M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

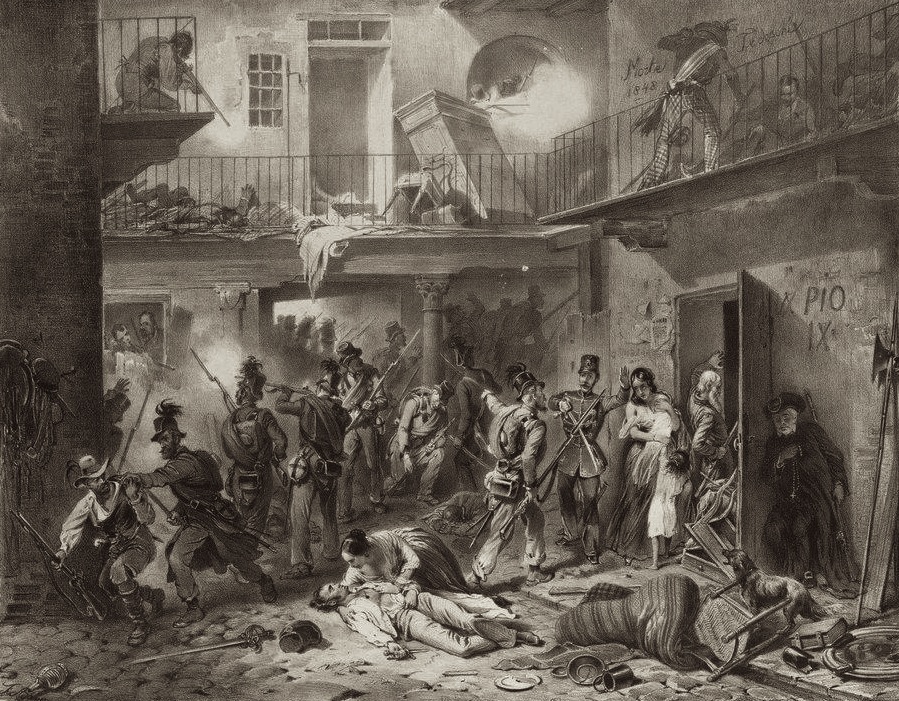

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY Visual Apprenticeship I  |

When Giovanni Morelli was forty years old, he started to collect works of art. This might also be interpreted as a kind of turning point in his life, since up to the year of 1856 little had pointed to his – rather late in his life – becoming a connoisseur of art, although the visual arts had also, next to many other things, ranged among his interests. Thus, the biographical panorama that leads through the first forty years of his life, up to the year of 1856, shows in a way the ›other‹ Morelli. It shows with Morelli studying, with Morelli discovering his literary ambition, with Morelli travelling and experiencing nature, with Morelli experiencing war times, and last but not least: with Morelli discovering the roles one has to play in society (and politics), the necessary backdrop to his later becoming a connoisseur of art, and of his becoming a personality that some who knew him were inclined to call also an expert as to human nature and a man of the world.

And a section that one may call also ›The Young Morelli‹ shows a Johann Morell/Giovanni Morelli, conversing with German and French 19th century artists (and connoisseurs), which also might be interpreted as a necessary counterpoint to his later developing his expertise for Renaissance painting and drawing and (to some degree) also for Dutch painting, since, especially as a collector, he did not at all dismiss all other periods of art, even if he was inclined to speak of the Renaissance period as the ›Golden Age‹.

VISUAL APPRENTICESHIP I:

(ONE) A LION’S BLADEBONE AND A REAL CONNOISSEUR’S EYE

(TWO) NATURE, LANDSCAPE AND ONE’S HOME COUNTRY

(THREE) HUMAN ROLES IN WAR AND PEACE TIME, HUMAN MASKS

(FOUR) SECLUSION, INTROSPECTION AND COLLECTING![]()

ONE) A LION’S BLADEBONE AND A REAL CONNOISSEUR’S EYE

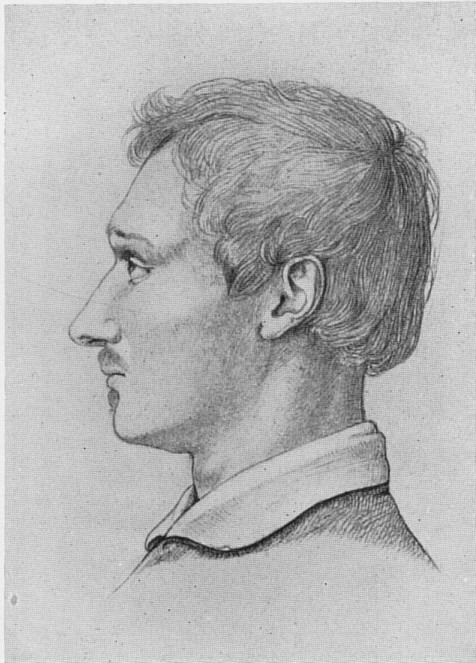

21-year-old Giovanni Morelli as drawn

by Bonaventura Genelli in 1837

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 114)

›Not a human soul I have here, that I could share a thought with (except my scientific matters) – not to mention someone who would, like you do, encourage me to all good and beautiful and who would instruct me.‹

»Keinen Menschen hab’ ich hier, dem ich, ausser meine wissenschaftlichen Angelegenheiten, einen Gedanken mitheilen könnte – geschweige denn einen, der mich, wie Sie, zu allem Guten u Schönen aufmunterte u mich belehrte.«

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 14 June 1838; from Berlin)

Bonaventura Genelli (1798-1868)

(picture: stadtmuseum.bayerische-landesbibliothek-online.de)

GENELLI’S TAKING A WALK: AN INTRODUCTION

Every now and then it happened that Munich-based artist Bonaventura Genelli stopped working all of a sudden. Not because of being tired of working (although he lived under rather dire circumstances at Munich with his family, and without a patron). But only due to a very welcome arriving of a letter. A letter by his dear friend Johann Morell, sent from Erlangen, Berlin or Paris, or elsewhere, and later mainly from Italy. From his friend, who was capable of producing this kind of overwhelmingly hilarious and often very funny letter, this kind of in any way delightening and heart-warming letter. And all of a sudden Genelli could not go on working anymore, but had to go out to take a stroll. And somewhere, out in the green, or in the city of Munich (but rather not in the English garden, where one might encounter rivals or enemies), somewhere he would stop: to take that letter out of his pocket and read it, decipher it as good as he could (since Morelli’s handwriting was not particularly easy to read). And he would read it again, to make the most of it, to savour the letter as much as he could savour it, because, if there was something to delighten Genelli, it was a letter by his dear friend Morell.(1)

Who had left Munich all too soon in 1837, to come back once again, but only briefly, in 1841. And after this last short visit this remarkable friendship between the artist and the connoisseur of art to-be, was to remain the correspondence of two pen friends. To the chagrin of both, but with Genelli suffering more from it, while the friendship, in fact, was of existential importance for both of them. A friendship between a somewhat older mentor (Genelli) and a student (Morelli), between someone more inclined to write (Morelli) and someone being less friend of writing letters (Genelli), and it was the friendship between someone who had to stay at Munich and someone who could and had to return to Italy, to further live in Italy. Away from his friend, but keeping, in his heart, his warm affection, throughout of his life, that he had for his dear Munich friend.

18-year-old Giovanni Morelli in 1834,

as seen by Wilhelm von Kaulbach

(source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 70)

Bonaventura Genelli was the one man that Morelli did allow to criticize him, since he had accepted (or even chosen) Genelli as a mentor. And if Genelli did indeed criticize Morelli, as it was occasionally the case, for example for Morelli being all too undecided, all to inclined to leisure also, all too lazy, Morelli did not wrangle (as it was otherwise the case, for example if Morelli was criticized by one of the Frizzoni brothers), but accepted the criticism without (his otherwise characterisic) muttering, if not to speak of (also characteristic) energetic counterattacks.(2)

Because in Genelli he had found that one man that he thought of as a real teacher, not only in all affairs related to art, but also as to how to look at life in general. And specifically Morelli appreciated Genelli as the one man who also really responded to his fancies, ideas and projects.(3) His literary ideas, in the first place, since literature, namely Morelli’s first satirical piece, the Balvi magnus of 1836, had been the actual reason that the two men (Morelli then being 20, and Genelli being 38) had met;(4) and Genelli was to become the one to encourage Morelli, to criticize and encourage him in all his efforts. And in that particularly Morelli did accept and love Genelli as a friend, beside that he did appreciate Genelli’s wayward art and character.

We are fortunate to have that correpondence, if unfortunately not entirely, since many letters seem to be lost. But we are lucky because of the specific and natural arrangement that was the outcome of this friendship: with Morelli writing, and writing letters that actually were meant to be, in some sense, literary writings, and with Genelli commenting about Morelli’s doings and about his lively descriptions of many a thing, scenario or person.

And since indeed many of Morelli’s letters contain graphic descriptions, since Morelli did try to show Genelli graphically what he had seen or experienced, we dispose of a valuable source as to the young Giovanni Morelli’s way of looking. That manifests in these descriptions, while Genelli’s comments serve us as valuable counterpoints and provide us with extra informations.

The roles in this correpondence of two pen friends were and remained also relatively fixed. We see two friends, speaking not only of how to see art, but also of how to see life, and about how to deal with life. From the perspective of a poorly living artist at Munich, and a moderately well-to-do Italian student of Swiss descent who had studied at Munich, and from the beginning had been also eager to support Genelli as good as he could; Genelli whom Morelli regarded as being a humiliated genius, a genius being too proud to offer his services to the ruling taste (and rightly so!).(5) And Morelli did much, not only to encourage Genelli and have him feel that he was appreciated, but also in recommending Genelli to potential solvent clients, and namely also to his Bergamo friends Giovanni and Federico Frizzoni, to whom he described Genelli also as follows:

›It is a real anguish to me to see this great genius slashing his way through life that meagrely. Genelli is an uncommon appearance – yet unfortunately recognized only by few. His external magnificent guise corresponds fully with his mind, which does not show a hunch anywhere, as it is common as regards to people which are shining, but as he does have his art taped, he has life taped to the most profound abysses, and he does look at things as they are, not finding, for instance, in every milk pot, as Görres and Friedrich Schlegel (do), the Holy Trinity.‹

························································································································································································································

»Es ist mir eine wahre Pein, dieses grosse Genie sich so kümmerlich durchs Leben schlagen zu sehen. Genelli ist eine seltene Erscheinung – doch leider nur von wenigen erkannt. Seine äussere herrliche Gestalt entspricht ganz seinem Geiste, der nicht etwa, wie das gewöhnlich bei Luminibus der Fall ist, irgendwo hinaus einen Buckel hat, sondern wie seine Kunst, so durchschaut er auch das Leben bis in seine tiefsten Abgründe und sieht die Dinge an, wie sie sind, und findet nicht etwa, wie Görres und Friedrich Schlegel, in einem Milchtopfe die Dreieinigkeit.«(6)

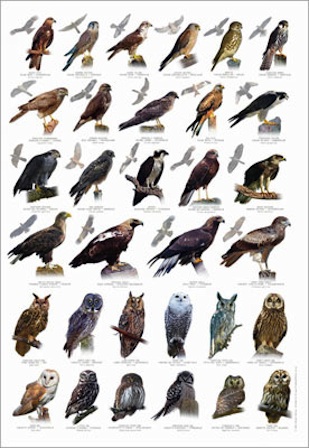

(Picture: wikimedia.org)

When in 1837 Morelli had been still working for his Munich professor Ignaz Döllinger, Genelli must have visited Morelli also at work. Since on such an occasion Morelli must have presented Genelli with an unusual gift: a plaster cast, taken from the bladebone of a lion; and probably Morelli had also been working on a whole lion’s skeleton.(7) We have to keep this in mind, if we now turn to look at a first example, taken from one letter, an example of how young Giovanni Morelli did look at things. At Paris, at a local theatre, and among other animals also at a mighty African lion.

*

AN AMERICAN NAMED VAN AMBURGH AND HIS CATS

Only specialists for 19th century popular culture would probably know his name today – but Isaac A. Van Amburgh (1811-1865) was, at his day, the wild animal trainer of his day,(8) a public figure, fascinating personalities as diverse as American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, Queen Victoria (who had just ascended to the throne in 1837), and last but not least young art connoisseur-to-be Giovanni Morelli.

What better opportunity do we have to look at the way of looking of 23-year-old Morelli, who, in Paris in 1839, got to see Van Amburgh’s show? Since we do not only dispose of a letter by Morelli describing, to his friend Genelli, what he had seen, but also a context of a world-wide popularity of this particular animal trainer, and a context of a many pair of eyes, being also fascinated, as Morelli was, by what Van Amburgh was doing with and amidst his animals. Some pairs of eyes (that of writer Nathaniel Hawthorne) also sensing the atmosphere of an audience watching,(9) others inclined to have what they did see also again being represented, and maybe anew and differentely represented and interpreted – in painting.

But here, we may start off with hearing, and subsequently discussing, what young Giovanni Morelli had to say. Since what he had to say was meant to show Genelli, in words, what he had seen; and this, certainly unintentionally, does nonetheless also serve us, who are, as Genelli, not in the position to verify in the flesh what Morelli had seen, to see how he did see (and how he liked others to hear about what he had seen and how he did see):

›Presently a certain Mr. van Amburgh, an American, baffles the audience due to his tamed cats, and indeed one has to open wide one’s eyes, if one does see this man handling his beasts. The performance takes place in one of the local theatres. One even has composed a piece (of music) which, though, is beneath contempt – although certainly, as to this rare appearance, something decent could be done. Also the whole arrangement is pathetic. Because the curtain does open, and you do see an enormous cage, separated in two by an interior wall. In one (cage) there are two big Asian lions, male and female, a Bengal tiger and 3 leopards. In the other the most beautiful animal I have ever seen, an African lion with a tremendous black crest, a most rare species, further an marvelous tiger and a panther. Van Amburgh now enters the cage, the animals jump up on him, he puts his head into the lion’s throat etc. – in brief, he does the most foolhearted that only one can do, so that one is inclined to believe in the story of Daniel in the Babylonian lion’s den. – The most beautiful, though, without doubt, is (occurs), if he does tease the big lion. This mighty animal does vertically raise at the bars, and with terrible roaring opens his enormous jaws, in that with one paw it does strike at him, – whereas van Amburgh solely raises his hand, with the lion todying into the corner – and he goes on to lay down between tiger and lion and does play with them. Then he does bring a sheep – tiger and panther get ready to jump – van Amburgh, fixedly, has an eye on them. The lion does allow the sheep to lick him and hardly does take notice. The tiger does roar and his eye is gleaming terribly, and yet he does not dare to wrangle. I still do believe, by the way, that the foolhearted man will lose his life, when performing such a maneuver. The groupings and postures of this magnificent animals altogether are often charming, namely if the marvellous leopards raise at the grid like supporters, grinning at each other [snarlingly]. If one would imagine this image woven into a clever drama, add a beautiful decor to that, and anyway the bars arranged differently, with beautiful music (since this has to be part of it, always) – given the eerie silence in the whole theatre, that should be delightful.‹

························································································································································································································

»[…]. Gegenwärtig setzt ein gewisser Herr van Amburgh, ein Amerikaner, durch seine gezähmten Katzen das Publikum in Erstaunen, und in der Tat muss man die Augen aufreissen, wenn man diesen Menschen mit seinen Bestien hantieren sieht. Die Vorstellung geht auf einem der hiesigen Theater vor sich. Man hat sogar ein Stück dafür komponiert, das aber unter aller Kritik ist – obwohl sich bestimmt zu dieser seltenen Erscheinung etwas Ordentliches machen liesse. Auch ist das ganze Arrangement erbärmlich. Der Vorhang geht nämlich auf u. Sie sehn einen ungeheuren Käfig, der durch eine Zwischenwand in zwei geschieden ist. In dem einen befinden sich zwei grosse asiatische Löwen, Männchen u Weibchen, ein bengalischer Tiger u 3 Leoparden. In dem andern das schönste Tier, was ich je gesehen habe, ein afrikanischer Löw mit schwarzer ungeheurer Mähne, eine höchst seltene Art, dann ein wundervoller Tiger und ein Panther. Van Amburgh tritt nun in den Käfig, die Tiere springen an ihn herauf, er legt seinen Kopf in den Rachen der Löwen etc. – kurz er macht das Tollkühnste, was einer nur tun kann, so dass man geneigt ist, an die Geschichte des Daniels in den babylonischen Löwengruben zu glauben. – Das schönste ist aber unstreitig, wenn er den grossen Löwen reizt. Dieses gewaltige Tier hebt sich senkrecht am Gitter in die Höhe, u öffnet mit fürchterlichem Gebrüll seinen ungeheuern Rachen, indem er mit der einen Tatze nach ihm haut, – da hebt van Amburgh bloss die Hand auf u der Löwe kriecht in den Winkel – er legt sich dann zwischen Tiger u. Löwe hin u spielt mit ihnen. Dann bringt er ein Schaf – Tiger u Panther machen sich sprungfertig – van Amburgh hält unverwandt sein Auge auf sie. Der Löwe lässt sich vom Schafe belecken u blickt kaum auf. Der Tiger brüllt u sein Auge glänzt fürchterlich u doch wagt er nicht zu zanken. Übrigens glaub’ ich doch, dass bei einem solchen Manöver der Tollkühne sein Leben einbüssen wird. Die Gruppen u Stellungen dieser herrlichen Tiere zusammen sind oft enzückend, namentlich wenn die prachtvollen Leoparden wie Schildhalter am Gitter sich erheben u einander angrinsen. Denke man sich dieses Bild in ein patentes Drama eingewebt, schöne Dekorationen dazu u überhaupt das Gitter anders arrangiert, dabei eine schöne Musik, (denn die muss immer dabei [sein]) – bei der unheimlichen Stille, die im ganzen Theater herrscht, so müsste das entzückend sein.«(10)

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (1802-1873), Isaac van Amburgh and his Animals (1839; Royal Collection, Windsor)

This passage, in all its impulsive liveliness, does reveal much of Giovani Morelli’s personality, and not only of Giovanni Morelli as a young man. If we would not be aware that this passage was by Morelli, it would not cause a difficult problem of attribution either, since a combination of distinctive features does show here:

ALEXANDER PUSHKIN, EX UNGUE LEONEM (1825):

The other day it was that I penned down some verses

That unsigned I chose to edit in the following.

The shabby critic which did penetrate them pettifoggingly

And left, like I did, then unsigned his scrawl –

To him his follies were of little use,

Not more than ’twas my secrecy to me.

For to recognize my lion’s claw was simple here

And I, on my part, could appreciate a donkey’s ear.

(very free translation/paraphrase: DS; after Puschkin [1985], p. 210;

see also Cabinet II)

a) the author being impulsive as to the expression of his enthusiasm for physical sensation, here: the attraction of wild animals’ beauty, of physical strength, and of seemingly civilized wild nature, controlled by a single, extraordinary man, being seemingly foolhearted.

b) the author being impulsive as to the expression of his very dismissive critique of the staging of the show, immediately turning into an ambitious competitive thinking how this could be done better.

c) the author showing his very flexible mind, being able not only to think of the arrangement differently, but referring also to the literary, here Biblical tradition to interpret what he does see, if sceptically.

d) the author suddenly turning into a sceptic (or allowing the sceptic in him to raise his voice) as to the risk the wild animal tamer is obviously taking (here the scepticism is directed to what happens on stage; while it is also characteristic for Morelli, that these sudden sceptic turns are directed against his own writing and himself).

e) the author, finally, showing not only curiosity and a searching passionate enthusiasm, but also – and here rather implicitly – the need to be confirmed and guided by a mentor responding to his ideas, since his own ideas do show rather fragmentarily, impulsive and hence yet unformed.

What Giovanni Morelli does in this very passage, as generally in his letters to Genelli, is to show himself as a talented and promising writer (and thus, as also Genelli thought, he did show as a poet-to-be). Which is, the description of a wild animals show is also to be regarded as an exercise in writing. And if Morelli is describing visual sensations, it is not mainly for the sake of conveying a joy of looking, although, certainly, he did enjoy the experience of watching, but for the sake of a description resulting from that experience (which, in some sense, is revealing also in terms of a description of himself as the young man he was at that time). Looking and observing, at this time of his life – for a Sturm und Drang Morelli, as one might say –, is meant to gather materials, to find a perspective on things, and to develop as a writer. His looking, already influenced by having much read, finds its expression in writing, and his writing, one might say, again stimulates his again looking. To see more, to better express himself, to interpret more acutely what he does see. And young Giovanni Morelli also expressively turned to literature, if in need for models of acute observation of all things human, for example to Shakespeare and to Alessandro Manzoni.(11) His looking and writing, also being appreciative, that is showing the inclination to enjoy the sensations of life, seeks also for a deeper insight into human things, finding such an insight primarily in literature, as in his friend and mentor Genelli, whom, as we have seen above, Morelli did also see as someone having things, having life taped. Thus with the above quoted description we find Morelli drawing on resources, showing him how one might look at things, and we find him practicing, at one occasion, the looking at things, testifying his experience by giving an account to Genelli.

If the above quoted passage does show Morelli as an impulsive, passionately searching and also ambitious young man, it might not yet be obvious that his impulsiveness, not inclined to develop literary structure, literary drama patiently, might also have been one reason, and maybe the one reason why Morelli, in the end, did not become a writer. The elaborating of his ideas showed not to be his strength throughout his life, and he certainly was lacking patience and discipline, not only as to the elaborating of literary ideas, that, in just one impulse, he tended to sketch out fragmentarily, and certainly his scepticism worked as his inner critic, that, in the end, did not allow him to be convinced that he actually was a writer (beyond the wanting to be one, that is: the wanting to fit into such a role).

Which is certainly a pity, since much of Giovanni Morelli’s experiences in life and in looking at life did not find an expression in words, and has not been transmitted, since he dropped his ambition. Which is that, at least in some sense, these experiences are mostly lost. And his rich experiences only to a very little degree found their expression in connoisseurial writings during the second half of his lifetime.

But on the other hand, it is residing with biographers of Morelli, to recover these experiences. Which, to some degree is possible, because sources such as is the correspondence with Genelli, reveal much of Sturm und Drang Morelli and his visual apprenticeship, in his trying to develop a grasp of life that was also to become the backdrop of his looking at art. And here, at this very moment, we perhaps find the signature of Morelli’s whole life, with a tremendously vital look at life on the one hand, and a tremendously rich experience in various fields of life, while on the other hand the Morelli of art historical tradition is seen as one of the most single-minded art historians ever, because Morelli has become the embodiment of an extremly specialized and focussed looking at problems of attribution only, resulting with this later image of Morelli having replaced any other image, like that of Sturm und Drang Morelli, anxious to gather experiences in looking, and anxious as well as ambitious to express himself in writing. In sum: It resides with a visual biography of Giovanni Morelli, and it is the challenge of such an undertaking, to bring this other image, as many other images back, resulting also with a more vital image of Morelli, connoisseur of art, his looking at art, and with a paradigm of how one could address the issue of a most vital visual person’s most vital visual biography as such, addressing also the question, which might be one of the key questions of the biography of Morelli: how did he get from point a, the Sturm und Drang Morelli being anxious to gather visual experiences and to find insight into human and natural things, to point b, the connoisseur of art focussing on extremly sought-out and specialized problems of attribution? We perhaps will find the answer, if following farther our path, the path of a thinking pair of eyes’ biography, in a word, the path of visual biography.

*

RIVALRY AND FRIENDSHIP: MORELLI AND THE LITERARY WORLD OF THE FRIZZONI BROTHERS

It does not seem to be advisable to speak, if one is being a poet and in need of patron’s support, of the home country of one’s patrons disparagingly.

But exactly this August von Platen-Hallermünde, Graf Platen, had done: he had spoken disparagingly of Lombardy, the home country of the Frizzoni brothers, that, although being of Swiss origins, were no less Lombardic patriots than Giovanni Morelli was (who, as we have shown, and no less than his friends, was actually of Swiss origins).(12)

Graf Platen, in fact, as the Frizzoni brothers even had reported to no other than Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1830, had not particularly liked Lombardic cities (Venetia he had liked better, apparently, particularly Verona, but not Milan). And Goethe had mused that this perhaps might have been only due to the weather (see below).

One does not know what Giovanni Morelli thought, of Platen’s poem that was culminating in the poet hoping that ›never, o never‹ he would have to return to that brumous country, a country so dear to Morelli. But since Morelli probably considered the friendship of his friends with Graf Platen as a matter of his somewhat elder friends, he may have remained silent as to the matter.

The Frizzoni brothers, as patrons as well as friends, did not allow their friendship with Graf Platen to be troubled by this matter (although they seemed to have demanded a retrieval of Lombardy’s honor), and Morelli certainly, to some degree looked up to his friends, who had not only been mentored by a private teacher, a Saxonian named Gustav Gündel, and had acquired, as he was going to, a sterling education, but had also begun to entertain friendships with men of letters.

With Platen on the one hand, but also with Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, a particularly renowned German connoisseur of art, who did also write on Lombardy, but seems to have remained more cautious than Graf Platen.(13)

And if one thing is for certain, then it is that Morelli did not only look up to his friends, but also did particularly observe to whom exactly his friends owed their literary education, and also their education as to all things relating to the visual arts. In other words: Giovanni Morelli certainly had an eye on all men of letters that his friends were associating with (later also on Jacob Burckhardt), since his stance as far as the education of the Frizzoni brothers was concerned was an affectionate rivalry. That led, among other things, certainly to a careful studying of several writings by Rumohr from early on, even if it might have led less to a careful studying of the poems by Graf Platen.

(Picture: Sailko;

compare GM to Federico Frizzoni, 21 February 1838

(Frizzoni 1893, p. XXXIff.)

(Picture: staedelmuseum.de;

compare again GM to Federico Frizzoni,

21 February 1838

(Frizzoni 1893, p. XXXIff.)

One does not know exactly what had made Morelli caused to wrangle with Federico Frizzoni, but roughly, it seems clear that the latter had responded rather critically to one particularly exuberant and enthusiastic letter by friend Morell, a letter enthusiastically praising Homer and Shakespeare, while disparaging, in tendency, German epics.(14) Perhaps it had only been the pointing to the obvious (or a little chaffing as to the matter), that Morelli felt obviously attracted by sensual vitality and seemed to appreciate art if only characters were being made of flesh and blood, while he seemed not to appreciate, or less, the qualitities inherent to German epics, the emotions particularly and maybe also the intellectual content.

Which had resulted with Morelli, still affectionately, but more and more passionately and also more and more furiously to defend himself (also drawing on thoughts and expressions he had adapted from Genelli),(15) and in defending himself as well as his innate sensualism, to show two things that may particularly concern us here:

because on the one hand he did indeed declare to be attracted to sensual vitality, to ›flesh and blood‹, in literature as well as in the visual arts, but on the other hand he did also show that he did know to respond to the criticism (and/or to the chaffing), and that he, indirectly, in defending himself, indeed acknowledged other ways, the Frizzoni way, as it were, to look at art. And why he was doing that, very significantly, also the name of Rumohr was dropped (indirectly, thus, Morelli was, and already as early as that, also wrangling with Rumohr, as he was in his later years, showing that he respected Rumohr, and indirectly his friends, but still trying to find a way, if possible, to show that he was in the right).(16)

This wrangling, in sum, is most significant, as to a showing to us, how these close friends were interacting, friends, whose ways to look at art were seemingly different, but also complimentary views.

In sum: Giovanni Morelli, although indeed responding very directly to sensual values – and one may understand ›flesh‹, particularly flesh, young flesh, very literally here – could also, especially if being stimulated to do so, appreciate the more intellectual, the more inherent values in works of art, because, in his passionate responding, he was ostentatiously doing so, saying that, naturally he could do so, and also showing that he could do so (albeit that someone was needed to stimulate him to do so, that is to reveal himself, in all sides of his nature, more clearly).

It might not have been characteristic for him to put his sensualism in second place, but since his friendship with Federico Frizzoni and Giovanni Frizzoni was close, he was, as it were, constantly confronted with more intellectually oriented views that he had to acknowledge, although his preferences of how to look at art were, at the moment, different, and while the sheer joy of looking, apparently to some degree did outshadow his also showing capability to interpret. Because this capability did also reveal, if opportunity was given, and particularly if Morelli went on, driven by his passionate enthusiasm, to describe works of art as for example the portrait of Don Quixote by Genelli (see chapter Visual Apprenticehsip II).

The literary world of the Frizzoni brothers, thus, meant a challenge to Morelli who did devour as much literature and poetry as he could (and he did also show that he indeed did so), but his preferences were slightly different, in that he did, being somewhat younger than the Frizzoni brothers, already look back at the Goethezeit, and at the age of the German Romantik, and in that, similar to the German writers of the Pre-March era, brought also a distinct irony (and less respect) into that looking back.

A looking back that was an expression of a wanting to find an own way into the future, but still showed, in not at all dismissing mainstream traditions, that it remained in close connection with these traditions.

That were not being considered as alternatives, resulting in particular identities, but as very diverse offsprings of own creations. And if we see Giovanni Morelli, no less than swirling across the literary landscape of his day, meeting with one writer after another (see our survey below); and the backdrop of his friendship with the Frizzoni brothers does remind us that he stayed in touch with friends that had incorporated and thus were living slightly different values, and that it was just this not quite agreeing that worked as an intellectual stimulus to Giovanni Morelli. Causing him, at times, to wrangle, but also causing him, driven by his own intellectual curiosity and his inclination to socialize, to swirl, to search and to explore.

The beginnings of Giovanni Morelli’s own literary ambition date of c. 1836 and hence not of the age of the Weimarer Klassik nor of the German Frühromantik, but of the Vormärz (›Pre-March-Era‹) and in some sense of the German Spätromantik. The Vormärz yet looked back at Classicism and Romantic school, and Morelli (in cooperation with Veit Engelhardt) spoke, in 1845, of the ›boundaries between classicism and romanticism that today could only be of importance for pedants and fools‹ (Engelhardt/Morelli 1845a, p. 2026: »jene Schranken zwischen Klassizismus und Romantizismus, die heutzutage nur noch für Pedanten und Schwachköpfe von Wichtigkeit sein können«).

The beginnings of Giovanni Morelli’s own literary ambition date of c. 1836 and hence not of the age of the Weimarer Klassik nor of the German Frühromantik, but of the Vormärz (›Pre-March-Era‹) and in some sense of the German Spätromantik. The Vormärz yet looked back at Classicism and Romantic school, and Morelli (in cooperation with Veit Engelhardt) spoke, in 1845, of the ›boundaries between classicism and romanticism that today could only be of importance for pedants and fools‹ (Engelhardt/Morelli 1845a, p. 2026: »jene Schranken zwischen Klassizismus und Romantizismus, die heutzutage nur noch für Pedanten und Schwachköpfe von Wichtigkeit sein können«).

Since it is thus possible, especially if we take into consideration the long neglected correspondence with Genelli, to study Morelli’s sympathies and antipathies, his interests and his passions as to reading more in depth, it is possible to situate Morelli very precisely within the literary landscape of his day. Which is also: that his relation to the literary heritage of the Weimarer Klassik and that to the heritage of the Romantik can be studied more in detail. But it does not make sense any longer – and actually it did never make much sense – to explain his later development to being a connoisseur exclusively with his being in touch with literary circles of the Spätromantik, or to see his own writings exclusively being inspired by the Frühromantik. Nor does one see – at any time of his life (as Edgar Wind once had it; see Wind 1985, p. 42, with the influential Reith lecture on Morelli of 1960) – a »cult of the fragment«.

In fact: Neither is there such a cult at any time of his life, nor does the intellectual biography of Giovanni Morelli owe anything to a frühromantische theory of the fragment, and – most important –: the intellectual biography of Giovanni Morelli shows him, until being 40-years-old, not much interested in becoming a connoisseur of art at all. That is: Explaining his development to being a connoisseur of art exclusively by his early being in touch with the Romantik, is in a double sense questionable, if not to say wrong: because, for one, there is no such being influenced by a theory of the fragment, nor, secondly, is there any interest to link a theory of connoisseurial practices with theories of the Romantik (except, and this is the significant, if rather hidden exception, with ideas of philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling).

In sum: being obsessed with a putative link between Giovanni Morelli and the Frühromantik runs in danger to block the view onto the actual intellectual biography of Giovanni Morelli which has much to do with literature (and Socratic or romantic irony is always being a part of it), and also with writers that we count among the writers of the age of the Romantik, but in a rather different sense than once Edgar Wind, simplifying the biography of Morelli in the extreme, did assume. And in the following we attempt to give a survey as to the relations of Giovanni Morelli to several writers, being active in the German Pre-March era, later followed by a survey on how Morelli saw the two Italian writers of the day that were of the utmost importance to him: Giovanni Battista Niccolini and Alessandro Manzoni.

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND THE GERMAN LITERARY SCENE OF THE PRE-MARCH ERA

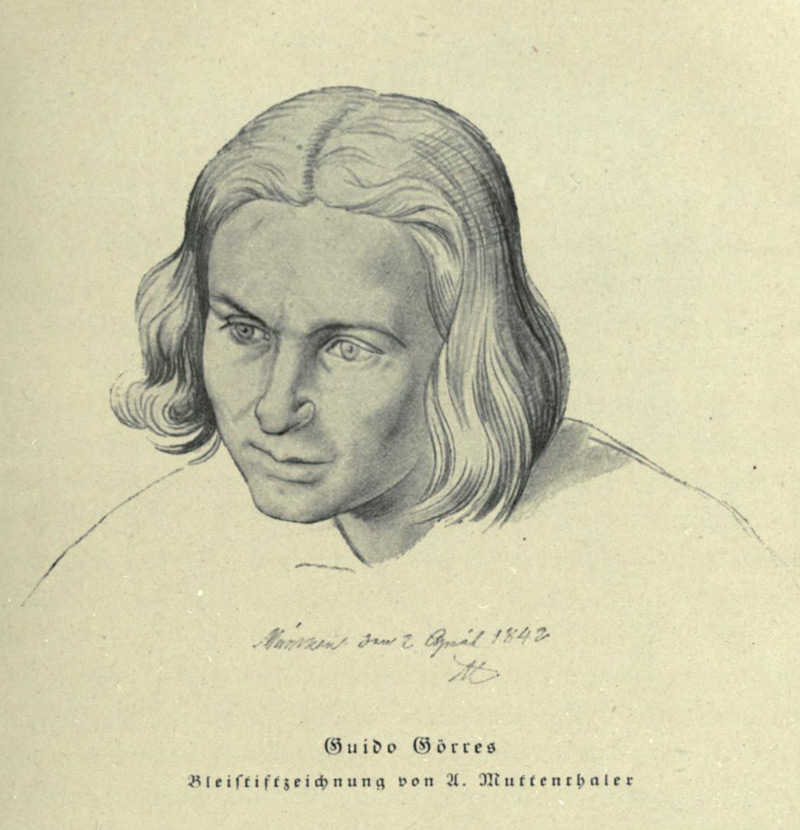

Clemens Brentano in 1837, painted by Emilie Linder, and Guido Görres

Heinrich Heine in 1831 (on the left), and August Graf Platen

Friedrich Rückert (in 1818)

Again Rückert (before 1841)

Ludwig Tieck in 1838, the year in which Giovanni Morelli met him

Poet Ludwig Tieck sitting to the portrait by sculptor David d’Angers, and painted by Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein

Bettina von Arnim (1785-1859)

(Picture: Profile of Bettina von Arnim/youtube.com)

Munich I: The Cultural Climate.

The inspiration for his first literary work, the Balvi magnus (Morelli 1836), Morelli had taken from Das Narrenhaus von Wilhelm von Kaulbach (Kaulbach 1836; see also Waldvogel 2007; and for the link see Anderson 1991b, p. 33, with the letter by GM to Federico Frizzoni, 14 October 1836), a work containing comments upon the Kaulbach drawing of a madhouse, comments by Guido Görres, the son of publicist and historian Joseph Görres, who was, like Morelli, associating with poet Clemens Brentano.

Munich II: Conversing with Clemens Brentano.

»Mit [Clemens] Brentano komme ich weniger oft als früher zusammen, ebenso mit [Joseph] Görres, dessen neuestes Werk, Die Mystik, eine ganz merkwürdige Erscheinung ist.«

(GM to Federico Frizzoni, 14 July 1837 (Frizzoni 1893, p. XVIIIf.)

Translations

»Dass der himmlische Hanswurst [Clemens Brentano] diese Welt [hat] verlassen müssen [Brentano died in 1842], dies werden Sie wohl erfahren haben – ob es ihm dort gestattet sein wird, diese Rolle fortzusetzen, zu welcher er hier so manche Proben machte, ist halt die Frage, wenn er auch noch so sehr beteuerte, dass es im Himmel nichts weniger denn langweilig u steif zugehe.«

(Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 23 September 1842)

Erlangen I: Portraying Erlangen à la Heinrich Heine.

Given that Giovanni Morelli knew of the friendship of his friends, the Frizzoni brothers from Bergamo, with poet Graf Platen, who had quarreled with poet Heinrich Heine, a feud that it being remembered as the Platen-Affäre, as a part of which Heine attacked Platen in his Reisebilder, given all that – it was a subtly frivolous hint à la Morelli to his friends, if he did portrait the city of Erlangen à la Heine, that is in the style of the very Reisebilder (for Morelli, in 1851, referring to Goethe, Schiller, Uhland, Hölty, Heine and Rückert see also Frizzoni 1893, p. XLVI).

»Nicht nur als Universitätsstadt ist Erlangen berühmt, sondern auch durch seine Handschuhe, Pfeifenspitzen und Strumpffabriken, und in neuester Zeit durch seine vortreffliche Gedichtfabrik ist es in ganz Deutschland sehr hoch geschätzt – was aber Erlangen für Bayern, Preussen und Sachsen in besonderer Wichtigkeit erhält, ist die protestantische, fanatische Sekte der Mystiker. […]«

(GM to Federico Frizzoni, 15 October 1837 (Frizzoni 1893, p. XV))

Erlangen II: Portraying Friedrich Rückert.

»Rückert ist 49 Jahre alt. Sein Äusseres ist höchst bedeutend; für manchen vielleicht zurückschreckend, für solche aber, die besser lesen können, anziehend. Er ist sehr gross (in jeder Beziehung der grösste Erlanger; um einen Kopf höher als ich). Dabei aber proportioniert; denn seinem Rücken nach sollte man ihn für keinen Gelehrten ansehen. Sein stets ernstes Gesicht, das durch die Pocken etwas gelitten, gehört unter die imposantesten, die ich gesehen. Er hat eine ziemlich niedere, leichtgewölbte, vorstehende Stirn, tiefliegende, schwarze, funkelnde Augen, deren Feuer, besonders wenn er lächelt, recht glüht, einen etwas zusammengekniffenen, breiten Mund – eine kleine, formlose Nase (der einzige unbedeutende Teil in seinem Gesicht) und stark vorstehende Backenknochen. Das Gesicht ist nicht fett, sondern mehr eingefallen. Das etwas lange, grauliche Haar ist gescheitelt und hinter die Ohren gestrichen. Seine Bewegungen sind schnell und kräftig, was ich besonders neulich, als er mich besuchte und das Gespräch auf die indischen Gaukler kam, zu sehen Gelegenheit hatte, wo er sich im Eifer der Erzählung von ihren fast unglaublichen Kunststücken plötzlich vom Stuhle erhob und durch Aktionen und Gestikulationen aller Art seine Beschreibung lebendiger und anschaulicher zu machen strebte. Der Dichter der Geharnischten Sonette ist in ihm nicht zu verkennen. Sein liebstes Gespräch ist über die verschiedenen Sprachen, ihren Geist und ihre Formen, und nie verlasse ich ihn ohne einen grossen Nutzen. Um recht viel von ihm zu geniessen, habe ich mich nun an die Grimm’sche deutsche Grammatik gemacht und an die alten und mittelalterlichen Dichter, die ich schon seit lange etwas vernachlässigt hatte, weil es mir bei ihnen wie bei der altdeutschen, gepriesenen bildenden Kunst ging – ich erbaute mich an ihren nebelhaften und krüppelhaften, verhungerten Gestalten, denen alles Sinnliche abgeht, sehr wenig, und selbst die Nibelungen, so hohen Genuss sie mir verschafft haben, werden mir zuwider, sobald ich sie an den Homer halte. […]

Rückert gehört hier unter die wenigen Gelehrten, die ganz unabhängig und frei von den mystischen Faktionen […] geblieben sind; er lebt für sich eingezogen und still und hat bloss einen Freund (Professor Kopp, ein Mann von immenser Gelehrsamkeit), mit dem er umgeht. Von morgens 4 bis abends 10 Uhr arbeitet er fast ununterbrochen fort, und so erscheint seine Produktivität weniger wunderbar, wie auch seine enorme Sprachenkenntniss (Griechisch, Latein, Italienisch, Spanisch, Französisch, Englisch, Norwegisch, Dänisch, Arabisch, Hebräisch, Persisch, Sanskrit, und was weiss ich noch alles). Besuch machen ist nicht seine Sache; um so höher schätze ich seine Besuche, mit denen er mich schon einigemal beehrt hat. – Jede Woche bringe ich einige Stunden bei ihm zu und werde, seit ich gesehen, dass er mich wohl leiden mag, einige mehr dazu addieren. Neulich las er mir mehrere Gedichte eines gewissen Kotzenberg aus Bremen, die dieser ihm zur Beurtheilung überschickt hatte, vor. […]«

(GM to Federico Frizzoni, 15 October 1837 (one of the most hilarious letters ever written: see Frizzoni 1893, pp. XIXff., quoted above from p. XXIIf.; orthography slightly modernized; in 1836/37 (and until 1839) Friedrich Rückert was publishing his several volumes oeuvre Die Weisheit des Brahmanen)

Dresden: Hearing Ludwig Tieck Reading Aloud.

»Wenn ich nun die Individualität Alfieris gegen die Tiecks z.b. halte, wie erbärmlich erscheint mir nicht letzterer – als Mensch hat er nicht eine Spur einer dichterischen Seele, auf mich wenigstens hat seine höfische, berechnete, superfeine, – kurz seine falsche Art u Weise den unangenehmsten Eindruck gemacht u ich würde ihn nie wieder besuchen, wenn er fürs erste sich mir nicht so überaus gefällig u artig erwiesen hätte, u wenn ich zweitens nicht über spanische Literatur vieles von ihm lernen könnte. Auch kann ich seine Vorlesungen, zumal Shakespeare’scher Stücke, nicht genug bewundern; das nähere Verständnis Lears verdank’ ich z.b. ganz u gar seiner Vorlesung. Dass er alles u nicht nur den Shakespeare, wie es gewöhnlich heisst, gut vorliest, davon haben mich d. Alceste des Euripides, die ich vorgeschlagen hatte, u dann einige Lustspiele Heinrich v. Kleists überzeugt. Auch den Goldoni las er meisterhaft vor, u ein ungemein feines Gefühl lässt sich ihm keineswegs absprechen. Seine Natur ist so weiblich, dass sie sich an alles schmiegen u alles aufnehmen kann – ich meine, seine poetische Natur; – denn selbst hat er nichts weibliches in seinem Charakter, wenn man d. alten Weiber vielleicht ausnimmt […].«

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 14 June 1838; for Morelli referring, in 1864, to having read in his youth poems by Bürger, Hölderlin, Tieck and other poets of the Romantic school see Panzeri/Bravi (eds.) 1987, p. 128)

Berlin: Charming Bettina von Arnim (and being charmed by her).

»›Ei, das ist schön, Herr Morell, dass Sie auch Sinn für Malerei haben‹, sagte mir Bettina [von Arnim].

›Sie sind auch ein Kunstkenner?‹, fragte etwas vorwitzig der Herr Baron [Mayer Carl von Rothschild]. – Da ich ihm aber gar keine Antwort gab, so warf der junge Held einen lächelnden Blick auf die Damen und drehte dabei seinen Brillantring am kleinen Finger.«

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 12 November 1838)

Translations

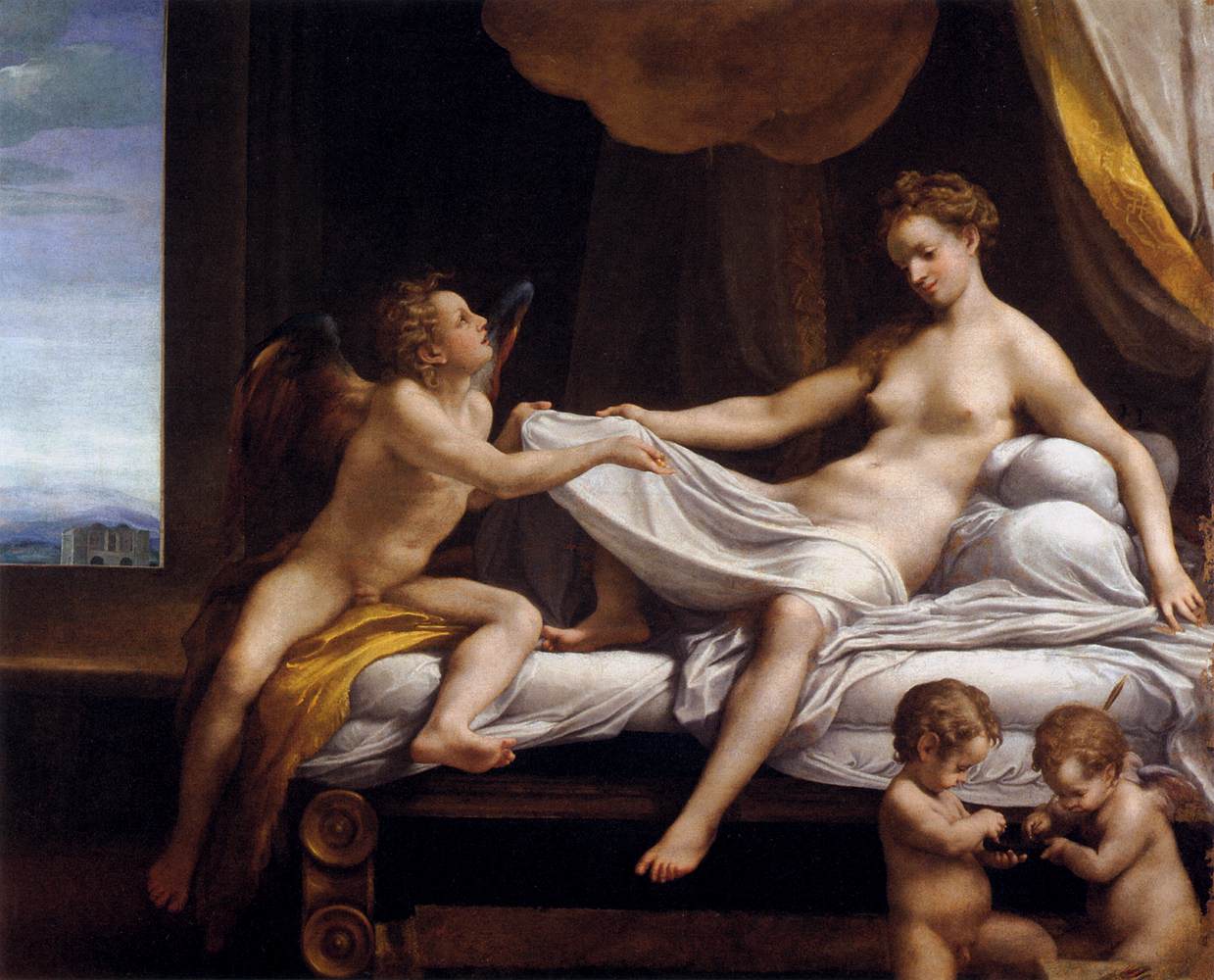

›Upon this she [Bettina von Arnim] grabbed a worn out armchair, trundled it to a quite large sofa, above which a copy of the Io by Correggio was hanging, lied down on the sofa with legs full length (à la Schelmuffski), namely alongside, whilst she asked me to be seated next to her.‹

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 14, 23, 24 June 1838)

›I followed her [Bettina von Arnim] into the adjoining studio, where the Io is hanging. Beneath the door she yet said jokingly to [Mayer Carl von] Rothschild, that he should behave well. Then she locked the two of us in, throwed herself onto the sofa and with one hand tapped on the free space next to her – ›there, my friend, be seated‹.‹

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 12 November 1838)

»Sie [Bettina von Arnim] ergriff darauf einen versessenen Lehnsessel und rollte ihn zu einem ziemlich grossen Canapé, über welchem eine Copie der Io von Correggio hing, legte sich sodann ›mit gleichen Beinen‹ (à la Schelmuffski) aufs Sofa und zwar den langen Weg, indem sie mich an ihrer Seite Platz zu nehmen bat.«

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 14, 23, 24 June 1838)

»Ich folgte ihr [Bettina von Arnim] in das anstossende Atelier, wo die Io hängt. Uner der Tür sagte sie noch scherzend dem [Mayer Carl von] Rothschild, er solle sich gut aufführen. Dann schloss sie uns beide ein, warf sich auf das Canapé und klopfte mit einer Hand auf den freien Platz neben ihr – ›da, mein Freund, nehmen Sie Platz‹.«

(GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 12 November 1838)

Mayer Carl von Rothschild (picture: ub.uni-frankfurt.de)

*

THE SENSUAL SIDE OF LOOKING, THE SENSUAL SIDE OF ART

In 1878 62-year-old Morelli was to take note of his 31-year-old apprentice-to-be Jean Paul Richter praising enthusiastically the Antiope by Correggio (now rather called Venus, Satyr, and Cupid) in the Louvre. And wholeheartedly, as Morelli wrote to Richter, he wanted to join in praising that painting.(17)

What Morelli did not say, then, was that, many years earlier, in 1840, he had, upon Genelli’s request, made this particular painting the subject of an enthusiastic description, had praised Antiope as appearing to him even more beautiful than Io or Leda.(18) In fact 24-year-old Morelli had, in describing the Louvre picture out of memory in 1840,(19) elaborated his description in terms of a scene, evolving in time. But his text – unfortunately only fragmentarily being extant – only reaches the point of the story when the satyr arrives. Which is: we have a description of Venus (or Antiope) by Morelli, but we do not have his full description of what happened, in his view, with the satyr arriving (or even afterwards).

Correggio, as is the case certainly for many other viewers and writers, is without any doubt to be regarded as the one painter that confronted Morelli with sensuality, female sensuality. And since we also can trace how his views on Correggio, over the years, did evolve, we can also say that Correggio was the one painter who made Morelli also think about sensuality. Female sensuality. And sensuality in art as such. This subject, certainly a delicate one, inserts into an even more broad (and also delicate) chapter on ›Morelli and women, Morelli’s views of women, and women’s view of Morelli‹. A chapter, certainly comprising also many a secret compartment that we are neither able nor inclined to open, and a chapter we are also not going to elaborate as a chapter of its own, but should like to address, in that we try to characterize Morelli’s views of women in art, women in life, and on female sensuality in art and life. Naturally this is only possible in characterizing also his views of men, of masculinity,(20) and from the very start we should also take note that there was not one image of women or men that Morelli cherished, but many. And very diverse were also, maybe not the women Morelli was attracted to, but the women Morelli encountered during his studenthood and beyond, and did also describe.

One might mention here again (or not), that Morelli never got married. That throughout of his life he lived, sometimes referring to the fact more waggishly, and sometimes more wistfully, as a bachelor.(21) But this only bears on the very basic facts (and more interesting are here, as generally, the nuances), and we might also add, and also as a basic fact, that Morelli, as a man many women felt being attracted to, could not stand it to be monopolized by women. Although he enjoyed the company of very lively, intelligent and in every respect very attractive women, and usually also for quite some time.(22)

Nonetheless, if Morelli never got married, one might also relate this fact to the fact, that he also, and maybe more than anything, loved his freedom. That in some respect it was his freedom he was married to. Which resulted, among other things and in combining with other, and also economical factors, with the fact of Morelli never getting married. And since he kept a good and very solid relation to his mother, it was her being present in her son’s life, if only in the backdrop of her son’s life, more than any other woman.(23) Since no other woman, although Morelli several times did fall in love with a woman,(24) is to be found as the one woman in his life. And this, probably, also to Morelli’s chagrin, relativized though by his love of freedom and the satisfaction he got from many friendships and his studying of literature and of the visual arts.

If also from many affairs with women (and, possibly, also with men) is simply not known, due to Morelli’s general secretiveness, but we tend to think that this was rather not the case.

Giulia Grisi (1811-1869)

(Source: Grandville [1979], p. 38; originally published in 1844)

It is less easy to imagine Morelli going to the opera than imagining him going to the theatre or to the circus, but in fact he did go to the opera, and also enthusiastically, at least in Paris;(25) and it is striking that music as such did play a rather minor role in later years. Not during his studenthood though, when he actually did enjoy music on various occasions,(26) but music as an art form got indeed outshadowed by the time, first by his passion for literature and second, and more and more, by his passion for the visual arts and its study.

It was at the opera, nonetheless, that he fell in love, which means here, that he admittedly, and probably only for a short time, had a crush on opera singer Giulia Grisi,(27) whom he probably never did meet in person, since, while he felt being attracted to various women representing stage professions, as to Giulia Grisi, and later to an Italian singer, and as also in Paris to an Italian female circus rider, he felt that this was not exactly the milieu he should be attracted to.(28) Judged by his own moral or social standards.

But obviously he was (and also later), and Giulia Grisi as well as the Italian circus rider do represent probably women Morelli admired from a distance, representing the audience, having fallen in love with a stage personality, an artist, a star.

It is not far fetched at all to assume that Grandville might have found his inspiration,

like Morelli, in the ›Cirque Franconi‹, that is the Cirque d’été

(source of picture: Grandville [1979], p. 38; detail)

(Picture: pg.pagesperso-orange.fr)

›If this divine creature, dressed like a nymph, with her coal-black long hair, her sparkling eyes, the gracious movements of her slim and ample body, on her Andalusian gray, in bright candlelight and to the most cheerful music in soughing gallop does ride by oneself, waving the garland of roses – one’s heart dances with joy in one’s body, for the human (being) being that beautiful a creature.‹

··························································

»Wenn dieses göttliche Geschöpf, wie eine Nymphe gekleidet, mit ihrem kohlschwarzem langen Haar, ihren funkelnden Augen, den graziösen Bewegungen ihres schlanken & üppigen Leibes, auf ihrem andalusischen Schimmel beim hellen Kerzenschein u der heitersten Musik in rauschendem Galopp an einem vorbei reitet & die Girlande von Rosen schwenkt – da tanzt einem das Herz im Leibe vor Freude, dass der Mensch ein so schönes Geschöpf ist.«(29)

The features of character that Morelli considered as being male features he was to enlist, many years later, in regard to Michelangelo Buonarroti, and features that he considered as being female in regard to other artists (with again Correggio among them).(30) But if he, then, wanted also to express what he considered to be male and female nature in its essence – he knew also that real life was much more complicated. Since for example he considered Lady Eastlake, the wife of painter-connoisseur Charles Lock Eastlake, as a mannish woman (»Mannweib«),(31) and this obviously due to her resolute nature and her being quickly decided and taking, then, usually a very firm stance.(32)

Which was exactly the opposite of Morelli’s scepticism, his oscillating judgment, that showed, if not to everyone, particularly in connoisseurship.(33) And Lady Eastlake, as also writer Malwida von Meysenbug, and also philantropist and collector (and also novelist) Henriette Hertz, tended to overlook this very sceptical and often uncertain side of Morelli’s nature, that, nonetheless and occasionally was inclined to a wanting to impress people and also women by taking a very firm stance in certain connoisseurial matters, and particularly with these woman, he was also successful in wanting to impress them.(34)

And thus, he seems also and particularly to have impressed Lady Eastlake, who, in her portrait of Morelli, did idealize him to no little degree, in enlisting, rather uncritically his alleged triumphs (that in the mean time have all been challenged again).(35)

Morelli’s views on men and women were seen as being rather conservative, and this from the perspective of a rather progressive woman like Louise M. Richter, who did know him from close (and who had translated one book of his into English), and who found that his judgment on Lady Eastlake showed that Morelli was, all in all, a man of the ›good old time‹.(36)

Lady Eastlake, on her part, seems also to be affirming this, due to her remark that writer Bettina von Arnim, with whom Morelli had intensely associated with in 1838, had not been the kind of woman Morelli was actually drawn to.(37) But as always with Morelli: various aspects add to a rather heterogeneous and often ambiguous picture: since the associating with remarkable personalities like Lady Eastlake, Bettina von Arnim, the Prussian Crown Princess Victoria (and daughter of Queen Victoria) and last but not least: with salonnière Donna Laura Minghetti was to be a constant in Morelli’s life, although he was, also a constant, occasionally in fear of being monopolized, particularly by women like Donna Laura or Bettina von Arnim (whom he in fact, contrary to Lady Eastlake’s asserting, had also liked).(38)

The other and corresponding constant might have been that he was rather drawn to gentle and rather passive women who also did admire him, or that he could admire these women, without being all too engaging. And several woman like a Miss Holzschuher of Nurimberg,(39) or other women, often not even named,(40) appear in the most diverse biographical scenarios, without ever playing more than a minor, and often – be it allowed to say – more decorative role. A cliché-role certainly, and corresponding to the role of the hotheaded man, having to defend somebody’s honor in duelling himself,(41) a role that Morelli did imagine himself in, while, arguably, he never did duel himself, nor did he ever marry. He could be hotheadded (as he could be sensitive, and even playfully and waggishly cuddly),(42) as much as he could be undecided, probably and generally fearing to commit, and to be all too explicit.

And if, for example, he did actually fight in the battle of Novara in 1849, remains unknown to the historian, nonetheless, we do also know that it was again Lady Eastlake, who must have asked about Morelli’s role in that very battle – since she was the only one to mention, that Morelli apparently had, on the eve of the battle, arrived on the scene.(43)

(Source: Gould 1976,

monochrome plate 97C after p. 307)

The challenge that now a painter like Correggio did present the Victorian Age with, can be described in addressing Morelli’s taking a stance in regard to Correggio’s sensuality. And as we have seen, he was, in his studenhood, most enthusiastic about the Louvre’s Venus (and waggishly he had referred to the copy of the Io, hanging over the sofa in the drawing-room of Bettina von Arnim; see picture within the presentation above).

But with Correggio, in later years he was also to associate a sensuality that was on the brink of being corrupted (as regards particularly the Danae), revealing also a potential to corrupt a beholder, that is: to corrupt others in exerting corrupting an influence.(44)

And if the Danae was, in his view, on the brink as to exerting such an influence, the topic did also play a role in his rejecting of the Dresden Reading Magdalen as being by Correggio. Since he perceived this particular work as a painting instrumentalizing sensuality for other, namely Jesuit purposes (a motif that was, later to echo, in Berenson).(45)

Sensuality could also be misused, in other words, and between the Danae and the Reading Magdalen Morelli was to draw his line – resulting also with the excluding of the Magdalen from the painter’s oeuvre as he saw it,(46) and revealing how moral standards, how various ways of sensuality could play a role in connoisseurship, revealing at the same time, maybe not Morelli’s moral standards as such, but at least his declared moral standards, and his – more or less declared – being receptive as to female sensuality (rendered by male painters) as a man.

For Morelli’s view of ›magnetism‹ in Correggio

see Cabinet II of the Giovanni Morelli Study

*

AN INTERIM REPORT: YOUNG GIOVANNI MORELLI AND ART CONNOISSEURSHIP

How to sum up the unfolding panorama of Giovanni Morelli swirling across, with his Sturm und Drang verve, the sceneries of pre-revolutionary Biedermeier Germany and of (again) pre-revolutionary France, and soon also of Italy?

All-sided receptiveness met stimuli from all sides.

Resulting with young Morelli, ecstatically enjoying the feast of life (not without experiencing also sober and also most gloomy moments);(47) and with him feeling, rather constantly: the urge to ridicule what was to be ridiculed from the Sturm und Drang perspective of a gifted and intelligent young student. Who was passionate, cheerful, hilarious, and ecstatic as to everything made of ›flesh and blood‹ and as to everything radiating vitality as well as ingenuity; and who showed averse to everything dull, pedantic, pretentious and boring.

Among those things to be ridiculed, from the perspective of 24-year-old Morelli, was idle talk, particularly idle talk on artistic things; and among these things was also and particularly foolish art connoisseurship.

Not actual, not real connoisseurship, which was represented mostly by real and ingenious artists, and above all represented by Genelli; but it is crucial to say that Giovanni Morelli, at age 24, did not aim to become a connoisseur of art at all. Art connoisseurship was something he did observe and something that he, with Genelli, did ridicule, as far as it deserved to be ridiculed. And real connoisseurship was to be considered as being part of a general knowing of how to live. Including a being able to appreciate art which, due to its being ingenious and vital, was indeed worth of being apprecicated.

While his main interest was directed to the art of literature. And while, still, he had not given up his actual study of the natural sciences, which, however, had been outshadowed by his passion for literature already.

Genelli had become his mentor, his friend, and as a friend also his primal mentor. But one should not be mistaken to think that Genelli was his only mentor or teacher.

Beside the fact that Morelli had met Genelli rather at the end of his Munich stay, all-sided receptiveness meant, and this applies for Morelli throughout his life, that he was able to learn from everyone. From his friends as well as from his adversaries. And if Genelli, indeed, was his one and primal mentor as regards almost everything, one should not be mistaken, that Morelli did not also learn, as he did learn from Genelli about artistic things on all levels, from other artists, namely painters (since no less than seven other painters had been members of his beloved Munich lunch club, and this did not even include painter Carl Adoph Mende who was to become also a friend).(48)

At Paris Morelli had made also the acquaintance of Franz Xaver Winterhalter.(49) And this particular painter, a portrait artist to the establishment, might have been interesting for Morelli, just because Winterhalter was a portrait artist to the establishment. In other words: somebody who had met many interesting people, people interesting to meet and to observe as characters. As also portrait artist Franz von Lenbach, in later years a friend of Morelli,(50) had met and portrayed the European establishment and the high society.

And Morelli, as much as he also might have been interested in Winterhalter and Lenbach as artists, was also someone interested, as a man and as a writer, in the study of characters, of people, in a word: of human nature.

Giovane fumatore by Jan Miense Molenaer,

from Morelli’s own collection (picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it),

a smoker as young Giovanni Morelli has been himself

(compare GM to Bonaventura Genelli, 5 April 1840)

(Source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 266)

Having said that young Morelli was far from wanting to become a connoisseur of art, we face, with our first interim report, a Morelli still preparing, unvoluntarily, to become a connoisseur of art. With him being interested also in everything else, and with him bringing, much later, an assortment of ideas, eclectically assorted and synthesized, into connoisseurship.

Lacking was, nonetheless, the incentive to do what, later he was to do, also due to several incentives: Lacking, in 1840, was the actual need ›to know it better‹, which later was to become the essence of scientific connoisseurship: the aim to know it better, that is to know it with more certainty, that is: to attain a higher degree of certainty as to attributions.

But as long as Morelli regarded art connoisseurship as the subject matter of a comedy, he might have been focussed primarily on foolish connoissseurship, and only indirectly on real ingenious connoisseurship, not to mention the problem to know it, as far as attributions of works of art were concerned, better (which he might have, at the time, rather regarded as a pretentious doing).

In sum: scientific connoisseurship, understood as he did understand it later, was then, in 1840, certainly not (or not very often) on his mind.

Still, in 1840, he already had gathered several stimuli that we are to count among the stimuli that, later, he was to synthesize as a specific method. And while a general visual apprenticeship might have contributed to his later doing generally, we should confine ourselves here to name the more specific stimuli:

above all the various classificatory systems of the natural sciences, meant to become a general backdrop of his later thinking, although never transferred literally to art connoisseurship; a scientific culture also that expected a general commitment to a scientific ethos and to scientific standards (including the expectation that any claim should be backed up by reasons); and in addition to that: several less obvious stimuli as for example physiognomy (because early descriptions of people by Morelli are still redolent of physiognomic views),(51) that might have trained his eye for particularities of anatomy as well as his training in comparative anatomy might have trained more generally his eye for detail; and last but not least one particular stimulus: the experience of having been a sitter to various artists: because the virtually bodily experience to see one’s own body represented by various artists, imposing their invidual styles upon such representation, might also have contributed to a general sense for style, displayed by Morelli in his later years, if focussing particularly on such deliberately-unvoluntarily imposing of artistic impulses upon the representation of the human body. That, much later, were, in a context of scientific connoisseurship, to be regarded as resulting in visual properties, marginal details and clues as to the determining of authorship of works of art.

Jonathan Richardson (1665-1745)

Carl Friedrich von Rumohr (1785-1843)

Gustav Friedrich Waagen (1794-1868)

Karl Eduard von Liphart (1808-1891)

Johann David Passavant (1787-1861)

INTERIM REPORT (MORELLI AND ART CONNOISSEURSHIP) I (1833-1840)

Athanasius Raczynski (1788-1874; compare Kaiser 2010)

1833ff.: the probably first connoisseur of art Giovanni Morelli ever meets in his life (beside his Bergamo friends, the Frizzoni brothers) is Athanasius Raczynski, whom he meets in the Munich studio of Bonaventura Genelli (GM to Federico Frizzoni, 14 July 1837 (Frizzoni 1893, p. XVIII)); while studying at Munich Morelli associates with many artists and meets, above all, Genelli, who is becoming a dear friend.

1836: in his first literary work, the Balvi magnus, Morelli mentions various art historians, and among them also connoisseur [Jonathan] Richardson (Morelli 1836, p. 3; compare Anderson 1991b, p. 37; it is possible and even likely that Morelli studied also the works of Winckelmann; compare Spector 1969, p. 70).

1837/38: Morelli visits Erlangen, Nurimberg and Schloss Weissenstein at Pommersfelden (compare Bonaventura Genelli to GM, 24 December 1837; Frizzoni 1893, pp. XIXff.); before or after his Berlin stay he also sees the gallery of Dresden for the very first time; with his new friend, Erlangen professor Veit Engelhardt, he provides an article on drawings by Genelli (Engelhardt/Morelli 1839) that is probably directed against Raczyński 1839, pp. 224-227, and meant to defend or to better explain Genelli.

Christian Xeller and Mayer Carl von Rothschild (pictures: Wikipedia; ub.uni-frankfurt.de)

1838: in Berlin salons Morelli encounters (rather briefly) Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, Gustav Friedrich Waagen and Karl Eduard von Liphart; he associates with restorer Christian Xeller and keeps on corresponding with Genelli, also on connoisseurial matters. Since he is intensely associating with Bettina von Arnim, above all, he also meets, in her salon, Mayer Carl von Rothschild.