Flemish copyist, or from modern forger. The standard is lowered here to mere opinion-giving, and judged by Richter’s own scientific standards—and his central notion was ›objectivity‹—there is simply nothing there.(36) Not one rational reason, not one good reason, and no tool of connoisseurship was apparently ever applied. Instead, the metaphor of the veil and the weight of Morelli’s word.

The case—unique rather than representative in many regards(37)—reads as being deliberately designed to discuss one element of connoisseurship especially, and this is the role of authority, and particulary of what a sociologist would call ›charismatic authority‹ (people follow a person because they ascribe special skills to that person).(38) One could stick to this interpretation, even if the Leonardo would still be found, or the good reason, or the fragment of a fingerprint.(39)

I have not spoken much about Bernard Berenson, but to sum up what I consider a likely course of events in this case, involving two Olympians and a kind of mercurial messenger, is the right moment to reconsider his role: I do believe that in the beginning was nothing but Morelli playing a trick on somebody (a trick of which Laura Minghetti knew and was later reminded of by the phrasing of Morelli’s will).(40) Morelli imposed a hoax only upon his followers, and at least Jean Paul Richter, early in his career, was taken in, probably by a Morellian rhetoric of repainting as we have heard (and which is ubiquitous, exept for the fact that Morelli, if referring to overpainting, used to speak of the ›mask‹ and not of a ›veil‹).(41) Richter succumbed to the temptation—this is another footnote—to mention the painting in print eleven years prior to Berenson,(42) and passed on to the latter was what I would call an apocryphal Morellian tradition about what Morelli had really believed. Passed on, as it appears, it was by Richter in good faith.(43) Thus in the early 1890s and at an early stage of his career Berenson simply allowed leading authorities—who represented both Leonardo-scholarship and connoisseurship—to define his notion of Leonardo.(44) What he saw—at least a photograph—,(45) he saw in the light of this questionable tradition. A full discussion would further speak of the motif of ›being one of the few worthy‹ (and of the fatal lure it meant),(46) of the impact of a mighty Leonardo-myth,(47) and of a long and multi-faceted aftermath of an affair which almost ruined Berenson’s career.(48)

The very core of this affair seems to be the language of authority, and if the rhetoric of repainting had been passed on to Berenson—as a rhetorical environment and as a part of this apocryphal tradition—is not quite clear.

In ’96 Berenson had suggested to the public that the ›Leonardo‹ was visible for everyone with eyes to see.

In ’98, after seeing the portrait again (or for the first time, if he only saw a photograph earlier on), he wrote to Isabella Stewart Gardner: »Only to see [Leonardo’s] hand in it nowadays one must know Leonardo as I know him, or know nothing at all and take it on faith.«(49)

(Picture: moviepilot.de)

This rhetoric is neck-breaking and the shift dramatic (and the improvisation probably worthy of the talented Mr. Ripley).(50) But the theory of the veil is actually in accordance with both positions, since apparently no-one ever defined which parts exactly had to be considered as the un-leonardesque veil and which as leonardesque. The theory leaves room to say that what we see is Leonardo, or to say: ›Leonardo’s hand is almost entirely invisible, but we can still see a hand‹ and, in some sense, the unknown, the utopian, the imaginary masterpiece. It is possible that Berenson came to understand the ambiguity of this rhetoric of overpainting only too late to defy it. Nevertheless, he was to use a similar pattern of thinking as his last straw, before he began to see a fake (and he was to use the veil-metaphor, referring to repainting, himself, in an essay of this very summer).(51)

(Picture: hans-christian-andersens.blogspot.com)

If, despite tragic undercurrents, in the beginning was nothing but a jest, a fictitious Leonardo, a staged cult of the precious and the rare, and possibly a sparkling in Morelli’s eyes, one should try to make this more plausible, since most of what we know is based on Richter’s account only, which was meant to show Morelli’s seriousness. Yet something of Morelli’s jocular side,(52) a possible signal of irony, appears to shine through.

In the first lines of his Italian Painters of the Renaissance Bernard Berenson is referring to the fairy tale of the emperor’s new clothes and I am borrowing this reference to literature.(53) What was Morelli saying again? ›Some, lacking love and knowledge, might not be able to see the Leonardo‹. This is nothing but the rhetoric of the deceitful weavers in Andersen’s fairy tale, who argue: ›Some, not fit for their office, might not be able to see the emperor’s new clothes.‹

If it began with this, if the veil is obsolete, and if in the end there’s nothing there—which means: nothing but environments, nothing but the cultural energies of connoisseurship and collecting around a vacancy, left by the vanishing of a fetish-like object—if this is it, I have just told the story of the emperor’s new clothes transposed into connoisseurship. And one might conclude: Giovanni Morelli did not only provide us with a more rational approach to connoisseurship; he also did provide us with an example about how authority is guiding perception and about how far it can lead. The cargo of the closed carriage turns out to be a warning example, sinister and farcical at the same time, and coming through from time to time is the human drama in three lives of connoisseurs.

(Picture: philosophyofscience.blogspot.com)

Annotations:

1) See Emma B. Andrews, A Journal on the Bedawin 1889–1912. The Diary kept on board the dahabiyeh of Theodore M. Davis during seventeen trips up the Nile, 2 volumes, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [dated 1919], entry for April 20th, 1898 and passim), a source used by Berenson-biographer Meryle Secrest (see Secrest 1980, p. 425, note to pp. 128f.), yet—surprisingly—not for her reading of the case (p. 205ff.). (back)

2) See primarily Pantazzi 1965. Also: Reinach 1912, especially p. 19ff. and De Marchi 2001. (back)

3) See Pantazzi 1965, p. 334f. (back)

4) Where it was shown to Bernard Berenson and Mary Costelloe (Mary Berenson, Diaries, The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, Florence, entry for April 26th, 1898). Compare also: Mather 1912, p. 44. I do not consider this fictionalized account a source to rely on. (back)

5) In Paris the painting was taken to the Louvre—›the owner carrying the panel‹—for a side by side comparison (see Reinach 1912, p. 20). (back)

6) In London the painting was on display for ›some 24 hours‹ at the Burlington Fine Arts Club. See Elliott 2000, pp. 205ff. [appendix]. It appears, since Murray could scrutinize the painting during this period of time, that he is also to be considered as the author signing as ›curator‹, whose letter spreading some notes ›made in front of it‹ (and referring to the back of the panel as well) was published in 1904 (see [Amateur] 1904). (back)

7) See Jean Paul Richter to Bernard Berenson, May 27th, 1898, The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, Florence. (back)

8) This attribution might be mainly based on the fact that the Milanese restorer Luigi Cavenaghi informed Berenson about the real author (see Reinach 1912, p. 20; and compare Samuels 1981, p. 252). Unfortunately, no original testimony of Luigi Cavenaghi is available. Berenson informed Davis at the end of 1899 that the painting was a fake (see N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, p. 196f.). Mary Berenson later referred to the painting as the »Tricca-Leonardo« (see Mary Berenson, Diaries, The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, Florence, entries for October 10th and 11th, 1903). This attribution, although endorsed by De Marchi, is not as convincing as it should be (which is not to say that the Leonardo-attribution is favored here again). For Tricca see also Alessio et al. (Ed.) 1993). (back)

9) ›Not genuine‹ could be understood in the context as ›not even an attempt to deceive‹. Compare Elliott 2000, p. 154f. and p. 209. (back)

10) Whether the painting was meant to deceive at all is not known. The notion of forgery does not necessarily apply. (back)

11) Pantazzi assembled the general facts and especially did much to analyze pieces of fiction based on the case (Paul Bourget; Frank Jewett Mather, Jr.), but did not attempt to solve it. (back)

12) The formula ›appalling in its nullity‹ is inspired by Mather 1912 (p. 29: »Its [the chef d’œuvre’s] nullity was appalling«) and used here as epitomising the tradition of a very harsh dismissing of what one might call—if the picture is taken out of the specific context—a faint realisation of an Early Renaissance profile portrait type. (back)

13) The painting appears with a ›Newport location‹ (see Pantazzi 1965, p. 336 and p. 345f.), probably put in after Berenson had seen the portrait (again) in Florence at the end of April 1898. (back)

14) See Seidlitz 1891. (back)

15) Compare Diary of Louise M. Richter [›Mrs. Jean Paul Richter‹], No. 2, The Jean Paul Richter Papers, [formerly Duke University, Durham, now:] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Onassis Library, entry for August 11th, 1885 (the saying was originally by Henriette Hertz); see also Münz 1898, p. 86 and p. 99f. (back)

16) See Richter / Richter (Ed.) 1960 , p. 128f. (back)

