M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Abstract: The paper, in that it combines a historically informed perspective with some classification theory, offers a more radical critique of any working with properties than it is common in the context of attributional studies. It discusses the notion of the unique property, compares it to other notions (the characteristic property; the single likeness), suggests an indicator of quality for attributional studies to counter the ubiquitous problem of confirmation bias, particularly, but not only in the field of Leonardo studies, and offers a number of aids and tools to help catalyzing a more reflective working with properties on any level, stylistic, historical and material. Which is a condition sine qua non with regard to a general implementing of scientific standards and a rebuilding of scientific connoisseurship. With such rebuilding fostering a shift from anachronistic ›authory of the expert‹ towards an ›authority of the valid argument‹ and an ethos of transparence and verifiability as to the classification of any object.

The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship and the School of Leonardo da Vinci

Dietrich Seybold

1) Unique Properties Then and Today

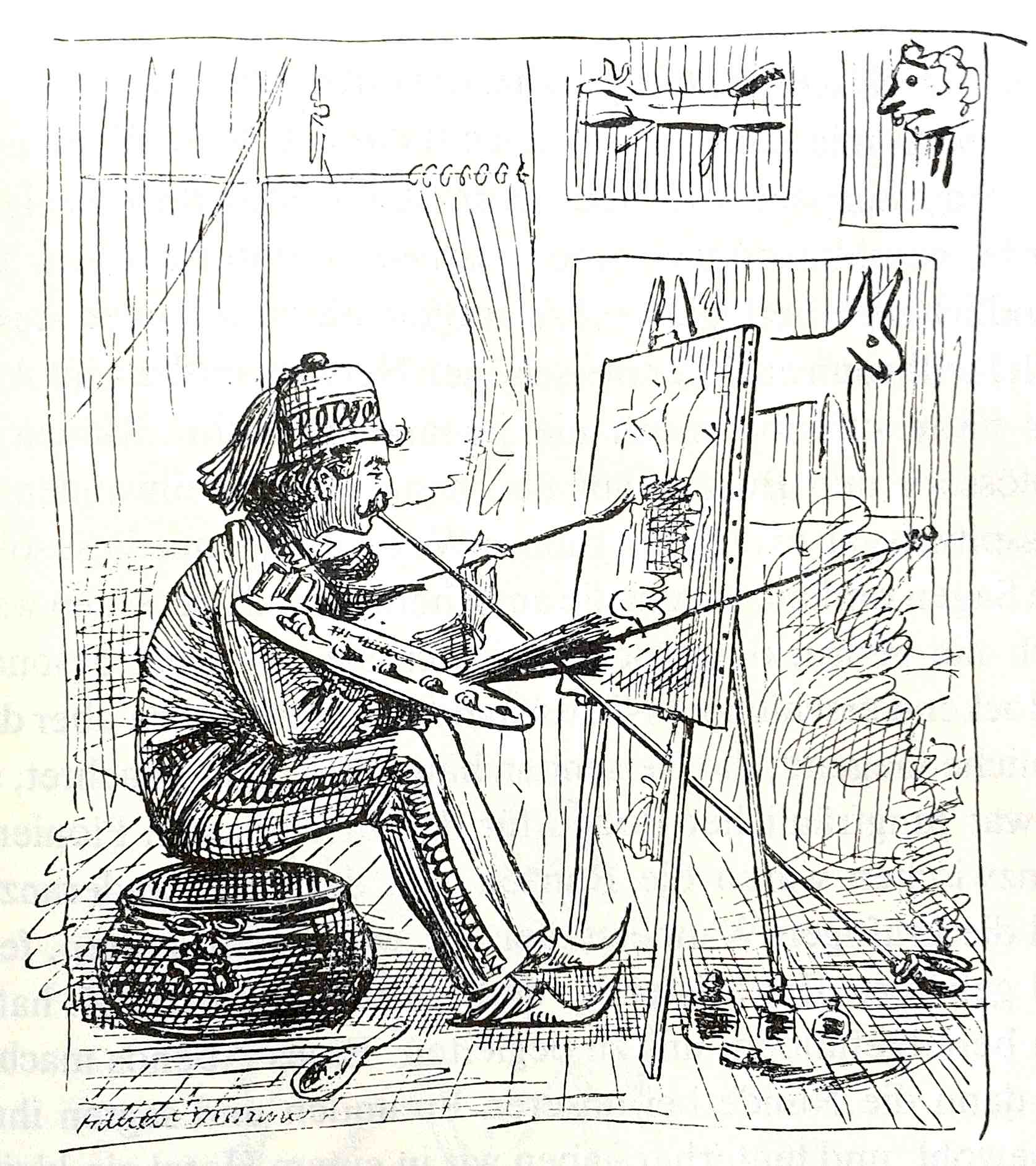

Perhaps surprisingly, it was the American writer Mark Twain who left us a viable definition of what is a unique property in the context of art. In his 1880 book A Tramp Abroad Twain has a hero and narrator travelling to Europe; and this ›tramp‹ shows also anxious to learn.

At Heidelberg summer days are passed, and satisfied about what he has accomplished the tramp indeed does show. Not only has he attempted to master the fearfully difficult German language to some degree, in fact one has also instructed the tramp to paint.

His teachers in painting do commend him for what he has accomplished, and this commending the tramp passes to us:

»They said there was a marked individuality about my style, insomuch that if I ever painted the commonest type of a dog, I should be sure to throw a something into the aspect of that dog which would keep him from being mistaken for the creation of any other artist.« (Twain 1880, vol. 1, p. 88)

And the hero and narrator continues to say (p. 89):

»Secretly I wanted to believe all these kind sayings, but I could not; I was afraid that my masters’ partiality for me, and pride in me, biased their judgment.«

And the tramp shows to be right, although at first he seems to be mistaken, since his teachers immediately and correctly attribute his painting, his first oil painting Heidelberg Castle Illuminated, that he anonymously does exhibit as a test, to him. But, alas, by passing strangers, the painting is taken as a ›Turner‹.

We can take two things with us from this classic of humoristic literature: first of all a definition of the unique property that yet is lacking a certain philosophical rigidity; a rigidity that however easily can be added: a unique property would be »a something« that with necessity would make us attribute a work of art to a certain author. Due to »a something« that we solely and exclusively do find in that particular painters’s oeuvre. In more abstract terms: in that one particular class of objects alone (compare also John H. Brown 2008, No. 1).

We would be kept from placing that object, mistakenly, into another class of objects, taking it for the creation of someone else. And that one property, that »something« would – even isolatedly – be sufficient to justify that attribution. ›Sufficient‹ would be the very term any philosopher would wait for, and characteristically, as we will see further below, one does rather tend to avoid that very term in the context of connoisseurship, while in Twain’s definition it is certainly lacking, but is hardly ›avoided‹.

But the other thing that we might take with us from the passage would be a kind of a warning: to beware of any (partial, biased) rhetoric of attribution, and all the more if such rhetoric would be redolent of a rhetoric of absolutes. Since, at least as it does show here on a level of fictional literature, that such rhetoric immediately might get deconstructed.

And this warning has another and very serious implication: the finding (identifying, thinking or even: constructing) of the unique property that with necessity places an object into one particular class of objects does go along with a heavyweight responsibility by which anyone is burded who is handling this type of property. Since the ambition is not less than to place a particular object into one particular class of objects (or also: into a most specific historical situation or location) beyond reasonable doubt. Or even with the boldness of absolute certainty.

But at least on a level of theory – this is what we would be allowed to do. If indeed we can handle unique properties. Which means here: if such properties in fact do exist, be it on a level of material qualities, physical or chemical (or biological), or on a level of stylistic qualities (intellectual aspects of style, that is: of form as a carrier of meaning, included); if we can know of them, detect them, and verifiably indicate them to others. In that case we would deal, justifiably, with absolutes.

It might just be one step from a disposing of the ultimate, i.e. ultimately reliable argument to being ridiculed as a charlatan for solely wanting to impress and to intimidate, but this danger has not prevented connoisseurs of the past from imagining of, and also of working with allegedly unique properties. Since also the lure has been the greatest possible one: absolute certainty, and also the efficiency of being able to make quick decisions, since one would be allowed to dismiss all other, seemingly less efficient approaches and tests for authenticity.

And towards the goal of absolute certainty all attributional methods do strive for. Even if it might turn out that only steps towards that goal might be possible, and the goal itself, the actual disposing of absolutely exclusive properties might turn out to be just an illusion. As a unicorn type of property. Rarely seen but constantly thought of.

As a guiding principle, however, the idea does at any rate exist, be it that what we at best do find, might be relatively exclusive properties.

Unique Properties in Leonardo?

Our discussion here is motivated by an interest in Leonardo, but the problems discussed are so basic that we face also a paradigmatical discussion that takes Leonardo da Vinci just as the most prominent, perhaps the the most radical example. The insights possibly gained might deliberately be transferred to other fields:

We face the problem to deal with a mythology as well as with an abstract intellectual problem. The mythology, in some ways, is part of the intellectual problem, since possessing a work by Leonardo da Vinci does mean to be in the presence of the relic of this particular mythology. And the urge to possess an object made by Leonardo da Vinci, very often, results in a equally strong confirmation bias as to the attributing of object to Leonardo himself. All informations indicative of not-disposing of a genuine Leonardo tend to be oppressed (and people do defend their self-deceptions unswerwingly); as soon as it does turn out that an object can hardly have been made by Leonardo himself, the interest shown towards such objects does rapidly dimish: it then turns out that the interest in the attributional problem is not particularly urgent. We should be warned, in sum, of an extreme amount of confirmation bias that might also be a core problem anywhere in authentication studies. Rarely discussed but – a problem of epidemic proportions.

But facing the problem might mean also to be able to counter the problem. And a first step might be, as one may say, to ›harvest‹ insights, about how confirmation bias does originate at the most basic level of things: at the working (and also: at the not-working) with properties.

It might be the fact that Leonardo da Vinci, traditionally, is considered to be an embodiment of genius, an ultimate genius, that, favorably, allows us to discuss, to construct unique properties on all possible levels here. One might even say, if properties are to be identified in Leonardo that they would to be considered as unique properties per se, since Leonardo is considered as to be unique per se. But such preconceptions (that would exclude for example accidental properties), as any short glance into the history of the Leonardo da Vinci oeuvre catalogue does show, do not exactly help us to deal with the cluster phenomenon in style named here as the ›school of Leonardo‹, which – deliberately – we do not specify as ›workshop‹, ›circle‹ or ›reception phenomena‹ here (for various conceptualizations see for example Caroli (ed.) 2000). Since it is just about that fuzzy cluster, about the problem of intimately related styles per se, about objects having passed from one subcategory into another many times and back. And about how methodological rigidity, conscient of the problem of confirmation bias, might deal with that intellectual problem in the future. With a problem which paradoxically, in its core, is about absolute uniqueness and absolute ambiguity at the same time, just since uniqueness has triggered manyfolded reception that resulted in the particular stylistic cluster phenomena leonardismo.

What might now be unique in Leonardo, what unique properties might we name (aware of the fact that all of such properties also have been projected into objects of minor artistic value, or yet even into works of shocking nullity)?

We might name (indicating rather some classes in broad strokes than single specific properties):

– properties resulting from a uniquely obsessive observation of nature (which can only be seen by individuals who share a similar knowledge of nature);

– material qualities resulting from obsessive experimenting with materials, mixtures, recipes etc. (of which we partly do know on grounds of the labyrinthine codices left by Leonardo);

– intellectual (for example theological) qualities resulting from having to deal with given problems in distinctive historical situations (commissions), with Leonardo solving given problems of representation in an unique way;

– qualities resulting from a unique facility of drawing and superb (or superior) painterly skills, creating a unique liveliness or ›presence‹, resulting in a unique misterioso or particular ambiguous atmosphere, and last but not least: beauty etc. (perhaps we may also think of painterly mannerisms on a level of technique);

– properties expressive of a uniquely deep understanding of human nature, character or soul (compare his theory of the portrait);

– and last but not least: perhaps we may think of unique marginal details on a level of style whose existence at least one foundational figure in the history of connoisseurship seemed to have postulated); and this is about the individual ›imprint‹ an individual might leave upon the representation of things (due to an individual processing of the represented during representation, resulting in what we call ›style‹), be it upon an anatomical shape in humans and animals (we recall the ›commonest type of a dog, rendered by marked stylistic individuality‹), landscape, botany, fashion, architecture etc., not because that individual knows, as an observer, more about such phenomena than other individuals, but since that individual, as any other independent mind, has incorporated peculiar individual notions of form that routinely find expression without the individual much reflecting about that ›leaving an imprint upon form‹ or about having ›an individually marked style‹ in everything (in Leonardo the problem is delicate since the style obviously also aims at a naturalistic illusionism, and ›correctness of representation‹ is not rarely seen as being characteristic as well).

Perhaps surprising, we do not spare or hesitate at all to speak of quality or beauty, even more so as the rhetoric of quality and beauty is probably the field of the most suggestive and intimidating rhetoric of attribution that indeed does expect – allegedly since words are lacking – that one does hesitate or stop to question the speaking and the spoken about. But from the perspective of scientific connoisseurship it is foremost about guaranteeing intersubjectivity of mutual communication, and if one human has declared what exact quality makes him or her weep, the scientific community is ready to discuss if that something, that particular quality is to be found in the object at hand, even if this very particular quality might make another human laugh (compare also John H. Brown 2008, No. 32 and No. 37) for the issue of intersubjectivity). Often heard may be the argument that ›it‹ could not be put in words. But the counterargument – in form of rhetorical question – goes: why having such a low opinion about what language can do (compare Perrig 1976, p. 89, note 5)?

Did Morelli postulate the existence of unique properties?

Mark Twain has been a contemporary of the one art connoisseur, namely Giovanni Morelli, who seemed to have postulated the existence of unique properties. They probably never met in person (although Twain crosses the Lake Como region), but shared a very similar sense of waggish humor, and it would indeed be worth clarifying, if the writer’s humoristic approach to attributional studies was not directly or indirectly informed by what was going on at the day inside the culture of connoisseurship.

At least the writer’s position was redolent of the positivistic zeitgeist, since at the very time connoisseurs of art were tackling with what Giovanni Morelli actually had meant with his recommendation to work with particular stylistic properties that the art historical tradition tends to name as ›Morellian properties‹ (compare the definition given above in terms of an ›imprint upon form‹). The question has remained, and as a matter of fact, up to the present day, tradition has rather avoided to raise the question: What indeed are Morellian properties at all? Is it about what has been named unique property here, about the ultimate lure, the ultimate certainty? And if not so, about what it is?

At least the German art historian Anton Springer had attempted, in reinterpreting what Morelli had said in his writings, to clarify what Morelli had meant (and this in 1881, only one year after Mark Twain had published the Tramp abroad). And the way Springer interpreted Morelli (see Springer [1881]) was unambiguous, in that it was indeed about what is understood here as a unique property. About the stylistic property, as Springer had it, that does belong to one individual painter ›alone‹. In our words: that is to be found in one particular class of objects only and exclusively (while one tended to oppress the question if such characteristics could not be copied as well and thus, even if they were marginal details in style, become part of a stylistic paradigm). But was Springer correct in interpreting Morelli at all?

The truth is complicated, since on the one hand Morelli felt understood by Springer. He not only did not contradict Springer, but added chiefly positive marginal comments (›bene‹, ›vero›) to his copy of this particular review (see Anderson 1991, p. 19, note 17), and one might assume that Morelli, without having theorized the problem convincingly, intuitively had meant exactly what Springer now only was spelling out: that it was about unique properties, including the notoriously famous Leonardesque shape of ear (see GMM, Cabinet II [questions and answers section], particularly No. 16), that seemed to belong to that painter ›alone‹, so that one was entitled to argue with that kind of property as if one had found something sufficient to base authorship upon. As absurd as it did sound (and Morelli knew of the comical effect that he probably partly liked and disliked).

While, on the other hand, one began, at least in some cases and on basis of that newly found self-consciousness, to argue very arrogantly, assuming that absolutely objective arguments could beat all other arguments, brought forwards by all others who appearingly had no eyes to see at all. One occasionally acted as if the sufficient clue had been found. But the very term ›sufficient‹ (or any circumlocution) nevertheless tended to be avoided.

And it does also seem that Morelli, again: without actually and explicitly theorizing the problem, rowed back in his practice and in his methodological recommendations, since, as a matter of fact, Morelli warned of the isolated working with Morellian properties that he obviously did not want to consider as a sufficient basis to base authorship upon, relativizing the weight of the argument and the responsibility he was willing to take (for details see GMM, particularly the questions and answers section, No. 1 and passim). It has often been forgotten and it is still rather forgotten that Morelli recommended to test for such properties only after all others methods to test authorship had been exhausted (including testing for quality), and thus testing in fact for shapes of ear only in combination with testing for quality etc. Morelli, by the way, had seen Leonardo as an artist striving to represent the ›grace of the soul‹ (see Morelli 1891, p. 202).

Which did however not prevent him from inciting his pupils to mobilize exactly all the suggestive force inherent to the argument of the unique property: since this particular argument does in fact appear, at least in one example, if only on a level of polemical rhetoric and hypothetical: the not being there of the Leonardesque shape of ear seemed viable to dismiss the idea that a work of art (the Berlin Resurrection (Pala Grifi), now given to Marco d’Oggiono and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio) could indeed be by Leonardo himself (for this particular example see GMM, Cabinet III: Expertises by Morelli, with an expertise by Morelli juxtaposed with one by Wilhelm Bode concerning this very painting). In sum: The Morellians went as far as to say that: one might say that the unique property (the Morellian argument) could decide the question all by itself. But they never went as far as to put on record explicitly and verifiably that it in fact did.

A comeback of the unique property?

The unique property is rarely seen, but it is seen. In recent years, due to general technical progress, it had a comeback as the kind of property that – if it does not place an object into one particular class of objects – at least places an object very precisely into one specific historical situation, location or scenery. One may call this the ›matching edges‹ argument, if convincingly it can be shown that an object ›belongs‹ into, i.e. had its origin in a specific situation (this can happen of course on various grounds, which is why we prefer here to speak just metaphorically of ›matching edges‹).

Provided always that no mistakes have occured in the actual working process. But attributional studies evolve as a process of construction and deconstruction. And only recently has it – at least seemingly – also been shown that in the past one had mistakenly thought that the panels of the so-called La Belle Ferronière and the so-called Lady with an Ermine were coming from one and the same board. In May of 2015, appearingly, this possibility has been ruled out (see Noce 2015). And hypothetical constructions have to be readjusted taking this disillusion into account in some way.

(Picture: thenypost.com)

(Picture: eastendhistoricalmuseum.com)

Inspired also from learning from the past, but particularly from technological innovations the New York art firm Art Experts has now proposed that newly made works of art should have an artist’s DNA attached to eliminate the problem of mislabeling as best as possible in the future (see Steinberg 2016), while the more retrospective attributional studies have spotted the unique property also in actual fingerprints or any other clue that would be sufficiently indicative of a work’s origin.

One may also recall the hair from the polar bear’s rug in the living room of Jackson Pollock (Cohen 2013), but at the same time one must observe that, while it momentarily seems to be popular to lay stress on any other level of artistic production, stylistic properties on a level of representation are handled rather with a particular reluctance today.

If they are handled at all. And this perhaps due to confusion in the field, insufficient conceptualizations of stylistic criticism that still lead to a preferring of intuitive and less reflected practices, and perhaps also due to the suggestiveness of new technologies that raise seemingly new, but actually rather old questions: as for example: what exactly do we get from wavelet technology that analyzes patterns of brushwork? A sufficient indication of authorship? Metaphorically speaking: A fingerprint? Or something that is indicative only of a relative grade of spontaneity? Indicatice as to authorship only in very specific situations, provided that the field has already been substantially narrowed? Something of at best relative weight? With relative distinctive value? But how to determine that value?

And these questions as to the weight of particular arguments are exactly the questions the contemporaries of the Morellians – but also the Morellians themselves – did face in around 1880 concerning the Morellian properties.

The idea of the unique property, by the way, had its roots, as many of Morellis’s ideas and notions in writings of German connoisseur Carl Friedrich von Rumohr (1785-1843), who had, in the early 19th century, spoken of ›reliable peculiarities‹ (»sichere Eigenthümlichkeiten«) (see Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 155ff.). And what he had meant was that the way Giotto had handled draperies was the best indication of his authorship. Not sufficient all by itself, but sufficient in combination with certain other properties. And this example of an (still relatively) exclusive property might not only show the origins of the idea, but also – again – the dangers associated with it: since Rumohr’s example had been the polyptych from the Baroncelli chapel at Santa Croce, Florence. A signed work, but – the deconstruction of the argument follows the construction – considered by many connoisseurs as the result of only individually signed workshop cooperation.

2) Characteristic Properties and Single Likenesses

While the lure of any working with unique properties might consist also in the suggestion that it allows to ignore any alternative approach and that the indication of a unique property alone does, again: on a level of theory, seemingly and sufficiently allow a case to be closed, the working with other types of properties, namely the characteristic property, forces, with necessity, into the consideration of the relative distinctive value of such properties. The distinctive value of the unique property might be called absolute, and it can be taken for granted. The distinctive value of any characteristic property remains relative from the beginning. Because our knowledge is and must remain imperfect (which, of course, does also apply to the unique property), but as we will see also for other reasons, and we might start with saying that the greater the distinctive value the better. In a word: naturally one would be striving towards the greatest possible exclusiveness.

But ubiquitous in connoisseurship might also be the working with what we are calling here the single likeness, by which we do understand a working with single formal analogies, an linking or interlinking of objects due to the observation of likenesses, and this practice is a problematic practice indeed, since it might also be described as the active ignoring of the problem of the actual distinctive value of the very property that seems to link two objects. Why does this practice seem to be so common?

One could explain this by pointing to the suggestiveness of any formal analogy, might it consist in a total, partial or typological likeness of two areas of objects or two objects as such.

But since properties are not per se exclusive, a characteristic can indeed be a shared characterisic, i.e. one can possibly observe it in more than one, more than two classes of objects, and the risk that the formal analogy at hand, as suggestive as it might me, is of no distinctive value at all does always consist. And any practice that would ignore that very basic premise, not caring about distinctive values at all, must, again with necessity, raise suspicion.

And still the practice seems to be ubiquitous.

A single likeness does justify not more than a hypothetical putting of an object into a class of objects. And only two conditions provided one may speak of perhaps having found a characteristic mark that would allow to further consider common authorship: a) the exclusiveness (the greater the better) of the property; and b) the more than accidental nature of the property, i.e. its indeed being indicative of character and not of chance (which means that the relation between characteristic property and character as a whole has to be considered and verifiably established). And the distinctive value shows to be dependent from various factors: it would be the greater the more limited the number of classes a property does occur in, and the more regular/often a certain property does occur in single objects within one single class, and last but not least: the more it is indicative of character, i.e. the more the whole complexity of a character embodies in the particular property, because one may think ›pars pro toto‹ in at least two ways: in that there are properties that are just elements of a character, and on the other hand such ›more essential‹ properties that also may have a symbolical value.

We do not term the single likeness as an actual class of properties here (although the working with single likenesses might be called a typical phenomena, along with the working with unique properties and with characteristic properties). We do consider it instead, if the mere referring to single likenesses is not just about the beginning of a longer investigative process, as a characteristically superficial working with properties and, as it does show further below, a typical source of confirmation bias, although single likenesses of course can turn out to be characteristic properties in the end.

And still, even if this would be the case, we should remain cautious for at least three more reasons:

– we are dealing with relative exclusiveness only; characteristics can be shared; and characteristic properties are hence not sufficient to secure authorship all by themselves; and if they do, if accumulated, must be a matter of permanent discussion;

– character is not something stable, but something paradoxical: while being in existence with stability it does also evolve as any human; if we are looking only for consistency in our working with properties we would tacitly imply that character does not evolve at all (and a dangerous game of self-confirmation comes into play);

– the already named problem of any analogy: it can be full, partial or typological (with typological meaning here: variable elements that make a property would appear in various expected and also unexpected shapes; accidental elements may add, appear or again disappear); properties are classificatory patterns that impose the will for classification upon nature that might only correspond more or less (and sometimes not at all) to our ideas of order; and our ideas have to adapt and not nature (here: artistic production as nature); we constantly should keep in mind on how many levels actual human acts of interpretation come into play (and also as another source of confirmation bias).

[note: so-called left-handed hachures (hatchings; shadings) are often regarded as being indicative as to the authorship of a left-handed artist; the counterargument, however, criticizes a questionable assumption by saying: no matter if so-called left-handed hachures are characteristic in Leonardo (albeit not consistently so), it does not matter whether an artist is left- or right-handed, or even ambidextrous, but it does matter what an artist aims to do in a particular situation, since so-called left handed hachures can be produced, without any problem, by a right-handed artist as well; and therefore the finding of left-handed hachures does not automatically place an object into the category of left-handed artists nor into the category of works by Leonardo]

Meditating problems of style or: playing once more the ›game who painted what‹

Connoisseurs of the past have played ›the game who painted what‹ in many variations, but here, for once (and perhaps for the very first time), it is played as a thought experiment. With the purpose to meditate and to visualize before our inner eye what the problems of working with properties might be on a level of style, and in the field of Leonardo studies.

We may assume that we have amassed 100 photographs from any ›school of Leonardo‹ body on a table (Suida 1929 had offered 335 pictures; today we would also include pictures obtained by infrared reflectography). And our task would be to group these pictures according to stylistic characteristics. How would we, how could we proceed?

What could we do at all, if for a moment, all material and historical arguments would be excluded, as well as arguments on a level of painting technique, and only the phenomena of intimately related styles (the one problem Giovanni Morelli had specialized in) would be taken into consideration? We do nothing but think, and do arrange our thoughts in a series of three short digressions:

i) Would all the one hundred pictures share Leonardesque characteristics on some level? Or: About ways to construct and to deconstruct a ›school of Leonardo‹ body

Probably not all of the hundred would show Leonardesque characteristics, if this is what we are looking for, since the grouping of a ›school of Leonardo‹ body must occur on grounds of a association with Leonardo, but not necessarily on grounds of a merely or exclusively stylistic association. In can occur on grounds of written documents, dubious traditions, signatures, false readings of signatures and documents, and also false identifications of works that are mentioned in some documents. Since the historical record can be regarded as being more important than stylistic considerations we would probably have to expect the unexpected.

Since the variety of what is to be considered as being Leonardesque is unlimited it could be that few works actually seem to have much in common with other works at all. If we would work with the number of one hundred properties, it could theoretically be that we would have a sample of one hundred works exemplifying/representing one property each and only (a minimum condition if we would define a minimum of stylistic consistency). They would still have general qualities in common that would allow to categorize them as belonging to the Western painting tradition, as well as regional or national properties.

Nevertheless one would expect to find clusters, a set of common core qualities, since also the term Leonardesque can be defined very narrowly (and also with the aim to construct a more consistent body, using a low number of chosen and very specific properties, and this as a pre-conditioned combination that would make a very specific profile). If our sample of one hundred would be given by tradition, we would face exactly this problem that former generations have applied various ideas of orden upon a body that can be constructed in various ways (with and without the expectation of a minimum or maximum of stylistic consistency).

(Picture: thewalrus.ca)

ii) Sorting out quality?

One might be tempted to group the pictures only according to the criteria of quality, and come up with only two piles: a group showing (to adapt Kenneth Clark’s nice, but also abysmal saying) the ›grinning cat‹. While the other pile would show the ›grinning without cat‹ (compare Clark [1939], p. 165). In other words: due to some level of pre-information we would naturally know certain works by Leonardo himself, would define the level of quality found in such works as the inclusive/exclusive criteria, and we would establish a class consisting only of works showing the pure and classic Leonardesque, understood here in the narrow sense: only works by Leonardo’s own hand. Without any other hand interfering. A group without any mannerist rebellion. Perhaps with works having incited, posthumously, mannerist rebellions featuring distorted proportions and gigantic bodies with insect-like heads, but certainly a small pile with all the second-rate material excluded that is linked to the Leonardo pile due to some common characteristics, but only that, and not due to superb quality that in the end, as it is generally assumed, might make a work by Leonardo.

On this level our thought experiment does re-enact in some sort what, in Clark’s opinion, half a century of stylistic criticsm had been doing: one had purified the oeuvre by excluding other (sometimes disgusting) elements rather succesfully, so that, yet with some reserve, a »Consensus Omnium« (p. 7) could be presented: a classic core catalogue, to which one added that group of secondary works that could be seen as realizations of compositional inventions by Leonardo that had survived only in secondary works, and in the end only a few side problems remained.

Since most cases of Leonardo authentication, at some point, become discussions about superb quality and uniqueness of quality, we should at least note three things here:

– if one does check the half century of criticism Clark was referring to (the Morellian-Berensonian age) for phenomena of confirmation bias, one does detect for example the Pala Grifi again that shows that Morelli had not been able to tell ›Flemish uglyness‹ from ›Lombard quality‹ (the same applies to the Munich Madonna of the Carnation which had been named an ›attack on Leonardo‹ by the Morellians, besides that Morelli fought also very seriously against the Ginevra de’ Benci and the London version of the Madonna of the Rocks; and on the other hand managed to ›engineer‹ a particularly odd work, the so-called Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo, the embodiment of ›shocking nullity‹, into the Leonardo da Vinci oeuvre catalogue of a many of his followers; see GMM or Seybold 2014); and one might become suspicious if not the sorting out of quality, according to a certain idea of quality (before even one was willing to test for Morellian properties at all), can become, particularly if it is based on patriotic identification with Leonardo, the source of confirmation bias;

– the purified catalogue does reveal a problem with Boltraffio, ›repugnant‹ Boltraffio (compare again Clark [1939], p. 107); in other words: some works (at least the Musician, the Belle Ferronière, the Madonna Litta) seem not to know to which category they belong; one has, at least in hindsight, to take notice of secular debates which reveal the problem that it seems not to be that easy to tell Boltraffio from Leonardo on grounds of quality (and if older references, for example to other portraits by Boltraffio in Milan and on Isola Bella, have fallen into oblivion, confirmation bias is only enhanced); in the end one has to deal with the contradiction that Boltraffio on the one hand got harshly dismissed, and on the other hand, and very likely, still included into the the core oeuvre, while it remains unknown to what degree;

– perhaps most important: the Morellian ambition in dealing with the problem of intimately related styles had actually been higher than it is implied in the Cheshire cat saying (in which, in some sort, also an elitist position was hidden that yet implied that this position was the opinion of the common man; compare again Clark [1939], p. 165); and the Morellian ambition had actually been higher in that it had been about the detection of individuality also in the ›grinning without cat‹ category; about the detection of mannerisms in the realizations of common schemes for example, but above all: it had been, in general, about the detection of marked individuality as such, in which more or less strong individual artistic personalities did show; and the sorting out of quality, under certain conditions, might prevent exactly the raising of this question: was there a marked individuality in Boltraffio or Marco d’Oggiono and others? Something positively indicative of authorship (something specific that perhaps also resulted in a most specific repulsion in Clark)? Or was there only a collective lack of quality? A grinning without a body? So that a purified catalogue actually did justify a neglecting of the ›school of Leonardo‹, and thus, again enhanced confirmation bias, or better: again secured the results of confirmation bias?

iii) Pre-information and unexpectedly arriving news

At this level of our thought experiment we should point to the question if we actually are grouping pictures according to stylistic properties or according to preconceived ideas of style, that is: according to our pre-informations and general knowledge. Although the idea would be tempting, it seems hardly possible to look at Leonardesque pictures as if we had never seen pictures by Leonardo before. On this trivial level\\ pre-information is at play. But one might also use more particular pre-informations and hence group according to

– properties that are known to be ›Spanish‹, ›Flemish‹ or ›German‹ characteristics, aiming to reflect upon regional differences, based on the pre-information that leonardismo in fact has been a transregional phenomena; that however leaves us with the question to answer, to what degree Lombardic artists, on the other hand, might have adapted Spanish, Flemish or German habits;

– or we may group, as we have done above, according to former rules of inclusion/exclusion to understand better how certain connoisseurs of the past arrived to their conclusions; becoming aware that, in case we would like to operate with names and not only with more or less consistent groups, somewhere a beginning has to be made, and that all stylistic grouping rests, somewhere, either on the historical record or on a freely deliberate naming, and that stylistic criticism neither seems viable to replace the historical investigation nor one can think of stylistic criticism not-resting on the historical record (or on tradition) somewhere.

If we look back into the past we also become aware that connoisseurs of the past from time to time faced surprises that rather forced them to completely reorganize their classificatory schemes and way of thinking and to accept a new matrix: new definitions of problems at hand. At the end of the 19th century the finding of the documents concerning the Virgin of the Rocks law suit for example was followed by a chastening of the aggressive dismissing of the London version that only a little earlier had been regarded as being the more or less poor product of a ›copyist’s paw‹ (see Seybold 2014, p. 198, with note); now one had to accept that there were at least two intimately interrelated versions in serious discussion, to which Italian scholars have added, in the early 1990s a third version (see Caroli (ed.) 2000, p. 76f. [ex Chéramy]). And we might leave it here with saying that the more freely stylistic criticism does operate, which means, the more independent from the historical record, the greater the risk to construct, on mere grounds of style, unappropriate definitions of a given problem or even purely imaginary classes of objects. Every character does show consistencies and unconsistencies, which is only natural, since character is evolving in time. Yet if rules of inclusion/exclusion are defined based on the idea to homogenize a class according to a certain ideal, again confirmation bias will produce the wanted result.

While on the other hand, while the historical corrective is absolutely necessary, one faces the risk of relying, directly or indirectly, on unquestioned pre-informations, unfounded historical traditions (perhaps also the idea that the Gioconda is a unicum, since it might turn out to be in fact a multiple) or dubious sources that somewhere have been built in or ›engineered‹ into a pile of hypothetical constructions and may remain as tacit assumptions influencing our proceeding. And be it only if playing a game.

The problem of classes we don’t know (of)

It is perhaps easy to oppress the truism of a general imperfectness of human knowledge, but it is less easy to oppress the problem of classes of objects that we don’t know (of) – since this is about knowledge that we are obviously lacking – while attempting to classify objects.

This problem does exist in two variations: we might know of the existence of certain persons around Leonardo creating objects; but we might have no actual ascertained work by that persons (and usually little information either about persons creating objects around that persons around Leonardo); and we might – secondly – be totally unaware that there – perhaps – were another persons around Leonardo of whose existence we have not a clue at all unless such persons are named in newly upcoming documents.

A third problem has to do with connoisseurs of the past tentatively having put unattributed objects into certain classes and these hypothetical groupings having become traditions, with the hypothetical nature of these associations having fallen into oblivion.

As shown above we might be tempted to group works of art according to stylistic consistencies. But we have also seen just by defining rules of exclusion and inclusion, just by defining a combination of characteristics as a criterion it would be possible to contruct large numbers of relatively consistent groups. Only that all of these constructed artistic personalities would be purely fictional. And one might oppress or not the fact that connoisseurs of the past have constructed and again deconstructed classes created on grounds of visual evidence only. And these classes had been deconstructed again, since it had turned out that such classes had had not actual existence in reality, and were pure fictions.

If we now come back to the problem of classifying a single unclassified object, we face the problem of making strategic decisions about how to proceed. Are we considering the problem that there is a class of objects coming into question of which we know without having actual objects to look at? And are we prepared to face the suddenly being informed that Bernardino Luini had several sons who continued his workshop, so that suddenly and unexpectedly another class (or classes) of objects would come into question?

Perhaps less in the field we are discussing here but in more modern art one would perhaps face the problem of unknown forgers. And in sum: every class we know we can check for properties. Every class we know of (but have no works to check) we must still consider, as well as the problem of every class of whose existence we, perhaps only momentarily, don’t know at all.

Does the solution of this problem lie in a focussing on the unquestioned works by Leonardo, as well as in a checking of the unclassified object against such properties and vice versa? We might also be tempted to amass as many characteristics as possible to accumulate as much possible evidence as possible. But this proceeding does not at all eliminate the problem of confirmations bias, and in our perspective it is less about choosing between a qualitative or quantitative approach (both seek in the end for sufficiency in various ways) but about the question whether confirmation bias is avoided or not. Indeed the problem of unknown classes is only the most obvious reason for confirmation bias. A specific confirmation bias that cannot be eliminated at all (but only can be taken into consideration so much that it might boost general scepticism), while other sources of confirmation bias can at least be reduced. And about these sources that also have to do with the elementary working with properties we are going to speak in the following chapter.

3) Leonardo da Vinci Authentication – a History of Confirmation Bias

Authentication can be described as a process of testing alternative hypotheses, and it starts with the definition of a problem. The most simple case may be the testing whether something is ›by Leonardo or not‹. Or we may formulate the problem as ›genuine or false‹, or as the question if something is by known painter a or b (or unknown painter c). Not to mention the possibility of collaborative works.

The definition of a problem might change while working, and every definition of the problem has implications not only as to a reasonable but also as to an efficient proceeding. As to the allocation of resources, but also as to ›inner‹ problems, that is: problems inherent to a respective methodology. Since authentication may also be described as a process of testing alternative hypotheses of which usually one hypothesis is the more favored, more welcomed or more wanted one. This does not cause a problem unless research strategies are designed that lead to an actual privileging of the more favored hypothesis and a confirming of that hypothesis, because one wants it to be confirmed (and one does little or nothing to refute it or to confirm the alternative, less favored hypothesis/es, even if this was possible).

The result is not only a privileging of hypotheses, but also of outcome, inasmuch the privileging does show in classificatory decisions. In a bias. And more specifically in a bias that can be traced back to the active privileging, unconscient or not, of a particular hypothesis.

If this does happen one may speak of confirmation bias. And this seems to be the omnipresent problem in connoisseurship, in attributional studies, in authentication per se.

Confirmation bias does show on the two sides, as one may say, of the process: in the testing of the favored hypothesis it does remain more subtly hidden, and in the testing, respectively not testing, neglecting or only superficial testing of the less favored hypotheses it does show more obviously.

We already have seen that if we would dispose of unique properties, we would even be tempted not to test actively the alternative hypothesis, the ›or-not-hypothesis‹, as we may call it, at all, but only the Leonardo hypothesis, and indirectly the less favored hypotheses in one go. Since we just would check for the unique Leonardesque property, and thereby test actively for Leonardo. If the unique property, whatever it may be, does show – we might be tempted to speak of a sufficiently succesful testing of the favored hypothesis.

While a critique of this proceeding would focus on the question if convincingly it had been shown that the allegedly unique property indeed showed and/or indeed was unique (and that it showed in works by Leonardo as a rule). And for clarification’s sake one would attempt to look for the alleged regularity in Leonardo and for the very property in other classes of objects, that is: the whole body of the ›school of Leonardo‹.

If this looking for the particular property would be successful (and not result for example in endless and fruitless discussions about how to conceptualize alleged ›superb quality‹ of any kind), the critic would be able to show perhaps that the allegedly unique property in fact was not unique at all. And that the authentication process was flawed, since one had neglected the checking of other classes of objects. Which had resulted in an obvious, but somewhat hidden confirmation bias on the one side of the more favored hypothesis, and also in confirmation bias that showed as a complete lack of testing on the side of the less favored alternative hypothesis (the neckbreaking risk of working with unique properties exclusively does show here).

If this scheme, this example might not look very convincing due to an unrealistic scenario, one may recall here once more that a whole generation of connoisseurs had been tempted to check for properties such as the Leonardesque shape of ear (perhaps only due to a misunderstanding of Morelli that is ubiquitous even today, since the isolated checking is not what Morelli recommended), and that in the above mentioned example of the Berlin Resurrection one had, on the side of the Morellians, in fact little cared about by whom the painting actually was. To assume that it was by a Flemish follower of Marco d’Oggiono or by a Flemish follower of Leonardo himself had seemed to be enough. In other words: one had not much cared about positively indicative properties at all that possibly had enabled to specify authorship more precisely, more individually. The question, obviously, had been of little concern. What had mattered had been the refutation of the Leonardo hypothesis that had been proposed by Wilhelm Bode. And not the actual testing of the alternative hypothesis (which showed to be wrong, by the way, as well as the Leonardo hypothesis, but only after documents concerning the picture had been found at the end of the 20th century).

[note: it should once be said that traditional connoisseurship (by which we understand instantaneous intuitive opinion-giving here) is prone to self-deception and confirmation bias per se. Simply because it is based on memory capacity. While an actual and responsible assessing of the distinctive value of any property is not only about what one has seen in the past, but also about what one is going to see upon reflection. After having considered the given problem and after first judgment by eye, and after focussing mentally on something that one might not have focussed on in the past. (Or we must assume that the great connoisseurs of the past had seen anything anyway anywhere, storing everything, being able to focus in retrospect on whatever they wanted, while being informed on every historical document and every classificatory decision just being discussed in the field). From the standpoint of scientific connoisseurship, and also from the standpoint of the Morellian approach, traditional connoisseurship as defined above results in valuable hypotheses that may turn out to be reliable or not, but only that]

If we would not be as bold as to privilege alleged unique properties in our working, we would attempt to work with characteristic properties, and we would be tempted less to neglect the testing of the alternative hypotheses. Still it may occur that evidence is accumulated with the aim to have sufficient clues in the end in favor of the favored hypotheses. But one would have neglected to at least exclude the risk of ignoring the evidence in favor of any less favored hypotheses. And it may be that, by a critic, evidence may also be accumulated, now on the side of any less favored hypothesis, where it might add up to an even more impressive accumulation.

Which evidence would weight more, would be a matter of discussion, as it would be the issue to define – here or in general – a standard of sufficiency. And in some cases one might come to the conclusion that no actual classification of an object at hand would be possible at all (or at least for the moment). Indeed it would be more than an obsession with formalities to claim that in every single case it should be asked if sufficiency was possible, since otherwise the only hypothetical constructions might be seen as suggestive enough to become conventional truths and traditions (which has often enough occured in the past since one had not routinely asked if classificatory decisions were justified sufficiently, since one had tended, at least during the 20th century, to attribute the authority to make attributions to single authorities that, often enough, embodied – due to aura, charisma or myth – sufficiency).

Yet from the moment that an object has been placed into a historical scenario convincingly, one will have to think about strategies to place that object into classes of objects that are part of the historical scenario. And it would be negligent not to check for properties in all classes of objects. If this does not happen at all or only superficially, one may speak of obvious confirmation bias on the side of the less favored alternative hypothesis or hypotheses.

And it goes without saying that the problem becomes even more dramatic if only simple likenesses get accumulated, and no distinctive value of such likenesses is made evident at all.

An indicator of quality in authentication research?

Wilhelm Suida did introduce his classic study on the school of Leonardo (Suida 1929, p. 9) by saying that once Leonardo da Vinci had been considered to be a very prolific painter, but that now he was seen as a dreamy artist with a very scarce oeuvre of finished objects. Even someone with little interest in Leonardo and his school might read this as an illuminary example as to what degree history (or truth, or what people believe is the truth) can be bent.

The school of Leonardo has been an object of more intensified research in the last past decades and due to technical possibilities the image of Leonardo – and his workshop – is again changing, but as to the history of Leonardo authentication we may say at best that omnipresent confirmation bias has usually been countered chiefly by those critics not having been involved in a respective case initially. And this does not add up, to put it diplomatically, to a very efficient proceeding. Hypotheses are brought up by one camp and get refuted by other camps, while on the level of theory it seems to be rather easy to define measures to avoid confirmation bias that shows on all level of things and not only on a level of style.

Given the said it is rather obvious what an indicator of quality would be: it would be the amount of resources in time, money and intellectual capacities that is invested into the testing (and possibly confirming) of the less favored hypotheses. And this idea would not only pertain to Leonardo studies, but to all phenomena that have to do with one central figure within a swarm of secondary interest figures, in other words: that have to do with cluster phenomena on the level of (intimately related) styles and/or on the level of working practices (where it does result in material properties, common or relatively exclusive, or unique); and the idea would also apply to attributional studies in general.

[note: whenever the notorious rhetorical question ›who else but Leonardo?‹ is heard, a speaker attempts to hand over the task of demonstration to a listener, implying (or not even this) that all reasonable alternative hypotheses have already been excluded; the moment this question is heard is exactly the moment to recall why a qualitative indicator might be necessary]

Consequences and Conclusions

All said here applies to the working with single properties, but also to the constructing of (perhaps) unique profiles of artists that consist of particular combinations of properties. Even if in the practice of authentication studies we rarely do see the isolated working with isolated properties, but rather the accumulation of clues and arguments (that result in, make or indeed are the checking for a specific artistic profile), it is in the end about something (on a visual, intellectual, physical or chemical level) that makes, or is meant to make the difference. And this is usually a property, mark or clue – unique or not, but at least relatively distinctive – that is thought to be positively indicative as to authorship; and therefore the isolated looking at properties and at the structure of singled out arguments might be all the more be justified since this focus, which is: this relative, but decisive weight indeed given to single arguments often does remain hidden within clouds of ›rhetoric of attribution‹, and since connoisseurs, including Morelli, have not shown to be very extroverted or talkative as to revealing what, in a particular case and for them, indeed made a difference (see below).

All said here applies to the problem of Leonardo and his school but also to analogous situations (Giorgione; Rembrandt; Van Gogh).

And all said here applies to stylistic properties on the level of visual representations but also to material qualities on the physical or chemical level of objects.

On a very basic level of things it may be hard to decide whether something is very profound or just trivial. If we shift our attention on a pragmatical level of working practices one will notice a rather strange lack of tools and aids in attributional studies. Neither have properties been compiled that connoisseurs of the past have worked with, nor methodological problems been ›harvested‹ and compiled in order to make often seen fallacies known and to avoid them in the future.

One might assume on that grounds that no problems whatsoever have existed in attributional studies or authentication practices in the past; but since it is also a trivial problem to amass errors that in fact have occured in the past, and also very dramatic errors in the field of Leonardo studies, and since one must also diagnose the lacking of cooperative efforts, it can hardly be said that no problems do exist at all. And it seems that it indeed would be reasonable to once read the history of Leonardo studies as a history of perception: Not only could it be shown that connoisseurs of the past have often worked with completely different properties compared with connoisseurs of today (if facing the same or analogous problems). Morelli for example had based his idea of the style of Leonardo’s pupil Salai on the observation of the seemingly characteristically short second (upper) phalanx of the thumb in three representations of St John the Baptist (and appearingly also on the observation of ›wire-like‹ hair) (see M/R, p. 338), while today one would not immediately associate, as Morelli did here, the (smaller) Louvre St John with Salai as the author, nor, perhaps, give much weight to old and rather dubious historical traditions that had associated certain works with certain names (the Ambrosiana version of the Baptist), perhaps also noting that a peculiarity had been associated with individuality, while it also might have been just part of a common scheme. The informations, by the way, as to Morelli’s seeing and constructing of a category on grounds of historical traditions and stylistic observations often, and also in this case, have to be extracted from letters and were not even disclosed to a scientific community in the past, but only to a few associates (the same pertains to the ›double-ear‹ in Luini, see Seybold 2013, p. 58ff., and the characteristic formation of clouds in Marco d’Oggiono and his followers, see GMM, as above).

But to read the history of Leonardo studies as a history of perception would also allow to ›harvest‹, to compile and, in a way: to exploit that history for crucial methodological problems (that we inherit anyway), since, as one might assume, virtually any problem does show here, and in often very drastic ways. Due to the above named mythological status of Leonardo, due to the above named urgency, but also – last but hardly least – due to the ever intriguing multi-dimensionality of Leonardo da Vinci himself (for an outline of the history of Leonardo scholarship, seen under a very particular angle, see Seybold 2011).

If such methodological problems, as it is attempted here, would be compiled in abstract form, one would also escape the problem of morally questionable fingerpointing, since it would not be about a museum of individual errors that have occured in the past, but about a number of intellectual problems that, however, are rather typical problems and show, while the technical investigations make progress, in only new configurations of elements. The problems of a working with properties shift, as one may say, to the field of technical investigation, where however the same problems of classification and interpretation do show. Which would be one reason more to take advantage of experiences in the past and particularly that won on a level of long practiced stylistic criticism.

One does wonder, in a word, why the the ›game who painted what‹ has not been played in the past as it is played here for once: we actually do nothing, in that we contemplate methodological problems, but to think. Aiming at compiling in one in the same picture: what one can do, and what can happen.

4) Appendix:

a) A hierarchy of arguments (according to their weight)

unique property: greatest possible (in theory: absolute; unconditioned) distinctive value; at the same time greatest possible responsibility associated with the respective argument; it is rare that ever it can be shown that a property is totally exclusive (and we never can assume to have perfect knowledge), but people tend to think that at least on the level of superb artistic quality this is possible (since this is the level to where followers and forgers can not follow the artist); which is why in scientific connoisseurship (or in attributional studies with a scientific ambition) strategies to conceptualize quality (here understood as the ›goodness‹, thought on a scale from ›good‹ to ›better‹ and ›superb‹) are necessary, including strategies to guarantee intersubjectivity and mutual understanding; the same applies to material qualities (here understood not as ›goodness‹ but as ›individual nature or essence‹ of materials); the analogy, as one may say, applies also to intersubjectivity, since laboratories need to secure to have common standards, if attribution and authentication is meant to be a common scientific effort, as science per se is a common effort of a scientific community

characteristic property: the greater the exclusivity, the greater the relative distinctive value, which, however is dependent also from other factors: the relative distinctiveness of stylistic regularities in a character and, not to forget, the type of relation between characteristic and character as a whole (the characteristic might be just an element of character or embody a whole essence of an artistic personality)

single likeness: just hypothetical distinctive value; hypotheses can be based on single formal analogies, but distinctive value (if there is any) has to be verifiably shown and not merely suggested

b) Working with properties: often seen problems and fallacies named

General problems:

– compliance to scientific standards is not wanted (which makes cooperative action impossible, since neither actions nor reasonings nor standards of any kind are disclosed; which also has the implication that actions of others complying to standards remain relatively unefficient);

– basic ideas of science as for example transparency, verifiability and intersubjectivity are not understood;

– classificatory decisions are neither explained nor made verifiable;

– classificatory decisions are explained, but not verifiably so;

– negligence as to asking for sufficiency (anything that has been attributed amasses in a ›attributed to Leonardo class‹ no matter if decisions are based on no reasons at all, hypothetical grounds or cogent arguments);

– general liability to confirmation bias;

– imposing of a binary (›digital‹) logic upon everything (suggesting that always it is possible to decide whether something is the case or not, which would imply that no acts of interpretation are occuring exept the deciding between two categories ›being there/not there‹, while the checking for stylistic properties hardly faces the problem if a property shows or not, but rather the problem if something can be interpreted as showing in some way or not again (like a signature shows at best in relatively consistent ways and not like a scheme that would be produced identically; the metaphor of the fingerprint implies identity while, at least on a level of style, the use of the fingerprint metaphor can be misleading and the analogy shows in a more hidden way: in that we often face only fragments of what we would expect to show again completely);

– hiding, covering up or blurring of interpretative acts and only hypothetical constructions by use of numbers, particularly conditioned probabilities, that imply (but rather suggest) scientific rationality, exactness and cogent reasoning;

– blurring of the categories of full, partial or typological identity of properties;

– lack of reference material; the existence of one reference work only does only allow to make hypothetical assertions as to whether something detected might be a characteristic property, since no regularities can be shown (no evolution or stability of character in time; if however the single reference work is the realization of a scheme, it can at least be shown in what it differs from other realizations of the scheme, but these differences might also be the result of chance and not of character, or the result of a character inviting chance in his working practices; the same applies if an overall style can be detected, in the representation of one part, but also in the representation of another part and in the very same way, so that a regularity in style might at least be hypothetically postulated); unique properties can also hypothetically be postulated on the grounds of one single reference work, but to show that such properties are indeed unique, also (all) other classes of objects have/had to be checked

Problems associated with the notion of unique property (in relation to confirmation bias):

– confusion of notions; blurring of notions (also due to deliberate negligence, as can be observed in the Morellian age); negligent reading of Morelli or general ignorance as to the history of connoissseurship (as can be observed in many projects that make, but on unsufficient grounds, a reference to Morelli);

– misunderstanding of the typological concept of working with properties and stylistic regularities, hidden in the Morellian approach (where this concept, unfortunately, was never spelled out, discussed or further developed);

– no actual or negligent demonstrating of uniqueness (checking of alternative classes of objects);

– underestimating of the skills of followers, copyists and forgers (implyling that ›superb quality‹ cannot be copied and have a life of its own)