M

I

C

R

O

S

T

O

R

Y

O

F

A

R

T

........................................................

NOW COMPLETED:

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

INDEX | PINBOARD | MICROSTORIES |

FEATURES | SPECIAL EDITIONS |

HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION |

ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP |

SEARCH

........................................................

>MICROSTORIES

>MICROSTORIES

- Richard Serra

- Martin Scorsese

- Claude Simon

- Sunshine

- Werner Herzog

- The Creation

- Marcel Duchamp

- Nino Rota

- Wölfflin and Woolf

- Hansjörg Schneider

- Kraftort Arkadien

- Visual Biography

- Schlaraffenleben

- Die Geisteswissenschaften

- The Voyeur

- Buzzword Sustainability

- Paul Verlaine

- Tao Yuanming

- New Beginning

- Seneca

- Still Lifes

- Charles Baudelaire

- Frédéric Chopin

- The Art History of Sustainability

- Wang Wei

- Solarpunk

- Historians of Light

- Lepanto

- Renaturalization

- Plates

- Snow in Provence

- Learning to See

- Picasso Dictionaries

- Peach Blossom Spring

- Picasso Tourism

- Tipping Points

- Sviatoslav Richter

- Weather Reports

- Treasure Hunt

- Another Snowscape in Picasso

- Picasso in 2023

- Dragon Veins

- The Gloomy Day

- The Art of the Pentimento

- Reforestation

- The Status of Painting

- Emergency Supply

- Punctuality

- Watching Traffic

- Zhong Kui

- How Painting Survived the 1990s

- Confirmation Bias

- Sustainability and Luxury

- Garage Bands

- Picasso and Artificial Intelligence

- Eyes of Tomorrow

- Picasso in 2023 2

- Gluing Oneself to Something

- Suburbia

- Bamboo

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 1

- Interviews with Bruegel

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 2

- Coffee & Sugar

- Bamboo 2

- Picasso in 2023 3

- Sustainability and Carpe Diem 3

- Cherry Orchard

- Old Magazines

- Chance

- Nick Drake

- Harlequin

- The Smartphone & the Art Book

- Atlas Syndrome

- The Kitchen

- Atlas Syndrome 2

- Consideration

- Tori Amos

- School

- Orchard Auctioning Day

- The Hundred Years’ War

- Sócrates

- Chameleon

- Nefertiti Bust

- Picasso as a Computer

- Sunflowers

- Philemon & Baucis

- Ode to the Radio

- Childhood

- Wimmelbild

- Restitution

- Nick Drake 2

- Wishful Thinking

- Sundays

- The Independent Scholar

- September

- The Fisherman by Pirosmani

- Microadventure

- Sociology

- Salvator Mundi

- Chillon

- Appassionata

- Amber

- Homer

- Berlin

- Planet Walk

- Improvisation

- Seeing Picasso

- These Nice Kids

- Robber

- The One

- The Sea Turtle

- Zoo

- Through the Hush

- Wunderkammer

- I Do Not Seek, I Find

- Shopping Mall

- Food Hamper

- The Secretary

- This Gate

- Nor Rainy Day

- House on a Hill

- Beautiful Island

- Second-hand Bookstore

- Flat

- Slap in the Face

- Serra, Wenkenpark

- Apologies

- The Bells

- Nordmann Fir

- Picasso Wanting To Be Poor

- Picasso, Pirosmani

- A Brief History of Sculpture

- 24 Sunsets

- Rusty Phoenix

- Glove

- Wintry Stanza

- A Song

- Like A Beatle

- Catching An Orange

- Solar Bees

- Permaculture

>FEATURES

>FEATURES

- Van Gogh On Connoisseurship

- Two Museum’s Men

- Ende Pintrix and the City in Flames

- Titian, Leonardo and the Blue Hour

- The Man with the Golden Helmet: a documentation

- Un Jury d’admission à l’expertise

- Learning to See in Hitler’s Munich

- Leonardo da Vinci and Switzerland

- The Blue Hour Continued

- The Blue Hour in Louis Malle

- Kafka in the Blue Hour

- Blue Matisse

- Blue Hours of Hamburg and LA

- A Brief History of the Cranberry

- The Other Liberale in the House

- The Blue Hour in Raphael

- Who Did Invent the Blue Hour?

- Monet on Sustainability

- Velázquez and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Guillaume Apollinaire

- Van Gogh on Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Marcel Proust

- Picasso and Sustainability

- The Contemporary Blue Hour

- The Blue Hour in 1492

- The Blue Hour in Hopper and Rothko

- Hopper and Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Ecotopia

- The Hour Blue in Joan Mitchell

- Explaining the Twilight

- The Twilight of Thaw

- The Blue Hour in Pierre Bonnard

- Explaining the Twilight 2

- Picasso on Stalin

- Rubens on Sustainability

- The Salvator Mundi in Bruegel and Rubens

- The Blue Hour in Leonardo da Vinci and Poussin

- The Blue Hour in Rimbaud

- Faking the Dawn

- Frost and Thaw in Ilya Ehrenburg

- Picasso, Stalin, Beria

- Picasso, Solzhenitsyn and the Gulag

- Shostakovich on Picasso

- Hélène Parmelin in 1956

- Historians of Picasso Blue

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 1

- The Blue Hour in Caravaggio

- Picasso Travelling to Moscow 2

- Picasso, the Knife Game and the Unsettling in Art

- Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Slavery

- Picasso Moving to the Swiss Goldcoast

- The Blue Hour in Camus

- The Blue Hour in Symbolism and Surrealism

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element

- Exhibiting the Northern Light

- Caspar David Friedrich in His Element 2

- Robert Schumann and the History of the Nocturne

- The Blue Hour in Robert Schumann

- Caspar David Friedrich and Sustainability

- The Twilight of Thaw 2

- Multicultural Twilight

- The Blue Hour in Anton Chekhov

- The Blue Hour in Medieval Art

- Twilight Photography

- The Blue Hour in Bob Dylan

- Iconography of Optimism

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

>SPECIAL EDITIONS

- Visions of Cosmopolis

- Mona Lisa Landscapes

- Turner and Ruskin at Rheinfelden

- Painters On TV & On TV

- Spazzacamini in Art

- A Last Glance at Le Jardin de Daubigny

- The Experimental Cicerone

- A Dictionary of Imaginary Art Historical Works

- Iconography of Blogging

- Begegnung auf dem Münsterplatz

- Cecom

- Das Projekt Visual Apprenticeship

- Those Who See More

- A Fox on Seeing with the Heart

- Sammlung Werner Weisbach

- Daubigny Revisited

- Some Salvator Mundi Microstories

- Some Salvator Mundi Afterthougths

- Some Salvator Mundi Variations

- Some Salvator Mundi Revisions

- A Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- A Salvator Mundi Puzzle

- Unknown Melzi

- Francis I and the Crown of Charlemagne

- From Amboise to Fontainebleau

- Drones Above Chambord

- Looking Back At Conques

- Flaubert At Fontainebleau

- Images of Imperial Ideology

- The Chronicles of Santa Maria delle Grazie

- Seeing Right Through Someone

- Melzi the Secretary

- Eying Glass

- A Foil to the Mona Lisa

- A Renaissance of the Cartoon

- Sketching a Family Tree

- Venetian Variations

- A Brief History of Digital Restoring

- A Consortium of Painters

- Leonardeschi and Landscape

- A Christ in Profile

- Learning to See in Spanish Milan

- A History of Gestures

- Leonardo and Josquin

- A Renaissance of the Hybrid

- Suida and Heydenreich

- The Watershed

- Three Veils

- From Beginning to End

- Connoisseurship of AI

- Twilight and Enlightenment

- The Blue Hour in Chinese Painting

- Dusk and Dawn at La Californie

- Iconography of Sustainability

- The Blue Hour in Goethe and Stendhal

- The Sky in Verlaine

- The Blue Hour in Paul Klee

- Iconography of Sustainability 2

- The Blue Hour in Charles Baudelaire

- From Bruegel to Solarpunk

- Some Salvator Mundi Documentaries

- Some More Salvator Mundi Monkey Business

- The Windsor Sleeve

- Brigitte Bardot’s Encounter with Picasso

- Art Historians and Historians

- A Salvator Mundi Chronicle

- The Salvator Mundi and the French Revolution

- The Fontainebleau Group

- The Encounter of Harry Truman with Pablo Picasso

- The Fontainebleau Group Continued

- The Windsor Sleeve Continued

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 1

- Some Salvator Mundi Resources

- A New Salvator Mundi Questionnaire

- The Woman in Picasso

- The Yarborough Group

- Melzi, Figino and the Mona Lisa

- The Yarborough Group Continued

- A Salvator Mundi Global History

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art

- The Salvator Mundi in Medieval Art 2

- The Salvator Mundi in Early Netherlandish Painting 2

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

>HISTORY AND THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION

- The Mysterious »Donna Laura Minghetti-Leonardo«

- Assorted Demons of Connoisseurship

- Panofsky Meets Morelli

- Discovering the Eye of Sherlock Holmes

- Handling the Left-handed Hatchings Argument

- Visual History of Connoisseurship

- Alexander Perrig

- Connoisseurship in 2666

- What Postmodernity Has Done to Connoisseurship

- Dividing Four Fab Hands

- A Leonardesque Ambassador

- Test Cases in Connoisseurship

- A Raphael Expertise

- How to Tell Titian from Giorgione

- Louise Richter

- The Unique Property in the History of Connoisseurship

- An Expertise by Berenson

- The Book of Expertises

- An Album of Expertises

- An Expertise by Friedländer

- A Salvator Mundi Provenance

- How to Tell Leonardo from Luini

- An Expertise by Crowe and Cavalcaselle

- An Expertise by Bayersdorfer

- An Expertise by Hermann Voss

- An Expertise by Hofstede de Groot

- Leonardeschi Gold Rush

- An Unknown »Vermeer«

- An Expertise by Roberto Longhi

- An Expertise by Federico Zeri

- A Salvator Mundi Geography

- A Salvator Mundi Atlas

- The Bias of Superficiality

- 32 Ways of Looking at a Puzzle

- James Cahill versus Zhang Daqian

- Five Fallacies in Attribution

- On Why Art History Cannot Be Outsourced to Art Dealers

- On Why Artificial Intelligence Has No Place in Connoisseurship

- Salvator Mundi Scholarship in 2016

- Leonardo da Vinci at the Courts

- The Story of the Lost Axe

- The Last Bruegel

- A Titian Questionnaire

- On Where and Why the Salvator Mundi Authentication Did Fail

- The Problem of Deattribution

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

>ETHNOGRAPHY OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP

AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

........................................................

***

ARCHIVE AND FURTHER PROJECTS

1) PRINT

***

2) E-PRODUCTIONS

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

FORTHCOMING:

***

3) VARIA

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

........................................................

***

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI MONOGRAPH

- The Giovanni Morelli Monograph

........................................................

MICROSTORY OF ART

ONLINE JOURNAL FOR ART, CONNOISSEURSHIP AND CULTURAL JOURNALISM

HOME

The Giovanni Morelli Visual Biography

THE GIOVANNI MORELLI VISUAL BIOGRAPHY Visual Apprenticeship II  |

If Morris Moore, the owner of the much debated Apollo and Marsyas (now in the Louvre and by some called Apollo and Daphnis), had known that, as of today, Morelli is being considered as representing scientific connoisseurship, Moore would probably called out that Morelli, in his eyes, was nothing but a picture dealer (Käss 1987, p. 158). Picture dealer, and Moore, as we have to face situations »fraught with ambiguousness and double-dealing« (Donata Levi) as for this chapter, we would’t be able to prove Moore completely wrong.

(Picture: louvre.fr)

It was the middle aged Morelli who had to learn a lot, and he had to learn this lot fast indeed. Having not learned at all how to succesfully deal with pictures; nor having learned in any way how to protect the cultural heritage of Italy. For both activities connoisseurial skills were necessary, and it was a Morelli facing exactly this two tasks who felt it to be necessary to think about connoisseurial practices that guaranteed a sound and reliable judgment as to the authors of pictures.

And while his visual education thus was progressing, he was to learn how to maneuver while doing both: protecting the cultural heritage of his home country, and dealing with (and not only minor) pictures to keep solvent.

ONE) THE DETAIL AND THE WHOLE, THE NATION AND THE ART MARKET OR: VIEWS FROM THE NIGHTSIDE OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

VISUAL APPRENTICESHIP II:

(ONE) THE DETAIL AND THE WHOLE, THE NATION AND THE ART MARKET OR:

VIEWS FROM THE NIGHT SIDE OF CONNOISSEURSHIP

(TWO) ILLUSIONS, CERTAINTIES AND CERTAIN CONVICTIONS OR:

WORLD FAIR OF CONNOISSEURSHIP – THE »HOLBEIN-STREIT«![]()

Pictures by German painter

Johann M. Rugendas (1802-1858)

that also influenced

no other than Charles Darwin,

might perhaps also have influenced

Giovanni Morelli, in his using

of the metaphor of an ›American jungle‹,

if referring to the world of art

(see GM to Jean Paul Richter, 5 July 1877 (M/R, p. 7f.))

(picture: faz.net/Johann M. Rugendas)

The world of art might never have looked more like a wild forest to Giovanni Morelli than at around 1860, when he began to envision himself writing on art, with one of his first projects being, on suggestion of no other than poet Alessandro Manzoni, to carry out a guide to the Pinacoteca di Brera.(1)

The now available nine-volumes catalogue to that collection, directed by Federico Zeri, does look mightily impressive. The index has Giovanni Morelli, certainly by accident, named ›Le Morlieff‹ (which he probably would have liked, and maybe adapted as another alias).(2)

But this was a wild forest, to cut one’s way through it, with axe and machete. And not really to our surprise, since Morelli knew himself, and his friend Genelli knew it also,(3) that he, Morelli, had no actual endurance to carry large projects out all by himself – and not really to our surprise this early connoisseurial project was never to see the light of day.

The materials necessary, years later, were returned to the Brera. And what Giovanni Morelli (or others with him) had envisioned, had been a guide, and probably not an actual large catalogue, or inventory, or catalogue raisonné.(4)

(Picture: domusweb.it)

Although Giovanni Morelli, generally, in science as in art, was no actual systematist (since he was lacking patience, discipline, endurance), he still could look at things with the eyes of a systematist. Which means that in the individual work of art, for him, a problem of taxonomy and of classification shined out; and in the detail, seen as a substructure of a work of art, the same problem shined out, as well as a possible clue to solve that very problem.

Morelli could see art connoisseurship against the backdrop of the natural sciences, and against the backdrop of taxonomy and classificatory systems very in particular; and certainly he did see, to probably varying degree over the years, the Kunstwissenschaft he envisioned (that was to be built on connoisseurship), in analogy to the model of 19th century natural history, its species and subspecies, types and subtypes, and, in sum, classificatory systems. And the history of art, of artist, could also be seen in analogy to natural evolution, with pupils, naturally, learning from their masters, but naturally also developing own ways of seeing, resulting with new nuances in style and with completely new stylistic paradigms.(5)

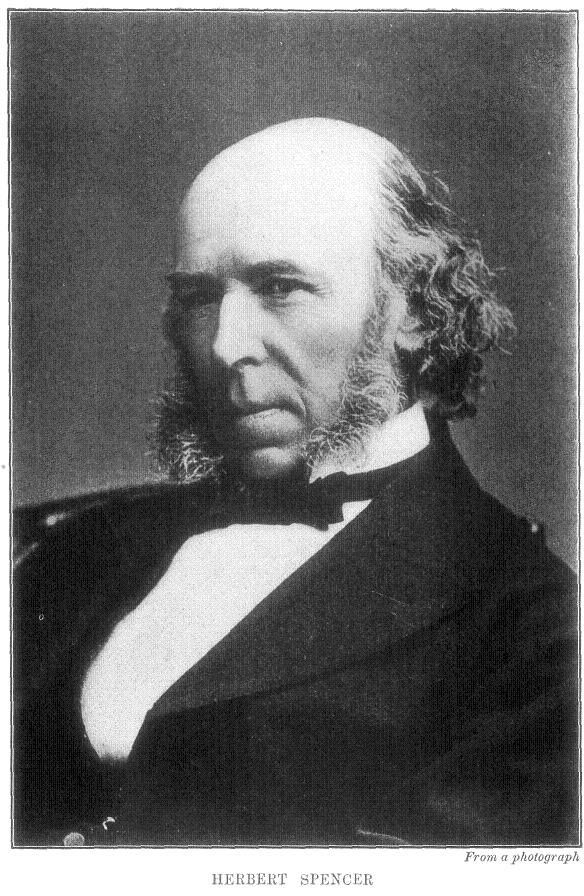

In 1868 Herbert Spencer,

the popularizer of positivism,

travelled to Italy,

and subsequently thought about

the classification of art works

according to a (rather simple) system

(see Duncan (ed.) 1908, p. 375;

the criteria being

Subject, Form, Color and Shade)

THE BEGINNING OF A JOUST

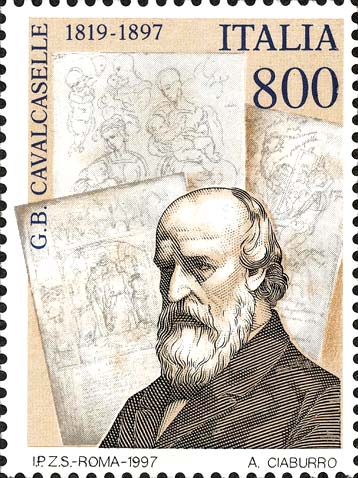

Still – Morelli could not be, in the full sense of the word, a systematist. And against this backdrop the quintessential rivalry with another quintessential Italian connoisseur of the 19th century, namely with Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, has also to be seen. Which means that we should also keep in mind, albeit the rivalry was indeed the rivaly of mainly two main protagonists with their respective circles – one making a case for scientific connoisseurship, and another remaining rather indifferent as to this very ambition – there was a third position that remained empty: and this was the position of the systematist that Morelli’s vision did imply. And that himself he could not be. Since full system-building could not be managed by him who had given up a possible career in science since he could not invest several years of his life, simply observing the anatomical shapes of a may bug.(6)

The psychology of the Morelli-Cavalcaselle relationship indeed included something of this frustration, resulting from the fact that Morelli aimed at something that himself he could only partially fulfill and hence also only partially represent. And for him there was not only a rival to polemicize against – there was someone who remained indifferent and also did not help him, in spite of, due to Morelli’s lack of patience and discipline, help was actually needed. If one wanted – and this was another crucial point – scientific discipline in connoisseurship to be implemented.

While Giovanni Morelli, art connoisseur, owed much to Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, the latter owed rather little to Morelli. Because Morelli needed Cavalcaselle to become Lermolieff/Morelli, that is: a sort of ›Anti-Cavalcaselle‹, while Cavalcaselle did not need Lermolieff/Morelli to become Cavalcaselle, at least not the one Cavalcaselle that was to publish books in collaboration with Joseph Archer Crowe. And if there was something in later years that might have frustrated Morelli even more than having to face the art historical views of his opponent (and to see others to ascribe definatory power to his opponent and authority to his views), it was that Crowe and Cavalcaselle seemed not to take notice of Lermolieff/Morelli.(7)

As strange as it might sound: the relation between Giovanni Morelli and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle has never been studied in depth. Many aspects of that relationship have been forgotten (or have never been widely known), beside that the relationship as such has been seen, and is: of symbolical importance. And if it would be only about impersonal questions, questions of attributions in regard to Italian art, one might lean back and think that it would be enough to review and weight soberly put forth arguments, brought forward by either side, by either camp.

But the relationship between Morelli and Cavalcaselle goes deeper in that one side (Morelli) was occasionally claiming that the other side had to put forward sober arguments at all, if it wanted to be taken seriously (by the Morellian camp), because, in his, Morelli’s view, connoisseurial questions had to be dealt with rationally. Scientifically. And, necessarily, sober arguments had to be put forward.

This was the claim. Although Morelli hardly lived up to this ideal, to his own ideal, one might add, generally or all the time. And to study the Morelli-Cavalcaselle relationship is not only about reasons or arguments, but about the question to what degree connoisseurship was and is to be organized (and maybe institutionalized) rationally, scientifically at all.

Beyond that, and beside that both men represented, as human beings, opposits in many regards, the rivalry between both (it was a rivalry, because Morelli wanted it, defined it, and staged it as a rivalry) bears not only on questions of attribution, but also on principles of restoration of works of art, and not the least: on the regulations of the art market and the protection of cultural heritage.

The antagonism stretched to all of these fields as, again seen from the Morellian side, a rivalry of reputation and influence. In a word: it was, for Morelli, and he did declare it openly at least to his one pupil Jean Paul Richter, a struggle about definatory power. Mainly, but not exclusively as to the writing of the history of Italian art (and the question upon which principles such a history had to be written, since Morelli himself, did not write such a history), and as to the principles of restoring and of regulating the art market (in which both, Morelli and Cavalcaselle were also involved).

This struggle about definatory power, at least from Morelli’s side had also an existential aspect, because not having written a history of Italian painting, questioning the definatory power of Crowe and Cavalcaselle (and of others) was simply, beyond being a politician, what Giovanni Morelli had achieved intellectually in life (and losing this struggle must have meant for him: having to consider his intellectual life achievements as a failure).

Since the looking at such a multilayered confrontation, at such a deep and continuous disagreement, even it is situated in the past, does tell much as to the mechanisms of power within the scene of art history and connoisseurship even today, and it is perhaps not all too surprising that the relation between Morelli and Cavalcaselle has never been studied in depth. Not because there would not be much to be revealed. But because, and in a certain sense, there would be too much (reflecting today practices and today mechanisms of power).

THE HISTORY OF A DISAGREEMENT:

GIOVANNI MORELLI AND GIOVANNI BATTISTA CAVALCASELLE

(Picture of Cavalcaselle: artearti.net)

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna della Rondine

Andrea Busati, The Entombment (picture: fineartamerica.com)

Sir William Boxall and Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (pictures: npg.org.uk)

Sir Austen Henry Layard (picture: npg.org.uk)

›The so-called portrait of Gattamelata‹

(Picture: doullbooks.com)

1857: 16 October: Morelli has heard of »un certo Cavalcaselle veneziano« (GM to Niccolò Antinori, 16 October (Agosti 1985, p. 33); Cavalcaselle notes for the very first time the name of Morelli, as a friend of Otto Mündler (Levi 1988, p. 110); Cavalcaselle, at that time, and supported by Austen Henry Layard and Charles Lock Eastlake, is collecting data which, subsequently, he is going to use in his cooperation with Joseph Archer Crowe (Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 181).

1858: Cavalcaselle travels in Italy with Eastlake; Mündler supports Morelli in that he his naming him, i.e. his views, in his travel diary, directed to the officials of the London National Gallery (in 1858 however, Mündler is also being dismissed from acting as a travelling agent for the National Gallery).

1861: probably not their first meeting, the common 68 days trip of Cavalcaselle and Morelli to the Marche and to Umbria takes place (but Cavalcaselle does not act, as Layard later has it, as Morelli’s ›secretary‹): see Levi 2002; and see Levi 1988, p. 153f.); 16 June: in a letter to Antinori (Agosti 1985, p. 39) Morelli speaks of that trip and of the ›patience of Job‹ necessary to endure Cavalcaselle; Cavalcaselle does meet Joseph Archer Crowe again, at Lipsia.

1862: in the summer Cavalcaselle offers his services to the Minister of Education Carlo Matteucci, making also a series of proposals as to the conservation of the national art heritage (Levi 2005, p. 43).

1862: fundamental disagreement over the export of the Madonna della Rondine by Crivelli from Italy (today National Gallery of London; see picture on the left; and see Smith et al. 1989, Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 182, and Levi 2005, p. 43f.), which Morelli does support (perhaps only after assuming that it could not be prevented) and Cavalcaselle seeks (at first, and probably to Morelli’s bewilderment, seemingly successful, but in the end in vain) to prevent; possibly and very likely the transaction has also a direct or indirect financial implication for Morelli who is in constant need of money throughout the decade of the 1860s (for details see text below, with note 24, below) and had to maintain his status among the advisors of the foreign museum’s officials; also disagreement over the attribution of a painting owned by Layard that Cavalcaselle attributes to Cima, and Morelli, on the basis of (wrongly) deciphering the cartellino, to Sebastiano del Piombo (GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 March 1878 (M/R, p. 36; Morelli remembers the year of 1858); see also Richter/Morelli 1878, Anderson 1987b, note 4 on p. 127 (wherein the date is corrected), and compare now Anderson 2014, p. 21 and 67 (note); the painting, in the National Gallery of London, is today attributed to Andrea Busati; picture on the left).

1862: Morelli sells his Lotto double portrait (above) to the National Gallery of London, and subsequently refuses to have his name as the seller erased (Levi 2005, p. 44).

1863: Cavalcaselle has reworked and published his proposals made to Matteucci in the summer of 1862 (see Levi 2005, p. 52, note 67); disagreement over regulations of the art market (see Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 182, note 52); disagreement over principles of restoration; Layard confirms Morelli as his advisor, meant also to buy works of arts for him; Morelli, on his part and as a politician, is in need of Layard’s support in helping to manage the crisis of the Lombardic silk industry in the wake of the pebrina disease.

1864-66: Crowe/Cavalcaselle 1864-1866; Layard sends the two first volumes as a gift to Morelli (Gibson-Wood, 1988, p. 196)

1865: the clear-sighted director-to-be of the National Gallery of London William Boxall considers both Morelli and Cavalcaselle as ›enemies of our carrying away of works of arts from Italy‹; 19 May (Gibson-Wood 1988, p 331, note 36): Morelli utters a favourable opinion as to Cavalcaselle to Layard (who is respecting both, and had also been a supporter of Cavalcaselle; the third volume of Crowe and Cavalcaselle’s collaborative work being dedicated in 1866 to him ; see Gibson-Wood 1988, pp. 196, 215).

1866: in a letter from Florence to Mündler Morelli mentions that, Cavalcaselle, ›the [grumpy] laybrother‹ had visited him (GM to Otto Mündler, 20 June 1866 (Kultzen 1989, p. 398)), seeking for help, not realizing however, according to Morelli that he, Morelli, could do nothing for him (it is unknown to what purpose, but the context probably is the 1866 war against the Austrians and the role of both men therein).

1867: Cavalcaselle, who has become inspector of the Bargello, consults also the National Gallery under Boxall (according to Levi 2005, p. 44 Cavalcaselle’s business contacts with the foreign market appear limited to this one relation; see also ›1869‹); Morelli, on his part, is offering »both help and paintings« to Boxall, Burton (Eastlake’s successor) and private collectors (Levi 2005, p. 44).

1868: Morelli utters a very unfavourable opinion as to Cavalcaselle (GM to Austen Henry Layard, 5 January 1868, (Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 331, note 36; compare also Anderson 1991a, p. 488).

1869-76: Crowe/Cavalcaselle 1869-1876

1869: The journal of Boxall mentions Cavalcaselle as a consultant, speaking also about Morelli (Levi 1988, p. 324)

1871: Crowe/Cavalcaselle 1871.

1873: Morelli, as Crowe and Cavalcaselle, stays in Vienna where the world exhibition takes place (compare Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 277).

1875: Cavalcaselle assumes office as a general inspector of the Italian museums.

1876: disagreement over picture cleanings; Morelli’s intervention (as, beforehand, much luck; see Seybold 2014a, p. 167, with note 287) prevent the export of Giorgione’s Tempesta.

(Picture: archive.org)

1877: Crowe/Cavalcaselle 1877.

1878: »Der einzige Weg, der aus diesem Kunstchaos uns heraushelfen kann, und der mit der Zeit uns zur Kunstwissenschaft zu führen verspricht, der einzige Weg, meine ich, ist eben der des strengen Studiums der Form […]. Diese Methode jedoch führt übrigens zum gewünschten Ziele nur nach langjährigen Studien in Bildergalerien, und nachdem sich einer im grossen und ganzen mit den verschiedenen Kunstschulen eines Landes vertraut gemacht, so dass im Grunde die von mir angeführte Methode nur dazu hilft und helfen kann, das Werk eines Meisters von dem seiner Schüler und Nachahmer zu unterscheiden. Und das ist gerade der Felsen, an dem das Schifflein der meisten Kunstjünger scheitert. Der alte Cavalcaselle z.B. weiss fast nie den Meister vom Schüler und Kopisten zu sondern, er tappt eben wie die anderen Kunstgenossen im Finstern herum.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 20 March 1878 (M/R, p. 34f.))

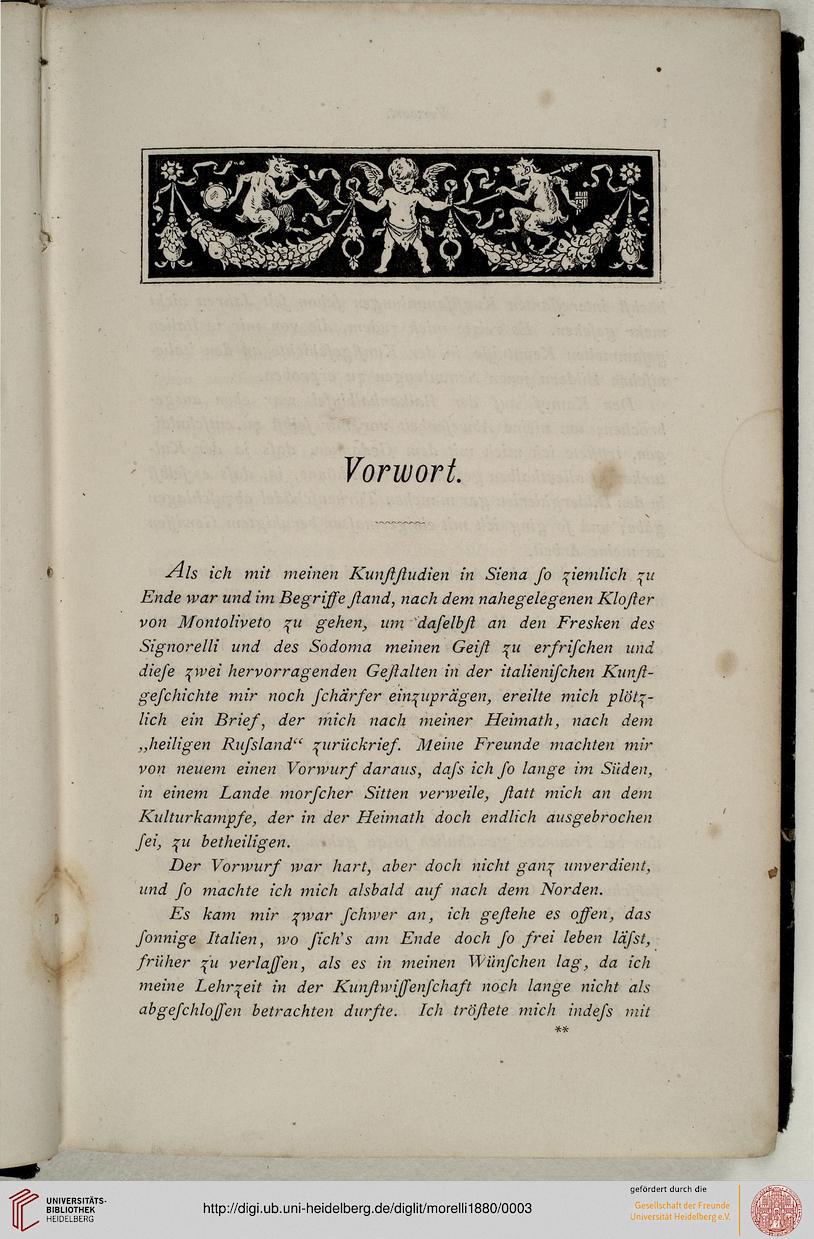

Translations

1880: Morelli publishes his book on the galleries of Dresden, Munich and Berlin (Morelli 1880), which also can be interpreted as a partly furious, partly ironical attack on the definatory power of Crowe and Cavalcaselle; it is causing furious reactions among supporters of Cavalcaselle such as for example Karl Eduard von Liphart (see Käss 1987, p. 171), who is also seen by Morelli as a longtime antagonist.

The beginning of the notoriously famous Vorwort of Morelli 1880

(picture: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de)

1880: »Nun frage ich Sie, war es nicht meine Pflicht, denjenigen Leuten, die sich der Führung der Historiographen der ital. Kunst zutrauensvoll überlassen, zu beweisen, dass erstens jene Herrn [Crowe and Cavalcaselle] in der Kunstkenntnis sehr schwach sind, und zweitens dass dieselben ihren Mangel an wahrem Wissen durch eine höllische Charlatanerie zu verdecken trachten? Dass Cavalcaselles Kenntnisse und Geschmack in der Kunst nicht weit her sind, beweisen, glaube ich, zur Genüge seine Urteile über den Moretto, den Giorgione, den Lo. da Vinci, den Tizian in Dresden – über den Pesello in den Uffizien, den Tizian in Darmstadt, den Giorgione in Madrid usw. – Dass er auch ein Charlatan ist, leuchtet klar aus seinen Attributionen des sog. Mantegna in München, aus der des Torbido in den Uffizien, aus der des Calderari in der Ambrosiana, ferner daraus, dass er ohne allen Grund den Giofrancesco da Tolmazzo dem G. A. da Pordenone zum Lehrer gibt, in dem Gemälde aus der Spätzeit des Tiziano in München Pinselstriche von Rubens oder von v. Dyck erkennen will, zum Bilde Lotto’s in der Borghese Galerie, vom Jahre 1508, die Skizze von Palma Vecchio geliefert zu sein [probably: haben] behauptet, im Bilde Tizians (im Vorraum der Sakristei der Salute in Venedig) Einflüsse Fra Bartolomeos sehen möchte, usf. Ich könnte noch dutzende Beispiele der Art anführen. Nun frage ich Sie, ist es nicht die heilige Pflicht eines Kritikers, das Publikum vor solchen arroganten Spiegelfechtereien zu warnen? Wenn einer in einem ganz und gar übermalten Wandgemälde, wie die Propheten und Sibyllen in der ›Pace‹ zu Rom sind, im Gefälte noch die Pinselstriche von Timoteo Viti zu erkennen vorgibt, kann man solche Frechheit mit einem andern Worte bezeichnen, als mit dem der Charlatanerie? Finden Sie noch immer, dass ich zu strenge gegen jene Herrn verfahren bin? Cavalcaselle zitiert Mündler, dem er gar manchen Fingerzeig verdankte, nur da, wo er ihm eins anhaben kann – ein solcher Gesell verdient keine Rücksicht, und habe ich einen Fehler begangen, so ist es, ihn nicht tüchtiger geschüttelt zu haben, als ich dies tat.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 10 December 1880; compare also Anderson 1991a, p. 557, and Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 231)

1882:»Was nun speziell das sog. Porträt des Gattamelata des Giorgione in der Uffiziengalerie betrifft, so bin ich dabei meiner Sache sicher, und zweifle nicht, dass mein Urteil über jenes Bild mit der Zeit von allen wird gebilligt werden, die eingehender dem Studium der veronesischen Malerschule sich widmen werden. Das Urteil des Cavalcaselle ist wahrhaft läppisch zu nennen. Ich kenne seine Logik ganz wohl und könnte dieselbe mit Dutzenden von Beispielen verdeutlichen. Bei Beurteilung jenes Bildes mag seine Argumentation ungefähr folgende gewesen sein: Dies Porträt ist nicht von Giorgione, aber doch ihm zugeschrieben –, Mündler gibt es einem Veroneser; also Giorgione einerseits, andererseits Caroto, ein Veroneser. Vereinen wir beide Ansichten und schreiben wir [es] daher dem Torbido zu, der, nach Vasari, ja ein Schüler des Giorgione war und dabei auch aus Verona ist. Das ist aber doch wahrlich keine ernstliche Kritik sondern Charlatanerei. Wie soll man auf diesem Wege je zu einer positiven Kunstwissenschaft gelangen?«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 28 February 1880)

»Was Sie mir über die von Waagen und Cavalcaselle getauften Bilder in der Liverpoolsammlung sagen, hat mich gar nicht in Erstaunen gesetzt, ist mir ja die Weisheit der beiden Herren sattsam bekannt. Je mehr Sie dem Cavalcaselle näher treten werden, desto mehr werden Sie mir zugestehen müssen, dass ich den Charlatan mit Glacéhandschuhen behandelt habe. Nach der Herausgabe seines Raphaels werden übrigens selbst die Berliner, die an ihm eine Stütze gegen den verdammten Lermolieff zu haben glaubten, ihn nicht mehr halten können. Mit Cavalcaselle stürzen aber zugleich die andern Blinden in die Grube: Jordan, Bode, Lippmann, Meyer und Henry Wallis und wie die Anhänger alle heissen.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 26 June 1884)

1882-1885: Crowe/Cavalcaselle 1882-1885 (two volume monograph on Raphael).

1884: Morelli’s apprentice Jean Paul Richter (see Seybold 2014a), intellectually equipped by Morelli, does become more and more involved in dealing as he is becoming a standard bearer of Morellian connoisseurship (and it is also Richter who will become the later model as for being a marchand amateur for Bernard Berenson in the 1890s).

1886: furious comments by Morelli as to Cavalcaselle acting as general inspector (Gibson-Wood 1988, p. 186).

1887: »Und wie steht es mit Ihrem Artikel für die ›Academy‹ [The Academy]? Haben Sie denselben noch nicht abgesetzt, so wäre es gut, wenn Sie darin bemerken wollten, dass die Hauptgegner Lermolieff’s doch eigentlich nur die Anhänger Cavalcaselle’s sind wie Bode, Jordan, Müntz u. Konsorten.«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 4 April 1887)

Translations

INTERIORS AND SHELTERS

The Sala Botticelli today (picture: uffizi.org)

If the world of (Italian) art seemed to be an ›American jungle‹, presenting itself ins its virgin-like purity to the eyes of a young scholar – men had also hedged this jungle.

Vasari, above all, due to his imprudence, but also posterity, in its blindly-foolish ludicrousness (and following Vasari).

Resulting with the fact that it might seem alluring to explore that jungle and to get to its innermost sanctuary. But there was also a thorny hedge that seemed to prevent a young scholar from even entering that wild forest.

But the thought of treasures, perhaps to be found within that jungle, would still attract a young scholar to enter that jungle.

This was, roughly, how Giovanni Morelli was to elaborate on the metaphor of the forest in 1877.(8) And if we keep the picture and try to evaluate Morelli’s own first explorations into that jungle, we become aware that it was, obviously, also about glades, about shelters and about man-made buildings, that is: about interiors that could work as shelters.

The Sala Botticelli of the Uffizi, as it seems, was the primal and most important glade that we have to name here. Since according to tradition Giovanni Morelli it was there that he had found his compass: a method to navigate, to find his direction, to direct his comparisons – if being lost in wilderness, or stuck in thorny undergrowth.

We do not know exactly when it did occur, but the primal scene of Morellian connoisseurship, the primal scene of Giovanni Morelli finding his method, that was to become notoriously famous only much later, we might date at around 1860.(9) Its stage was the Sala Botticelli, and the only account that we have does read like the account of a heureka moment, albeit, and characteristically, without someone speaking the word ›heureka‹ out loud.

Only that this account, in hindsight, does read also as somewhat or even as all too idealized.(10)

Concerning one single picture, according that account by Jean Paul Richter, Morelli had at first recognized that there was stylistic regularity as regards the rendering of human anatomy. That is: stylistic consistency, as it were, within the single one picture.

And after Morelli had proceeded, as the solo actor on this stage of connoisseurship, and after he had compared also artist’s oeuvres, he had realized that there seemed to be also consistency in single artists’ oeuvres.

This seemed to be – then, as for the Morellian scholar later who did rely on the Morellian approach –, the one basic law: stylistic regularities seemed to exist, and therefore one could build on these regularities, on these stylistic consistencies. There seemed to be something to rely on, and one might be inclinded not to question further, or (as we do in our Giovanni Morelli Study) to question if indeed the world of art, the world of form is corresponding, in reality, to that description.

(Source: Google Art Project)

In fact nor Giovanni Morelli nor his pupils ever elaborated a analogy to the natural sciences literally. But such a backdrop did exist, also at around 1860,(11) since Morelli had gotten to known, much earlier, decades earlier, classificatory systems of the natural sciences. And it seemed that to explore the ›American jungle‹ of art, of Italian art, required a Humboldt, able to inventorize all the species found inside that jungle, and this by sticking to an able classificatory system.

A systematic approach, here, that was also inspired by many heterogenous sources, and also, if in a more vague sense, by classificatory systems of the natural sciences that built on formal consistencies, and allowed to differenciate species by typical features, and subspecies, and phenotypes of subspecies and so on.(12)

(Picture: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de;

Morelli 1890, p. 105)

If Morelli was, much later, to think back and to recall early days of his being lost in a forest, with having nothing but his intuitive sense, relying on a mere general impression of a painting, he was on the one hand recalling an allegedly ›pre-scientific‹ state of things, at around 1860, and he was recalling his uncertainty how to proceed and to decide as to authorship of single pictures.(13)

But this was not only reflecting the pre-scientific state of things, but also the pre-history of the primal scene in the Sala Botticelli of the Uffizi, or the experiences that found a more symbolical expression in that one primal scene. At any rate these inital experiences were followed by numerous expeditions, long years of studying, comparing, elaborating on – not a system, but a set of guidelines how to proceed, a set of recommendation, grown out of experience, a set of methodological principles that was to become the Morellian method.

If a heureka moment actually had occured we do not know for sure, but if, one should also oppose this moment to the overall picture, because the heureka moment might have been about finding methodological strategies that could be of help to the connoisseur of art, methodological strategies that also demanded the systematic elaborating of comparisons.

And for this, again, Giovanni Morelli simply had neither the patience, nor the actual time.

(Source: Google Art Project)

The times had changed quite radically, which meant here that there was not only little time to carry out careful studies (and to avoid imprudence), but there was also responsibility, time pressure, and a whole jungle with numerous species all awaiting to be classified, according to minor stylistic particularities, that only could be evaluated in long series of comparisons. There was the detail, in short, the whole, the time pressure, the responsibility (for himself, for the cultural heritage of Italy), and little time.

An aerial view on Bellagio (here in the foreground)

and Taronico (picture: cercaristoranti.it)

(Picture: nonsolobanca.it)

Friends of Morelli might occasionally have been puzzled (but also amused) that Giovanni Morelli, in his letters, enjoyed to picture himself as a hermit, picturing also the blissfulness of being alone among pictures and books, enjoying peace and quiet.(14)

He had been, to a certain degree, a man of leisure. But if around 1860 he was to speak of solitary studies, the sweet happiness of private life, he spoke of as something that was in danger, seemed to be gone, or actually was gone, because Morelli spoke of the sweet happiness of private life as something that he wished he had never given it up.(15)

This was also the background of Giovanni Morelli becoming the explorer of scientific connoisseurship. The leisure seemed gone, the 1860s were torn and distracted years, the sweet happiness of private studies he only could enjoy on rare occasions, and instead there was now the hornets’ nest of politics.

Blissfulness of solitary studies was now something that had to be defended.

Giovanni Morelli, if apparently only once, did also speak in parliament, since he was now the elected representative of Bergamo.(16) But on another level this meant that, beside the big stage of politics, beside the commissions, the back rooms, space had to be reorganized in general. To allow also, once in a while, a withdrawal from politics – to find blissfulness in silent studies, that also could be interpreted as needed in terms of serving one’s country. Because expertise resulted from these studies, needed to whoever was to protect the cultural heritage, who did embark on a newly organizing of that heritage and who deal with questions of artists’ education, restoration and so forth.

And if seen against this backdrop, the interiors of connoisseurship come into focus, interiors that were to become shelters, but also social places, stages, and even: secret head quarters, above all as regards the picture trade.

Giovanni Morelli had already seen a great many of connoisseurs interiors: artists’ workshops in Munich, for example (no less than seven painters had been members of his Munich lunch club), and artists had seen him, and drawn various portraits of him.

He had seen the restorers’ workshops and the picture shops; and he probably knew how for example James Hudson lived, at Turin, as an ambassador, but also as an art lover and collector.(17)

He himself had had a manor at Sanfermo (beside the family’s place, or places at Bergamo), but his Brianza manor had been replaced by a, probably more modest Taronico manor during the 1850s. His place to withdraw from politics was now situated, as were the villas of his friends, at Lake Como. And if he was heading to Taronico, taking with him documents that his political duty required him to study,(18) he was, now and then, taking also pictures with him (or had them sent to the ›rustic salon‹).(19)

And next to the Bergamo and Taronico retreats there was particularly a Milan workshop, fitting the description of an interior to the liking of a connoisseur to perfection: the workshop of Giuseppe Molteni at Milan was becoming a central place for Morelli,(20) all the more one was to find there what, above all, he did like: the blissfulness of being able to converse in small circle or only with Molteni, to discuss pictures and art matters among enthusiasts. Enthusiasts that were also being realists. Since all of them were involved, in one or the other way, in the trading of pictures.

The study of Wilhelm von Kaulbach (unknown date) (picture: goethezeitportal.de)

The study of Giuseppe Molteni and Massimo d’Azeglio in 1835 (watercolor by Francesco Gonin)

(picture: atlantedellarteitaliana.it)

Karl Eduard von Liphart in his study (or »Zauberhöhle«, as the Morellians used to say;

compare GM to Jean Paul Richter, 10 January 1888) in Via Romana, Florence

(after painting by Ernst von Liphart) (source: Käss 1987, picture No. 24 after p. 299)

The study of Hans Makart (inspiring also the Roman salon of Donna Laura Minghetti)

The study of Franz von Lenbach (picture: tumblr.com)

INTERIORS OF CONNOISSEURSHIP: A VISUAL HISTORY

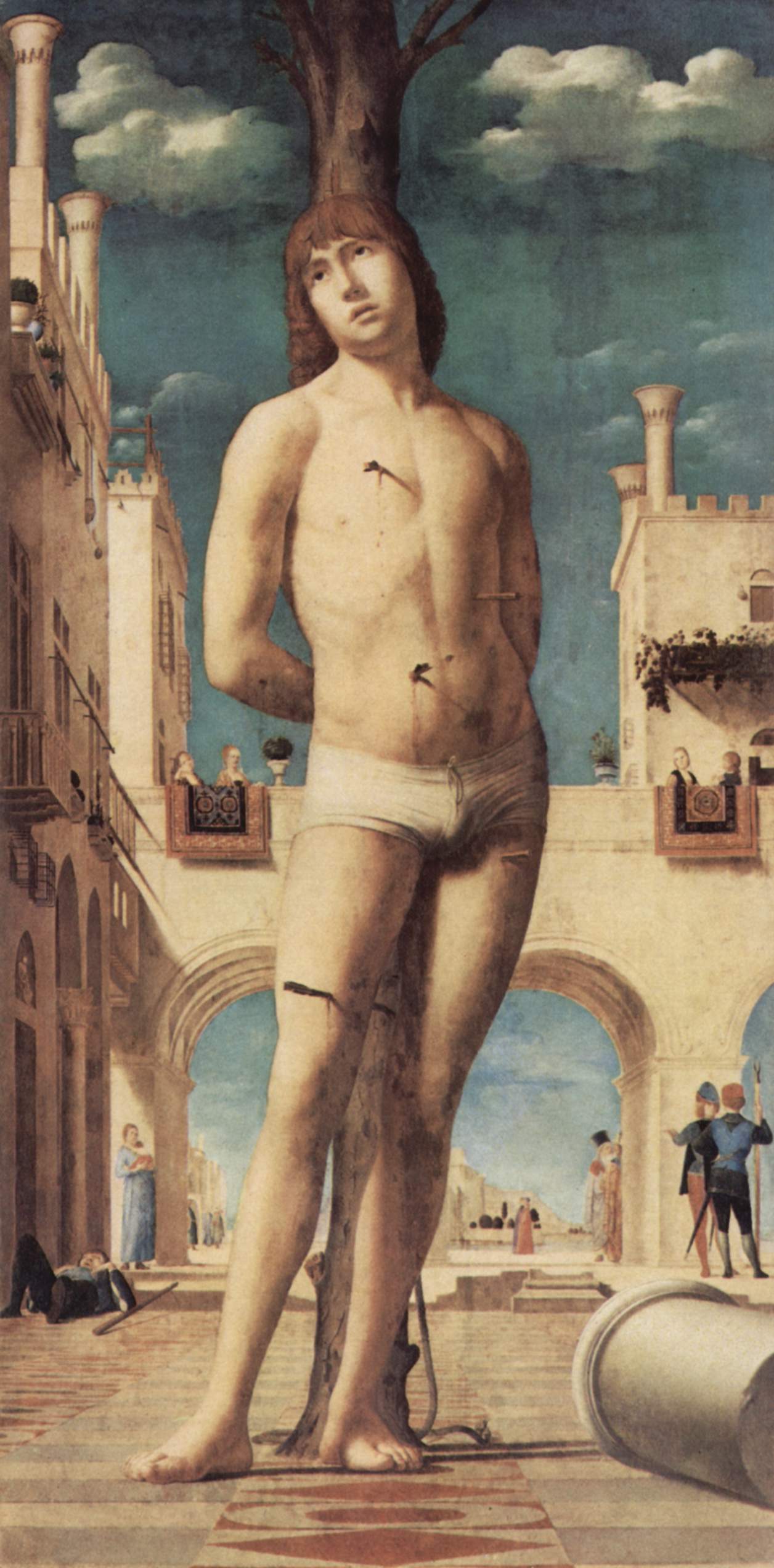

»Ueberschritt man den lichten geräumigen Hof und erstieg die zwei hohen Stiegen, so befand man sich in der nicht grossen, aber behaglichen Wohnung, deren beide Zimmerreihen, die eine nach dem Hofe zu, die andere nach dem geräumigen Garten hin gelegen, vortrefflich erhellt und daher zur Aufnahme von Bildern besonders geeignet waren. An den Wänden des Corridors hingen die zahlreichen Zeichnungen, die Morelli gesammelt. Unter den Gemälden aber waren seine Lieblingsmeister vertreten, Sodoma durch eine frühe Madonna, Moretto durch das kleine feine Bild Christi mit der Samariterin, Viti durch die hl. Margarita, Giovanni Bellini durch eine Madonna von noch mantegnesker Herbigkeit. Dazwischen ein paar Thonmodelle, von Jacopo della Quercia das Relief einer Madonna, von Benedetto de Majano ein knieender Engel [see below]. Das Speisezimmer war mit einer Anzahl auserwählter Bildnisse von Basaiti (datirt 1521), Romanino, Moroni, Pontormo (der junge Bandinelli) geziert, woran sich in den anstossenden, dem Quattrocento gewidmeten Räumen das Bildniss [sic] Lionello’s d’Este von Pisanello sowie das des Giuliano de’ Medici von Botticelli schlossen. Die Mailänder Schule war durch eine schöne Heiligenfigur Borgognone’s, eine reizende kleine Madonna von Luini, den segnenden Christusknaben Boltraffio’s und ein Jünglingsportrait Ambrogio de’ Predi’s vertreten; die Veroneser stellten ihre Buonsignori und Caroto (beides Predellen), ihre Giolfino, Frac. Morone und Gir. dai Libri; die übrigen Oberitaliener Defendente Ferrari, Bartolommeo Montagna (Hieronymus), Civerchio, Sophonisba Anguissola (hl. Familie von 1559). Weiterhin sind zu erwähnen die Florentiner Botticelli, ausser dem genannten Bildniss [sic], mit der Geschichte der Virginia und einem segnenden Christus, Pesellino, Bacchiacca (Kain und Abel), unter dem Namen Baldovinetti ein Kopf in Fresco, aus Verrocchio’s Atelier ein kleiner Tobias mit dem Engel; endlich die Sienesen Matteo di Giovanni, Neroccio und Balduccio (Clölia) und die Ferraresen Ercole Grandi und Atichele Coltellini (Darstellung im Tempel). Im Arbeitszimmer aber hingen, um das Auge durch den Anblick einer ganz verschiedenen Kunstweise frisch zu erhalten, nur Niederländer und zwar durchaus mit feinem Geschmack ausgewählte, wie die Namen Maes, B. Fabritius, Flinck, Backer, Molenaer, A. Palamedes, Jobst Berck-Heyde beweisen.«

(Source: Seidlitz 1891, p. 349f.; the only lengthy description of Giovanni Morelli’s Milan flat in 14, Via Pontaccio (that he took in 1874), of which we do dispose of; but compare also Münz 1898, p. 100 for Morelli’s not being interested in worldly splendours)

(Picture: lombardibeniculturali.it; Benedetto da Maiano)

(Picture: Stefano Stabile)

Morelli was very committed to the (already existing) idea

of a museum of Lombardic sculpture in the Pinacoteca di Brera

(see GM to Francesco De Sanctis, 18 September 1862

(Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 38f.)),

which was realized, in 1862, as the Museo di Arte Antica

(and later moved to the Castello Sforzesco).

*

PICTURES TRAVELLING

Testa d’angelo by Vicino da Ferrara,

and from Morelli’s own collection

(picture: lombardiabeniculturali.it)

Giovanni Morelli did not display ambiguity if writing to his friend and mentor Otto Mündler. On the contrary: he did write to Mündler very frankly, telling him about his joys as well as about his financial problems (and also due to these problems and due to a deteriorating financial situation he did actually write).

But nonetheless: in the letters to Mündler does show to what degree of ambiguity Morelli was capable. Or better: if the letters to Mündler are read in context, it does show that Morelli had developed to be a master of ambiguity. Which does also mean: a virtuoso in at times showing what, at another time, he was hiding.

This had a playful side to it that shows for example in one significant detail: since only if referring to Mündler Morelli used the notion of ›Bilderspekulant‹ in an affectionate way.(21) That is: in a positive, and playfully cheerful way, since he was referring to a dear friend.

While speculants on the other hand, particularly speculants in the picture market (and particularly Jewish speculants), were, as said above,(22) anathema to him. Although, to some degree, he had become such speculant himself.

Morelli’s letters to Mündler also show that there was a need to explain a need of money.(23) Since, during the 1850s, Mündler had known Morelli not as someone in need of money. His actual turn to picture connoisseurship had occured while Morelli had still been a modestly well-to-do squire, living on a probably modest size manor, beside that his actual home was still Bergamo.

But Mündler, during the 1860s, was now to hear a constant refrain,(24) declaring a need of money. And at one occasion explaining also a need of money, that had developed into an actual economic crisis.

And only this one time Morelli did reveal that his financial problems were directly linked with the situation of the Lombardic silk industries. Because only here, in the letters to Mündler, he did link his own financial situation with something as specific as the ›cocoon harvest‹.(25)

He still lived, with his mother, on the income they had on property. But since this income had drastically diminished, they were in need of money. And Mündler was the one agent who was able, if he was capable to sell pictures Morelli provided, to help.

One may only imagine that this situation Morelli would never have been able to explain to Genelli. To Genelli who had regarded Morelli as the poet-to-be, had heard his mourning about having to care about ›disgusting‹ economic matters, and Genelli had known Morelli as his dear and nobly-minded friend who had helped him, Genelli, repeatedly out of trouble, because Morelli had known to find buyers for Genelli’s works.

Thus it is very likely that Morelli actually hated having become more and more deeply involved, without him actually wanting to, in the picture market (and collaborating with Mündler only at first), while this, his letters to Mündler do show as little, as his letters to Genelli had remained completely silent as to all associated with buying and selling. And the correspondence with Genelli had, maybe in consequence, come to an end at the very point Morelli was no longer a mere collector but, in some way, a speculant, speculating on good prices for pictures he had found and identified, and informed Mündler about such pictures. Pictures to be sold. Abroad.

POPULAR WISDOM AS TO AMBIGUITY

›…lighting one little candle for the devil today, and tomorrow one for the Madonna‹

·····················································································

»…heute dem Teufel ein Kerzchen anzünden und morgen eines der Madonna«

(GM to Jean Paul Richter, 10 October 1889: »Es ist aber das Charakteristische

dieser laienhaften Kunstkritiker [Cavalcaselle and Bode], dass sie,

um unparteiisch zu erscheinen, heute dem Teufel ein Kerzchen anzünden

und morgen eines der Madonna.«)

One might take the view that the exporting of a minor picture, resulting with that picture being kept in a foreign museum, and, in some sort, being kept better than anywhere else in the world, might be seen as a patriotic act. As a patriotic act as, for example, preventing a major work of art from being exported (to whatever museum). Or at least: as an act not lacking, to some degree, patriotism, because also exporting a picture could be interpreted as a contribution to protect the cultural heritage of one’s own home country.

And if we see the connoisseurs, museum officials, and (to some degree) politicians of the 19th century debating these issues, the debating goes on, naturally, if the history of 19th century connoisseurship is being written.(26) We face situations »fraught with ambiguousness and double-dealing«,(27) and we see Giovanni Morelli, literally: in the middle of this ambiguity.

But nonetheless, with Morelli it is rather easy. Which means: it makes little sense to defend him, again and again, in interpreting his helping to sell, or actual selling of pictures to foreign museum as patriotic acts (or at least as acts not completely lacking patriotism) – because this was not how Morelli felt himself. At least this was not all Morelli felt.

Of course he showed able to interpret his own acting from various sides and viewpoints, but it is one of the very likable sides of Morelli: whatever he might have done, and however he might have interpreted his own acts – his bad conscience showed, and that was that.(28) In other words and again: it makes little sense to defend all of his acts as patriotic or as only being patriotic acts, because this was not how he felt himself, displaying at least mixed feelings. Due to a debating with himseslf (which again, makes him very likable, because if there was a thing that he was lacking, this one thing was cynicism; and if there was a thing that he could not do at all, it was simply being cynical. That is: completely cynical and also: remaining cool, dispassionate. Since a dispassionate Morelli simply did not exist at all (and rather is to be regarded as a classic oxymoron).

TRAVELLERS IN CONNOISSEURSHIP

(Picture: doullbooks.com)

While Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle had spent much time in England, indeed had lived in England as an exiled Italian, Giovanni Morelli was to visit England for the very first time in 1868, at a time Cavalcaselle, in cooperation with Joseph Archer Crowe, already had been publishing epoch-making books on the history of Italian painting (and soon was going to publish even more).

This visit in 1868,(29) the year after he year Morelli’s mother had died, was a somewhat delayed visit, as much of the actual visual apprenticeship of Giovanni Morelli – as a connoisseur of art – was a somewhat delayed apprenticeship; and we are becoming aware how difficult, indeed, it is to actually compare Cavalcaselle and Morelli as two connoisseurs of art, because we are becoming aware here, once more, of the differences between these two men.

Differences beside the more trivial fact that what they had seen, as far as Italian art was concerned, was very different. Morelli, in a word, had no direct knowledge at all of English collections – while Cavalcaselle, this being a perk of his having been exiled, indeed had.

And in that Cavalcaselle had been also a painter, he had, in a way, and at least in this respect, more in common with first-ranking a connoisseur as Charles Lock Eastlake (who had died in 1865), also a painter, had been.(30)

John Ruskin in 1870

English literature of the 19th century does know, for example by Wilkie Collins’ novel The Woman in White of 1859/60, the figure of the exiled Italian, living in England, and teaching, for example, the Italian language.(31)

And Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, a supporter of Giuseppe Mazzini, had been exiled, and had lived like one of these literary characters, whose (revolutionary) past remained rather surrounded by mystery.

While Giovanni Morelli, who also had joined the First Italian War of Independance (as well as the Third of 1866), most deeply hated republicanism, had been an ardent supporter of Cavour (while he apparently did not mention Mazzini a single time at all, in all his letters and writings), and had been and was to remain a declared conservative, still considering democracy probably as the least worst of all political systems.(32)

As a son of the possessing classes, it had been possible for him to acquire a sterling education (that Cavalcaselle certainly to some point was lacking); and one of Morelli’s preferred writers was for example Laurence Sterne (whose mind he did, perhaps a little surprising, compare with that of Italian painter Correggio;(33) but in fact this is just another example of the – often forgotten or completely having remained unknown – Morelli, who did see the visual arts against a backdrop of literature and literary education, closely related with his general interest in human nature and the observing of human behaviour and social life, and now also, or: all the more also, since ever he indeed had turned to connoisseurship, vice versa).

Morelli did take, on rare occasions, notice also of John Ruskin,(34) but showed little interest in this teacher of how to look; and it does seem that Morelli actually showed more interest in a poet like Robert Browning than in Ruskin.(35)

Laurence Sterne (1713-1768) by Sir Joshua Reynolds

Morelli was to see England again only in 1882, and for a third time in 1887.(36) In 1868 he was an elected member of the Italian parliament with English friends; in 1882 he had become a senator and he had also become a friend of the Prussian Crown Princess (the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria), and his first book was about to appear in the English language. In 1887 he was to be presented even to the queen herself (see chapter Visual Apprenticeship III).

This was to be the future biography of a son, whose mother had died in 1867. And certainly in 1868, when travelling to England via Belgium and the Netherlands, Morelli was still in mourning. And only years after, when speaking to his pupil about the 1868 trip, he was to refer to this trip waggishly in terms of visiting various collections accompanied by charming women (which was his way of explaining or excusing that he had not seen everything, and what he had seen, not with full concentration).(37)

While he had been looking, in around 1867, at his own situation in life, musing also about what he still was capable to do in life (while the seeing of picture, here, certainly meant and was welcome as a distraction). His bosom friend Antinori who had married in 1853 was now widowed, and heard Morelli reflecting about marriage.(38)

A classic friendship like Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson?

Giovanni Morelli and Gustavo Frizzoni at Milan (source: Bora (ed.) 1994, p. 91)

Gustavo Frizzoni (1840-1919)

(source: Anderson 1996, p. 115)

Genelli had heard, younger Morelli, once joking about him, that is: his skull not displaying an ›Ehestandshöcker‹,(39) by which Morelli had made fun of phrenology, a branch of pseudo-science regarding the shape of a skull as indicative as to a person’s character and nature. But after the death of his mother, who had been ›the family‹ to him, Morelli found himself indeed being alone.

Giovanni Morelli, as said, was never to marry in his life, but in some sense he acted like a father. Because at least in some sense he had adopted and cared, like a father, for Gustavo Frizzoni, the son of his friend Giovanni Frizzoni, who had died in 1849. And Gustavo, who had graduated in 1864, Morelli was to consider as his dear pupil, as his first pupil, in 1870.(40)

He was to travel with Gustavo Frizzoni, and he was, later, to live with Frizzoni, who also was to rent an apartment in 14, Via Pontaccio of Milan.

And with this development we do see the grain of a future development: Giovanni Morelli was to become a teacher, who was teaching, not only to Gustavo, but to a small number of dedicated followers, how to see.

Although one should mention also, and also here, that Giovanni Morelli certainly showed as a passionate teacher at times, but all in all not as an altogether happy teacher. Since as to his teaching success with Gustavo Frizzoni he was to use very critical words.(41) And if ever he was to consider one of his followers (we exclude Benard Berenson here) as a first ranking connoisseur of art at all is very questionable (compare also chapter Visual Apprenticeship III).

But besides a teaching success, teaching meant also an opportuniy of learning. For the teacher himself. Who was observing how a pupil responded to his teachings, and thus could see art (or even the world) with the eyes of that pupil (like a father might learn to see the world with the eyes of his child again).

With the apperance of Gustavo Frizzoni near his father-like friend Giovanni Morelli, thus, much did change. Morelli chose (or accepted) to live amidst a circle of friends and followers for the rest of his life. This circle, over time, enlarged, until that circle stretched as far as: England. And in 1882 and 1887 Morelli was to return to England. And significantly: It was, then, a Morelli with his entourage of followers and friends. Visiting England, and in some sense: conquering England, in terms of spreading Morellian connoisseurship.

**

TWO) ILLUSIONS, CERTAINTIES AND CERTAIN CONVICTIONS OR: WORLD FAIR OF CONNOISSEURSHIP – THE »HOLBEIN-STREIT«

MORELLIAN MIMICKRY OR: GIOVANNI MORELLI AT DRESDEN

Torn between the wish to contemplate and to enjoy art and also the desire to study as much as possible, Morelli appears to have been at Dresden in 1871, but also on many other occasion in the years to come.(42)

These two rhythms, the pensive, meditative delving into worlds of art and particularly of pictures, and the comparative studies that meant also the constant walking or running from picture to picture, the constant worrying about getting as much reproductions as possible, were hardly being compatible.

At least rhetorically Morelli was capable to give a consistent picture, when writing letters from Dresden, enthusiastic letters on the one hand, but also letters suggesting how much he did work.

And to picture how much he was working, he apparently drew also, once more, on the novelesque sceneries of Alessandro Manzoni. Because the Morelli we see at Dresden was not only contemplating pictures in the gallery of Dresden, and not only strolling about the Brühlsche Terasse – he was also, as he, as waggishly as ever, did suggest – working like a bravo.(43) Like one of the 17th century henchmen, belonging to the militia of Spanish-Lombardic noblemen – and as if he was a bravo, Morelli, at Dresden wanted to make a good job.

But since Morelli’s handwriting does not always show very easy to read, we actually don’t know for sure, if the motif of the bravo was indeed on Morelli’s mind when writing from Dresden. And it might be that he actually did write bracco instead of ›bravo«, referring to himself working like a hunting dog in the Dresden gallery.(44)

But the motif of the bravo might be called as equally fitting, and even if a bravo named Morelli had to be called a philological illusion – crucial insights, gathered by Morelli at Dresden in 1871, certainly had much to do with people having illusions. With individual people sharing illusions of others and thus harboring illusions, or with the social phenomenon of collective illusions as such.

And if the German Kunstforschung (by which we refer to the meeting of connoisseurs, curators, artists, laymen and academics) was just right now, in 1871, debunking myths or collective illusions of the then-art-world, illusions concerning the Dresden version of a Madonna picture attributed in both versions to Hans Holbein, the German Kunstforschung was stimulating, even impelling also Giovanni Morelli, apprentice connoisseur of art and visitor at Dresden, to ponder about collective illusions and the bearing of such illusions as to a history of seeing.(45)

Morelli might have done a good job at Dresden in many ways, but he certainly did make a good job in terms of learning, listening and observing.

As the silent observer, the parade role of his life, he learned from the German Kunstforschung, and from its debunking of myths. And if Morelli already had learned from many antecedents in connoisseurship, one might say that, now, he was learning from contemporary state-of-the-art connoisseurship. After learning from the ancients, he now learned – and borrowed insights, or found some thoughts of his own (that resulted from synthesizing of his antecendent’s thoughts) confirmed by the contemporaries. And one might say that now he did learn horizontally, instead of going back, to the sources, in vertical direction.

»In unserem Falle aber [if the above picture, the Dresden version, was by Holbein] müsste Holbein ein vollständig

Anderer geworden sein, als er war; er müsste sich nicht nur absichtlich seiner technischen Methode,

vor Allem seiner Impastirung, sondern auch eines grossen Theils seines Könnens begeben, seine

Geschicklichkeit und Sicherheit der Handführung verläugnet, alle die kleinen, unnachahmlichen Vortheile

und Eigenthümlichkeiten seiner Technik verheimlicht und durch schwerfälligere oder weitschweifigere

ersetzt haben. Ja, er müsste mit einem, seiner Erfahrung fremden und ungewohnten, Bindemittel,

zum Theil mit Farben, deren chemische Beschaffenheit ihm noch unbekannt, und zuletzt sogar nach einem

coloristischen Princip gearbeitet haben, welches diesseits der Alpen erst ein halbes Jahrhundert später

herrschend wird.« (Bayersdorfer 1872, p. 25)

It was as smart and sensitive a man as German connoisseur of art Adolph Bayersdorfer (1842-1901) who did, as concisely as one may only think, sum up the findings of the German Kunstforschung in 1871.(46)

Which also means that Bayersdorfer penned down already in 1871 what was to be published in 1872 as the argument behind the 1871 declaration of the German Kunstforschung concerning the Madonna question.

But since this brochure is nor very well known, nor has, apparently, ever been translated, it is hardly known at all, how much Morelli, as the connoisseur of art that the art historical tradition does know of, does seem to owe to Bayersdorfer and to the collective of the German Kunstforschung, and this not only as to the more general findings concerning the two paintings as such, but also – seemingly – as to style, basic vocabulary, stance and even as to a general philosophy behind scientific proceeding in connoisseurial affairs.

It is no less than another myth, another illusion that has to be debunked here: if Morelli is to be called a representative of scientific connoisseurship, he is certainly not to be called the only representive.

And even less he is to be called the inventor, or the only inventor of scientific connoisseurship.

Since if such a title might also be given to just one man, such title might also be given to Adolph Bayersdorfer, the voice of German connoisseurship, whose brochure could also be called the actual paradigm of crystally clear scientific reasoning in matters of attribution and authentication, arguing as concise and transparent as one may only think of. And an academic art historian Adolph Bayersdorfer was not, but: simply a connoisseur, and later a man of the museum.

But someone who was able to develop his opinions most concisely and transparent. Especially if we do think of writings by Morelli, in their typical mix of self-expression and dissimulation (of doubts or of actually very relevant and materially important insights, clues and reasons). Writings that seem to be full of actual references to Bayersdorfer, but given the actual prevailing view of seeing in Morelli the main representative of scientific connoisseurship, the mainstream view might rather, but questionably, be inclined to assume the German Kunstforschung being influenced by Morelli and not the other way round.

It is a sort of protective borrowing that connoisseur of art Giovanni Morelli seems to have practiced throughout his life: he did indeed learn fast and was capable to fuse influences that were coming from all sides. But less distinct was on the other hand his will to acknowledge such thing as influence, and particularly if such influence he was borrowing from German connoisseurship.

And friends of Morelli were indeed to think that Morelli himself, in person, had solved the mystery of the two versions of the Madonna of Bürgermeister Meyer.(47) But far from that: What Morelli did practice at Dresden in 1871 was learning and observing and, above all: comparing. Because the least one might say is that, in Morelli’s books, one does find assonances of what the German Kunstforschung was able to unfold on occasion of the »Holbein-Streit«.

Morelli regarded, as the apprentice that he was, the Dresden version, at first, as being as well an original, and as the Darmstadt version of the Madonna. And this was exactly the one collective illusion that he did share, and that connoisseurship, operating scientifically, but not with Morelli being visibly or audibly present, did debunk in 1871. Credit has to be given to the German Kunstforschung, whose voice turned out to be Adolph Bayersdorfer (whom Morelli was also to attack later in life due to an alleged ›assault on Leonardo).(48)

Although Bayersdorfer showed a proclivity for speaking in terms of painterly technique,

he does also relate artistic expression, less but also in terms of form, with the mind

of the artist, using yet, in 1871/72, the term ›unbewusst‹:

»Wie in der Conception im Grossen, so spiegelt sich auch in der technischen

Behandlung im Kleinen und Kleinsten die besondere Natur des Künstlers wider

und zeigt uns unter dem Scheine der blossen mechanischen Handtirung den

unbewussten Zwang einer besonderen, von einem intelligenten Willenscentrum

ausgehenden Naturbetrachtung. Man hat also in der Technik eines Künstlers nicht

eine zufällige, imitirbare Formalistik und rein äusserliche Gewohnheit zu erblicken,

sondern ein continuirliches Informtreten geistiger Vorgänge. Sie entstehen aus dem

Bestreben, die Darstellung künstlerisch zu verdeutlichen und mit Leben zu begaben,

vom ersten Entwurfe angefangen bis herab zur vollendeten Lasur. Die feinsten,

complicirtesten, oft unbewussten Regungen der Künstlerseele, wie sie im Contact

mit Gegenstand und Material entstehen, werden in der Technik reflectirt.

Im flüchtigsten wie im intimsten Vortrage drückt sich demnach ein Lebensgehalt aus,

der von der einen individuellen Künstlernatur bedingt und beherrscht ist, uns dieselbe

scharf begränzen hilft und das beste Erkenntnismittel für dieselbe bleibt«

(Bayersdorfer 1872, p. 18; for »Eigenthümlichkeiten der Formgebung« see p. 19)

And from Dresden and from the »Holbein-Congress«, the world fair of state-of-the-art connoisseurship, Morelli might have taken various insights with him, when, in 1872, he was to travel to Spain: First the insight that much spread and shared illusions do exist also in connoisseurship (since a consensus, shared by many people, like the consensus to see in the Dresden version a picture by Holbein, might turn out to be a mere myth, an illusion, a lie).

A second insight might have been the result of becoming aware that he himself, although having dedicated long years now to art studies, at first had showed to be inclined to harbour an illusion.

A third insight might have been a renewed insight into the state of German education or here: art historical Bildung (for example and particularly as to the historical use of color). A fourth into the standard practices of German connoisseurs, if discussing originality (drawing also on observations as to the use of color), a fifth, perhaps a clue as to the intelligence and cleverness and idealism of connoisseur of art Adolph Bayersdorfer.

And if Morelli was to attack Bayersdorfer many years later, at the end of the 1880s, this attacking, with much sympathy for Morelli, might be called also a way of showing one’s respect to Bayersdorfer.

Who certainly did precede Morelli in putting into words what scientific connoisseurship could be and on what general thoughts it might be based on. And did put into words also a reasoning on form, very similar to that Giovanni Morelli was to become famous for (compare the Bayersdorfer quotes above).

If Morelli did borrow also from Bayersdorfer, he did certainly not acknowledge the fact (and even less than he did acknowledge his borrowing from his antecendents).(49)

But it might also be that Bayersdorfer put into words what the world of connoisseurship, and with it also Giovanni Morelli, tended to regard as desirable steps towards a more reflected dealing with questions of authorship and authenticity. Which is why we do speak only of assonances, concerning seeming echoes of Bayersdorfer in Morelli.

But in sum we do see a Morelli learning fast (and not teaching, or even joining a debate) at Dresden, and we do see Morelli elaborating subsequently vocabulary and basic thoughts that one may also find, with some nuances differing, in Bayersdorfer.

But one might see also individuals, and not only two more or lest high-profile individuals, developing, in close interaction, closely related styles of reasoning and of expressing basic thoughts. And it does, in the end, not really matter, if there was only one inventor of scientific connoisseurship. Since it could also be that there were many representatives of scientific connoisseurship. But only one, wearing a Russian half-mask, indeed and in the following, embarked on the mission of being an actual advocate of and for scientific connoisseurship, and this was to be certainly Morelli, and only Morelli.

Because this, Bayersdorfer, except of giving a voice to the findings as to Holbein, never regarded to be his mission. And also due to his writing and publishing only little, Bayersdorfer, who was one of the first German connoisseurs to acknowledge generously Giovanni Morelli’s skills, was to remain rather unknown.(50)

But Morelli certainly did know him. He perhaps knew him at Dresden in 1871, but certainly at Vienna in 1873.(51) And he, the author Giovanni Morelli, probably also knew Bayersdorfer’s writings, that is: his brochure of 1872, rather well.(52) Since Giovanni Morelli’s writings, as we show here with quotations from Bayersdorfer, are perhaps not very musical prose, but full of seeming echoes they are, or better: full of assonances.

*

TO FINALLY SEE SPAIN, THE REAL SPAIN

(Source: Anderson/Morelli 1991a, p. 115)

It had been a waggish gesture in 1839, when Giovanni Morelli, in cooperation with professor Engelhardt from Erlangen, had addressed Genelli. In writing – in a supplement to the widely read Allgemeine Zeitung – on drawings by Genelli.(53)

Because they had written in disguise, signing only as ›ein Dilettant‹.

But as a dilettante that seem to know something that one was only being able to know if informed directly by an artist.

This was perpetrator’s knowledge, as it were, if one did inform the art loving audience that Genelli had pictured Don Quixote in a very specific moment: namely when Don Quixote was reflecting about the exploits of his predecessor Amadis (see text below).

And if Genelli had read this article, and if he had read on – he probably, unfortunately, had not seen the article at all –,(54) if the artist had read on, at some point, he would have become aware who actually was writing, at least: who had also contributed to this article, this one longer description of a work of art, and to the appearing of this article in print.

Because the long description and interpretation of Genelli’s ›colossal‹ head of Don Quixote is the one longer description and interpretation of a work of art (and particularly also of eyes, and a gaze), written by, or mainly by Giovanni Morelli, that we do dispose of.(55) By Morelli who, as Genelli of course did know, or would have known, was the actual owner of this large drawing, having been dedicated to him by the artist.(56) And the anonymous dilettante who had written this article, pretending to be an anonymous dilettante, was contemplating, as he also did write, making it obvious with a waggish gesture, that he was contemplating, probably in standing, the magnificent drawing that was presently leaning on his couch.

(Picture: literanda.com)

Don Quixote does represent here and in our context, the imaginary Spain that, as Morelli did once write to Otto Mündler, was so dear to his imagination.(57)

This was the Spain that one could get to know by reading Spanish literature, Cervantes and Calderón, the two Spanish writers, above all, also having been so dear to the German romantic writers, and this was probably one impact that the Romantik indeed had had on Giovanni Morelli: to inspire him to delve into this imaginary Spain. Of Cervantes and also of Calderón, with Morelli, here, as he actually rather often did, to desist from his own preconceptions.

Because he was a most enthusiastic reader of Catholic plays, as Catholic as was the world of Calderón.

But maybe Morelli was someone very aware of the differences between reality, appearance and illusion from early on, since his early interest in drama, comedy, in the world of the stage, might also haved sensitized him to the complicated relations between various layers of reality.

And also Don Quixote, very in particular, might have had this effect on him, since the before mentioned (and below quoted) ekphrasis does aim at interpreting Don Quixote as being torn between his inner vocation and ambition to surpass the exploits of Amadis, and his lacking ability to do so.

Genelli did picture Don Quixote at the very moment when realizing that this might be impossible, not due to the lack of will, but due to his lack of being able so, realizing also that there was nothing, the plain nothing that he had to face, if this one guiding and shining idea did faint.