17) It is reproduced in Zeri / Rossi 1986. See also De Marchi 2001, p. 189, note 132 (»creduta opera di Leonardo da Vinci«). (back)

18) See Pantazzi 1965, p. 343. (back)

19) See Panzeri / Bravi (Ed.) 1987, p. 84 (a 4-volume history of comical literature as well as a history of the court jesters are listed here as once being part of Morelli’s library). (back)

20) Morelli spoke of his ›ingenious and utmost lively friend‹ (see Giovanni Morelli to Jean Paul Richter, November 4th, 1881, Nachlass Jean Paul Richter, Bibliotheca Hertziana, Rome). For a certain ›magnetism‹ between the two see Agosti 1985, p. 56 and passim. (back)

21) See Morani-Helbig 1953, p. 150f. How exactly the portrait was shown in this environment is not known. (back)

22) A critical biography does not exist, despite—or because of—the legendary status of Laura Minghetti. A fine psychological portrait—embedded in a sociology of Roman interior decors—is given in Morani-Helbig 1953, p. 149ff. See also Pantazzi 1965, p. 331ff. for further references. The circle of Theodore Davis visited the house by appointment (see Andrews, Journal (as in note 1), entry of April 18th, 1898). (back)

23) The inner logic of Mather’s story has it that the aura of the enchanting woman is crucial to explain the error of the Berenson-character (see Mather 1912, p. 41ff.). But even on the level of the fiction it is not the only element of the explanation. Significant is the element that is not mentioned (or omitted)—probably because it would undermine the inner logic: the existence of a photograph of the painting which Berenson had owned in 1896 and had lent to Salomon Reinach not without some restrictions of use (see Reinach 1912, p. 20; see also N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, p. 139). (back)

24) See [Mary Enid Layard] ›Lady Layard’s Journal‹ [diary of Mary Enid Evelyn Layard], Online-edition retrievable under http://www.browningguide.org [the original is in the British Library, London], entry for February 22nd, 1899: »[…]. As she had admired the picture in his rooms & he had given only a few francs for it at Florence & knew that altho’ a pretty thing it was not by Leonardo he had given it to Donna Laura. She had given it to her daughter Mme de Bülow but it remained with Donna Laura here. One day Mr J. P. Richter a pupil of Morelli’s & now a picture dealer of not very good repute asked Da Laura’s permission to take a friend to see her pictures— This she gave & a day or two after Richter wrote to say that his friend (an American) offered her 5,000 francs for the »Leonardo.« She telegraphed to ask her daughter & they took the offer—Richter having stipulated for his percentage. Richter must have known as well as Mme Minghetti what had been Morelli’s real opinion of the picture, but he did not scruple to sell it to the American for this enormous sum— […].«—The actual price for the painting was rather 60,000 (or even 70,000) francs, equalling 3000 pounds of the time (see N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, p. 139 and Mary Berenson, Diaries, The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, Florence, entry for April 26th, 1898; see also Secrest 1980, p. 205).— See also the entry for September 8th, 1901, in the diary of Lady Layard because of her telling the story to others. (back)

25) This formula again is inspired by Mather 1912 (p. 44: »imposing it upon his followers as a hoax«). It is the assumption of the character in the story that is modelled after Berenson. (back)

26) It is still mentioned in recent literature as a possibility (see Elliott 2000, p. 155). Meryle Secrest was the first to mention a source saying that the advisor had been Richter (see Secrest 1980, p. 205 and p. 435). The mere fact is established by Richter himself (see the above mentioned letter to Berenson), by Andrews, Journal (as in note 1) and by the above quoted excerpt from the diary of Lady Layard. (back)

27) For Jean Paul Richter see my Das Schlaraffenleben der Kunst (http://www.amazon.de/Schlaraffenleben-Biografie-Kunstkenners-Vinci-Forschers-1847-1937/dp/3770556402/ref=pd_rhf_dp_p_img_1_VS2M). (back)

28) See Seybold 2014. (back)

29) See Jean Paul Richter Diary 1903–1907, The Jean Paul Richter Papers, [formerly Duke University, Durham, now:] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Onassis Library, entry of July 22nd, 1907. (back)

30) For Davis’ role in Egyptology see Hankey 2001, passim, and Reeves 2001, pp. 113ff. (back)

31) At the very moment Richter is providing his memorandum the first objects related to King Tutankhamun were discovered in the Valley of the Kings by Davis’s men (see Reeves 2001 , p. 117). (back)

32) See Archiv der Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte, Rome, Nachlass Jean Paul Richter, box 8, folder 3. Extant are German drafts, an English version, most likely by the hand of Alicia Cameron Taylor, Richter’s assistant, and a typoscript, probably done later. See the appendix below for a transcription of the handwritten English version. (back)

33) For ›opposite to the desk‹ see Mary Berenson, Diaries, The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, Florence, entry for October 10th and 11th, 1903. (back)

34) It appears that Theodore Davis got the sending, because Richter apparently got a reply, which, however, is not extant. See Jean Paul Richter, Diaries 1907–1908 and 1908, The Jean Paul Richter Papers, [formerly Duke University, Durham, now:] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Onassis Library, entries for March 3rd and May 25th and 26th, 1908. (back)

35) Richter is the only one who ever referred to this particular display.—Compare N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, p. 135 (for ›halo of mystery and unapproachableness about the painting‹). (back)

36) Compare, for example, Richter 1887. (back)

37) Representative might be the general tendency of replacing the painstaking rationality of the good reason by mere opinion-giving. (back)

38) One of the most classical notions of the very classic of German sociology: Max Weber. (back)

39) Concerning the last sighting of the picture see Secrest 1980, p. 206 (and p. 435, with the corresponding note); see also The New York Times of June 22nd, 1966 (obituary for the Baroness de Schaeck).—What remains is the strong doubt that there ever was and that there will ever be found a ›Leonardo‹ (which is not, however, to be equalled with a certainty gained by applying every possible tool of connoisseurship). (back)

40) According to Meryle Secrest, Berenson would later take his cue from Morelli in beginning to test visitors‘ eyes upon forgeries (see Secrest 1980, p. 214f.; a reference, however, is not given for this). (back)

41) Compare only Richter / Richter (Ed.) 1960, p. 462, 486 and 530. (back)

42) See Richter 1885; the portrait is mentioned in column 711 (›a precious portrait of a girl, seen in profile, in a private collection outside of Germany‹); see also Louise M. Richter, Diary No. 2, The Jean Paul Richter Papers [formerly Duke University, Durham, now:] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Onassis Library, entry of August 13th, 1885. (back)

43) See Seybold 2014 for a discussion of the Richter-Berenson relationship.—The Berenson-character in Mather (Mather 1912, p. 36) refers to ›those whose opinion is sought‹, who apparently had considered the painting as a ›superlatively lovely thing‹.—The possibility that Richter commited an obvious fraud has to be considered (compare the diary of Lady Layard for this assumption), but I cannot detect any indication for this in letters or diaries. (back)

44) As this becomes obvious, the error does appear far from being absurd, since everyone active in scholarship is aware how delicate it is to challenge leading authorities. (back)

45) Whether Berenson had really seen the painting on location in Rome is uncertain. The actual owner, as Laura Minghetti revealed (see above), was her daughter Maria von Bülow, and the actual designation given by Berenson in 1896 might have been inaccurate even at the time. But since it is not known when exactly the painting was given to Maria von Bülow, this has to remain open. (back)

46) Compare Mather 1912, p. 36 (›to have seen it was a distinction‹). (back)

47) If a cultural object is linked to Leonardo, whole cultures tend to expect the highest forms of human expression. Expecting it is only one step away of seeing it. However, if the link gets cut again, as is the case here, the object, although physically unchanged, falls into oblivion. (back)

48) Berenson’s ordeal in some sense began with the various questions Isabella Stewart Gardner had (see N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, pp. 135ff., 141, 143, 151). In the long run the case affected the relation to various American collectors, especially because Charles Fairfax Murray tried to build a case against all the Morellians. Beyond that it certainly affected Berenson’s thinking about (the Morellian) method, and about Leonardo, but even more so, about the Leonardo-myth. (back)

49) N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, p. 139.—One has to consider that in the very summer of 1898 Berenson was already ‘almost suicidal’ over business relations with Mrs. Gardner (see Mary Berenson, Diaries, The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Berenson Archive, Villa I Tatti, Florence, entry of June 23rd, 1898), and this for very different reasons. (back)

50) It probably was Berenson’s luck that Mrs. Gardner, seemingly, did not care about his dramatic inconsistencies. She went to see ›the Leonardo‹ and found the picture ›lovely‹ (N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987, p. 151). (back)

51) See Berenson 1902, p. 23 [originally printed in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts of July 1898; see Samuels 1981, p. 438]. (back)

52) I tend to think that in all this—as far as Morelli is concerned—the mere fact is hidden (and at the same time exposed) that he lived as a bachelor all his life, who neither used his empty walls for a cult of sentimentality nor for a cult of the precious and the rare (but for something else and while evoking both possibilities). (back)

53) Berenson 1952, p. VII (first paragraph of the preface). (back)

Appendix: The ›Minghetti Memorandum‹

(published with kind permission of the Bibliotheca Hertziana from the Archiv der Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte, Rome, Nachlass Jean Paul Richter, box 8, folder 3)

A profile bust in oil colours of a blonde girl turned to the left was bought in Rome in 1898 by Mr. Davis of Newport[.] from Donna Laura Minghetti, to whom it had been bequeathed by the late Giovanni Morelli, senator ot the kingdom of Italy, a man esteemed and loved by a large circle of distinguished friends, & an art-critic of unapproachable acumen, whose writings published towards the end of his life under the pseudonym of Ivan Lermolieff inaugurated a new era in connoisseurship, & revolutionized art-history.

In 1880 I had the pleasure & honour of spending two months with him in Milan as his guest, while I was studying the MS. of Leonardo da Vinci, & saw this picture then for the first time.

His appartment was full of pictures & other remarkable works of art; the largest of his rooms however, his bed room, contained one picture only, the little portrait in question, & that was so placed that he could see it from his bed.

It is difficult to believe that a painting of doubtful authenticity could have yielded such intimate pleasure to a critic of Morelli[’]s calibre, that he not only selected it as the sole ornament of his somewhat Spartan bed room, but hung it so that it should daily gladden his awakening eyes.

Often however, as I stood before it in admiration, have I wondered that Morelli—in view of the rarety of easel pictures by Leonardo, did not hang his treasure in a place of more general access, where it might delight more admirers.

One day I ventured to express my surprise, & [I] have a vivid recollection of the conversation wh[ich] ensued. He shook his head. »It is not a picture for the herd«, he said; then drawing my attention to the circumstance that it had been much re-touched added: »these retouches could easily be removed, but the process is a dangerous one, & I prefer to keep the lovely thing, as it is, for myself, & for those whom I think worthy. These retouchings are obvious; they do not however conceal the master’s soul, they only veil it; there may be some however who lacking love & knowledge fail to see through the veil to the beloved features behind. So it hangs well—here«!

As to the date at which Morelli acquired it: he told me, I remember[,] that it was among his first acquisitions; now, he began to collect 1856.

Only a few months ago I asked his old & valued fried, Marchese Visconti Venosta[,] if he knew when Morelli bought the portrait-bust bequeathed to Donna Laura Minghetti, to which he replied, that the senator had had it as long as he knew him. This Italian statesman who was foreign minister in 1870, was one of Morelli’s most intimate friends, & inherited his invaluable collection of photographs. The early date at wh[ich] Morelli was in possession of this portrait is only of importance as disproving an assertion wh[ich] obtained credence in a certain circle, that it is the work of the Roman painter Gioja.

In my opinion it is a sketch by Leonardo da Vinci, which was finished towards the close of the cinque cento by an artist of the calibre of a Matteo Roselli; this artist,—whoever he may habe been[—]scrupulously respected the contours of the sketch he was bold enough to complete, & was doubtless lifted above his normal level by the beauty which shines victoriously through the veil, possibly the preserving veil, which he has spun about it.

Bibliography:

Agosti 1985

Giacomo Agosti, Giovanni Morelli correspondente di Niccolò Antinori, in: Quaderni del Seminario di storia della critica d’arte 2 (1985) [Studi e ricerche di collezionismo e museografia. Firenze 1820–1920], Pisa 1985, pp. 1–83

Alessio et al. (Ed.) 1993

Martina Alessio et al. (Ed.), Angiolo Tricca e la caricatura toscana dell’ottocento, [catalogue] Firenze [Giunti] 1993

[Amateur] 1904

[Amateur], [Letter to the Editor], in: Magazine of Art, January 1904, p. 447

Berenson 1902

Bernhard Berenson, Alessio Baldovinetti and the New »Madonna« of the Louvre, in: ibid., The Study and Criticism of Italian Art, Second Series, London [G. Bell and Sons, LTD] 1902, pp. 23–38

Berenson 1952

Bernard Berenson, Die italienischen Maler der Renaissance, Stuttgart [Stuttgarter Hausbücherei] 1952

De Marchi 2001

Andrea G. De Marchi, Falsi Primitivi: negli studi, nel gusto; e alcuni esempi, [Thèse Lausanne], Turin/London/Venice [Umberto Allemandi] 2001

Elliott 2000

David B. Elliott, Charles Fairfax Murray. The Unknown Pre-Raphaelite, Lewes/New Castle [Oak Knoll Press] 2000

Hankey 2001

Julie Hankey, A Passion for Egypt. Arthur Weigall, Tutankhamun and the »curse of the pharaohs«, London [Tauris] 2001

Mather 1912

Frank Jewett Mather, Jr., The del Puente Giorgione, in: ibid., The Collectors. Being Cases mostly under the Ninth and Tenth Commandments, New York [H. Holt and Co.] 1912, pp. 27–54

Morani-Helbig 1953

Lili Morani-Helbig, Jugend im Abendrot. Römische Erinnerungen, Stuttgart [Victoria Verlag] 1953

Münz 1898

Sigmund Münz, Giovanni Morelli. Ivan Lermolieff, in: ibid., Italienische Reminiscenzen und Profile, Wien [Leopold Weiss] 1898, pp. 86–105

N. Hadley (Ed.) 1987

Rollin van N. Hadley (Ed.), The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner 1887–1924, Boston [Northeastern University Press] 1987

Pantazzi 1965

Sybille Pantazzi, The Donna Laura Minghetti Leonardo. An International Mystification, in: English Miscellany 16 (1965), pp. 321–348

Panzeri / Bravi (Ed.) 1987

Matteo Panzeri / Giulio Orazio Bravi (Ed.), La figura e l’opera di Giovanni Morelli: materiali di ricerca, Bergamo [Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai] 1987

Reeves 2001

Nicholas Reeves, Faszination Ägypten. Die großen archäologischen Entdeckungen von den Anfängen bis heute, Munich [Frederking & Thaler] 2001

Reinach 1912

Salomon Reinach, New Facts and Fancies about Leonardo da Vinci, in: The Art Journal 28 (1912), pp. 6–25

Richter 1885

Jean Paul Richter, Der angebliche Leonardo da Vinci in der Berliner Gemäldegalerie, in: Kunstchronik No. 43 und No. 44 (September 10th and 24th, 1885), columns 709–712 and 729–733

Richter 1887

Jean Paul Richter, Recent criticism on Raphael, in: The Nineteenth Century 22 (September 1887), pp. 343–360

Richter / Richter (Ed.) 1960

Irma Richter / Gisela Richter (Ed.), Italienische Malerei der Renaissance im Briefwechsel von Giovanni Morelli und Jean Paul Richter 1876–1891, Baden Baden [Bruno Grimm] 1960

Samuels 1981

Ernest Samuels, Bernard Berenson. The Making of a Connoisseur, Cambridge, Mass./London [Belknap Press] 1981 [fourth edition]

Secrest 1980

Meryle Secrest, Being Bernard Berenson. A Biography, London [Weidenfeld & Nicolson] 1980

Seidlitz 1891

Woldemar von Seidlitz, Giovanni Morelli †, in: Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft 14 (1891), pp. 347–350

Seybold 2014

Dietrich Seybold, Bernard Berenson and Jean Paul Richter: The Giambono’s Provenance, in: Joseph Connors / Louis A. Waldman (Ed.), Bernard Berenson: Formation and Heritage, Villa I Tatti Series 31 [Dumbarton Oaks Publications/Harvard University Press] 2014, pp. 19-31

Zeri / Rossi 1986

Federico Zeri / Francesco Rossi, La raccolta Morelli nell’Accademia Carrara, Cinisello Balsamo [Silvana] 1986

As to the detailed picture credit for the picture of Morelli used on this website see: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/ForthcomingGiovanniMorelliAPortrait .

Detailed picture credits for the portrait of Donna Laura Minghetti is given here: http://www.seybold.ch/Dietrich/Spotlight5CircleOfMorelliOrTheThreeLivesOfDonnaLauraMinghetti .

And as to the detailed picture credit for the picture of Jean Paul Richter see my Richter biography, wherin you also find more informations on the history of the so-called »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo« (see: http://www.amazon.de/Schlaraffenleben-Biografie-Kunstkenners-Vinci-Forschers-1847-1937/dp/3770556402/ref=pd_rhf_dp_p_img_1_VS2M).

(Picture: pinterest.com)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS