M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

First Series

Visual Apprenticeship  |

The hero of the apprenticeship novel (›Bildungsroman‹) usually does not see anything. Which is: He or she yet has to learn of how to see. And of how to interpret things, which is: of how to live. But what exactly to learn? And how, and taught by whom (and how to avoid deception)?

Is it, by the way, true that there is no such thing as a ›visual apprenticeship novel‹? Or is any Bildungsroman a tutorial of how to see?

At any event: The new series Visual Apprenticeship that starts here is about such questions. But the series is not meant to replace a collective visual apprenticeship novel. May others teach of how to see, or start a ›school of seeing‹. The following is merely about collecting materials, about compiling an anthology with scenes wherein a someone learns something about seeing, about the dangers (or advantages) of not being able to see, or actually does, in practice, learn of how to use his or her eyes (and mind). And I am going to combine some of my general, and some of my more recent interests here: my general interest in world literature (and literature, here, does figure, as it were, as one kind of well, if we are compiling ›scenes of visual apprenticeship‹), my interest in the history of connoisseurship (which means also in a more larger sense: in perception, appearance and illusion and so forth), and my interest in the life and times of art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli (1816-1891). Since any time soon I am going to finish a book on Giovanni Morelli that also is meant to develop a new type of biography. A visual biography. A type of biography that focuses on visual apprenticeship. And such apprenticeship certainly never does end as long one lives. And the title of this section here, I am going to use also in my upcoming Morelli-portrait, wherein three larger sections will discuss the visual apprenticeship, the ›Lehrjahre des Sehens‹, of art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli.

Visual Apprenticeship (Second Series)

Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

Gino Capponi

Visual Apprenticeship I –

Gino Capponi

(Picture: storiadifirenze.org)

Bonaventura Genelli, Odysseus sits by the fire as Eumaeus discovers Telemachus at the entrance of his hut

Gino Capponi (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gino_Capponi) is known among historians as having written the first history of Florence, based on modern scholarly principles (published in 1875, in two volumes). Less known is that Capponi was also a father-like mentor to young Giovanni Morelli, art connoisseur to be, and that Capponi managed to write a history of Florence, his hometown, although he had almost completely lost his eyesight.

Capponi had not been born blind. He had travelled in his youth and as a young man; he had seen the artistic riches of his hometown (and he had also criticized, more or less favourably, the work of Giovanni Morelli’s other, his artistic mentor, namely Munich-based artist Bonaventura Genelli: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonaventura_Genelli). Gino Capponi’s eyesight had dramatically deteriorated only later.

In 1841 49 year-old Capponi had travelled to Munich, accompanied by 25 year-old Giovanni Morelli, to see some German eye specialists. But there was nothing that did help. Those who knew and loved Capponi (like Morelli did), could hardly bear to witness the tragic fate of the nobleman with the impressive bass voice (a voice of Menelaos), who, despite his (almost complete) blindness, did serve, nonetheless, his hometown for some time as a politician in 1848, and who could, despite of his almost-blindness, still complete his history of Florence, not to mention many other writings on a variety of topics.

Giovanni Morelli is given credit to have informed those very pages of Capponi’s history of Florence that deal with the artistic heritage of the quintessential Renaissance city. But one may also say that it’s just these very pages, these few pages, that also do reveal, in a yet indirect, but at the same time rather dramatic manner, the tragedy by which Capponi’s life was overshadowed. How to write a history of Florence, the quintessential Renaissance city, if one has lost one’s eyesight?

And one cannot help the impression that Morelli could not, which means: could not endure to be of help in terms of replacing Capponi’s eyes. And maybe we was avoiding the responsibility also for some other reasons, because his own path to modern connoisseurship was also a complicated, and also error-driven one.

Although the young man had turned to become a modern connoisseur, aiming to base his work on scholarly principles as Capponi was aiming to adapt the achievements of the modern (German) school of historical research and writing, namely the principles of Leopold von Ranke (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leopold_von_Ranke) and the Berlin school, the history of Florence by Capponi did not result as a collaboration. And certainly Giovanni Morelli did not like to touch the very subject at all.

But this all was about ›visual apprenticeship‹ on a variety of levels. It was about visual apprenticeship as to the young Gino Capponi’s learning about artistic riches, about those of his hometown and about those abroad. And certainly it was, much later, about a memory of artistic riches, and not to forget, because there was also a Capponi collection (that Morelli, when the collection was to be sold, did assess and sort of also did catalogue), it was also about Capponi’s critical and appreciative gaze at art.

And when young Giovanni Morelli did hear Capponi critize the work of Bonaventura Genelli, it was, in a double way, about the young Giovanni Morelli’s visual apprenticeship. Because his actual mentor in all artistic things had been and also still was: Genelli. And now Morelli heard Capponi speak, only more or less favourably of Genelli.

And of course it was about visual apprenticeship, when Gino Capponi turned to write a modern history of Florence, and someone, since the general ambition was to stick to principles of modern scholarship, had to inform him about new developments in the field of art history, that was developing, most of all, in Germany. And such new developments, if only step by step, and actually only after Capponi had published his history, and after Capponi had died (in 1876), Morelli was about to trigger on his part, by his becoming of being an advocate of scientific connoisseurship. While Capponi worked, for years and decades, on his opus magnum, the history of Florence, the visual apprenticeship of Giovanni Morelli was step by step developing. And this development was also recognized in the house of Gino Capponi, and probably by Capponi himself. But still there was not, there could not be, for tragic reasons (and for human sensitivity), a real cooperation between a historian and nobleman, and a young man, only turning to become, slowly, and step by step, a modern connoisseur.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Count Vronsky

Visual Apprenticeship II –

Count Vronsky

(Picture: deviantart.com)

Kramskoy’s portrait of an unknown woman has become a sort of symbolical portrait of Anna Karenina

Do we feel also compassion for Count Vronsky? Because it is one of the more subtly hidden, but – for us – all the more interesting subplots of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Karenina): Count Vronsky’s giving up, or better: his simple and in the end rather unpretentious stopping of painting (which also could be seen, and the Tolstoy of Anna Karenina does indeed wants us to see it that way, as an expression of visual apprenticeship, of having seen, understood and learned something, if here, the bitter way).

He does not stage his retreat in the end – he simply does stop, Count Vronsky, because he has realized something. And although we don’t know if Count Vronsky would agree with how the narrator of the novel puts it, he has simply learned that, as a painter, Count Vronsky, himself, has nothing to say. Although not being completely incapable, he does manage to have his paintings remotely look similar, compared to other painters’ paintings, but still: he doesn’t seem to see, and subsequently being capable to express something of his own. He does, metaphorically speaking, not work from life, not draw from his own experiences with life, but from what others have experienced and subsequently visually expressed. The portrait of Anna, his lover, he gives up first. And in the end he does not finish his ›medieval‹ painting either. He simply stops. And as a consequence the Italian city is becoming so boring that they both have to leave.

This happens in July of 1874 (Capponi is about to publish his history of Florence; until early June Morelli stays at Rome). Count Vronsky and Anna Karenina had visited Venice, Rome and Naples, and after that, they had moved to this smaller Italian city which Tolstoy does not name to us, to settle for some time in a palace which they are able to rent, a palace with a work by Tintoretto in it that is even mentioned in the German guide.

What happens now (has any cinematic adaption of the novel yet rendered it adequately?), and what makes Vronsky in the end stop painting, is that they are able to visit a Russian painter, living in that unnamed Italian city (if on the other side). A painter, Michailov, who also paints (although he is meant to paint only a portrait of Anny, Anna’s and Vronsky’s daughter) a portrait of Anna. And with this portrait Michailov manages to render Anna’s fair expression (the German translation calls it ›holdseelig‹) to realize Vronsky that this was indeed Anna’s expression that, nonetheless, he, Vronsky, had not come to know before. Not in painting. But more important: nor in real life.

And this is part of the more humiliating experience of realizing that someone else is capable to recognize Anna better (and he has to admit, directly and indirectly by his stopping), better than he is capable of doing so.

First he blames his technique, but this is not what Tolstoy wants us to learn here, staging Vronsky’s bitter visual apprenticeship: it’s because Michailov, who is rather uneducated, does work from life (again speaking metaphorically), he does render what his soul guides him to render in his painting. While the (may we say?) mediocre Vronsky has nothing to say as a painter, not because his technique is mediocre, but because his soul seems to be empty (or only full of conventions, full of what others have found and said and painted, full of one has found, not him).

But here, he somehow still remains likable, at the end of the novel’s chapter 13 of part V. For his not staging his retreat in the end, in one word: for his simply stopping.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Anna Karenina

Visual Apprenticeship III –

Anna Karenina

(Picture: huffingtonpost.com)

(Picture: wordandfilm.com)

Anna Karenina is beautifully introduced by Tolstoy as a character. Or shall we say: her beauty as a character is being introduced? In that Tolstoy says that something abundant was in her, a warmth, an inner light. That even showed if she was eager to keep it back.

And with her husband, whe she returns home, and after meeting Vronsky for the very first time, it is exactly the opposite, or better: it is half the opposite: Because Karenin (here represented, with dignity, by Jude Law) does appear frosty, i.e. without inner warmth to Anna, and more than that: he is being ironical, which means, he actually does have feelings for her, but in being ironical, he is eager not to reveal this feelings for her too obviously, or at best indirectly. And if there is one thing one might say, it is that here is no abundance.

What happens with Anna and her husband on Anna’s return, has, in a double sense to do with visual apprenticeship. It is well known that Anna, on her return, tends to reduce her husband to his ugly ears (and the motif is beautifully discussed here: http://classical-russian-literature.blogspot.ch/2014/12/anna-karenina-karenins-ears.html). She does know that this is not actually fair, and she almost immediately begins to struggle, aiming to correct her own initial judgment.

Tolstoy does not show her as being washed away by her mere feelings (although one might say that there are tides, and for certain moments, it seems, that she does not see more of her husband than his ugly ears). We, as readers, observe her struggling, but she, as well, might be called an observer of this very struggle that she is involved in. Maybe less aware of what’s happening, but aware enough to have her moral conscience to intervene.

She seems to realize, thus, that she is falling into a certain logic, and the interesting question that Tolstoy raises here, might be the question if and to what degree, and under what circumstances, we all might fall or actually do fall into this logic. Of taking the pars pro toto, and especially the negatively seen visual detail, as being representative for the whole human being, and this especially in those moments, when the better part of that particular human being in question does not actually show. In brief: we all run, at times, into this danger of taking the visible (and maybe repulsive) detail for the whole thing. For the partly invisible whole of a person or of a thing, and it seems to be one valuable lesson of visual apprenticeship to keep in mind that there simply might be more, although presently invisible. But the even more important lesson could be that, even if knowing, we will struggle nonetheless. This does not mean that it is reasonable to give up struggling. But the struggle, not to fall into a simplifying logic, is human. And at times we loose.

The other aspect that has to do with visual apprenticeship is that Anna does already know something of her husband, and this knowing seems to be the result of actual learning overtime. Tolstoy does inform us that she knows her husband being a sceptic and a searching man as to philosophy and theology, but being able to take a firm stance in things that do not actually concern him, namely literature, the visual arts, and especially music.

What Anna Karenina is aware of, is, in other words, that knowing to identify and to classify things according to actual conventions, does not necessarily go along with inner participation in such things. The connoisseur who is able to classify without this inner participation does not actually know, or is not actually to be called a connoisseur. And again we encounter this dualism of the visible and the invisible. Competent judgment as to the correct classification of things does not mean anything as to a person’s ability to actually relate to cultural things as a person.

And vice versa: Since, later in the novel, when Anna, being in Italy with Vronsky, and declaring that she was not actually entitled to have an opinion as to a certain painting, she on the one hand acts according to the conventions of society that, for all things, has declared or self-declared experts, but in truth we know, and she also knows that he actually has her own judgment (and is not in need for connoisseurs to teach her how to search and see). There might be, as here, moments when Anna might think, on her part, that it is better not to reveal the actual firmness of her own judgment. But knowing that the actual criteria of knowing something of literature and the arts is inner participation, her seeming modesty, here, does not reveal her character to the full. Although her inner light, her warmth, revealed by her kind tactfullness, might also show here.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Franz Kafka

Visual Apprenticeship IV –

Franz Kafka

Otto Brod and, on the right, Franz Kafka in 1909 as tourists (picture: welt.de)

What did Franz Kafka see, when visiting the Venus de Milo in the Louvre in 1911? Well, he did see something, but he did also observe himself.

The deservedly praised German Kafka-biographer Rainer Stach did manage to do several things extraordinarily well. I would name, in the first place, that Stach did manage to combine an informed appreciation of Kafka’s extraordinary artistic and intellectual capacities with a good deal of common sense. Which means that Stach did accompany, throughout three volumes of a magnificent biography, his biographical object (or subject) with a good deal of common sense. More precise: Underlying to Stach’s biography is not the least the insight that Kafka does, in terms of way of living, does represent an extreme. An extreme in terms of being an observer of oneself, of one’s own life. And this includes the insight that self-awareness is not necessarily of help in terms of being capable to manage one’s own life successfully (given that life means more than being a mere observer). It might be the condition sine qua non if one chooses (but this is probably no choice) to be an artist. But one might also say: the more one does become an observer, and especially an observer of one’s own life, the more one’s actual life reduces (if not to say: diminishes) to mere, and possibly obsessive (self-)observing. And the problem, here, is that self-observing is possibly also a condition sine qua non as to visual apprenticeship.

It is not an episode of which Stach does make something. But even three volumes might not be enough of space to make something of every episode of someone’s life. We may speak about the potential of the genre of visual biography another time (and Kafka-scholar Hartmut Binder, for example, but also Klaus Wagenbach, have done the foundational work as to a Visual Biography of Franz Kafka, in putting together, and also in writing about visual materials that bear on a writer’s life). But the episode that I am speaking of is a visit of Franz Kafka to the Louvre in 1911, with the writer being also able to see the Venus de Milo.

But Kafka did not only see the Venus de Milo. In fact, he did see her, of which we know because, later, he penned down some observations as to seeing her. More precise: In his travel diary and in his memory he went back: he did recall of having seen the Venus de Milo, of being in the presence of the Venus de Milo. And in working through, and in penning down his observation, namely, he did also and again, as he was in the habit, observe himself, here: as being in the presence of the Venus de Milo. Because what he did tell to himself (and since his diaries have also been published also to us), is that he made a forced remark, being in the presence of the Venus de Milo. And it must not even concern us here, what exactly this ›forced remark‹ of Franz Kafka was, when being in the presence of the Venus de Milo. The thing is that visual apprenticeship can also mean, and this is what we do become aware of here, to look back as to how one did behave when being in the presence of a work of art, and possibly also to look forward, namely, as to a possibly making progress in terms of how to look of art.

And this is exactly what Franz Kafka did also do, judging from his diary. Because he did not only muse upon his forced remark, but also upon some true remarks or observations that he also did recall when writing into his travel diary. Only that he says that he would be in need of a good reproduction, or even a model of the Venus de Milo, to recall (and possibly check) his true remarks. And this, a going back as well as a possible going and thinking farther, one might say, is obsessive self-observation, but also an obsessive (i.e. potentially also risky) take on visual apprenticeship. It is observing, if one’s observations that one does observe anew when writing a diary do stand against anew observing (and observer of all this are we, ourselves). And this is a way, certainly, to make progress in one’s visual apprenticeship, but it is also a possible way of becoming an obsessive mere observer. Which, while it certainly can be a good thing, cannot be a good thing only, if the quality of one’s observing has also something to do with living, and not only in terms of being an observer. But perhaps also in terms of common sense (and aggrandisement of common sense by living).

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

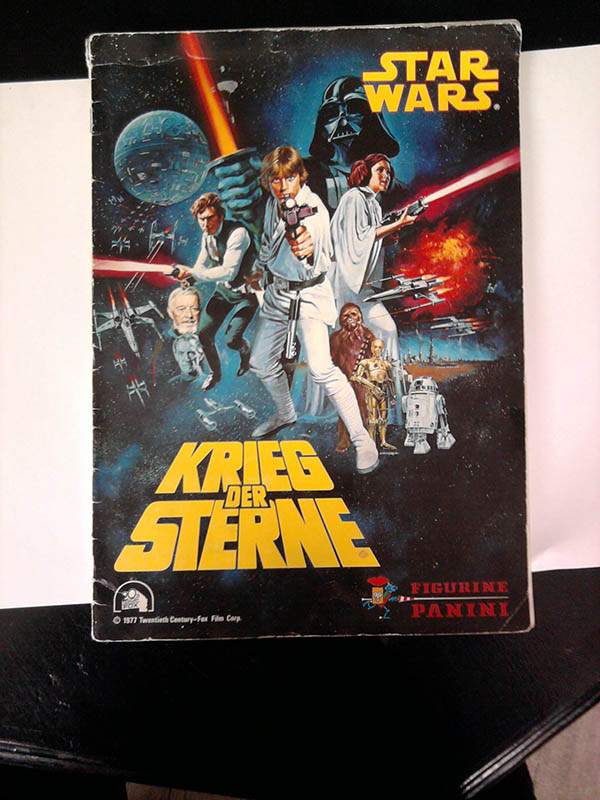

Luke Skywalker

Visual Apprenticeship V –

Luke Skywalker

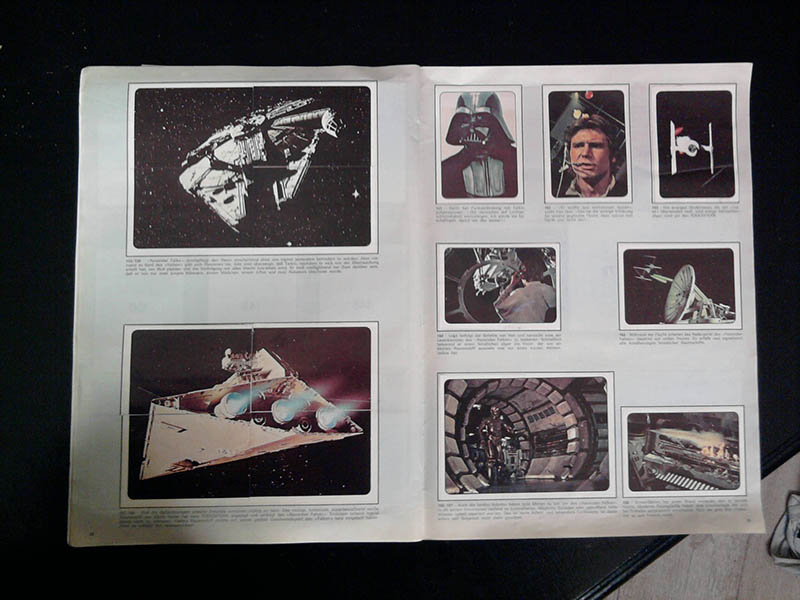

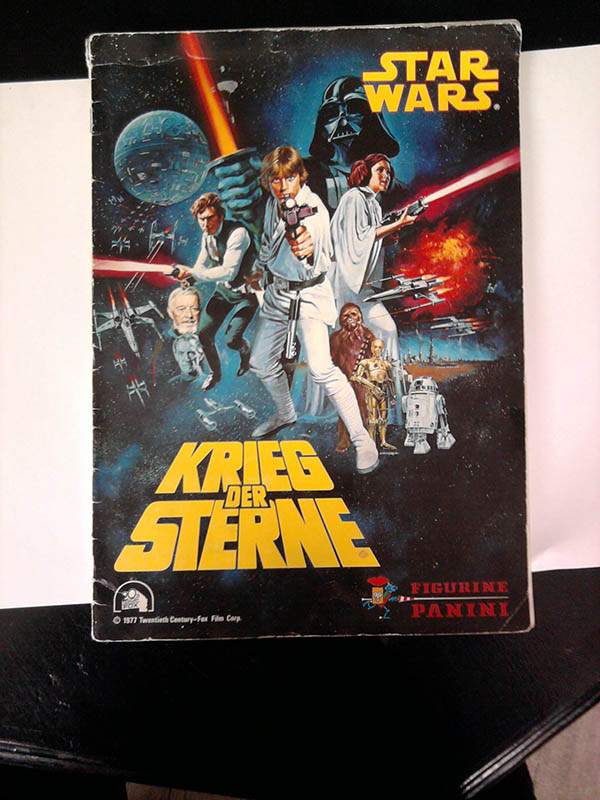

(Picture: der-lustige-modellbauer.com)

(Picture: der-lustige-modellbauer.com)

My first cinematic experience was E.T. in 1982, which is a fact. It cannot be doubted. The extra terrestrials were coming as botanists to the Earth. But long beforehand this first cinematic experience I know that I knew something of merchandising (of which the extra terrestrials certainly had never heard of). And this seems to be worth exploring. By a kind of looking back, a kind of, at least of trying to look back at a former looking at things – the way one, the way I did look at things when being a six-year-old child. Ready for experiences in looking. Reading. And: In collecting.

Because my first encounter with the world of Star Wars, in 1977, was a Star Wars album of collector cards. I know I had this album, although I don’t seem to have it anymore. But I know it because, stored in my memory, I have this recollection that some pictures were still missing. I had the album, but I had it not completed.

And I seem to know even today which picture, for example, was missing. It was the right upper corner of the large picture of the Millennium Falcon, the spaceship piloted by Han Solo and Chewbacca (a ship whose design, I am reading now on the Internet, had been inspired by a hamburger).

And there was supposed to be a picture in the album of collector cards, showing the Millennium Falcon, a picture made of four pictures. But in my album the right upper picture of the Millennium Falcon was missing. And I believe to recall the dark urge to have this album completed. The rage of a child because of one picture missing (and certainly other pictures missing too, but I do not recall them as being missed).

Probably the one picture was still missing when I had lost interest in that Star Wars album. Since it has not survived I must have lost interest in that album sometime, and I doubt that the album had been completed. Completed as the one that I have now found on the Internet. With all the pictures. And if I am thinking back – how weird does it seem that today anything can be found on the web that once was missing. Did anyone imagine then, did anyone tell a six-year-old child that some day, when the child would have grown up, that everything, every picture could be found? That everything, some day, would only wait to be seen? These weren’t the rules then, and I wonder what the rules will be, if, let’s say, 35 years from now on have passed. From now, when everything seems already to be there. For free. To be seen. And unveiled. (But what happens in the imagination goes, probably by definition, beyond that.)

The charm of that album by the way was a certain literary charm. The charm of a picture book telling a story, but leaving much – between the lines, between the pages, between the single pictures – to the imagination. The story of Luke Skywalker – it is the story of the classic hero, the story of a symbolic growing up, of taking one’s challenge, and to become a man and a hero (not to forget: a symbol of all that is good in the galaxy). And the Star Wars album had the storyline, but only windows to look into that film: the single pictures with their accompanying texts. And there was a clear fence between the beholder/reader and the space wherein this story was situated. On the other side of that fence. (And the missing of some of these windows, as we have seen, was probably adding not only interest to that story, but perhaps also interesting ambiguities to the story and its, well, look, at least as to that Star Wars episode, which is organized according to a very clear distinction between good and evil, and does, as it seems to me, although it uses the color white also as symbolizing evil, not foreshadow that certain passages of certain characters from black to white and back remain possible.

As to E. T. – I do recall that vague feeling that everyone felt that having seen that movie was a must. As with the Star Wars album – someone had managed to implement the feeling into everyone’s mind that one had not only to see that movie, but that the experience of having it seen was socially necessary and wanted. This urge had been implemented into everyone, had organized it, seemingly, all by itself into everyone, as someone, or it, had implemented the dark urge into a child’s mind of wanting to have the Star Wars pictures. Two types of being affected by the mechanism of marketing and by the dynamics of all members of society’s mutual observing and comparing, of which the extra terrestrials (and also Luke Skywalker) certainly did not know of. The wish to have something for its own sake (as for the album: not because the others had it, I believe), and the wish to share an experience, because everyone was already sharing that experience (or the fear not being able to share and to be excluded; and the fear of not having the last picture and to remain excluded from the experience of having it).

Both experiences, in being first experiences, have probably left their mark, and not only in shape of memories left. Because the collecting of Star Wars collector cards did not result with me becoming a collector at all. What remained, probably after the experience had repeated, was that I lost interest in that kind of collecting rather completely (but not in reading, nor in looking, or in other ways of collecting). Somehow it did result in that I did unlearn to collect, if collecting meant to have completed what someone, for whatever reason, had defined as the must-have-pattern and number of pictures. And if I am looking at it from this side, the prize for these collectors cards and for this album was worth paying (as I am writing, by the way, it does occur to me that the album was actually given away for free at the shop where we did buy the cards; how subtle! and I am recalling this only while writing, the actual bait… with the storyline, but without the storyline pictured).

In sum: While one does learn something about looking, like for example about the way a story can be told with using words and images (and also much of free space), one does also unlearn things like for example the wanting to have it all (because the free space has its own worth, and it is even for free, as the whole album). Maybe to the chagrin of merchandising departments – it simply doesn’t seem necessary to have it all, to the imagination to enfold that story which, if one does grow up with fairy tales, already might have been familiar anyway. It does not pay (on the contrary), nor it is worthwhile to have it all.

But why did it bother then. Not to have that one right upper corner of the hamburger-like spaceship picture? Was it simply a raw hunger for pictures and for a story, that wanted to be fed? I don’t know, but somehow it has turned more into a hunger for an interesting and also intense experience (and looking back also at experiences, sensual and intellectual). Experiences that are not imposed upon me by just one director. Or by the directors of merchandising. Or collecting. And it might have been a Star Wars album – at the beginning of all that.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Rémy Zaugg

Visual Apprenticeship VI –

Rémy Zaugg

kein Bild vorhanden

(Picture: keines/none)

kein Bild im Internet vorhanden

(Picture: keines/none)

Die Kunst von Rémy Zaugg – gilt sie als streng und spröde?

Machen wir den Test aufs Exempel: ein vierteiliges Text-Bild aus dem Zentrum Paul Klee. Gelesen mit Wolfgang Herrndorf. Und wir fassen uns kurz.

In den Fragmenten, die Wolfgang Herrndorfs Notaten Arbeit und Struktur (in der Buchausgabe) beigegeben sind, heisst es (in Nr. 10, S. 438): »Fünf von sieben Frauen, in die ich in meinem Leben verliebt war, haben es nicht erfahren.« Als Teil einer fragmentarischen finalen Lebensbilanz erscheint diese Aussage, and man hält innerlich inne, zögert, um letztlich doch zu fragen: Kann man sich denn dessen sicher sein?

Vielleicht haben diese Frauen sehr wohl etwas registriert, etwas, das keinen sprachlichen Ausdruck gefunden haben mag, aber vielleicht in einem schwer ruhenden Blick Ausdruck gefunden hat. Was ungesagt geblieben sein mag – muss es denn auch unsichtbar geblieben sein?

Der 2005 verstorbene Künstler Rémy Zaugg hat Text-Bilder erschaffen. Eine Reproduktion des Werks, um das es mir geht, hat sich, zumindest im Internet, nicht gefunden, aber eine Vorstellung vermittelt hatte sich mir aus einem Buch, und es sind, auf den ersten Blick vielleicht unscheinbare, aber, wie mir scheint, doch lichterfüllte Tafeln (weisse Schrift auf hellgrauem Grund): um ein vierteiliges Text-Bild handelt es sich, und man könnte von einer Bewegung sprechen, die vom ersten bis hin zum letzten Bild inszeniert wird. Eine Gedankenbewegung vielleicht. Aber vielleicht handelt es sich eher um eine Reihung von Gedanken und von leeren Zwischenräumen, Pausen, eine Reihe, die vom Betrachter nachzugehen ist, will er versuchen, das Werk nachzuvollziehen – was sich hier mit einer Art Nachschöpfung vollzieht, die nicht bloss nachvollzieht, sondern auch eingeladen ist, das Werk mit eigenen Gedanken und Gefühlen aufzuladen und zu konfrontieren. So dass ein Betrachter auch eingeladen ist, das Werk fortzuführen. Gedanklich. Was wir hier tun. (Wobei das Werk, wie wir gleich sehen werden, einen Impuls zurückgibt, und zeigt, dass es Teil des Betrachters, seiner Gedankenwelt, geworden ist).

»ICH SCHLIESSE DIE AUGEN UND ICH BIN UNSICHTBAR«, heisst es auf der ersten Tafel. Evoziert wird hier, vielleicht, kindliche Magie: die Vorstellung, gleich mit zu verschwinden, wenn sich die eigenen Augen willentlich (ver)schliessen und die Sicht auf die Welt, das Sehen gleichsam eingestellt ist, umgestellt auf eine Sicht nach innen, und der Sehende innehält und – vielleicht – denkt und träumt.

Und mit Herrndorf gelesen, könnte man denken: Meine Augen schliessen sich, und so kann mein Blick nicht mehr gelesen werden. Mein Ich, vielleicht mein liebendes Ich, bleibt unsichtbar. Von meiner Liebe wird niemand erfahren, sie behält sich für sich, die Liebe, wird unsichtbar, geht mit mir auch, wenn ich gehe, für immer zugrunde. Das kindliche Wissen, im Grunde, ist wahr. Es weiss bereits (oder besser: noch) vom Blick.

»ICH SAH DAS UNSICHTBARE IN MEINEN AUGEN«, heisst es auf der zweiten Tafel. Gedanklich kann sich der nach innen sehende Betrachter aufraffen und eine ungewohnte Beobachterposition einnehmen: Sich selbst sehend, als Liebenden, dessen Augen liebend sind, aber geschlossen, sich nicht veräussernd, nicht sich offenbarend oder verschenkend. In bzw. mit einem Blick.

»ICH SAH WAS ICH UNSICHTBAR

GLAUBTE« bedarf keines Kommentars. In eines anderen Menschen Augen spielt sich ab, wovon der eine Mensch, augrund seines eigenen inneren Gesprächs, wiewohl vielleicht zweifelnd, weiss (im Zwischenraum zwischen Tafel zwei und drei hat sich etwas zugetragen, Augen haben sich geöffnet, eine Erkenntnis, vielleicht, vermittelt): Unsichtbares zeigte sich (und eine theologische wie eine säkulare Lesart scheint möglich).

»ICH SAH ALL DAS. UND DAS SAH MAN IN MEINEN AUGEN.« schliesst die Reihung von vier Gedanken. Nicht Strenge oder Sprödigkeit scheint auf, was die Gedanken selbst angeht. Vielmehr Fülle, Hoffnung und die Möglichkeit menschlicher Zwiesprache (und Zwiesprache auch mit dem Unermesslichen): Leben. Und kurz gefasst: je spröder, reduzierter die Form hier, desto mehr Fülle weiss sie aufzunehmen, und desto intensiver wird diese Fülle sich auch zu vermitteln, während sich das Kunstwerk gleichsam zurückzieht (und jedenfalls nicht weiter aufdrängt). Form, reine, allgemeine, aber nicht abstrakte Form, die von jedem Menschen anders erfühlt und erfüllt wird, wenn er als Mensch, als Individuum, persönliche Gedanken und Gefühle hineingibt. Und damit auch anzeigt, das er vom Unsichtbaren, nämlich seinem Denken und Fühlen gebraucht macht, und zuletzt auch, vielleicht, von seinem Denken und Fühlen weiss, weil das Kunstwerk ihm dieses Wissen zurückgibt: in seinem stummen, eindringlich-verhaltenen, doch sichtbaren (und nur in Pausen, Zwischenräumen unsichtbaren) Impuls macht es den Blick und was ihm zugrunde liegt, die Schöpfung, bewusst.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Luke Skywalker (II)

Visual Apprenticeship VII –

Luke Skywalker (II)

(Picture: der-lustige-modellbauer.com)

(Picture: hurstvillegolf.com.au)

Luke Skywalker, der sich an Bord des Millennium Falcon befindet, Luke Skywalker, der Held des global verbreitenen Bildungsromans Star Wars, übt sich im Verteidigungskampf. Gleich wird die Anweisung des Mentors folgen, nun einen Helm überzustülpen und blind weiter zu kämpfen.

Was hier erprobt bzw. durchgespielt wird, ist die Position extremer Skepsis gegenüber jeder Form von Sichtbarkeit und Augenschein, und gleichzeitig das Einüben von (blindem) Selbstvertrauen, oder anders gewendet: von Vertrauen in die ›Macht‹ (die das Selbst gleichsam durchpulst und diesem Selbst im Kampf Leitung zuteil werden lässt).

Im Hintergrund der skeptische Han Solo, der selbstredend nicht ganz einverstanden ist, und hier die Gegenposition einnimmt: besser auf Nummer sicher gehen, auf den Augenschein nicht ganz verzichten, wenn es denn nicht notwendig ist.

Das Finale des Films wird ihm recht geben, so wie das Finale zugleich auch Lukes Intuition recht geben wird. Und der interessante Punkt ist der, dass die beiden Figuren, Han Solo und Luke Skywalker, in den frühesten Entwurfsskizzen des Star Wars-Autors, wenn nicht eine Person gewesen sind, so doch zwei komplementäre Seiten einer Person repräsentieren, nämlich zwei Seiten des Autors George Lucas. Man vergleiche die frühe Lucas-Biographie Sternenimperium von Dale Pollock: »Der Charakter [Luke Skywalker] hatte viel Ähnlichkeit mit Lucas’ eigenem antagonistischem Temperament: der unschuldige, idealistische und naive Typ, verbunden mit dem zynischen Pessimisten (der wird später zu Han Solo).« (S. 92)

Erst später, nehmen wir zur Kenntnis, spaltete sich die Skepsis ab.

Fazit: die obige Szene hat zur Voraussetzung, dass ein idealistischer, formbarer Held vorhanden ist, der noch nicht Skepsis oder zynischen Pessimismus verinnerlicht hat. Denn nur der reine Idealismus lässt sich auf blinden Verteidigungskampf ein. Vertrauend auf Gefühl, Intuition, innere Stimme. Und misstrauend, wenn auch nur im Rahmen eines Übungskampfes, dem reinen Augenschein.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Nick Carraway

Visual Apprenticeship VIII –

Nick Carraway

(Picture: premiere.fr)

(Picture: 3.bp.blogspot.com )

Der eigentliche Held im Roman Der grosse Gatsby heisst Nick Carraway (seines Zeichens Erzähler des Romans Der grosse Gatsby).

Man sehe nur (im Film mit Robert Redford), wie er sich eine Mahlzeit bereitet hat, ein grosses Glas Bier steht da, und wahrscheinlich besteht die Mahlzeit weitgehend aus einem Steak); und er sitzt auf seiner Veranda, die zu einer Hütte gehört, die er für 80 Dollar gemietet hat (dort wo eigentlich nur die Reichen wohnen), und harrt der Dinge, die da kommen mögen.

Und die Dinge kommen auch. Die Geschichte des grossen Gatsby, des Träumers, Liebenden und Strebenden, den die Verhältnisse zermalmen, geht durch ihn hindurch, nimmt ihn mit (im doppelten Sinne). Aber was wäre, wenn wir uns einmal vorstellten, dass es Gatsby gar nie gegeben habe. Dass die Geschichte des Grossen Gatsby bloss den Träumen des Nick Carraway entsprang. Der kein Gatsby war, aber die Weisheit in sich hatte, – im wachen Träumen – ein Gatsby zu sein, einen Gatsby zu erfinden, und zuletzt auch zu sehen, was es kostete, ein Gatsby zu sein (nämlich zermalmt zu werden vom Schicksal). Und dass es besser war, kein Gatsby zu sein, sondern bloss ein Nick Carraway.

Gatsby, also, hat es gar nie gegeben. Aber wir wollen nicht zu weit gehen.

Es mag hier ausreichen, darauf hinzuweisen, dass es Nick Carraway, dem mehr oder minder zurückhaltenden Beobachter, der vielleicht auch darunter leidet, mehrheitlich bloss Beobachter zu sein, dass es Nick Carraway also nicht an Weisheit mangelt.

Zum Beispiel bemerkt er (zu Beginn des Romans), dass es erfolgversprechender sei, das Leben bloss immer durch in Fenster hindurch zu betrachten. Und nicht durch mehrere. Er weiss das (oder scheint es zu wissen), und handelt doch (zum Ende des Romans) entgegen dieser Weisheit.

Denn er gibt Tom Buchanan doch die Hand. Entgegen seiner Absicht, es eigentlich nicht zu tun. Weil sich Tom Buchanan in unverzeichlicher Weise schuldig (vielleicht nicht wissentlich schuldig, aber schuldig) gemacht hat. Dass es den Grossen Gatsby zermalmt hat. Aber Tom Buchanan schien, das ist eben die andere Weisheit des Nick Carraway, sein Verhalten vollkommen gerechtfertigt. Und Nick Carraway, in einem symbolischen Sinne versöhnungsbereit, gibt ihm die Hand.

Die Wege trennen sich. Und komplementäre, sich ergänzende Weisheiten, kleine Weisheiten, nehmen wir mit.

Zum Beispiel die Tatsache, das eine Fenster einmal beiseite gelassen, durch das man das Leben betrachten sollte, wenn man es auf Erfolg im Leben anlegt, zum Beispiel die Tatsache, dass sich Nick Carraway, auf der Fifth Avenue daherkommend wohl in dem Schaufenster des Juwelierladens, in den Tom gerade hineingehen will, gespiegelt hat. So dass Tom ihn sieht. Der Roman führt das nicht aus. Aber Nick, der Erzähler, weiss es (denn er hat es selbst erfahren) – und er weiss, dass ein Prinzip gut ist (nämlich nicht gesehen zu werden), dass dies aber, vielleicht glücklicherweise, nicht durchzuhalten ist. So dass es zu einer Versöhnung kommt. Einer symbolischen Versöhnung bloss, aber eben auch zu einem Bild. Einem Bild, in dem sich Tom, wie er nun einmal ist, noch einmal darstellt (gespiegelt in den Augen des Nick). So dass wir den Roman verlassen können. Wissend, dass er eigentliche Held des Roman Nick Carraway sei.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Angelica Sedara

Visual Apprenticeship IX –

Angelica Sedara

(Picture: goodreads.com)

(Picture: frenf.it )

One particular interesting scene or better image (because it is only a fragment of a scene) of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel Il Gattopardo that did not find its way into the movie by Luchino Visconti is the scene wherin Angelica gets instructed by Tancredi and by the old-nobility Falconeri family how to be blasé. Because we (snobbily) expect here that everyone has read that novel anyway, it might be enough to simply state that – on the level of the novel – Angelica does brilliantly succeed (occasionally they have to stop her, when »the ship« again »gets going« all by itself). All of her life an, as the author informs us, undeserved reputation of being an expert of artistic things was hers.

Brilliant. It goes without saying that the Gattopardo himself, Prince Salina, is, as the author shows us, occasionally very blasé. And it is an interesting question, if not the author himself, in making fun of his both main characters of being blasé, is the most blasé of all, but here things get very complicated. Because, unlike the Prince Salina, the author, (Prince) Tomasi di Lampedusa – whose friend Corrado Fatta published, after Tomasi had already died, a book called Du Snobisme which is also dedicated to Tomasi – knows, if he is being blasé and he is obviously capable of displaying irony.

Anyway. We do not have pictures from that movie to analyse someone being taught to be blasé. But we have the pictures above and we keep in mind that a) it is a woman who is being successfully instructed and b) the scene (or the image) from the novel opens another perspective on the history of connoisseurship for us and not least on its visual dimension.

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

Mark Twain

Visual Apprenticeship X –

Mark Twain

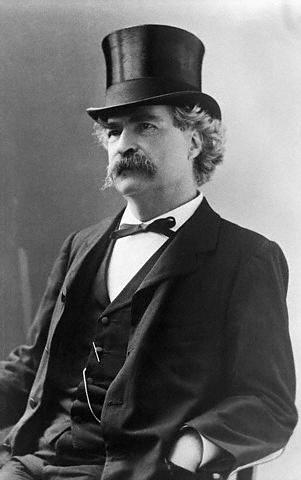

(Picture: twainquotes.com)

(Picture: travelsouth.usa)

American writer Mark Twain, mostly known for humoristic stories, but also a contemporary of art connoisseur Giovanni Morelli (who is all too little known for humoristic stories), had also something to say on art connoisseurship.

For example in his A Tramp Abroad of 1880.

What I do find here is a very valuable, if humoristic, or: very valuable just because of being humoristic, definition of what in the context of attributional studies one would call a unique property.

And since I am going to write on this topic any time soon, referring also to Twain and to this passage, I am only quoting the passage here. We have followed the tramp to Germany where one has instructed him in painting and drawing, and now one does speak about his paintings, about his unique style:

»They said there was a marked individuality about my style, insomuch that if I ever painted the commonest type of a dog, I should be sure to throw a something into the aspect of that dog which would keep him from being mistaken for the creation of any other artist.« (vol. 1, chapter 11, p. 88)

In other words: a something, found only in one and only one class of objects, the objects created by the tramp, and this, on an abstract level, one may call a unique property, and in the context of attributional studies it is most valuable to know about such unique marks.

(Apart from this definition, Twain goes on, in his inimitable humoristic way, to provide us with some sceptical thoughts about this ›marked individuality‹, and perhaps also about the myth of the unique property. But this I am going to elaborate in a paper, meant for the second issue of the The Hague Authentication in Art congress of 2016.)

Visual Apprenticeship (Second Series)

Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

© DS