M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

Two Museum’s Men

A snippet of transatlantic museum’s history we give here. But there’s more than that. Who would name Erich Steingräber (1922-2013), if asked to name one or even the outstanding German connoisseur of the second part of the 20th century?

But it was Thomas Hoving (1931-2009) who did associate Erich Steingräber with connoisseurship and even called him an »universal connoisseur«. Steingräber (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Steingräber), better known probably as art historian and museum’s director, to whom yet, according to his testimony, Hoving owed so much as to his very connoisseur’s skills. And there is something else: Who would link Hoving with connoisseurship, one might provocatively ask (and yes, we know that he was editor in chief of the Connoisseur magazine for some time), because this is also about 20th century styles of connoisseurship, and more specifically about populism as opposed to (or combined with) manifest scholarly principles.

Two Museum’s Men: Thomas Hoving and Erich Steingräber

(Picture: csfineartscenter.org)

(Picture: artnet.com)

Few art historians would take the risk today of telling the public »how to become a connoisseur«. But Thomas Hoving (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hoving), in his Art for Dummies of 1999 did. On not even four pages he did that (we refer to the German edition of that book here: it’s actually a bit more than three pages).

Which does not mean that Hoving did claim that it was possible to become a connoisseur in twenty minutes. Or sixty. Or in three hours. Connoisseurship for Dummies would have been an even more provocative title to that book, but on these three pages or so Hoving went back in history, back to his early days as an assistant curator at The Cloisters (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cloisters), recalling how once himself got taught how to become a connoisseur (of primarily medieval art). By another connoisseur that Hoving, interestingly, does not name in his Art for Dummies and simply refers to as a young German »super-curator«, who had come to New York to study the collections. And who did study with Hoving, telling him how to tell an authentic work from a fake and many other things, with finishing almost every sentence with a German »nicht wahr?« (but this detail is not given in Art for Dummies neither).

(Picture: zvab.de)

(Picture: muenchen.bayern-online.de)

(Picture: tomhoving.com)

Hoving does name Erich Steingräber in his memoirs that can be found online (http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/hoving/artful-tom-chapter-twenty-three5-28-09.asp), but it is worth noting that, in German-speaking countries, Steingräber, as far as I can see, has not yet been acknowledged as a connoisseur at all, nor have his principles of connoisseurship ever been discussed by writers dealing with the history of connoisseurship. And even as to the early biography of Erich Steingräber we have actually to turn to Thomas Hoving, who did write, as it were, Steingräber’s memoirs as well, in re-telling what Steingräber once had told him about his life, and, for example, as to how Steingräber did actually manage, being wounded as a soldier, to survive the war.

But this is not about biographies or disruptions within biographies in the first place, or about disruptions within the history of art history as such. Instead we would like to go on to quote a short passage here that could also be quoted within the sections on the Iconography of Connoisseurship on this website. Because Hoving did describe, and this very vividly, how Steingräber did act in front of works of art, how he circled them, questionable ones, or »utterly authentic« ones (and both men, as it is common among commoisseurs, did share, among other things, a more or less decided disregard as to art historical theories, and as to mere art historical book learning).

(Picture: amazon.com

»He’d approach a work of art like a hawk circling its prey. Erich would scrutinize the piece for several minutes, saying nothing, his eyes darting over every inch of it; then with a sure motion he'd seize it. He'd hold whatever it was far from his eyes and then bring it close, turning it completely around, upending the thing, glancing several times at its bottom and interior. He'd stare at it without comment. Eventually, words would slip from his thin line of a mouth in a litany, gathering speed: ›Beautiful,‹ ›Grand,‹ ›Spezial, nicht wahr?‹« (source: artnet.com)

The Cloisters (picture: Jose Olivares)

(Picture: amazon.com

»He’d replace the work on the table, turn to me, eyes glowing with delight and say, ›Tom, excellent piece! Condition perfect, better than the ones in Dresden, Berlin, the Cluny and Cleveland. A truly surprising example of brown enamel, nicht wahr?‹ And he’d launch into a learned and intriguing description of how the unusual substance of ›brown enamel‹ had been manufactured during the Middle Ages, complete with statistics on the temperatures required in the oven to fire and produce the enamel which had a lovely matte brown hue like burnished ancient gold.«

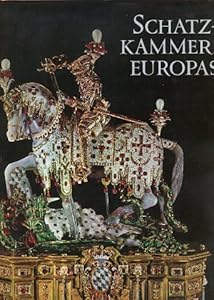

The godfather behind this relationship between mentor Steingräber and pupil Hoving was »Monument Man« James Rorimer (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Rorimer), then director of The Cloisters, who had actually invited 35year old Steingräber to New York for six months. And the young German curator, who had not been involved in the Nazi’s looting of art treasures all over Europe, was to become, only years later, in 1962, director general of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum of Nurimberg (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanisches_Nationalmuseum) and, in 1969, director general of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bavarian_State_Picture_Collection). And since this is the backstory to the above mentioned Art for Dummies tutorial on how to become a connoisseur, we give here another, longer, passage from Hoving’s memoir (source again: artnet.com):

(Picture: amazon.com

(Picture: metmuseum.org)

»He never held back what he thought of a work of art and pointed out to Rorimer those he believed were fakes, even if it were a recent Rorimer acquisition. One, thankfully not acquired by Rorimer, was a gem of The Cloisters, a lovely little reliquary of the thirteenth century that had been given to the museum by one of its most generous benefactors, George Blumenthal, who had been entranced by medieval reliquaries and fine emeralds. This reliquary was in the shape of a svelte silver index finger wearing a ring with a sizable emerald set upon a circular mount with an inscription in niello, a kind of striking black enamel, and supported by a thin-legged tripod. The relic was supposedly contained inside the unusual receptacle. The thing had been published in art historical books and periodicals for decades and was considered the finest of finger reliquaries.

Steingraeber went through his examination dance, set the finger on the table and barked, ›Fake!‹

›Come on!‹ I protested, knowing how important the piece was to the museum.

›See these three tiny stamps on this leg?‹

›I’ve been told they’re makers’ marks,‹ I said.

›Sure, but not of the thirteenth century. This particular type of three marks set together is typical of French eighteenth century gold workers’ marks.‹

›Added later, perhaps?‹ I asked haltingly.

›Here, take your glass. See, they are not stamped, but cast into the silver.‹

›Erich, one little deficiency…‹

›Here's another, ah, ‘little deficiency,’ Tom. Try to remove the ring.‹

›I can't, it’s part of the silver making up the finger.‹

›Which means that the forger probably made it from photos. Because on all other genuine medieval finger reliquaries the ring can be removed. That's because the donor, moved by the religious nature of the saint’s relic, slipped a ring off his finger and put it on the reliquary to honor the memory of the Saint. Nicht wahr? And, as for this 'saint,' just who is it?‹

›We always assumed that the name is on this niello inscription surrounding the circular base. Though I admit we’ve never been able to decipher the name of the saint.‹

He took out a penknife and to my distress plucked out the tiniest of slivers of the niello.

›Taste it.‹

It was a disgusting oily tar. ›I guess it's not niello,‹ I said, resigned.

›But don't tell me that huge emerald is also…?‹

›Genuine. As you told me George Blumenthal collected reliquaries and appreciated emeralds, well, this fake was specially tailored for his desires –– typical, nicht wahr?‹«

See also: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/471280

Carolingian ivory plaque (picture: christianiconography.info)

If Thomas Hoving does give us an accurate account of this conversation, we don’t know. We simply state, and it is obvious from the passage quoted above, that Hoving was one of the actually quite numerous connoisseurs that also had a taste for creative writing. Literary writing, not only writing of popular non-fictional books. And it is also worth remembering, because this is about opposing styles of connoisseurship, but not about having these opposites necessarily personified by these two man in pure simplicity, that Hoving, at this moment in time that this conversation must have taken place, was about to publish his voluminous dissertation on the topic of Carolingian ivories of the Ada school (see: http://books.google.ch/books/about/The_Sources_of_the_Ivories_of_the_Ada_Sc.html?id=6zocnQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y ; and see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolingian_art). It is hard to imagine to have a German director general of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen publish an Art for Dummies book (not to mention a book entitled Make the Mummies Dance), but it is also hard to imagine that this literary image of apprentice and German »super-curator« does give the full picture of these two men’s relationship. In the Art for Dummies book, by the way, it’s the German mentor who tastes the tar.

This is not the place to fully discuss and to compare these two museum men’s careers or even their whole biographies. A critical, but fair obituary, as it seems, that is also very worth reading, has been dedicated to Hoving by the New York Times (see: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/11/arts/design/11hoving.html?pagewanted=all), while the literature on Steingräber, up to the present day, remains, despite his claimed influence, unfortunately less than scarce (but see for example: http://muenchen.bayern-online.de/magazin/kultur/kunst/artikelansicht/erich-steingraeber-geburtstag).

While obvious differences in style between these two men can hardly be overlooked, both of these two connoisseurs rather seem to represent what is sometimes referred to as a »basta vedere«-school of connoisseurship that neglects, if not dismisses the permanent exchanging of rational arguments and the reflection upon what looking actually is (since, despite of the common suggestion, the one way of looking at art, at form, does not exist at all).

The postwar years were certainly not the period of connoisseurship’s history where theoretical reflection was at its height. But it is also worth recalling that a connoisseur of the calibre of Max J. Friedländer, occasionally had made clear that the eye is not just the eye, but linked what Friedländer called the »gedanklicher Apparat«. Populism in connoisseurship on the other hand might mean to neglect or even to dismiss this very reflection upon the intellectual apparatus, linked to the eye. And the reflection upon in what the intellectual apparatus of one human being might be different from that of another human being.

If populism prevails, connoisseurship runs in danger to develop towards the mere subjectivism that, due to once established positions of power, just prevails at a certain time (while it is not or not only prevailing because of its good arguments brought forward, shared with and explained to everyone). And this might, paradoxically, be the case despite the »basta vedere«-school’s wanting to democratize the field of connoisseurship and that recommends to everyone, to every »dummy«, the being taught by the German »super-curator«, who did not share his experiences with everyone, but at least in Hoving’s account, does explain his reasons and reflections to the pupil.

(Picture: amazon.de)

A quote from Petrarca’s account of being overwhelmed by the sheer joy of looking, on the summit of Mont Ventoux, on April 26 of 1336, has been chosen for the mourning address dedicated to Erich Steingräber in 2013, and the sheer joy of looking, the being overwhelmed by a new vision of the world, was probably never as pure, and also, one might imagine, never as innocent, as immediately after the ending of the Second World War, when Steingräber did embark on the adventure of looking at art, at a time when Europe lay in ruins.

It is less apparent in Hoving’s biography, but the two men’s experiences during war times have to be taken seriously into account, if discussing their looking at the world, and especially at cultural, artistic products, after the war. It is about the invisible dimension of any looking at art that inscribes into anyone’s looking. And this might exactly be what one may also call the blind spot of any »basta vedere«-school. Or one might call it in the end – its style: the deliberately not wanting to discuss what separates one human being’s vision of the world from the other human being’s vision. And one might think, one time, about the consequences thereof, not only as to connoisseurship, but as to the looking at life as such.

(Picture: tomhoving.com)

(Picture: nytimes.com)

(Picture: metmuseum.org)

(Picture: amazon.com

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS