M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

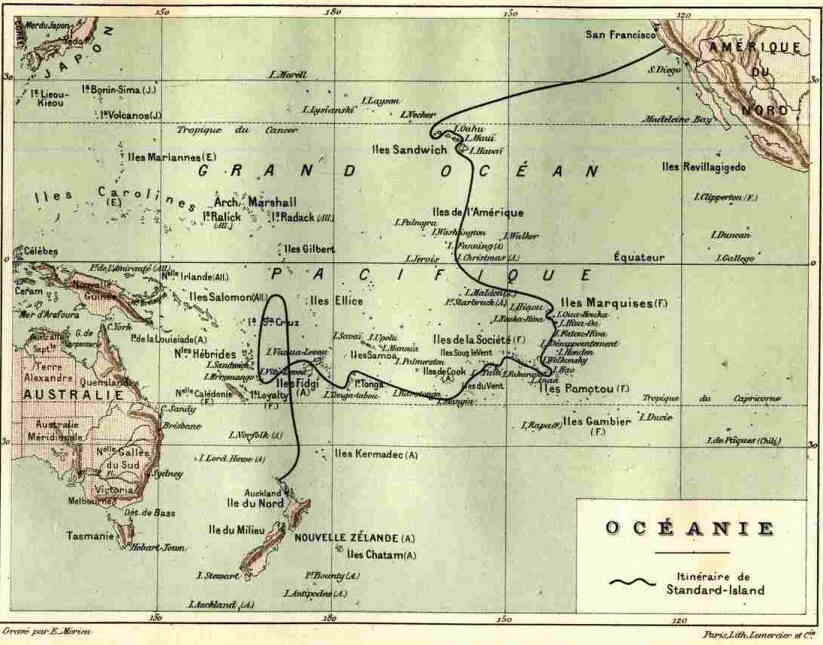

THE LEONARDO DA VINCI ARCHIPELAGO

(Picture: j-verne.de)

THE PROPELLER ISLAND

For THE VIRTUAL LEONARDO DA VINCI RESEARCH INSTITUTE see here.

For THE VIRTUAL LEONARDO DA VINCI RESEARCH INSTITUTE see here.And for the ARCHIVE to the ARCHIPELAGO and to the INSTITUTE see here.

Now opened (16 September, 2015) – the online exhibition Leonardo’s Pen, dedicated to the ways Leonardo da Vinci inspired and influenced 20th century writers, poets and inventurers. Welcome!

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM edited by DIETRICH SEYBOLD  LEONARDO’S PEN |

(Picture: acmestudio.com; cover picture, above: DS)

›Boots‹, ›socks‹, a ›comb‹, a ›towel‹, ›shirts‹, ›shoelaces‹, ›shoes‹ –

in c. 1510 Leonardo da Vinci, once again, once more did pack his things. At least it does appear so, because these were things, objects that he noted, enlisted on a sheet (Windsor 19070b).

As well as a ›penknife‹ and ›pens‹. As well as a ›skin over the chest‹, ›gloves‹, ›paper bags‹ (in the Renaissance were paper bags in use – who would have thought that). And finally ›charcoals‹.

Pens and penknifes appear repeatedly in such lists of objects that Leonardo, if about to travel, was about to pack. But what do we know about Leonardo’s penknife, his pens, or his pen?

Not much, as it appears. Although it was the writing Leonardo, the pondering Leonardo (was he pondering about what exactly to take with him, every time?), the musing Leonardo has become part of our imagination of Leonardo, and this due to the study of Leonardo’s notes, begun actually rather late, namely in the late 19th century.

And since it has become a commonplace to say that our pens contribute to our thoughts (whole academic industries have built on this rather simple thought by Nietzsche), one might also ask what pens did contribute to the writing of Leonardo, to the image of his mind that, much less obvious in his paintings, does manifest itself in writing, drawing, in pondering (a pondering that might be represented by the white space on a sheet).

This exhibition, my first Leonardo exhibition as a virtual curator, is dedicated to Leonardo’s Pen. And this means to the image of a writing Leonardo, who, as a writer did inspire 20th century poets. This Leonardo is less known, and we would like to make him known better, and to show how the ›flights of the mind‹ did inspire writers and poets, particularly writers and poets.

But not only poets: since we do know that the technology that is in use today does contribute to our thoughts (perhaps in shaping our thoughts, perhaps in offering ideas like google does offer search terms to us, even if our pen, our hand has not yet figured out what exact term to search for), we might, for once, ask how Leonardo did contribute to this pen, this technology we use. Since Leonardo did inspire the 20th cenutry inventurers. The thinking, the pondering, the drawing Leonardo – and less the painting artist – did indirectly contribute to 20th and 21st century technologies of writing, to our pen, since he did inspire those who made them (and allowed me to turn right-handed Erasmus into a left- or both-handed Leonardo below).

MICROSTORY OF ART ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM edited by DIETRICH SEYBOLD |

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen I –

Lila Tretikov

(Picture: sopitas.com)

(Picture: prbm.com)

›My personal hero is Leonardo da Vinci‹, the executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation, Lila Tretikov, recently said in an interview (published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung am Sonntag, 1 February 2015). And: ›Again and again I do enjoy to think about how his immeasurable intellect might have worked. For me art and science are no contradiction but one and the same thing.‹

What better opening statement would there be to find, than this statement by Lila Tretikov (who also might be considered as a ›Renaissance-type‹ or ›woman‹, someone uniting many diverse capacities in his person). The ›intellect‹ of Leonardo da Vinci, or his ›mind‹, how might it have worked? And raising this questions means also pointing to the rather little known fact that Leonardo studies are actually quite young. Because only the 19th center embarked on studying, as systematically as possible (but how systematical is that?), the many dispersed notes by Leonardo. How did Leonardo’s intellect work (and how did or does anyone’s intellect work)? And how attempting to answer such questions? And who might be the one to answer it?

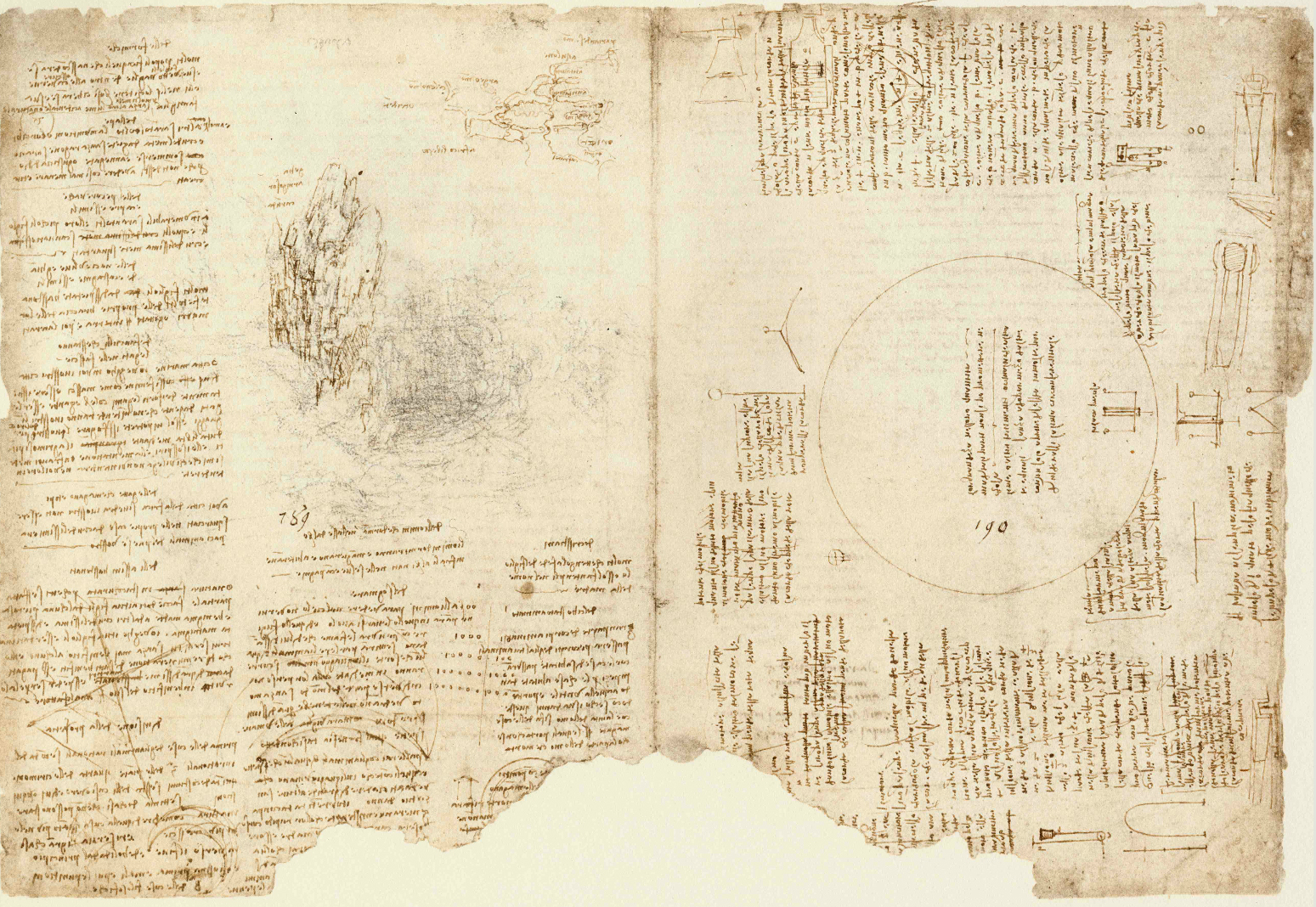

We should mention that, roughly, several thousand pages with notes by Leonardo do exist that we would have to study, if we consider these notes, those ›literary works‹, penned down by Leonardo – but penned down might not be the right word, because his pen was sort of dancing, drawing, writing, calculating, scribbling, doodling… resting –, if we consider these notes as the primal source to study Leonardo’s mind. Was also this pen thinking? Was this pen contributing to Leonardo’s thinking. All questions that can easily be raised. But if you delve deeper into these questions, all certainties easily dissolve.

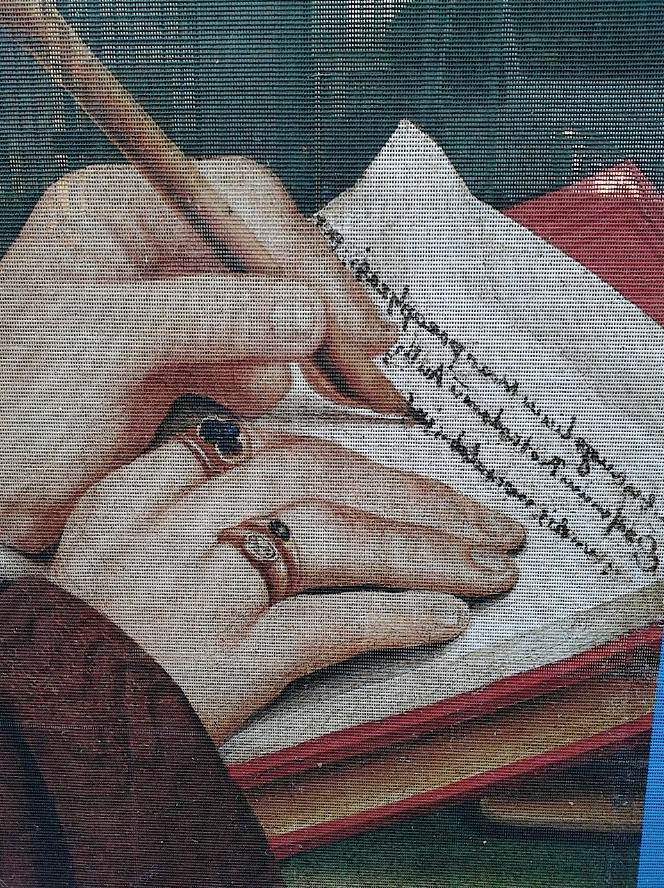

The faint sketch of a hand, holding a pen (or a brush?)

from Codex Atlanticus 770v [ex 283vb]

(source: leonardodigitale.com)

And in the era of digitization (and in the era of the honorable Wikimedia Foundation) we have to keep in mind that usually people that have become interested in Leonardo either want to go to the sources (usually in faksimile) ›directly‹, or they consult anthologies with Leonardo’s writings and notes. And this latter approach does lead directly into the history of Leonardo studies and edition. A fascinating story, but also a story that may make you aware that the Leonardo da Vinci that you get is formatted. Pre-formatted, because somebody has edited, commented, structured, reorganized a material (the manifestations of Leonardo’s pen on paper, once fluid, now fixed, in more than one sense). Since this material was, as Leonardo himself knew, rather unstructured, something that yet had to be brought, or at least potentially could be brought into a certain order (or has it not? and is just the fluid quality the actual quality of that intellect that was, rather obsessively, also drawn to water?).

Does intellect mean order at all (or permanent reorganization?). We might say that intellect means possibility, the permanent reorganizing of possibilities (within the space of everything that is possible). It means to arrange data, to pre-format, to format. And we may look at the history of Leonardo interpretation as a history of people deciding about to structure Leonardo’s mind, his thoughts, his intellect. By interpreting. By formatting. By teaching other people about Leonardo. ›Formatting‹, it does seem to me, could be the proper word, but of course also this word is nothing else than a tool to structure something (here the history of Leonardo edition). In hindsight, because one of the European minds to think about Leonardo’s mind was French poet and writer Paul Valéry. Who certainly did not know about what meaning, once, the term ›formatting‹ would have, when he began writing, in 1894, on Leonardo.

But after roughly a hundred years of technological progress (and also after roughly hundred, only hundred years of systematic Leonardo studies) formatting has taken a meaning that can now be applied to that history of Leonardo edition. In hindsight. In sum: Our flight of mind might start with a pen, but we get to, we live in the era of formatting. Of what, once, a pen, what once an intellect penned down on paper. Leonardo da Vinci’s intellect. Leonardo da Vinci’s pen.

(Source: »Carnet de Londres«, p. 33

[ms. 3], compare below)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen II –

Paul Valéry

Paul Valéry’s drawings of hands from the only recently published 1894 »Carnet de Londres« (source: »Carnet de Londres«, p. 33 [ms. 3])

One has raised the question why I have not discussed the Leonardo reception of Paul Valéry in my 2011 book on ›Leonardo’s Travels to the East‹ (Leonardo da Vinci im Orient. Geschichte eines europäischen Mythos), which is dedicated to the cultural history of a particular idea: the idea that Leonardo da Vinci had indeed, that is: physically travelled to the East. An idea born from the head of historic Leonardo, since it was Leonardo himself who penned down such a fancy of the mind in a first-person account, which, nonetheless, is not to be considered as recalling the historical reality of an actual journey (albeit the mere idea, as we will see, produced many a historical reality, not the least in the minds of other people).

In sum: Why not Valéry? Not because I would have ignored Valéry (as you can see in my book I have even used, as a motto of one chapter, a quote from his remarkable 1938 essay Orientem Versus); but because Valéry was not among those who, in their own mind, elaborated on the idea of ›Leonardo Orientem Versus‹. In other words: Valéry was among those – and this, perhaps, I might have said in my book, but I am saying it now – who decidedly made Leonardo a European mind. Considered him to be an embodiment of the European mind. And the question to be raised here might be if Valéry also did format Leonardo to be a European mind.

When beginning to write about Leonardo in 1894.

(Picture: goodreads.com)

The Carnet of the 1894 London stay of Paul Valéry has only recently been published. In 2005. And what is interesting, among many other things, is that this journal, dating from the very time when Paul Valéry was embarking on writing on Leonardo, also visually resembles the journals of Leonardo da Vinci. With, chaotically, or seemingly chaotically, assembling the most diverse ideas, from mathematical equations to architectural sketches. And also sketches of a hand, which – according to the edition’s commentary – seems to be the hand of Paul Valéry’s little cousin.

The edition of the journal, furthermore, does ressemble editions of the writings of Leonardo da Vinci, in that we see here a combination of transcription, commentary, and graphical reproductions of the actual pages. Not to forget an introduction, putting everything into context.

The question that remains, at least in my opinion, if this all is not, at the same time as this method to edit Valéry does produce order, this method does produce the same kind of suggestive magic that many editions of Leonardo do produce. Because, as systematically rational this all might appear, what we see, at the same time, produces associations of everything with everything. And this limitless relating everything with everything, art with science, science with art, can, by definition never be exhausted. Due to limitless possible relations. Everything mingles. Everything fuses, and what results is more of a sound than it may be called rational order. And a mind, attempting to understand, has to make sense (or it simply, if inclined more to mysticism, immerses into that sound of sense-production, with, as one might say, nonsense-production as the white noise within that sound), with making sense meaning here, probably, finding a meaningful path, if there is one, while proceeding through a landscape of limitless relations and associations, assonances and echoes.

Not to mention that, to understand Valéry, we would have to read and study what he read and studied then, in 1894. Because otherwise we would not be able to grasp what certain names might have meant to him then. Not to mention what persons, places, might have meant to him. Or architecture. Or the visual impression of a hand holding a pen. Or playing with a pen. (And the drawing on the right might, again, remind rather of a pen dancing, or a hand playing; while actually it is not merely a hand playing, but a mind dancing, inside, if one likes so, the very pen or: inside the movements of that very pen, prepared, or preparing to pen down – sense, and/or nonsense).

(Picture: amazon.com)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen III –

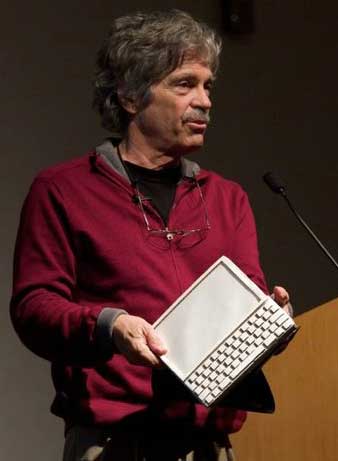

Steve Jobs

(Picture: biography.com)

Philippe Starck writes: »Can there be any doubt that Steve Jobs was a modern-day Renaissance man — a latter day da Vinci, brimming with creativity, invention, aesthetic and business acumen!«

(picture: wired.com)

»In fact some of the best people working on the original Mac were poets und musicians on the side«, Steve Jobs-biographer Walter Isaacson has Steve Jobs say. At the end of his Steve Jobs biography, allowing him to have the last word. – And the full passage is remarkable and deservers close reading (and a few comments).

But first of all: I am certainly not the first to wonder what a man with exactly the same mental and bodily dispositions like Leonardo da Vinci, under circumstances of today – what would such a man become? In our time?

And I believe that one can elaborate on this particular question in two ways. On the one hand one might think about what the analogy of what Leonardo da Vinci, at his day, did do – would be today (and one might imagine him working on the Venice MOSE project, or imagine him as the mastermind on the Titanic movie set, not only building every tank, every stage and every ship model, but every day coming up with new special effects, but also with ideas as to camera positions, the lighting, the script… the art works used as props… and so on; in sum: I am inclined to think a bit of Dante Ferretti here, but maybe, we should think of a whole one man film crew…).

On the other hand one might think about how a piccolo Leo, being born in 1952 (and not in 1452) would have developed, under modern circumstances.

Imagine him, for example, on a Vespa in the hills of Florence. And then wrangling with teachers and professors, not allowing him to remain a generalist and to develop interests in all directions. Because, as F. Scott Fitzgerald did write in his novel The Great Gatsby (Nick Carraway’s speaking) – you might be more succesful in life, if you do look at life only through one single window. But what window would that be (and ›window‹, as we sense right away, has a ringing, a slightly odd ringing here).

Poets and musicians on the side. Well then (but we should also keep in mind, that, perhaps, our time would not allow Leonardo da Vinci, to become anything, because as popular a rhetoric of transdisciplinarity might be, those who really embark on it, face nothing but trouble… and specialization is what seems to be more required; unless the one or other Renaissance woman or man will teach us, will teach the world otherwise…

Poets and musicians on the side. Let’s hear now what Steve Jobs once told his biographer Walter Isaacson, in full:

»Edwin Land of Polaroid talked about the intersection of the humanities and science. I like that intersection. There’s something magical about that place. There are a lot of people innovating, and that’s not the main distinction of my career. The reason Apple resonates with people is that there’s a deep current of humanity in our innovation. I think great artists and great engineers are similar, in that they both have a desire to express themselves. In fact some of the best people working on the original Mac were poets and musicians on the side. In the seventies computers became a way for people to express their creativity. Great artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were also great at science. Michelangelo knew a lot about how to quarry stone, not just how to be a sculptor.«

May this passage first resonate for a bit. And may one understand my comment that follows as a more relating it to what we have already said above, in sum, as a putting the passage into our context.

(Picture: museum-gestaltung.ch)

What strikes me, as someone who, while growing up, experienced Polaroids at family gatherings here and there, is that Steve Jobs’ train of thoughts starts with something that had, as I would recall it, also a little bit of theatrality ot it and was – if a Polaroid was taken – a social event. Something playful that had to be staged. And then one had to wait for the Polaroid, while the conversation went on, and then everybody could look, one after another, at the Polaroid having developed. Technology, or a technological tool, embedded in its social use, this is what I do recall. One had given people something to play with, as one might say as well.

Who gave, according to computer scientist (and also musician) Alan Kay,

an apt description of software?

Right. Let’s hear first what Kay said, and then we may turn to the source:

»Computers are to computing as instruments are to music. Software is the score,

whose interpretation amplifies our reach and lifts our spirit. Leonardo da Vinci

called music ›the shaping of the invisible‹, and his phrase is even more apt as a

description of software.«

The source of this dictum may be (perhaps indirectly quoted) the so-called Codex Urbinas

(not penned down by Leonardo da Vinci himself, but compiled by a pupil, and thus at the origin

of the so-called ›Book of Painting‹ tradition). We may quote here from Jean Paul Richter,

The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci (1939 edition), vol. 1, p. 80 [giving Urb. 18a-19a;

respectively Trat. 32]:

»For these reasons the poet ranks far below the painter in the representation of visible things,

and far below the musician in that of invisible things.«

(Picture: history-computer.com; Kay quote: http://iae-pedia.org/Alan_Kay#Alan_Kay_Quotations;

(Computer Software, [in:] Scientific American, September 1984))

And playing has not only the playful, but also the very serious side to it. And perhaps it is the Homo ludens we are talking about here. Who unites the interest, the passion for technology (let’s say here: for tools), with an awareness that we are playful animals, and above all: a playful side. Playful animals, producing and interpreting poetry and music – well, by playing. With words and sounds. With sense and meaning. And today also: with tools, playing with words and sounds, or helping him in any other, often completely unforeseen ways.

Having an awareness for both sides, this seems to be what Steve Jobs is talking about. Getting the most out of your equipment, and the precodition of getting the most out of it might be to have an awareness what you might want to do as an artist (even if you don’t yet know exactly, and that you will develop a more precise sense only while doing it), and to have an intuitive feel as to how your equipment might help you with that (perhaps also with, at the same time, limiting rigidly what you might do; perhaps also in limiting you by allowing you too much).

It is interesting that Steve Jobs does speak of science and the humanities first, and goes on to speak about ›humanity in the innovation‹. The German translation of the Steve Jobs-biography by Isaacson makes »etwas Geisteswissenschaftliches« out of the notion of ›humanity‹. I don’t know if this is really what Steve Jobs meant. Did in fact the Humanities contribute to the innovation, or is the innovation redolent of ways a user (here for example the poet, the musician) might think as a human Homo ludens (while the Humanities in fact are dedicated to the study of humans, having expressed themselves culturally). It seems to me that the translation does give the Humanities (the Geisteswissenschaften) too much credit. But anyway.

In the end Steve Jobs comes to mention Leonardo and Michelangelo, but, if I am not mistaken, rather humbly. Only bringing in, marginally (but substance might reveal in the marginally said) some analogy. Some examples of individuals who cared much for the technical side of artistic expression (and in that, but perhaps also in other ways were scientists and engineers), and at the same time were great artists. And it is striking that Steve Jobs seems to have regarded Leonardo and Michelangelo primarily as artists, that also were great at science. A hierarchy shines out (and not the classical vertical series: Leonardo as a painter/draftsman, scientist, engineer). And we again do recall: Some of the best people working on the original Mac were poets and musicians on the side.

In sum: let engineers and artists be sidemen (if the notion in its musical meaning may be allowed), have them play in the human band, with some of the players being musician’s musicians (knowing much about musical technique), others more intuitive players. But what all musicians have in common – and may this sentence be dedicated to my own Mac that just now allows me to type that very sentence – they care about their equipment (and we should also be humble, at times, as to our sidemen – and -women, like for example Adele Goldberg – in technology).

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen IV –

Rainer Maria Rilke

(Picture: literaturatlas.de)

(Picture: dreamstime.com)

Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, as far as I can see, never went as far, in his letters from various places to his many penfriends, to pretend that he was travelling to or in Eastern regions. But he went as far, once, as to imagine that he was going to learn Arabic, and to imagine that, possibly, we was going to publish his next books at Baghdad or Sarmarkand (letter to Nanny Wunderly-Volkart, 16 January 1923).

What penfriends Leonardo da Vinci had in mind, when penning down his notoriously famous (but little studied) letters from Eastern regions, first-person accounts, seeming eye witness accounts that made – at least some people, some Leonardo scholars – think that Leonardo da Vinci had actually travelled to Eastern regions and was writing from Eastern regions (see my above mentioned book), what penfriends Leonardo had in mind, in sum, we don’t know exactly. (But probably this letters were in the end directed either to himself, or to his pupils and friends, meant to entertain them, but perhaps also to teach them about geography and other things.

Rilke, which might come as a surprise, but indeed the affair about Leonardo’s alleged travels was, once, fairly well known (and has only later been forgotten), Rilke knew about Leonardo scholarship discussing, fabulating about the possibility of a real journey. To Eastern regions. And Rilke, as we know from one letter, enjoyed to further imagine that Leonardo had also travelled to Muslim Spain.

As a poet Rilke did not elaborate on that subject (as we will see another poet, Gunnar Ekelöf, was going to), but penning down a letter (or postcard), we see here, might be the appropriate medium to romance about things (without having to elaborate on things). And why should Leonardo’s curiosity have accepted mental, intellectual or geographic borders?

His pen, his mind, at least, did cross such borders. By having Leonardo himself imagining that he had left Europe and was writing from Eastern regions. Not to European penfriends, by the way, but to an Eastern superior, to an Egyptian superior to be precise, to whom he had to report.

Cy Twombly: […]. There's a linguistic thing that crops up regularly.

Like the paintings in London. There's a kind of garbled form of Japanese writing, pseudo…

Nicholas Serota: Pseudo?

CT: Yes, pseudo-writing. And the Salalah paintings [above: Note I from III Notes From Salalah]

are a take-off on arabic. That's why I named them that way, I tried to put it in a desert. I mean, the writing

and certain garbled linguistic things…

(Source: Nicholas Serota 2007 interview with Cy Twombly; picture: wikiart.org)

What Rilke imagined was, among other things, that Leonardo might have been fascinated by Muslim art, by ›speaking walls‹, by bridges, by ornament and scripture. And what is interesting here is that, while we are used to accept that Leonardo did cross intellectual borders all the time, at least in the field of science and engineering, a mental barrier in us might find it rather odd that someone we are used to see as an embodiment of European science and Western scientific curiosity, that such a person would have crossed cultural barriers. Barriers that have to do with language and scripture, with cultural values, and, yes, also with religion, interacting with cultural values.

But why calling Leonardo a ›universal genius‹ then, if he in fact was, culturally, rather disinterested.

The historic Leonardo, was not culturally disinterested, but his interest certainly did not cross every border and every barrier one might imagine a ›universal genius‹ might have been able to cross.

But his mind did, occasionally, even if some scholars or European audiences, or Western audiences find it difficult to accept (or on the contrary: get all to enthusiastic about it), and, yes, his pen did.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen V –

Bill Gates

(Picture: media.techeblog.com)

Bill Gates contemplating something that also could be described as one ›relic‹ of the Leonardo myth – the Codex Leicester (picture: youtube.com; 60 Minutes)

›Turbulence‹ is a magic word. Leonardo da Vinci attempted to understand turbulence. Which we do know because we have the Codex Leicester, owned by Bill Gates (who acquired it in 1994). And ›turbulence‹ is also a nice example for what one may call the two sides of the Leonardo myth: one side, one might say, has to do with what Leonardo actually did achieve. As an artist, painter, engineer, scientist and so on. How far he actually got with theorizing and with understanding turbulence is up to few specialists to explain. But this is only the one side.

Because at the same time Leonardo can also be seen as one embodiment of curiosity. This side of the Leonardo myth is about symbolizing (all-sided) curiosity. And it actually does not really matter how far he got with understanding turbulence. It is about scientific curiosity as such. About being interested in things, in nature, in the nature of things. In turbulence, for example. For any reasons. For practical reasons, or simply because it is a human thing: to seek knowledge, to have a better understanding of the world, and also: to be able to do practical things, on the basis of the knowledge found, and thus a deeper understanding of the world, not to mention a perspective to become active. By shaping things, cultural things, and perhaps even the nature of things.

Bill Gates certainly has been asked innumerable times why he did, in 1994, acquire the Codex Leicester, which deals with geophysics and above all with water. One time, when asked, he apparently simply said enigmatically ›because I wanted it‹ (and this reminds a bit of Leonardo scholars who, if asked some questions, simply answer with ›yes‹ to everything they get asked; which perhaps rather often translates into ›yes, yes, leave me alone‹). On other occasions Gates named several reasons, and yes, why should it be at all about the one single reason only?

I do believe it is one thing to know about Gates’ personal motifs (and for Leonardo scholars it would be also interesting to know if Bill Gates, when being nine, ten years old, took notice of the rediscovery of the Codices Madrid in 1964ff.).

But it is another thing to think about what Bill Gates actually did achieve with acquiring the Codex Leicester. And I believe that he did achieve something rather unique, and something that might have only indirectly to do with his private motifs, and still it is something that only Bill Gates was able to achieve. In brief: Bill Gates, in acquiring the Codex Leicester, provided no less than an update to the Leonardo myth. The narrative of Leonardo achieving things on the one hand, and seeking for knowledge on the other, is now associated with everything that Bill Gates, as a symbolic figure, does represent. And this no other person than Bill Gates was able to achieve. And the metaphor of ›update‹ is the very term to describe, on a level of cultural history, what happened.

(Picture: seattlepi.com)

If we think back of the time of Paul Valéry, it was aviation updating the Leonardo myth. Aviation advanced at the very time international scholarship also embarked to work on the Leonardo codices, including those dealing with flying machines, the birdman etc. And one did look back at the time of Leonardo, at the Renaissance, from the time of aviation. And perhaps the age of aviation also found inspiration in Leonardo. But the Leonardo myth, at the same time, was also invigorated by aviation literally taking off. Without someone actively updating the Leonardo myth (because it was obvious that Leonardo had thought about flying machines and had dreamt of what mankind was now able to achieve).

Now with Bill Gates, the age of the computer, the internet and of digitization (the internet of things upcoming) is looking back at Leonardo and at the Renaissance. And Leonardo does now appear as still being of importance as a symbolical figure, as someone who achieved things, or as someone who symbolized scientific curiosity, in the age of digitization. And as someone, as Gates also did say publicly, being ahead of his time. As a solitary visionary. And here the private story, the biography of Bill Gates probably intertwines with the history of the Leonardo myth. Because here perhaps also very private motifs and memories come in: starting to do visionary things all by onself, or with few others. Without getting much feedback (because who would be able to provide a visionary with feedback?) Specialization turned out to be all-relevant. And the former specialist turned out to be an all-interested person.

In August 1919 the Leonardo myth was ›updated‹

by an issue of the Daimler Werkzeitung being dedicated

to the universal genius (picture: daimler.com)

And we would like to leave it here with showing a picture of Bill Gates contemplating the Codex Leicester (or contemplating ›a window‹). Perhaps musing about turbulence. But perhaps also paying respect to a man, to a myth, representing scientific curiosity as such (and indirectly to his pen, his most important tool, without it we would not know of Leonardo aspiring for knowledge at all).

And the picture, perhaps, does also speak for itself in another sense. Because it is still one thing to know about Leonardo representing scientific curiosity; and it is another thing to be in the presence of this myth (due to a ›relic‹).

That works, as a myth, as one of the primal and all spread narratives as regards scientific knowledge. And it has worked so now for quite some time. And it goes on to work so, now also due to Bill Gates having provided the myth (read: an all-known narrative expressive of essentials of human life; we do not thing of myth here in terms of something being questionable or untrue) with an update. Without it being of importance if Leonardo actually achieved something that relates to the age of the computer. But with being of importance that, 500 years ago, someone, perhaps as a solitary explorer (or with few others), was trying to understand something like turbulence. And used, as the tool of his visual musing and his thinking, a simple pen.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen VI –

Gunnar Ekelöf

(Source: Gunnar Ekelöf, Führer in die Unterwelt, Münster 1995)

If Swedish poet Gunnar Ekelöf (1907-1968) had been a filmmaker and not a poet, German critic Peter Hamm has written, he would have been as prominent as Ingmar Bergman. And indeed, and as surprising it may sound, Ekelöf’s ›Guide to the Underworld‹ of 1967 (Vägvisare till underjorden) – why not thinking of it it as a kind of inner screenplay. That could be set in motion pictures, for example by as visionary a filmmaker as Werner Herzog. Since this ›guide‹, that draws on many traditions (Homer and Dante, very in particular, but also on Ekelöf’s own real and mental travels), could also be named a visionary inner journey, with certainly a particularly rich imagery.

That draws, among other things, on ›armchair traveller‹ Leonardo da Vinci, having penned down his above mentioned letters to an ficticious Egyptian superior. Letters sent, allegedly, to that superior from Eastern regions.

And with this, as one may say, we do see the analogy in poetry, the analogy to Bill Gates updating the Leonardo myth (as far as the myth does speak of the visionary scientist and of scientific curiosity): since Ekelöf, who was not interested in Leonardo, the scientist, at all, adapted Leonardo’s literary doings and particularly his literary visions, expressed in ficticious travel writings, for and in the context of modern, of 20th century poetry. And this after poets like Baudelaire and other 19th century writers had already frequently been concerned with Leonardo, but more with his painterly work, with his paintbrush, and not with the cosmos of his notes and notebooks, journals, in one word: with his texts (that often are, however, scattered with writings, and present any editor with great difficulties). Or with his pen.

›If you prize liberty do not reveal that my face is the prison of love‹ –

this isolated note by Leonardo (Codex Forster III, 10b; translation of Carlo Pedretti)

also the German art historian Horst Bredekamp used,

namely as the motto (or starting point) of his 2010 book Theorie des Bildakts (see p. 17ff.).

Pedretti notes also (in his 1977 commentary to Richter, Literary Works, vol. 2, p. 313,

and perhaps aware of Ekelöfs use of the note within the context of his poetry as seen above)

that the original Italian words can be transcribed into two hendecasyllables:

Non iscoprir se libertà t’è cara

che ’l volto mio è carciere d’amore.

(picture: faz.net; Bredekamp has the note as »Nicht enthüllen, wenn dir die Freiheit lieb ist,

denn mein Antlitz ist Kerker der Liebe.«)

And Ekelöf can not only be seen as the one modern poet (after Valéry and Rilke) being concerned with Leonardo’s pen, but as the one poet (after Rilke had also been interested in Leonardo as a traveler) who took Leonardo’s (ficticious) travel writings very seriously. But seriously not as a scholar, but as a poet.

Resulting with this writings by Leonardo appearing within the Ekelöf cosmos as sources that rank next to Homer and Dante, as far as the ›Guide to the Underworld‹ is dealing with travelling. Mental travelling. But also real travelling, and with the travel account, oscillating between the real and the imaginary. Since Ekelöf, in his own notes, does also express a certain reserve to designate Leonardo’s accounts as being purely ficticious (and one does sense that Ekelöf would also have liked the idea of Leonardo having been a traveller, physically exploring the East). Showing fascinated, like many readers and writers before him, in the mysterious ambiguity of writings that – seemingly – speak about real things. As if real things had actually had been seen. In the East. By Leonardo.

We are not going to explore the Ekelöf cosmos here (the ›Guide‹ is to be seen as the middle section of an actual trilogy), but leave it with a few remarks.

First of all what fascinated Ekelöf as a writer were apparently two things: Leonardo’s mirror writing, on the one hand, which, in a motto, he even formally adapted – if not in plain mirror writing, but in terms of reverse writing (see above).

And on the other hand, and very in particular, the motiv of Leonardo travelling to the East, which of course, can also be interpreted as a representative of the West (or even the representative) exploring the East, conversing with the East and everything that may (in European eyes) be associated with the East. And thus both motives have to do with the motif of the mirror. In writing, on the one hand, and in a more general sense, as far as cultures perceive (or mirror) each other (not without respective distortions), and as far such encounters are staged, imagined, or set. By whatever side.

It deserves mentioning that Ekelöf’s biography does show the son of a banker exploring, in his own way, East and West (Ekelöf studied oriental writers and languages), and that he adapted Leonardo certainly as a persona to speak for him and also of own experiences, visions and thoughts.

But in the end we see, and this is what does concern us here, that Leonardo’s writings are indeed a deep well. Since computer scientists may find stimuli to their own intellectual adventures (in hard- or software). But writers, people concerned with texts (or also with texts, but in another way), find stimu.i as to their respective endeavors. And this may result from Leonardo’s genius, but it does certainly also result from the mysterious aura by which Leonardo’s writings are surrounded, and from the ways these writings are formatted, organized, edited, commented and published.

And what we may learn, among other things, from being concerned with Ekelöf, may be that not only clear sense, resulting from Leonardo’s insights, might be of interest. But also the very aura of mystery, produced by scattered, fragmentary, mysterious notes and remarks (not necessarily intended by Leonardo). Notes and remarks that are not only of interest, because they may stimulate a seeking for scientific or philosophical truth. But just because they stimulate, in their often cryptic quality, the searching inner mind that already has embarked on a journey of whatever kind. And thus these notes may stimulate poets and mystics. And poets like Ekelöf, that also could be named a modern poet and a mystic.

| Codex Atlanticus 393v [ex 145v-a; v-b] (picture: PeopleOfAr) |

|---|

|

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen VII –

The Inventurer

(Picture: welt.de)

(Picture: comicvine.com)

Inventurers get a lot of requests for making inventions (the swarm is in some sense pre-inventing, or inventing with them), and if they say no, it does not necessarily mean no, but rather: no, no, leave me alone.

And I happen to know this because I am (a mighty venture capitalist) in the posession of an unknown Leonardo codex. Which deals exclusively with the problem of how the Egyptian pyramids were once constructed.

This is of course a classic problem to study, and without any doubt this codex is authentic, and Leonardo did in fact spent many hours to reflect on how the pyramids were built (and on how they could have been builded with no unhuman working conditions for workers etc.). In sum: in his typical way of visual musing about such things, Leonardo seems to have drawn nothing else but large trolleys. And as we know the trolley is thought to be a glorious 20th century or so invention, but this seems not to be the full truth. Since Leonardo, at his day, already had thought about giant size trolleys, and about giant sized automats (we’ll think about the history of the robot another time), well, building the pyramids. The drawings are mightily impressive (perhaps I’ll post them another time).

For those still thinking that Leonardo actually did spent time in Eastern regions physically, this might come as an disappointment, but there is no proof that Leonardo ever left his Italian study. Building the pyramids in his mind by nothing but thinking and visual musing, and without leaving, at any given date, his study. Nothing else but Leonardo with a pen (and paper).

The history of the trolley, by the way, seems to be much neglected. Which is the only reason that we did post this here (as another, and as the final contribution to Leonardo’s Pen).

From: Microstory of Art V –

Leonardo da Vinci

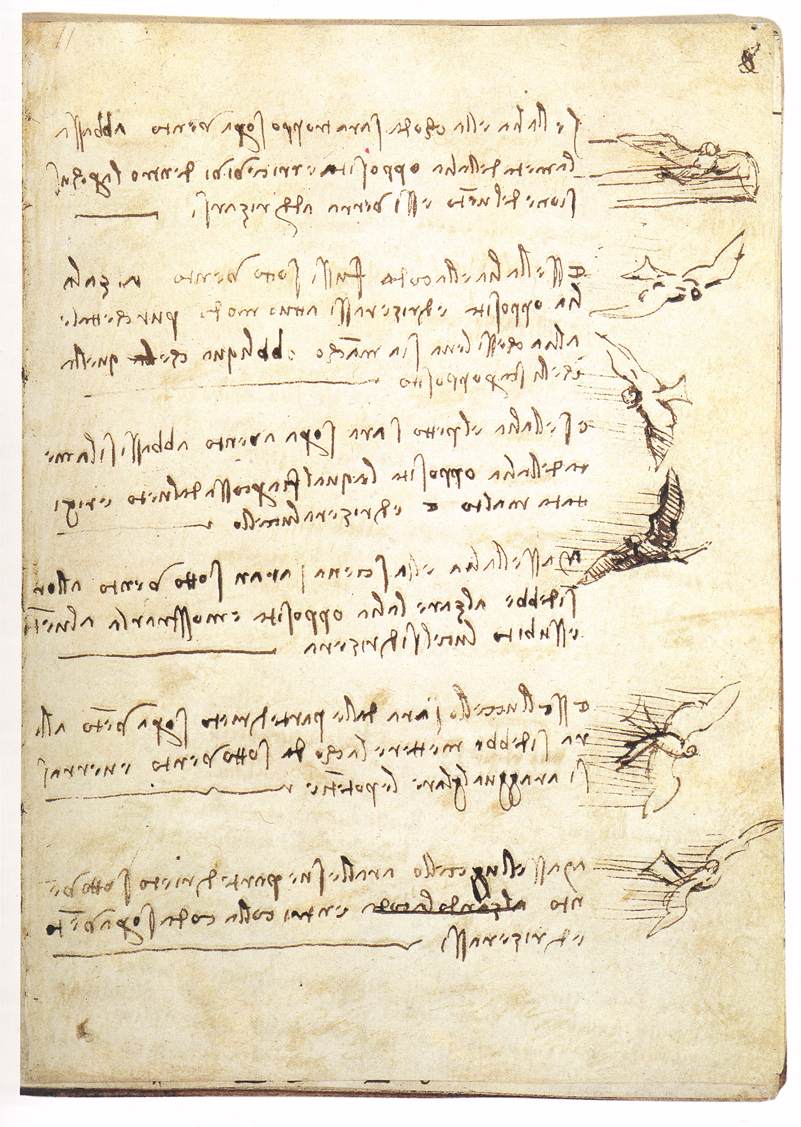

Pseudo-writing by Leonardo

| Manuscript B 100v (with, among other things, Leonardo’s bat) |

|---|

|

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen VIII –

Aviation

(Picture: flyingmachines.org)

A bird’s wing, or also a little taste of bat? In any case Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing introducing this history of aviation (source: Kurt W. Streit/John W. R. Taylor, Die Geschichte der Luftfahrt, p. 9)

A general consensus under scrutiny. What consensus? – The consensus that Leonardo was only a forerunner of the 19th century pioneers of aviation. Otto Lilienthal, the Brothers Wright, Clément Ader and so on.

The emphasis, here, lies on ›only a forerunner‹. Because what if Leonardo, due to his notes becoming known at the end of the 19th century, would also have had an impact on these pioneers?

The question, it does seem, has never really been studied in earnest. And although we actually do rather not believe that Leonardo had an actual impact on the history of aviation, we would like to show how one might check if he had.

(Source: Otto Lilienthal, Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst.

Ein Beitrag zur Systematik der Flugtechnik, Berlin 1889, p. 89;

deutschestextarchiv.de; see also p. 90 with reference to the bat)

One has to know that snippets of Leonardo’s notes on flying machines, the flight of birds etc., have not become known only in 1893, when the Codex on the Flight of Birds was edited for the very first time as a whole. We have to mention that already Jean Paul Richter, in 1883, edited, within his monumental two-volume anthology, notes by Leonardo dealing with the flight of birds.

Another bat in Leonardo (source: leonardodigitale.com)

And here we face an ideal example of what it does mean to be confronted with a ›Leonardo formatted‹.

Because Richter chose notes, from Leonardo’s notes, to be published. And arranged these notes according to the principle of subject matter. Paragraphs No. 1122-1126 thus are assembled under the header »On flying-machines«, and whoever did read these notes, in 1883ff., was confronted by the remarkable fact that Leonardo, while studying the flight of birds, felt intrigued to, well, study also, and particularly the bat.

»Remember that your flying-machine must imitate no other than the bat, because the membranes serve as framework«, we do read in paragraph No. 1123. And with another note Leonardo da Vinci reminds us, well, does recommend to us, to also dissect the bat (No. 1123A), and to construct our flying machine »on this model«.

On our part, we do recommend now to all experts on the history of aviation, to think about if any of the 19th century pioneers in aviation might have been intrigued to do exactly this: turning to the bat (while or after studying the flight of birds). And this, perhaps, inspired by/due to Leonardo turning to the bat. Or more specifically: turning from the study of the flight of birds to the wings of the bat.

And we may conclude here, although we still stick to the hypothesis that Leonardo (or ›formatted Leonardo‹, another interesting possibility) did not actually influence the 19th century pioneers in aviation, we still may conclude here, that for example in Otto Lilienthal, that is: in 1889, we do find another bat. A bat, not exactly as we do find in Leonardo. But still a bat, within a book on the flight of birds. A bat like in Leonardo, as we might say at least, noticing two histories seemingly intertwining (but here we do stress, for matters of precaution, the ›seemingly‹).

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen IX –

Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder

(Picture: zeno.org)

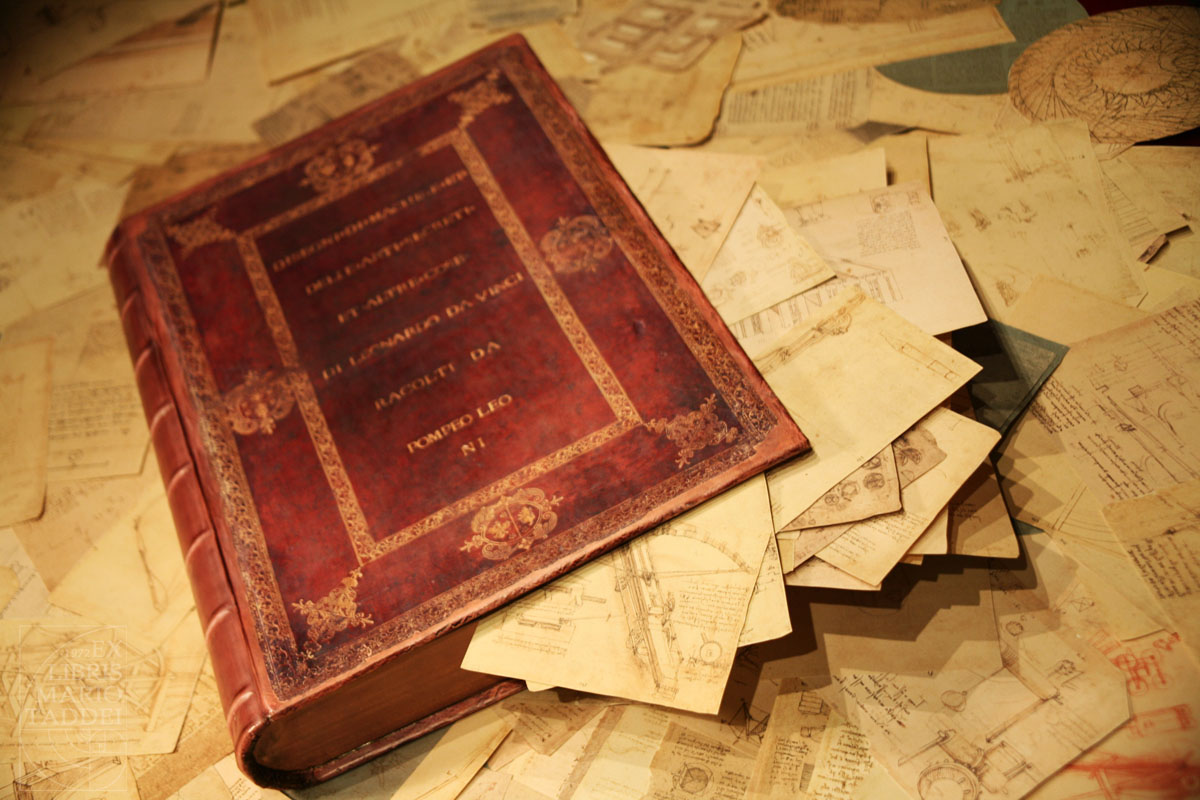

(Picture: Mario Taddei)

Romantic poet Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder had an excellent sense for where to dig. Only that he did not dig himself.

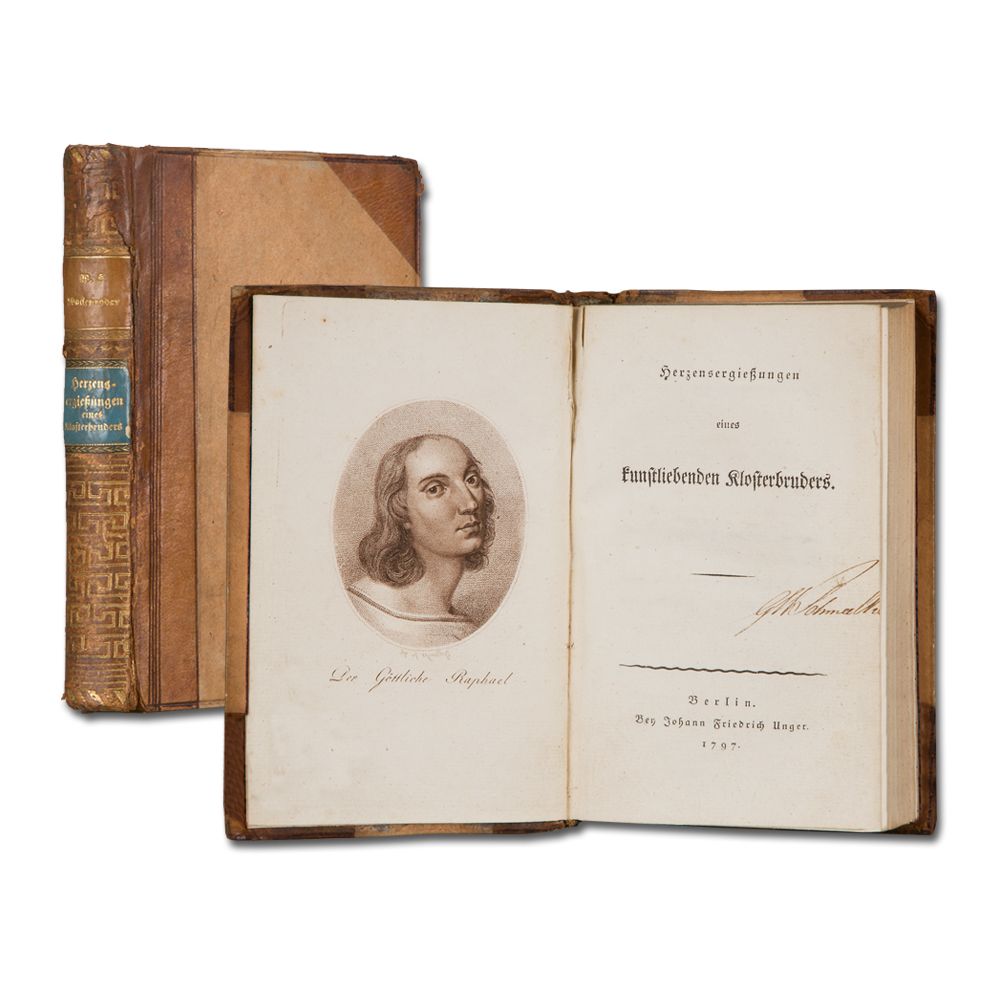

The whole history of Leonardo reception that has unfolded here, virtually began after Wackenroder, in cooperation with Ludwig Tieck, published the 1796 Herzergiessungen eines kunstliebenden Klosterbruders, a classic of Romantic literature, a classic of German literature of the Romantic era.

»Während des Aufenthaltes in seiner ländlichen Einsamkeit trug er [Leonardo] nun auch

die Resultate seines Studiums, durch seinen Geist gesteigert und geläutert,

und mit seinen eigenen sehr scharfsinnigen Gedanken und Beobachtungen versetzt,

in ausführlichen Werken zusammen, welche sich, von seiner eigenen teuren Hand geschrieben,

noch itzt in dem großen Ambrosianischen Bücherschatze zu Mailand befinden.

Aber ach! es ist auch diese, wie so manche andre uralte, mit ehrwürdigem Staube bedeckte

Handschrift in den Bücherschätzen der Großen, ein unangerührtes Heiligtum, vor welchem die

unverständigen Söhne unsers Zeitalters, höchstens mit einer leeren Ehrfurchtsbezeugung,

vorübergehen. Das Manuskript wartet noch auf denjenigen, welcher den Geist des alten Malers,

der darin verzaubert schläft, daraus erwecken, und aus den lange getragenen Banden erlösen soll.«

(Source: gutenberg.spiegel.de; picture: antiquariat-voerster.de)

And this does not mean that this history did begin due to this classic. No, what unfolded did not unfold due to Wackenroder/Tieck. But still what Wackenroder did, in 1796, was pointing to a source. To the Codex Atlanticus, kept, as he knew, by the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. And the Codex Atlanticus might also be seen as a symbol, as a pars pro toto, a large pars for what might be called the whole of the extant ›notes with drawings‹ or ›drawings with notes‹ by Leonardo.

Wackenroder had, obviously, no exact notion of how

the Codex Atlanticus – not at all a book as we would understand it,

but a collection of sheets – looked like. But Wackenroder obviously

had a sense of what might be hidden in large quantities of

Leonardo’s notes: manifestations of his mind, elaborated by his pen,

elaborated by writing, while writing, while drawing, before and after

writing and drawing, while thinking, and before and after thinking…

a sanctuary, as Wackenroder says? Perhaps… but untouched no longer.

And sleeping, enchanted, and waiting, as an enchanted mind,

for someone to call him up…? (picture: incomingpartners.it)

And we have to quote what Wackenroder said. And see what Wackenroder said, against the backdrop of what came afterwards. A history of Leonardo inspiring generations of creative people, not only by his paintbrush, but by his pen.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Leonardo’s Pen

Leonardo’s Pen X –

Branding

(Picture: da-vinci-igs.de)

(Picture: the guardian.com)

It can be used as a brand. And what we mean is: Leonardo da Vinci’s handwriting can be and has been used as a brand.

Which means: the script, the mere visual quality of script, without us understanding what Leonardo is writing. Without contemplating sense. More exactly: without considering the exact sense of the words and phrases. Since there is sense. But sense on another level: on the level that we know that we do see writing by Leonardo (and here the drawings do help), writing that, like math, we do necessarily have to understand.

I know that because in our city we once had a Café Leonardo. Which had been decorated by enlarged excerpts of notes by Leonardo. That, of course, no one did read or understand. But clearly could be identified as something made by Leonardo’s hand and pen…

And this I would call a brand. A type of handwriting (mirror writing, of course) as a brand. A pen as a brand (speaking, here, metaphorically).

The Café, unfortunately, does no longer exist. But I am dedicating this last section of our now ten-part exhibition on Leonardo’s pen to the Café Leonardo that has vanished into history. Perhaps to one day, or right now, to be called up again. Not as a pioneer perhaps, of using Leonardiana as a brand, but as an example of how script can turn to be a brand, as a manifestation (as Wackenroder did know) of genius, as an intriguing manifestation a creative mind, and thus: of creativity (embodied by Leonardo).

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

For Leonardo speaking on pen and penknife,

on paper and ink, see Richter, Literary Works, vol. II, p. 310

THE LEONARDO DA VINCI

ARCHIPELAGO

HOME

(Picture: acmestudio.com)

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS