M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Those Who See More

Those Who See More

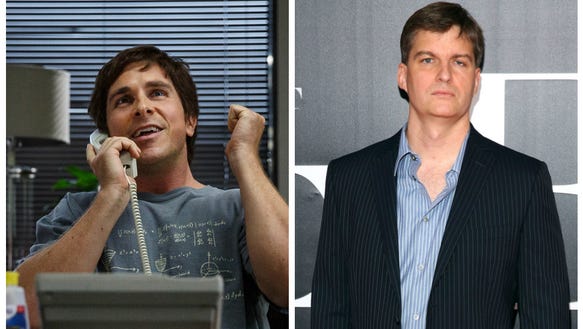

(Picture: youtube.com)

The one good thing about the global financial crisis (perhaps the only good thing) is that it stimulated brilliant movies about the crisis. Meant to explain it, to reflect upon it, to have audiences live through it from various perspectives, and to have spectators muse about what it was, how it is to explain (in hindsight), and perhaps also: about what to learn from all this.

The interesting thing from a humanities point of view is now that various movies have developed particular narratives to depict, to reflect upon and to explain the crisis, and one of these narratives, adapted by the 2015 movie The Big Short, directed by Adam McKay and based on the brilliant book by Michael Lewis, one might sum up by saying that there were a few people that could see more than other people. People who saw it, the crisis, coming. And this, this particular narrative, is what we are interested in here.

The movie depicts people, particularly Dr. Michael Burry, who in some sense is the embodiment of the whole narrative, who – in a retrospective view, we must add – had seen more, and who also had been able, to various degrees, to use this ›more‹ to their own benefit.

Which might already be an interesting point to start a discussion about the narrative of few people seeing more than others, and the film does also bring out the question of morality very well (morality represented rather by other people and not necessarily by Dr. Michael Burry, despite his sense of justice and morality that accuses the system to be fraudulent): isn’t someone who sees a crisis, a national, even global crisis coming, obliged to warn (and thus to act against his own benefit). At least to attempt to warn (since he might not get through). And here we see that the movie, and the book it is based on, actually discuss a very ambiguous narrative: there were some, able to see more than others, but they still used this discernment chiefly for their own purposes (when betting against the American economy). And, at close inspection, there were also several, and perhaps not so few people, within the system, who also could see more, but could not use this discernment to their own benefit, not did they speak out (perhaps this would have meant to act against their own benefit).

But now, one might say on the other hand, we have their stories, and we can learn from them and discuss the stories of some seeing more than others. Which is what we do here – in a context that is actually dedicated to art and connoisseurship (and thus questions of seeing, perceiving, interpreting and – perhaps: acting). In a section dedicated to bring out the complexity of the narrative of Those Who See More, its various motives, and some questions associated with it.

(Picture: summagallica.it)

Wonderful find!

(Picture: banknotesgallery.com)

Adagia:

If Erasmus of Rotterdam had collected his Adagia, proverbial sayings from ancient literature, today, he might have mused more about the proverb ›In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king‹. Actually Erasmus had not much to say about it, but whoever browses the Adagia does know that Erasmus did not only collect, but used these sayings to comment about contemporary affairs, and that the Adagia as a whole offer much more wisdom to reflect about, well, the housing crisis of 2005ff., than just this one saying, and much more than one might think of. In any rate: Erasmus, who transmitted antique wisdom, had much to do with contemporary writer Michael Lewis, who told the story of Dr. Michael Burry as the story of the one-eyed, being king among the blinds. See Inter caecos regnat strabus. See Burry, Dr. Michael.

PS: Several humanists, by the way, used their findings in antique literature for their own benefit and as more exclusive knowledge. But not Erasmus, who was anxious to popularize them, so that everybody could make use of them.

Blue Hour of Capitalism, The:

(Picture: youtube.com)

(Picture: jmmnewaov2.wordpress.com)

The equally brilliant 2011 film Margin Call has a different narrative. It does condense the whole crisis into the story of one night (plus about another 12 hours). And for the cynic capitalist, there will indeed (and perhaps always, as we may think) be a bright new day with a capital lunch and a spectacular view.

Is there someone seeing more? Is there someone seeing it coming? Yes, there is. Chiefly it is the one who is able to work with numbers (background in rocket science). It’s just numbers (but the pay on Wall Street was better), and seeing more just means here to save the firm, to save the cynic capitalist.

Margin Call does not challenge the viewer with very complex explanations. Instead (as the cynic capitalist played by Jeremy Irons) has it: Explain it to me as if I was a young child. Or a golden retriever.

PS (quote from Wikipedia): The name Cynic derives from Ancient Greek κυνικός (kynikos), meaning ›dog-like‹, and κύων (kyôn), meaning ›dog‹ (genitive: kynos).

(Picture: cnbc.com)

Bubble:

No one can see a bubble, which makes it a bubble.

But there are identifiers (marks), like for example…

No one can see a bubble, which makes it a bubble.

But,…

[Infinity; but see also: Identifier]

Burry, Dr. Michael:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Burry

Does anybody know that T-shirt motive?

(Picture: usatoday.com)

Credibility:

Very interesting problem. First we may note that Erasmus has a proverb saying ›It’s a fine thing to deceive a fox‹ (Adagia, IV.V.22). Because the real Dr. Michael Burry faced the problem of not revealing too much of his knowledge vis-à-vis for example Goldman Sachs. The books of Michael Lewis perhaps makes this more clear than the movie, in saying that Dr. Michael Burry, in specific situations, had to lay stress on appearing more like an amateur, and not as someone seeing as clearly as a lynx. See Lynkeus.

Drum cover:

(Picture: youtube.com )

Yes, one can see that he’s drumming (the end credits have also a drumming mentor). With the piano it is easy: one does immediately see that, in films, actors are actually not playing. How is it, for example, with violinists? This, in Robert De Niro’s The Good Shepard, is meant to be the ultimate test within the film itself: is the Russian defector who he claims to be? He is not, but he does play very well (Tchaikovsky, I believe). Which means: the test actually meant nothing, but allowed the other to say: I just wanted to hear something from you that was true. See here.

Exclusive knowledge:

We know this from art connoisseurship. Decisive knowledge (identifiers of authorship of pictures) is not shared, but kept secret, since authority, reputation, and often money, is at stake. Scientific connoisseurship demands transparency and verifiability, which is why scientific connoisseurship has never become very popular among those being dedicated to art connoisseurship.

Erasmus did share. Are we on the right side, if we are sharing as well? Only if everything sticks, and every name is spelled correctly as well (I have to check it again).

Identifier:

What does it mean if an alligator resides in a pool? Or if a stripper owns five houses (and a condo)?

The Big Short has this elegant cut. To Mark Baum saying into his phone: Hey, there is a bubble.

But Michael Burry knew it much earlier. Why? Increase of mortgage fraud (as I understand it). The matter is complicated and Michael Lewis has made an elegant decision as well: In his chapter which does introduce Dr. Michael Burry he does quote an email by the latter explaining the matter. Is the reader thought to understand it? Or is it meant to demonstrate: this is how someone argues who turns out to be one of those who see more.

Inter caecos regnat strabus:

Adagia, III.IV.96. – Erasmus basically gives us some variations. Strabus actually translates as ›cross-eyed‹, but another, Greek variation has ›one-eyed‹ (›In the kingdom of the blind the one-eyed man is king‹). – The commentary (Collected Works of Erasmus, vol. 35) informs as that there is also ›In tuneless company the lark can sing‹. (See also Drum cover).

Investors’ revolt:

Dr. Michael Burry of The Big Short faced such thing. Not chiefly because, as I do understand it (specialists may correct me), because they did not believe what their fund manager had seen (resulting with him betting against housing bonds), but more because there was also the question of timing, the question of how long it would take the system would collapse, and how long it would take until the fund would actually make (a large amount of) money, and not loose it due to the paying of premiums on credit default swaps.

But the more abstract question is. Can the one who seems to see more get through with his message and win crucial support (of investors, or of whoever is interested in his acting, based on seeing more). See also Credibility.

(Picture: wwf.de)

Lynkeus:

Does not seem to be a very popular figure from ancient mythology – Lynceus (Argonaut). But one of those who see more. More clearly. Just better. See also the good-old academy of the lynx-eyed: Accademia dei Lincei.

Morality:

The paradox morality of the film’s Dr. Michael Burry is that he actually, at least to some degree, reveals what he believes to know. Not as a whistleblower. Not to the general public. But by betting against housing bonds he reveals his convictions, and in some sense also openly does warn the system. Resulting in few others, and later more and more, following him. This is the story of few people seeing clearly, people driven by self-interest, while many others could not or did not want to see. Then more and more people are seeing clearly, while not being willing or able to stop the crisis from unfolding (if this had been possible anyway).

A certain danger may lie in the fact that the more one stresses the visionary genius of the few, the more the whole system gets excused. The story of the Emperor’s New Clothes has a child in the end to speak out and to say what everybody actually could see. But the child is no genius. It is simply unaware of social positioning (all others in the tale simply do not risk to speak out, fearing for their social status). But how difficult was it to see the crisis coming and the risks inherent to some financial instruments? The film’s opening speaks of those who simply looked, but shows a Dr. Michael Burry actually combining various faculties: historical knowledge (not to be underestimated, the reference to the Great Depression is frequent), financial insider knowledge as to the construction of products, curiosity, obsessive will to study the structure of housing bonds, and last but not least: this unsverwing will to act based on his convictions. Moral authority, within the movie, does exist, but within individuals, not as part of the system (in form of smart and working regulations). The chair of moral guidance to the system seems to be empty. Moral authority is absent, that is, replaced by disfunctional self-regulation, which is, in some sense, embodied by an present/absent Alan Greenspan.

Nietzsche:

The Big Short has a motto by Mark Twain which more or less says the same as Nietzsche’s ›Convictions are more dangerous foes of truth than lies‹. I am a bit suspicious as to this saying since I have once heard a local politician quote it. But anyway…

Numbers:

Yes, numbers. But also some words. And many words. Actually 9 hours, 17 minutes and 52 seconds just words (and also some numbers). Here.

Outsider:

Well, they were not complete outsiders. All acting within the system while distrusting it. One may also stylize people as outsiders (›I am not hanging out with these idiots‹, says someone, still near them), and Dr. Michael Burry initially had a blog. Which is why he was picked by capitalists to become a fund manager. And integrated into the system. As someone who detected patterns no-one else was able to see.

Re-checking:

The question if The Big Short does explain well is discussed here.

Social awkwardness:

The glass eye, the social awkwardness, the obsessive study of charts, and, in hindsight, being seen as the one who had looked and seen more. This might be the story of Dr. Michael Burry. But the film, undermining nicely its own narrative, does also show a counterpoint. The one ratings agency has a clearsighted woman with eye problems and some kind of glasses. But as she reveals knowing much more than she initially does show, she does take her glasses off. Looking at them, and, in some sense, looking at us. The film does imply that she did not bet against the American economy, but who does know. At least she did not speak out. We have bosses, we have competitors, and you, Mark Baum, with your virtuous stance are just a hypocrite.

Three Wise Monkeys:

Has anybody seen this yet? There is a fourth monkey (that perhaps did not get his own emoticon yet…).

Twain, Mark:

See, perhaps unexpectedly, Nietzsche, and replace ›lies‹ with ›not-knowing‹ (ignorance).

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES | FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS | HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION | ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS